Concepts of Efficiency

The everyday concept of efficiency is fairly straightforward. It connotes an optimizing relation of gains to losses, as well as the avoidance of wastage. Within economics, more technical notions of efficiency include Pareto efficiency and potential Pareto efficiency. These are central notions for cost-benefit analysis (CBA), which seeks to identify efficiencies across multiple policy domains. CBA converts each policy domain’s benefits into monetary equivalents and assumes that maximizing overall monetized benefits is a worthy goal (even if not the only worthy goal). By contrast, domain-specific analyses seek locally efficient policies and often employ the notion of cost-efficiency or cost-effectiveness. Within health policy, for example, cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) seeks to identify policies that would maximize certain health-related outcomes given a fixed budget. Here, there is no need to convert relevant outcomes to monetary equivalents because there is no need to express both health and nonhealth benefits in terms of some common unit.

This article’s discussion on efficiency will focus on the notion of cost-effectiveness as it is employed within health policy. Two issues in particular are addressed: first, because the idea of cost-effectiveness suggests the importance of maximizing something, some specific health-related benefit(s) must be identified as the maximand at the individual level; and second, after an individual-level maximand is determined, many philosophical and ethical considerations bear on the selection and interpretation of the social maximand that will ultimately inform policymaking at the population level. These two issues are explored in the Sections Individual-Level Maximands and Social Maximands and the Ethics of Maximization, respectively.

Individual-Level Maximands

Health

It is natural to think that efficiency in health policy should be construed as maximizing health itself. However, two related reasons have been put forward against that proposal. First, it can be difficult to make the assessments of overall health that it requires. Second, asking if someone is in ‘good health’ is often a way of asking if their health adversely affects their life. If health’s impact depends on the way it interacts with other features of one’s situation, then it may be misguided to focus on health itself rather than on the ways health, together with other factors, affects people’s lives.

Some have replied to these and similar worries about focusing on health itself by noting that it is clearly possible to make at least some relevant comparisons, such as when it is said that someone with a mild sore throat is healthier (assuming all else is equal) than someone who cannot walk. This judgment is a plausible assessment of health itself, not a judgment about health states’ impact on the goodness or badness of a life. But is it possible to build a rigorous assessment of population health around specific health-focused judgments? Doing so would require a large number of health state assessments, but many such judgments are not as clearcut as the example just offered. To illustrate the difficulty, Daniel Hausman presents the example of a person with a mild learning disability and someone with quadriplegia. Although the first person is presumably in better health than the second, Hausman doubts that there is an objectively defensible framework for comparing units of mobility with units of cognitive functioning. This, he argues, highlights the difference between saying the first person literally has more health (a descriptive judgment) and saying that it is better to be in his health state than to suffer from quadriplegia (an evaluative judgment). Given the conceptual difficulties with measuring a population’s literal health (especially when health is multidimensional), and given that health policy’s main interest is in how good a population’s health is or can be, it is reasonable to conclude that the maximand at the individual level should be evaluative, rather than descriptive. This in effect would bypass the need to measure health itself, but it also raises new questions about how health should be valued.

Well-Being

If one seeks to evaluate the goodness or badness of a health state, a natural proposal is to focus on the impact the state has on individual well-being. Of course, much would turn on the nature of well-being, and philosophers have identified important problems for several accounts of it.

One central candidate is subjective well-being, i.e., the sense of satisfaction with one’s life and prospects. A central worry with this approach is that it could ignore significant health improvements that accrue to those who already enjoy high subjective well-being. Ronald Dworkin used the example of Dickens’ Tiny Tim to make a similar point. If the magnitudes of relevant health benefits are tied to improvements in subjective well-being, then an intervention that restores Tiny Tim’s mobility may bring very little health benefit, given Tim’s already cheerful disposition. A similar problem concerns adaptive and even malformed preferences: intuitively significant improvements in health will be downplayed if they would go to individuals who are already subjectively satisfied with very little because of exposure to aspiration-numbing deprivation or injustice.

Preferences Satisfaction

Economists often equate well-being with the satisfaction of preferences, and many assessments of health policy draw on valuations derived from data about respondents’ preferences over health states. ‘Satisfaction’ can be a misleading term here, because what is relevant is getting what one wants, not a subjective feeling that may (or may not) come from getting what one wants.

There is strong reason to keep individual well-being and preferences satisfaction separate, and to avoid tying the importance of health improvements to individual preferences. For example, one may prefer a policy in part for altruistic reasons, i.e., because of its impact on third parties. In such cases, satisfying one’s preferences could actually come at a cost to one’s own well-being. Second, it is possible for individuals self-interestedly to want and prefer things that are not in fact good for them, that do not in fact promote their well-being. This can be due both to false empirical beliefs and to misguided prudential outlooks. Prudential preferences are hardly ever brute ‘gut’ preferences. As TM Scanlon put it, ‘‘My preferences are not the source of reasons but reflect conclusions based on reasons of other kinds’’ (Scanlon, 2003, p. 177). This opens the possibility that individuals’ preferences may be insensitive to objective reasons for thinking that a given health state is better or worse for them.

Opportunities and Capabilities

Many take examples like the one involving Tiny Tim to justify focusing on more objective consequences of deficits in health. Regardless of its impact on his subjective welfare, Tiny Tim’s impairment reduces the opportunities that are available to him in significant ways. Amartya Sen has long advocated for a metric of policy evaluation that focuses on people’s objective capabilities. Such a framework would divorce the public importance of health-related capabilities from any given agent’s personal preferences about them: one person in a given health state may be made miserable by it, whereas another in a similar state may have adjusted fully and now lives a flourishing life. From a perspective of opportunity and capability, these individual viewpoints (and their aggregation) may not matter as much as the disinterested assessment of whether the health state generally impedes or closes off life opportunities that society deems it morally important for citizens to have access to. A view of this sort will therefore not base the valuation of population health on individual preferences or subjective well-being, because these capture the state’s importance along the wrong evaluative dimension. The main questions raised by opportunity-based frameworks concern which health-related capabilities should be the focus of health policy, and how they can be measured in a scientifically respectable way. Hausman (2010) has offered the most detailed current proposal, which suggests using deliberative groups to evaluate health states ‘‘with respect to the relation ‘is a more serious limitation on the range of objectives and good lives available to members of the population’’’ (p. 280).

These are the most prominent individual-level maximands on offer, and it is important for health economists to be able to distinguish between them and to keep in mind the reasons for and against them. Consider again economists’ most common maxim and, preferences satisfaction. If the value of a health state is determined by individuals’ (aggregated) preferences about it, then questions arise about whose preferences should count. One natural thought is that relevant preferences should be adequately informed, and this leads to the suggestion that the preferences of those who are most familiar with the health state should count for more. But here the issue of adaptation arises, because it is possible to live an excellent life after adapting to a given health state. If adaptive preferences inform society’s ultimate appraisal of health states, then the importance of having a range of opportunities open to one will be downplayed: At a certain stage in life, what matters from the first-person perspective is that one is able to lead the kind of life one has decided on for oneself; and once one has decided on living a certain kind of life, it is less important that one be able to choose from among options one has already ruled out. Further, from the perspective of a healthy person who views health states P and Q as equally terrible because of how they conflict with his current life plans, an imagined change from P to Q may not seem all that meaningful, even if in objective terms the change would significantly enhance the range of life opportunities open to the average person in P.

Much of the practical relevance of these debates lies in their bearing on how CEA should be carried out. CEA typically uses quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) as the individual-level maximand. QALYs are designed to integrate longevity considerations with quality of life considerations in a way that enables comparisons between health interventions targeting very different dimensions of health. Because they are built by aggregating individual preferences over health states, QALYs should not be viewed as a measure of literal health; they are rather a measure of the value of changes in health, where the value of a change is interpreted as the difference in the values assigned to the two relevant health states. However, just as it is possible to carry out a CEA using a decidedly descriptive maximand (e.g., number of surgical complications averted), it should also be possible to employ CEA’s techniques in the context of different evaluative individual-level maximands. Whatever individual-level maximand is chosen, it remains to be determined how interpersonally comparable benefits and losses to individuals should be combined and valued at the aggregate level in the service of shaping and guiding public policy. Notwithstanding the ethical issues already raised for preferences -based evaluative metrics, the following discussion of aggregate-level ‘social maximands’ will, purely for ease of illustration, be conducted using QALYs as the illustrative individual-level benefit.

Social Maximands and The Ethics of Maximization

The term ‘social maximand’ seems to suggest that health policy should aim, at least in part, to maximize something. And many philosophers criticize CEA precisely because they believe it embodies a single-minded focus on maximizing QALYs (or on whichever individual-level maximand is ultimately chosen). But this appraisal is too quick. For CEA can be put forward as an assessment of efficiency only, rather than a complete decision-making framework. And even if CEA is proposed as a complete decision-making framework, it is possible within CEA to employ a social maximand that ranks policies on the basis of their interpersonally comparable effects on individuals but which also places differential evaluative weight on otherwise similarly sized benefits depending on who receives them. To use the language of welfare economics, different CEAs can thus operate with different social welfare functions as the social maximand, thereby operating with different adjustments to efficiency. This even opens up the possibility of what might be called an equity-sensitive social maximand. One problem with this approach, however, is that efficiency and equity are usefully viewed as distinct concepts, and an equity-sensitive social maximand blurs the distinction between them. Thus, to keep these dimensions of evaluation distinct, this section begins with ethical concerns that arise when CEAs employ an equity-insensitive social maximand – that is, when CEAs recommend the singleminded pursuit of efficiency, and when efficiency is construed simply as QALY-maximization. The section will close by noting a difficult issue that arises if one seeks to incorporate a certain equity consideration into the social maximand.

Few would claim that QALY-maximization is an irrelevant goal. The question is whether and when it should be constrained by other ethical factors. Philosophers have identified four main factors that are neglected by what shall here be called ‘pure’ CEAs, i.e., CEAs that recommend straightforward QALY-maximization.

Aggregation

Pure CEA permits small benefits to lots of people to be summed up to outweigh large benefits to a smaller number of people. For example, a government-sponsored commission in Oregon (US) in 1990 released a draft priority list of health care services that prioritized some oral and dental treatments over life-saving procedures like appendectomy and surgery for ectopic pregnancy. Dollar for scarce dollar, providing appendectomies was not as cost-effective as those nonlife-saving services.

Discrimination Against the Disabled

Suppose that subpopulation A is disabled whereas subpopulation B is not; each subpopulation is the same size and all individuals are otherwise equally healthy. Now suppose an epidemic afflicts both populations and leaves all individuals with a life-threatening illness. Assume also that logistical limitations allow for life-saving treatment to be administered to just one subpopulation; all members of the treated subpopulation will be restored to their preillness condition and if saved each would live the same number of additional years. Pure CEA recommends against choosing the disabled population, because this generates fewer QALYs. Many find this a troubling form of discrimination.

Priority to The Worse Off

Pure CEA cannot explain why one should give priority to the worse off when this intuitively seems required. Suppose the individuals in Group A generate 0.3 QALYs per year and could be brought to produce 0.5 instead. And suppose that equally numerous individuals comprising Group B generate 0.8 QALYs per year and can be brought to full health (1.0). Once again suppose that scarcity or logistics require choosing just one group to assist. Pure CEA recommends flipping a coin, because from the standpoint of the maximizer, adding 0.2 QALYs per year to a person’s life has the same importance regardless of that person’s initial condition. Many find this counterintuitive and believe there is a moral presumption in favor of treating the worse off.

Fair Chances Versus Best Outcomes

Suppose the members of two equally numerous groups, A and B, each currently generate 0.5 QALYs per year. Now suppose that either A can be helped or B can, but not both: members of A can be brought to generate 0.8 QALYs per year, or members of B can be brought to generate 0.95. Pure CEA favors helping B and neglecting A, but many find this problematic. As Frances Kamm puts it, although the members of B can be helped a bit more, it is true both that members of A are capable of gaining the major part of what members of B can gain, and that this major part is what each cares most about – namely, a substantial improvement in health. This way of describing the situation leads some people to support giving equal or perhaps proportional chances to A and B, rather than choosing to only help B.

Each of these stylized scenarios raises equity concerns, but there is no consensus on how to incorporate equity considerations into health-economic analysis. Consider, for example, the problem of aggregation. Employing different variations of Oregon’s methodology and personal valuations of health states from respondents, Ubel et al. found that pure CEA can equate the successful treatment of 10 cases of appendicitis with the successful treatment of between 111 and 1000 cases of mild hand pain. Yet when the same respondents were asked directly how many cases of mild hand pain would be equivalent to 10 cases of appendicitis, 17 of 42 respondents said it would take an infinite number of cases. This finding comports with a common response to Oregon’s draft proposal: Many believe that, morally speaking, no number of capped teeth could equal or outweigh saving a life with an appendectomy. But this raises a puzzle, as virtually no one claims that it is always wrong to give priority to less serious but more numerous needs over more serious but fewer needs. Suppose, for example, one could either prevent 10 000 people from developing paraplegia or one could save one person’s life, but not both. It seems clear that the relative numbers tip the ethical scales toward the 10 000. But note that there are no people among the 10 000 who, if not helped, could reasonably complain that they were left without mobility while someone else’s life was saved. In that respect, this case parallels the case involving dental services and appendectomy: There are not people among candidates for tooth capping who could reasonably complain that their tooth will be left uncapped if the legislature pays for appendectomies instead. But then if it can still be permissible to favor large numbers in the case involving paraplegia, why not also in the case involving tooth capping? The difficult question, therefore, is not whether aggregation can be morally permissible, but rather when and on what basis aggregation is permissible.

Partially in response to the equity concerns connected to the problem of aggregation, health economists have explored ways to build respondents’ direct rationing preferences into an ‘impure,’ equity-sensitive CEA framework. Such preferences can be elicited using the so-called ‘personal trade-off’ (PTO) exercises of the sort Ubel et al. used to uncover the discrepancy between pure CEA and respondents’ direct rationing judgments. One notorious problem with the PTO methodology is the problem of multiplicative intransitivity. The problem is nicely described by Ubel (2000), pp. 168–169:

Imagine a person who thinks that curing one person of condition A is equally beneficial as curing ten people of condition B, and that curing one person of condition B is equally beneficial as curing ten of condition C. To be consistent, this person ought to think that curing 1 person of condition A is equally beneficial as curing 100 people of condition C. However, when we conducted PTO measurements for three such conditions and multiplied the PTO values of the two ‘‘nearer comparisons’’ (such as A vs B and B vs C), we calculated a different value for the relative importance of the ‘‘far comparisons’’ (such as programs A and C) than people told us when they were directly asked to compare these programs [i.e. A and C].

Because no survey can ask respondents directly to compare every possible pair of competing health interventions, health economists seek a solution to the problem of multiplicative transitivity that could license inferences from discrete preferences about ‘nearer comparisons’ (A vs. B, B vs. C,…,Y vs. Z) to preferences about ‘far comparisons’ (A vs. Z). One problem not mentioned in the economics literature is that success in this endeavor would conflict with some of the equity concerns that raised the problem aggregation in the first place. Suppose that a very long chain of near comparisons begins by comparing an appendectomy that saves one person’s life with an intervention that cures some number of cases of paraplegia. Suppose the next comparison on the chain compares the curing of one case of paraplegia with the curing of some number of cases of one paralyzed arm. Now suppose the chain continues down the line until one gets to the near comparison between curing one case of mild tendonitis with curing some number of cases of individuals who suffer very mild headaches once per week. The worry now is that any solution to the problem of multiplicative transitivity would entail that there is some noninfinite number of mild headaches that would be granted priority over curing a case of appendicitis. There is a deep divide in the philosophical literature as to whether a result like this is tolerable or whether it should be avoided at all costs.

In light of these ongoing and potentially intractable philosophical issues, it may be advisable for health economists simply to rank policies with respect to QALY maximization only and then to explicitly leave it to policymakers to decide for themselves whether and when to depart from maximization for equity-related reasons.

The Concept of Health Equity

The most commonly cited definition of health equity is Margaret Whitehead’s (1991, p. 219):

The term ‘inequity’ has a moral and ethical dimension. It refers to differences which are unnecessary and avoidable but, in addition, are also considered unfair and unjust.

This definition leaves open the possibility that some differences in health are neither unfair nor unjust. This seems to be a virtue. It is not clear, however, that a health inequality must be avoidable before it can be counted an inequity. Here is what Whitehead says about this aspect of equity (1991, p. 219):

We will never be able to achieve a situation where everyone in the population has the same type and degree of illness and dies after exactly the same life span. This is not an achievable goal, nor even a desirable one. Thus, that portion of the health differential attributable to natural biological variation can be considered inevitable rather than inequitable.

There are two ideas at work here. First, there is the idea of the desirability of equality: everyone being the same in some respect or respects. But, second, Whitehead also refers to the impossibility of equality, and it is this that seems to motivate the condition that an inequity in health must be an avoidable inequality.

There is a problem with Whitehead’s avoidability condition. To see this, suppose a subset of the population is afflicted by a health impairment that cannot be avoided or resolved medically – perhaps an unalterable genetic defect makes amputation below both knees a necessity for this group. Suppose also that the legislature is considering whether to pay for wheelchairs for those afflicted by the disorder. On Whitehead’s definition, considerations of equity might say nothing about whether the state should provide these assistive devices. This is because wheelchairs arguably cannot eliminate the differences in health caused by the disorder. Whitehead’s definition therefore seems flawed, because it definitionally entails that the provision of assistive devices is not a demand of equity (Wilson, 2011).

If the concept of health equity should not prejudge substantive issues that a theory of health equity is intended to address, it is better to start from a much more modest version of Whitehead’s definition. Thus, health inequities are simply health differences that are unjust, all things considered. The ‘all things considered’ qualification means that if a difference is an inequity, then there exists a moral requirement on the part of (certain) agents or institutions to do something about them. It clearly follows from this definition that some view of justice is required before a health difference can be counted a health inequity. But at least this new definition does not rule out the possibility that unavoidable health differences raise issues of equity, because an unavoidable health difference could still be unjust if it is not compensated for in the right way.

Unfairness and Equality

Whitehead’s ‘necessary and avoidable’ condition is therefore problematic. Recall, however, that Whitehead’s definition included another condition, viz. that an inequity is an inequality that is unfair. It might seem that this unfairness condition adds nothing to the definition, because whatever is unfair is unjust. But whether unfair inequalities are also unjust depends on what unfairness is, how it is related to justice and moral obligation, and whether other considerations can outweigh or displace fairness in the final determination of what is, all things considered, just and unjust.

How does Whitehead’s definition of health equity connect up with the moral value of equality? In the quotation above, she argues that it is neither achievable nor desirable to have everyone in exactly the same health. Setting aside the question of achievability, why would equality not be a desirable goal? Imagine that medical progress has left us with just one disease – heart disease, say – that sets in at the age of 100 years and leaves us dead at 105 years. Would this not be desirable? Surely it would. Imagine a slightly different scenario in which heart disease sets in at the age of 100 years for both men and women, but men tend to die at 105 years whereas women die at 110 years. If one then had to choose between giving males an extra 5 years of life expectancy and giving females an extra 6 years, would not there be something to be said in favor of closing the gap rather than widening it with the more efficient female-focused policy? And might not the value of equality explain why it would be unfair to help the women before helping the men?

These considerations might suggest that equality is indeed intrinsically desirable, so long as its place is known. Having human beings be equal in each and every respect would surely be undesirable, and this may be all Whitehead is saying. But this does not entail that it would be undesirable to promote greater equality of health prospects. In some contexts, equality may be very important, and in others it may simply be less important than some other moral considerations.

Equality of Outcomes Versus Process Equity

This last point is sometimes invoked in the context of sex differences in longevity. In 1994, the World Health Organization’s Global Burden of Disease team used high-income populations in low-mortality countries to peg the biologically determined sex-based inequality in longevity at 2–3 years. It might therefore be suggested that if one is committed to equity in health, health care systems should tilt in favor of treating men, as a way to achieve equality of health. However, Amartya Sen and Angus Deaton distinguish between equality of outcomes and process equity (Sen, 2002, pp. 660–661; Deaton, 2002, p. 24). Process equity is the idea that procedural fairness – for example, in health care access and delivery – is of independent moral importance. In Sen’s and Deaton’s view, process equity can sometimes be more important than equality of outcomes. This line of argument would enable one to give some value to equality of health outcomes without letting it dictate health policies that seem intuitively unjust for other reasons.

There is, however, a response that can be made by someone skeptical of process equity. Indeed, it is a response that Deaton himself has made. He first concedes that the inequality in life expectancy between men and women may justify tilting medical research toward understanding the factors that disproportionately affect men (Deaton, 2011). This is the sort of bias that seems defensible in cases where diseases disproportionately afflict racial minorities. It is, therefore, not clear that it should be ruled out in the context of sex differences in longevity. But if a bias in state-funded research and development can be justified, then why not a bias in health care delivery?

Here Deaton provides an answer that invokes the importance of equality of outcomes, not process equity. He notes that although women have lower prevalence of conditions with high mortality, they have a higher prevalence of conditions with high morbidity. Thus, in some contexts, providing equality of access to health care could actually be one way of equalizing overall health between men and women, because women’s advantage in life expectancy might offset the morbidity disadvantages they face. Indeed, there are surely many health and nonhealth disadvantages faced by women that a few extra years might help (partially) to offset. Thus, perhaps process equity seems to conflict with equality of outcomes only when one is focused on the wrong outcome. For example, if we instead focus on guarantying that a certain range of life opportunities is open to all, there may be no reason at all to eliminate women’s current advantage on the single dimension of longevity.

Questioning The Value Of Equality

So far no reason has been identified to reject a form of egalitarianism that is prominent in the philosophical literature and that nicely explains the connection between Whitehead’s Bibliography: to fairness and the close linguistic relation between equity and equality. The egalitarian philosopher Larry Temkin puts it thus (Temkin, 2003, p. 775):

The essence of the egalitarian’s view is that comparative unfairness is bad, and that if we could do something about life’s unfairness, we have some reason to. Such reasons may be outweighed by other reasons, but they are not…entirely without force.

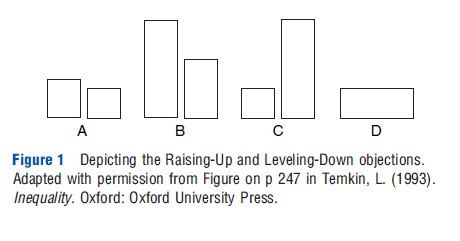

Temkin maintains that unfairness exists when some are worse off than others through no fault of their own. Temkin identifies two objections that might be used to rebut his view that undeserved inequality is intrinsically bad. These are the so-called Raising-Up and Leveling-Down objections (Figure 1).

Consider first the choice between scenarios A and B. There are two social groups in each of A and B. The width of the bars reflects the size of the group’s population, and the height reflects how well-off each individual within a group is. Height may here capture years of life lived, quality-adjusted years of life enjoyed, life expectancy, etc. Taking A as the status quo, one is asked to consider whether an otherwise benign policy should be implemented that would lead to scenario B. The Raising-Up objection to a Temkin-style egalitarianism simply points out that, insofar as one is an egalitarian, one must condemn the move from A to B. The antiegalitarian who makes this objection emphasizes that the move to B makes everybody better off. How, she will ask, could there be any reason not to improve the lives of everybody? (The assumption here is that the improvement is welcomed and not forced on anyone who does not want it.)

Temkin’s response to this objection underscores a point made above, namely, that if equality has value, it does so only in the context of other important values. To use an example of Joseph Raz’s, it is not important that everyone be equal with respect to the number of hairs on their shirts. That sort of egalitarianism is precisely the sort that Whitehead would be right to call undesirable. So where it makes sense to talk about the value of eliminating undeserved differences, there will always be other genuine values that are also relevant. But then if equality is not the only value, it is possible that equality can be outweighed by the other values whose presence makes equality relevant. This is Temkin’s response. He agrees that a move from A to B may be the right choice once all values and reasons are given their due. He simply notes that one consideration, equality, counts against the move. To some, this is a fine response in defense of egalitarianism. True, it may seem strange to deflate equality’s relative importance this much, but that seems necessary if one is attracted to Temkin’s brand of egalitarianism.

The second objection to Temkin-style egalitarianism seems much more damaging. Imagine that scenario C is the status quo and one is deciding whether to support a move to scenario D (which would bring everyone in C down to the level of C’s worst-off group). Plainly, D is superior with respect to equality. But there is also no one for whom D would be better than C. And yet the Temkin-style egalitarian is forced to say that there is something to be said in favor of moving from C to D. Here again Temkin insists that despite being easily outweighed by other considerations, equality still has some value even in this case.

Again, this rebuttal is clearly open to Temkin. But here the antiegalitarian’s reply seems even stronger. She will highlight how bizarre it is to say there could be any reason to move from C to D, especially because no one is benefited and many people are significantly harmed. That is the Leveling-Down objection.

From Equality To Priority

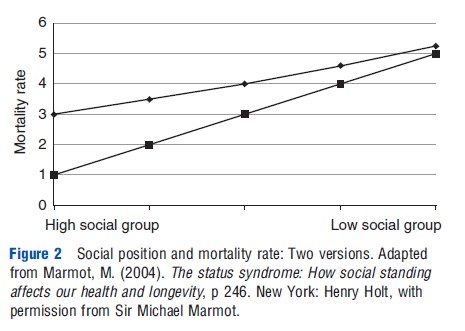

The Raising-Up and Leveling-Down objections lead many to give up entirely their belief in the intrinsic value of equality. But others, like Temkin, remain steadfast. Consider the following diagram, which replicates a diagram first drawn by Michael Marmot and discussed in his book The Status Syndrome (Marmot, 2004, p. 246) (Figure 2).

The diagram graphs the mortality effects of a policy change on four social groups arranged from left to right in descending order of social advantage. The top line (call it Diamond) depicts the current situation and the top line (call it Square) depicts what the situation would be after implementing the proposed policy. Thus, the policy widens inequalities in mortality. But Square also offers Pareto improvements over Diamond, because each social group in Square has lower mortality than the corresponding social group in Diamond. Marmot drew the graph during a conversation with Deaton. Deaton wanted to know if Marmot cared more about reducing inequalities than he did about reducing sickness and death. Marmot writes:

I demurred. [Deaton] was in no doubt that all economists would choose the bottom graph because everyone is better off….[He] suspected that I went for the one with less inequality where everyone suffered more…It is my view that we should reject both alternatives and aim for a society where health for everyone has improved and inequality is less (Marmot, 2004, pp. 245–246).

The economists Deaton referred to will likely be motivated by a commitment to Pareto improvements. In contrast, many philosophers who agree with Deaton’s choice of Square over Diamond will be driven by a belief in prioritarianism. There are a number of versions of prioritarianism, but its general thrust is that, morally speaking, benefiting people matters more the worse off they are. Although prioritarians will agree that there is often reason to promote greater equality, they do not think equality is intrinsically important. Rather, a system that tilts in favor of helping the worse off will often end up more equal merely as a side effect of the prioritarian focus on improving the disadvantaged. But if improving the lot of the worse off should require or entail increases in inequality, prioritarians (like many economists) will not care.

Once prioritarianism is introduced, an intrinsic concern with equality can seem like an esthetic preferences rather than a moral conviction. Where the egalitarian claims that things have gotten more unfair even though everyone is doing much better and even if the worst off are as well-off as possible, the prioritarian demands to know who (other than the egalitarian!) is complaining about unfairness. It cannot be the best off, because they are doing better than anyone and so have no right to complain. And it is unlikely to be the worst off, because they surely would not demand to be worse off than they already are.

The Value of Equality Revisited

Without concluding that Temkin-style egalitarianism is false, consider further the alternative of ‘opportunity prioritarianism,’ i.e., the view that social policy should tilt in favor of promoting the substantive life opportunities of those worse off (at least to the extent consistent with respecting individual choice and personal responsibility). Such a view sees nothing intrinsically valuable in distributive equality.

Consider now an objection to opportunity prioritarianism. When one looks outside the narrow sphere of personal prospects for pursuing worthwhile life opportunities, one encounters other spheres of life within which equality seems to have intrinsic importance. Consider the spheres of political liberty and social mobility. Many believe there is a presumption in favor of equality of access to political influence and equality of opportunity (whereby no child is systematically disadvantaged in their life prospects because of their parents’ socioeconomic status). If it seems appropriate to stress the intrinsic importance of equality in these political and socioeconomic domains, should this be interpreted as support by analogy for the intrinsic importance of equality within the narrower domain of personal life prospects?

The first thing to note is that the spheres of political influence and social mobility are zero sum. So even if one is a consistent prioritarian across the three domains of personal life prospects, political influence, and social mobility, equality will be the only distribution available for the last two domains: it is simply impossible to boost one social group’s share of political influence or social mobility without making another worse off. This does not of course prove that equality in these realms has no intrinsic value. But it might explain why one would remain attracted to distributive equality in some spheres even if one’s most fundamental ethical framework was prioritarian.

Further, if inequalities in life prospects led to unequal political influence, unequal social mobility, and to significant improvements in the range of worthwhile life plans open to those in lower- and middle-income groups, then the trade-off might be worth it on prioritarian grounds.

Of these two considerations – (1) that prioritarian inequalities are not possible in the local spheres of political liberty and social mobility and (2) that there may be prioritarian reasons to tolerate inequalities in more local spheres – neither proves conclusively that equality in these spheres is of no intrinsic importance. Indeed, there is one more way of conceiving of equality and its importance that differs from Temkin’s approach and that raises the possibility that egalitarian and prioritarian concerns are both valid and in fact closely related.

The Possibility of an Egalitarian Prioritarianism

It was suggested near the end of the Section From Equality to Priority that once prioritarianism is introduced, a commitment to distributive equality can begin to resemble an esthetic preferences for uniformity rather than a commitment to the real needs of individuals. However, many who hold egalitarian views about equal political influence and equal social mobility are not primarily motivated by a general desire to eliminate undeserved disadvantages between individuals. Rather, they are often moved by the independent values of nondomination, reciprocity, and equal social status. According to an increasing number of philosophers, these are the values that should ground egalitarian political convictions, as they are specially relevant for societies that care about treating all persons as moral equals. To say that each person is the moral equal of all is not yet to say that goods should be distributed in a particular way. So the ideal of moral equality is not, at bottom, a distributive ideal, although many claim that it has implications for the distribution of specific sorts of goods and for life opportunities generally. For example, distributive implications may flow from considerations about the demands of reciprocity and benevolent concern that are warranted when moral equals stand in particular social and political relationships with one another.

Some philosophers suggest that when prioritarian distributions are demanded by justice, this demand is ultimately grounded in these nondistributional premises about moral equality and ethically mandated concern (Miller, 2010). A stylized example of Thomas Nagel’s provides a useful illustration. In an essay that in many ways sparked the contemporary philosophical debate between distributive egalitarians and prioritarians, Nagel describes a fictional scenario in which he has one healthy child and one suffering from a painful disability. He imagines that he must make a choice between moving to a city where the second child could receive medical treatment but which would be unpleasant for the first child, or moving to a semirural suburb where the first child alone would benefit. He stipulates that ‘‘the gain to the first child of moving to the suburb is substantially greater than the gain to the second child of moving to the city.’’ Nagel then claims that, ‘‘If one chose to move to the city, it would be an egalitarian decision. It is more urgent to benefit the second child, even though the benefit we can give him is less than the benefit we can give the first child’’ (Nagel, 1991, p. 124). In response, Derek Parfit claims that Nagel has misdescribed his own moral commitments. Nagel says that the duty to attend to the disabled child’s needs is an egalitarian duty. Parfit insists that Nagel is not concerned with distributive equality between the two children at all, and that Nagel instead appears motivated by prioritarian concern for the worse off child. One might reply on Nagel’s behalf by claiming that Parfit works with a false dichotomy. In insisting that Nagel must be a prioritarian, Parfit ignores the brand of egalitarianism that stresses the moral demands of distinctive interpersonal relationships, including relationships that call for the display of equal and robust concern for those to whom one is specially related. When multiple individuals compete for that concern (as they may when they are our children or – plausibly but more controversially – our fellow citizens) it is reasonable to conclude that treating all of them as equals requires a prioritarian response to their diverse needs.

This last brand of egalitarianism – call it egalitarianism of concern – may hold great promise to unify and explain many intuitions about the demands of equity across multiple policy domains, including the domain of health policy. If, for example, it can be shown that compatriots or indeed ‘global citizens’ owe robust duties of equal concern for one another, then the distribution of medical care and other resources bearing on health should arguably follow whatever pattern is required to address the relevant needs of the worst off.

References:

- Deaton, A. (2002). Policy implications of the gradient of health and wealth. Health Affairs 21, 13–30.

- Deaton, A. (2011). What does the empirical evidence tell us about the injustice of health inequalities? In Eyal, N., Norheim, O. F., Hurst, S. A. and Wikler, D. (eds.) Inequalities in health: Concepts, measures, and ethics. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Hausman, D. (2010). Valuing health: A new proposal. Health Economics 19, 280–296.

- Marmot, M. (2004). The status syndrome: How social standing affects our health and longevity. New York: Henry Holt.

- Miller, R. W. (2010). Globalizing justice: The ethics of poverty and power. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Nagel, T. (1991). Equality. In Nagel, T. (ed.) Mortal questions, pp 106–127. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Scanlon, T. M. (2003). Value, desire, and the quality of life. In Scanlon, T. M. (ed.) The difficulty of tolerance: Essays in political philosophy, pp 169–186. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sen, A. (2002). Why health equity? Health Economics 11, 659–666.

- Temkin, L. (2003). Egalitarianism defended. Ethics 113, 764–782.

- Ubel, P. (2000). Pricing life. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Whitehead, M. (1991). The concepts and principles of equity and health. Health Promotion International 6, 217–228.

- Wilson, J. (2011). Health inequities. In Dawson, A. (ed.) Public health ethics: Key concepts in policy and practice, pp 211–230. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Daniels, N. (1994). Four unsolved rationing problems. Hastings Center Report 24(4), 27–29.

- Dworkin, R. (1981). What is equality? Part 1: Equality of welfare. Philosophy and Public Affairs 10(3), 185–246.

- Hausman, D. (2006). Valuing health. Philosophy and Public Affairs 34, 246–274.

- Kamm, F. M. (2009). Aggregation, allocating scarce resources, and the disabled. Social Philosophy and Policy 26(01), 148–197.

- Murray, C. J. L., Salomon, J. A., Mathers, C. D. and Lopez, A. D. (2002). Summary measures of population health: Conclusions and recommendations. In Murray, C. J. L., Salomon, J. A., Mathers, C. D. and Lopez, A. D. (eds.) Summary measures of population health, pp 731–756. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Parfit, D. (1997). Equality and priority. Ratio 10, 202–221.

- Sen, A. (1980). Equality of what? In McMurrin, S. (ed.) Tanner lecture on human values, vol. 1, pp 195–220. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Ubel, P., Loewenstein, G., Scanlon, D. and Kamlet, M. (1996). Individual utilities are inconsistent with rationing choices: A partial explanation of why Oregon’s cost-effectiveness list failed. Medical Decision Making 16, 108–116.