Introduction

The phrase ‘public health’ can be used to mean (1) population health, or (2) public policy intervention to prevent ill health. This article focuses on public health in the latter sense, as used by the public health profession and the broader public health community. However, the discipline of economics also has much to contribute to understanding public health in the former sense. So by way of background, this introductory section lists a few of the many contributions that economists have made to measuring population health and analyzing its determinants.

Contributions by economists to measuring population health include work by:

- Alan Williams and George Torrance in helping to develop the quality-adjusted life-year measure of overall health.

- Christopher Murray in helping to develop the Disability Adjusted Life Year measure of overall disease burden and the Global Burden of Disease reports, together with epidemiologist Alan Lopez.

What is distinctively ‘economic’ about these contributions, compared with contributions by clinicians, epidemiologists, psychologists, and others, is the development of overall summary measures of health that allow diverse mortality and morbidity outcomes from diverse health conditions to be compared with one another in terms of a common generic unit of health.

Contributions by economists to analyzing the determinants of population health include work by:

- Samuel Preston on distinguishing the contributions of income growth and new technology to improvements in population health in the twentieth century.

- Victor Fuchs on distinguishing the total contribution of healthcare to population health from the much smaller marginal contribution of additional health care expenditure at the current level of medical technology.

- David Cutler and Mark McClellan on the substantial health benefits of medical innovation in the latter half of the twentieth century, building on work by anesthesiologist John Bunker.

- Angus Deaton on disentangling the relationships between income, health, and wellbeing, including work addressing the hypothesis of social epidemiologist Richard Wilkinson that income inequality is a health hazard.

- David Grossman on the concept of health capital and the contribution of health capital investments over the life-course to the production of health.

- James Heckman, Janet Currie, and Robert Fogel on the contribution of in utero and early childhood circumstances to health and human capital formation, building on work by epidemiologist David Barker.

- Garry Becker on the theory of rational addiction and subsequent empirical work by Frank Chaloupka and others, confirming some (though not all) of its testable predictions in relation to smoking and other unhealthy addictive behaviors.

- Tomas Philipson on economic epidemiology and the role of prevalence-elastic prevention behavior in determining the prevalence of infectious disease.

- Don Kenkel on the role of antismoking public sentiment as a cause of both antismoking public policy and declining smoking rates, an example of the general issue of ‘endogenous policy’.

- Harold Holder on general equilibrium modeling of alcohol consumption (‘SimCom’), including feedback loops between alcohol consumption and policy formation.

What is distinctively ‘economic’ about these contributions includes the focus on marginal analysis (since marginal effects on health are more relevant to decision makers than average or total effects) and the focus on understanding how the health related behavior of individuals and organizations changes in response to changes in their incentives and constraints.

Other distinctive characteristics of these contributions include the recognition that individuals and governments have important objectives other than health improvement, the explicit modeling of complex causal pathways, and the focus on seeking robust estimates of effect using experimental and quasi-experimental methods. However, it is less clear that these are distinctively ‘economic’ characteristics as opposed to distinctive characteristics of high quality public health and social science research, more generally.

The Nature And Scope Of Public Health Intervention

Public health intervention is an important topic, for two reasons. First, preventing ill health is an important objective. Bad health is not only intrinsically bad but also instrumentally bad, as it makes it harder for people to lead flourishing lives and contribute to society by undertaking productive work, family, and social activities. Second, history suggests that public health intervention can succeed in preventing ill health. Careful analysis of historical mortality and fertility records by historian Simon Szreter and others has shown that the nineteenth century ‘sanitary movement’ and other historical public health interventions did contribute to the steady improvements life expectancy seen in the past 200 years, despite earlier findings to the contrary by physician Thomas McKeown.

Public health intervention is also a broad topic. In a 1920 article in Science, entitled ‘the untilled fields of public health’, the renowned US bacteriologist and professor of public health at Yale, Charles-Edward Amory Winslow, defined public health as: ‘‘the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life, and promoting physical health and efficiency through organized community efforts for the sanitation of the environment, the control of community infections, the education of the individual in principles of personal hygiene, the organization of medical and nursing service for the early diagnosis and preventive treatment of disease, and the development of the social machinery which will ensure to every individual in the community a standard of living adequate for the maintenance of health.’’ In 1988, the US Institute of Medicine put it more generally, and more succinctly: ‘‘Public health is what we, as a society, do collectively to assure the conditions for people to be healthy.’’

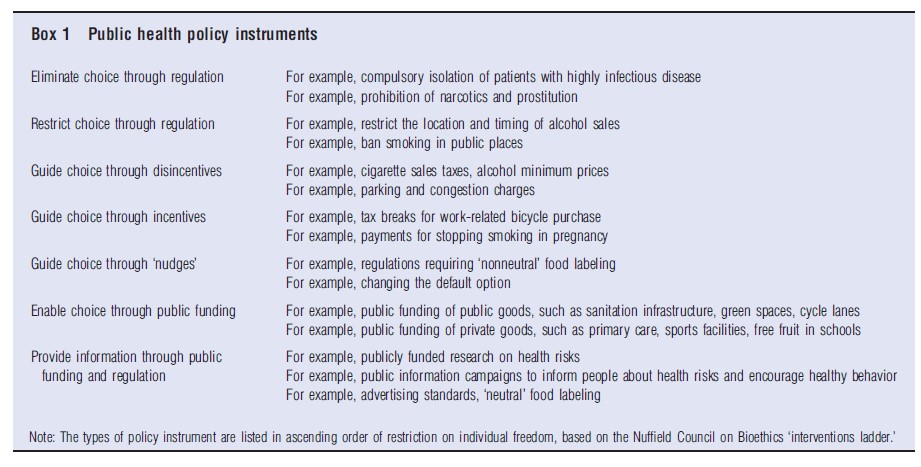

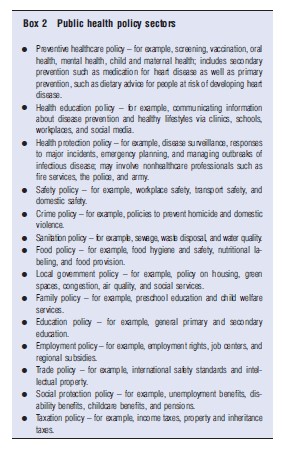

The scope of public health intervention thus potentially encompasses any kind of population level policy instrument (see Box 1) implemented by any kind of government or nongovernment organization or group in any sector of social or economic policy (see Box 2), which is undertaken with the (not necessarily exclusive) aim of preventing any kind of disease, illness, disability or injury, whether physical or mental, fatal or nonfatal, mild or severe.

Public health differs from healthcare insofar as it involves public policy intervention to reduce the risk of future ill health, rather than to treat current ill health. The risk reductions caused by particular public health interventions are often small and imperceptible at individual level, but can add up to large and tangible benefits at population level. Indeed, public health interventions that deliver small reductions in individual health risk to a large population of relatively healthy people can offer greater total health benefits than healthcare interventions that deliver large individual benefits to a small population of relatively unhealthy people. This is known as the ‘prevention paradox’, a term coined by the epidemiologist Geoffrey Rose.

Two great pioneers of public health in the nineteenth century were Edwin Chadwick and John Snow. In 1843, Chadwick’s Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain helped catalyze the sanitary movement that substantially contributed to increases in life expectancy across the globe. Snow is widely considered to be the father of modern epidemiology, following his classic 1855 treatise, On the Mode of Communication of Cholera. Among other things, this treatise reports his famous 1848 study that convincingly traces the cause of an outbreak of cholera in London to the Broad Street water pump by collecting data to test rival hypotheses.

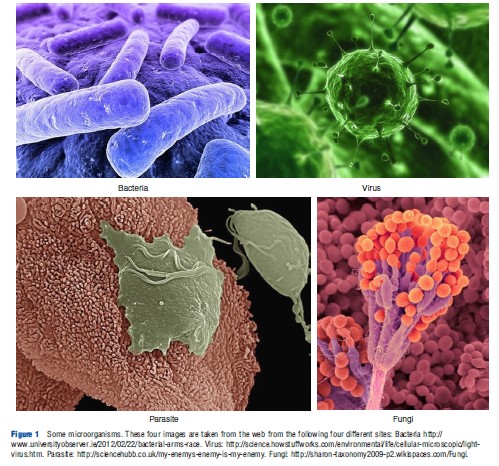

In the nineteenth century, the central task of public health intervention has been to prevent communicable or infectious diseases, to which young children are particularly vulnerable. These ‘infectious diseases of childhood’ are now reasonably well controlled in most parts of the world, but there is still a substantial burden of disease among young children in much of Africa and Asia from cholera and other diarrheal diseases, lower respiratory diseases, meningitis, tetanus, measles, tuberculosis, malaria, HIV/AIDs, leishmaniasis, hepatitis, leprosy, and other infectious diseases (Figure 1).

Infectious agents such as viruses, bacteria, and parasites or fungi can spread directly from person to person, and people can also shed them into the air or water or onto food or other surfaces where other people may come into contact with them. Infectious diseases therefore generate ‘technological externalities’: one person can change another person’s risk of infection through their actions, without bearing any of the costs or gaining any of the benefits of that change. Externalities provide a standard economic rationale for government intervention to prevent infectious disease, for example though investment in sanitation infrastructure or quarantine regulations. Public infrastructure investments to prevent infectious disease – such as building sewers, or draining malaria-infested swamps – can be seen as ‘public goods’ in the technical economic sense of being nonexcludable and nonrival: no one can be excluded from use, and one person’s use does not reduce the good’s availability to others. Governments have a role in providing such public goods, because markets have difficulty providing goods that customers can easily consume within paying anything.

Since the nineteenth century, much of the world has undergone a ‘demographic transition’ from high to low rates of birth and death. This has important implications for public health in the twenty-first century, which is increasingly focusing on the prevention of noncommunicable chronic diseases and disorders to which older people are particularly vulnerable, such as circulatory diseases, cancers, diabetes, neurological disorders, and musculoskeletal disorders. The nature of this prevention task is different, as one of the main ways of preventing (or, at least, delaying) these ‘chronic diseases of old age’ is to encourage people to adopt healthier lifestyle behaviors in relation to diet, physical activity, smoking, drinking, substance abuse, and musculoskeletal load. Technological externalities are largely irrelevant to lifestyle behavior, insofar as an unhealthy lifestyle only harms the individual’s own health – though of course, there are exceptions such as passive smoking and drink driving. So public health interventions to promote healthy lifestyles are not ‘public goods’ in the technical economic sense. However, there may be other economic justifications for such interventions, as discussed below.

In most countries, public health interventions in each of the policy sectors listed in Box 2 are planned and implemented by at least one and usually many different organizations. It therefore stretches credulity somewhat to talk about a public health ‘system,’ as if the organizations in these diverse areas of social and economic policy were all exclusively designed for the purpose of working together to improve population health. Nevertheless, most countries do attempt a degree of coordination between public health interventions in different policy sectors, in at least two ways. First, though an officially recognized ‘public health profession,’ such as the US Public Health Service Commissioned Corps and the UK Faculty of Public Health, whose members implement many different public health functions and lead some of the relevant public policymaking agencies. Second, through the appointment of senior policymakers and policymaking agencies with responsibility for cross-government coordination of public health policy, such as the Surgeon General and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the US, and the Chief Medical Officer and Public Health England in the UK.

Economic Arguments For Government Intervention In Public Health

One can distinguish five types of normative economic argument for government intervention in public health:

- Asymmetric information

- Technological externality and public goods

- Pecuniary externality

- Paternalism and bounded rationality

- Equity

The first two are classic ‘market failure’ arguments, which show how fully rational and self-interested market participants can fail to achieve a Pareto efficient outcome due to the presence of a single distortion or imperfection in an otherwise perfect market setting. When markets fail in this sense, it may be possible for government intervention to deliver a Pareto improvement that makes at least one person better off without making anyone else worse off – though this possibility may be constrained by sources of government failure, such as asymmetries of information between government officials and market participants, and self-interested behavior by government officials. The third type of argument relies on the welfare economic ‘theory of the 2nd best’ in the presence of more than one market distortion. The fourth type of argument relies on individuals being less than fully rational and self-interested. The final type of argument goes beyond market failure in terms of Pareto inefficiency and analyses distributional concerns for equity or justice.

Asymmetric information refers to a situation in which one party to a market transaction has better information than another party. Healthcare markets are pervaded by asymmetries of information – between doctors and patients, insurers and insurees, buyers and sellers of new medical technology, and so on. These asymmetries may help to justify government intervention in both curative and preventive healthcare. Information asymmetries are also relevant outside the healthcare market. For example, sellers may have better information than buyers about the health risks associated with consuming their goods and services; and employers may have better information than employees about the health risks associated with their working conditions. This asymmetry can provide a market failure argument for ex ante safety regulation (e.g., health and safety requirements enforced by licensing and inspection processes, advertising standards, requirements for provision of safety information) and ex post tort law compensation claims for health damages caused by transactions made on the basis of hidden information. Note, however, that it is the asymmetry of information between market participants about health risk that distorts market behavior and generates market failure, rather than the mere presence of health risk or the mere lack of perfect information about the true nature of health risk. For example, asymmetry of information about the health risks of smoking in the 1950s between tobacco company executives and consumers may have generated market failure. By contrast, continuing uncertainty and imperfect information among all market participants about how far smoking will damage any particular individual’s health do not generate ‘market failure’ in the classic economic sense.

In their renowned 1988 textbook on the theory of environmental policy, William Baumol and Wallace Oates define a technological externality as follows: ‘‘An externality is present whenever some individual’s (say A’s) utility or production relationships include real (that is, nonmonetary) variables, whose values are chosen by others (persons, corporations and governments) without particular attention to the effects on A’s welfare.’’ This definition clearly applies to infectious disease externality, because individual A’s utility depends on the number and type of infective microorganisms present in their living and working environments, which in turn depends on choices made by other persons, corporations, and governments. It also applies to passive smoking, drunk driving, and other cases, in which individual A’s risk factors for noncommunicable disease or injury are directly influenced by other people’s choices. It is less clear whether it applies to cases in which individual A’s health risk factors are indirectly influenced by other people’s choices through their influence on individual A’s own choices – for example, choices generating congestion and crime in the local area, which influence individual A’s choices about physical activity.

As described earlier, an important class of technological externalities in public health are nonexcludable and nonrival public goods such as investment in sanitation infrastructure to prevent the spread of infectious disease. Public investment in basic universal healthcare and education systems in low and middle income countries also has public good characteristics. Almost everyone is better off living in a high income country with a healthy population and a growing economy (even the super-rich). Yet, the market alone may fail to coordinate this large and sustained infrastructure investment, precisely because almost everyone benefits, whether they pay or not. Another important example of a public good is the creation of new information about health risk through research and development (R&D). R&D is a nonrival and nonexcludable good insofar as the new information it generates can subsequently be acquired by potential beneficiaries at very low cost and is hard to keep secret. These ‘information externalities’ may help to justify R&D subsidy and government regulation of intellectual property rights, such as patent protection and copyright legislation. It is less clear that information externalities help to justify public health information campaigns, however, because the transmission of existing information (as opposed to the generation of new information) often has the characteristics of a private good – for example, leaflets (as opposed to the information they contain) are excludable goods.

A quite different form of externality arises in the case of external costs imposed upon taxpayers due to public expenditure on health and social care. Here, the externality is monetary or ‘pecuniary’ in nature, and not a real variable entering into utility or production relationships. According to the welfare economic ‘theory of the 2nd best’, pecuniary externalities can nevertheless cause market failure to achieve a constrained Pareto efficient outcome in economies with multiple market imperfections (such as information asymmetries, taxes, and so on). However, this argument needs to be used with caution, as policy prescriptions from ‘2nd best’ welfare economic analyses are context-dependent and sometimes counter-intuitive, and it is hard to construct realistic models of actual economies with multiple imperfections.

Another note of caution is that pecuniary externalities are ubiquitous, and can be used as a spurious justification by all sorts of interest groups seeking special favors. For example, there is a pecuniary externality argument for subsidizing private schools, on the grounds that sending a child to private school may reduce the cost of operating public schools. A further note of caution is that pecuniary externality arguments for public health intervention can be a double edged sword. For example, preventing smoking may reduce taxpayer expenditure on healthcare for lung cancer but may increase taxpayer expenditure on pensions and long-term care for those who survive longer. Hence, whether the pecuniary externality associated with a particular form of unhealthy behavior is positive or negative is an open empirical question, and will depend on the context. A final note of caution is that the root cause of pecuniary externalities on taxpayers is government intervention – in this case, public programs offering free health and social care. Some economists argue that limiting entitlements to free health and social care may be a more attractive way of reducing pecuniary externalities than introducing new taxes on unhealthy behavior. Whatever the pros and cons of the latter argument, policymakers do need to bear in mind that taxes can have high administrative costs and unintended behavioral effects. For example, the Danish government introduced a tax on saturated fats in 2011 but rescinded it a year later. According to a newspaper report in The Economist in November 2012, ‘‘in practice, the world’s first fat tax proved to be a cumbersome chore with undesirable side effects. The tax’s advocates wanted to hit things like potato crisps and hot dogs, but it was applied also to high-end fare like speciality cheeses… Besides the bother and cost of installing new systems to calculate the extra tax, retailers were also hit by a surge in cross-border shopping.’’

The fourth argument – paternalism and bounded rationality – rests on the view that individuals sometimes fail to act in their own best interests, for example, due to weakness of will or limited information-processing ability. There is by now plenty of evidence from behavioral economics and psychology that individual rationality is imperfect in various ways. For example, people’s choices are often strongly influenced by nonrational ‘cues’ in their decision-making environment. In their book, ‘Nudge,’ Cass Sunstein and Richard Thaler use this kind of evidence as an argument for ‘soft’ paternalism, which involves altering the nonrational cues in order to gently ‘nudge’ people toward choices in line with their own best interests as perceived by the paternalistic decision maker. However, one can also use evidence of bounded rationality to make a case for ‘hard’ paternalism involving traditional public health instruments, such as taxes, subsidies, and regulations, which alter the incentives and constraints that people face. In the phrase of Adam Oliver from the London School of Economics, there may be a role for interventions that firmly ‘budge’ people toward rational ill health prevention behaviors as well as interventions that gently ‘nudge’ them.

Finally, the fifth argument – equity – relates to concerns about distributional fairness rather than Pareto efficiency. Some economists take the view that distributional concerns are not a proper subject for economic analysis (e.g., the great early twentieth-century economist, Lionel Robbins). However, other economists (e.g., Tony Atkinson and Amartya Sen) adopt a more inclusive ‘social choice’ approach to normative economics based on explicit analysis of social objectives, which may or may not include Pareto efficiency. Markets may give rise to substantial social inequalities in health and in ill health prevention activities, and social decision-makers may regard the reduction of such inequalities as a policy objective. This is a ‘specific egalitarian’ objective, rather than the ‘general egalitarian’ objective of redistributing income. According to classical ‘1st best’ welfare economic theory, redistribution of income is the most efficient way to reduce inequality in the distribution of welfare between individuals, rather than government intervention in specific markets such as the market for ill health prevention services. However, this theoretical result does not carry over into ‘2nd best’ economies with multiple imperfections, and so there is no general economic case against ‘specific egalitarian’ policy objectives. Nevertheless, there are dangers with making egalitarian objectives overly specific. For example, one would not want to focus exclusively on reducing social inequality in the uptake of bowel cancer screening services without setting this in the context of more important and more general objectives such as reducing social inequality in bowel cancer mortality and life expectancy.

Economic Evaluation In Public Health

The previous section reviewed potential normative economic justifications for government to ‘do something’ in public health, rather than leave things to the market. However, these theoretical arguments only go part of the way toward justifying particular public health interventions. Government intervention in public health often imposes costs on public budgets, taxpayers and/or businesses, thus requiring an investment of scarce resources, which could be used for other potentially beneficial purposes. To justify this investment, evidence and analysis are needed to show that the particular government intervention under consideration represents good ‘value for money’ compared with alternative uses of scarce resources. This is what the economic evaluation of public health interventions seeks to establish. Undertaking such economic evaluations – while being time and resource-intensive activities in themselves – is useful for at least three reasons:

- Improving public policy outcomes: Economic evaluation can help improve outcomes by helping policymakers identify potentially worthwhile and potentially wasteful public health interventions based on the best available international research evidence.

- Improving clarity of thought: Economic evaluation can help public policymakers think through systematically the pros and cons of alternative ways of designing and implementing public health interventions in their own decision-making context.

- Improving public accountability: Economic evaluation can help hold public policymakers to account by identifying and publishing the factual assumptions and social value judgments underpinning their decisions.

The economic way of thinking about the costs and benefits of public health interventions can be contrasted with two commonly held but misguided alternative ways of thinking. In his classic health economic monograph, ‘Who Shall Live?,’ Victor Fuchs memorably dubbed these the ‘romantic’ and ‘monotechnic’ points of view, respectively. The ‘romantic’ point of view denies that resources are scarce and that resource allocation decisions have opportunity costs in terms of alternative beneficial uses of scarce resources. The ‘romantic’ believes that resources can be found for their own favoured cause without impinging on other people’s favored causes – for example, by making ‘efficiency savings,’ by diverting resources from disfavored causes (such as defense spending) or by clamping down on the high pay and tax avoidance behavior of the super rich. Fuchs criticizes this viewpoint, writing that: ‘‘Because some of the barriers to greater output and want satisfaction are clearly man-made, the romantic is misled into confusing the real world with the Garden of Eden.’’ He goes on: ‘‘Confronted with an obvious imbalance between people’s desires and the available resources, the romantic-authoritarian response may be to categorize some desires as ‘unnecessary’ or ‘inappropriate’, thus protecting the illusion that no scarcity exists.’’ By contrast, the ‘monotechnic’ point of view fails to recognize the legitimate plurality of individual and social objectives. The ‘monotechnic’ fixates on a single objective and is unconcerned if allocating additional resources to this objective imposes opportunity costs in terms of other objectives. According to Fuchs, the ‘monotechnic’ view is ‘‘frequently found among physicians, engineers, and others trained in the application of a particular technology.’’ He goes on to write: ‘‘The desire of the engineer to build the best bridge or the physician to practice in the best-equipped hospital is understandable. But to extent that the monotechnic person fails to recognize the claims of competing wants or the divergence of his priorities from those of other people, his advice is likely to be a poor guide to social policy.’’

Various organizations have adopted a systematic cost-effectiveness approach to evaluating public health interventions, in line with standard health technology assessment methods being used to evaluate clinical healthcare sector interventions. Publicly accessible repositories of this kind of evidence, each of which assesses the cost-effectiveness of a fairly wide range of public health interventions using a common set of methods, include the WHO-CHOICE database, the US Preventive Services Task Force, the UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence public health guidance, and the ACE-Prevention project in Australia.

However, standard cost-effectiveness analyses of this kind are somewhat less useful in public health than in the healthcare sector, for at least four reasons. First, randomized control trial (RCT) data are scarce, so it is hard to attribute effects to interventions, and the exploitation of ‘natural experiments’ using large observational datasets is still in its infancy in public health. This means that existing repositories of cost-effectiveness evidence in public health are forced to chart a difficult course between the Scylla of ‘RCT fetishism’ (i.e., focusing unduly on clinically-oriented types of intervention for which RCT data exist) and the Charybdis of ‘practitioner bias’ (i.e., using overly favorable effect size estimates based on the opinions of a small coterie of policy enthusiasts rather than robust evidence). Second, important costs and benefits often fall outside the healthcare sector – including costs on taxpayers, business and government agencies, and including a variety of nonhealth benefits such as improvements in education, employment, and crime outcomes. This means that cost-effectiveness analyses focusing on health benefits and healthcare sector costs only may not be relevant to the most important decision makers and stakeholders. Third, public health interventions often have explicit policy objectives relating to inequality reduction. Standard cost-effectiveness analysis does not examine the distribution of costs and benefits, and hence cannot offer policymakers any guidance on the existence and nature of potential trade-offs between concerns for efficiency and equality. Finally, some public health interventions have long-term benefits that arise decades in the future – including benefits to future generations. Standard cost-effectiveness analysis does not explicitly distinguish effects on current and future generations, and the standard approach to discounting implies a hefty penalty to health benefits arising many decades in the future – for example, a 5% discount rate implies that a life-year gained in 50 years time is valued at only 7.7% of a life-year gained this year; or 0.6 of 1% in 100 years time.

There are public repositories of cost–benefit analysis evidence of social policies, which take a broader approach and address some (but not all) of these issues – for example, the Washington State Institute of Public Policy. To date, however, cost-benefit analyses of social policies tend to focus on nonhealth benefits; and if health effects are incorporated at all, they tend to be based on mortality and the saving of ‘statistical lives’ rather than more comprehensive analysis of effects on length of life and health-related quality of life.

As Helen Weatherly and colleagues from the University of York have argued therefore, more research is needed to produce more useful economic evaluations of intersectoral public health policies, including not only the application of existing cost– consequence analysis and cost–benefit analysis approaches, but also methodological research to develop new approaches.

Conclusion

In line with most of the existing economic literature on public health, this article has adopted a standard ‘social choice’ approach to normative economics, which focuses on providing analysis and evidence that will be useful to a perfectly benevolent social decision-making institution seeking to achieve a set of socially desirable objectives in the face of market failure. However, it is also possible to adopt a ‘public choice’ approach that treats government institutions as economic agents with nonbenevolent or at least imperfectly benevolent objectives. Economic models of interest group lobbying, rent seeking, and bureaucratic incentives, can all help to understand government behavior in relation to public health, why some public health interventions are more likely to be adopted than others, and why actual decision-making in public health so often departs from policy prescriptions based on standard ‘social choice’ analyses of the kind described in this overview.

Another important frontier in public health research is the role of behavioral economic evidence and insights in helping to design more effective public health interventions. As described earlier, global economic growth means that the task of public health is increasingly shifting away from preventing the ‘infectious diseases of childhood’ toward preventing the ‘chronic diseases of adulthood.’ This implies a shift in the nature of the economic problem away from market failures due to infectious disease externality, toward market failures due to bounded rationality that generates unhealthy lifestyle behavior. There is thus an important new role for behavioral economic research into the nature of bounded rationality and the potential role of interventions to improve lifestyle behavior through appropriate ‘nudges’ and ‘budges’.

Finally, a third important frontier for economic research is the economic evaluation of cross-sectoral public health interventions. Compared to the cost-effectiveness analysis of healthcare technologies, the evaluation of public health interventions poses additional – or, rather, more severe – challenges that require the development of new methods. These methodological challenges include (1) estimating health effects when RCT evidence is scarce, (2) measuring and valuing nonhealth benefits alongside health benefits, (3) analyzing costs falling outside the government healthcare budget, (4) analyzing distributional concerns when reducing inequality is an explicit policy objective, and (5) valuing long-term health and nonhealth benefits including benefits to future generations.

Bibliography:

- Akinson, A. B. (2011). The restoration of welfare economics. American Economic Review 101(3), 157–161.

- Browning, E. K. (1999). The myth of fiscal externalities. Public Finance Review 27, 3–18.

- Carande-Kulis, V. G., Getzen, T. E. and Thacker, S. B. (2007). Public goods and externalities: A research agenda for public health economics. Journal of Public Health Management Practice 13(2), 32–227.

- Cawley, J. and Ruhm, C. J. (2011). Chapter three – The economics of risky health behaviors. Handbook of health economics 2, 95–199.

- Colgrove, J. (2002). The McKeown thesis: A historical controversy and its enduring influence. American Journal of Public Health 92(5), 725–729.

- Greenwald, B. and Stiglitz, J. E. (1986). Externalities in economies with imperfect information and incomplete markets. Quarterly Journal of Economics 101, 229–264.

- Kenkel, D. and Suhrcke, M. (2011). Economic evaluation of the social determinants of health – A conceptual and practical overview. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. Available at: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/155579/e96075.pdf

- Loewenstein, G., Asch, D. A., Friedman, J. Y., Melichar, L. A. and Volpp, K. G. (2012). Can behavioural economics make us healthier? British Medical Journal.

- Marteau, T. M., Ogilvie, D., Roland, M., Suhrcke, M. and Kelly, M. P. (2011). Judging nudging: Can nudging improve population health? British Medical Journal.

- Philipson, T. J. (2008). Economic epidemiology. In Durlauf, Steven N. and Blume, Lawrence E. (eds.) The New Palgrave dictionary of economics online, 2nd ed. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Porter, D. (1998). Health, civilization, and the state: A history of public health from ancient to modern times. New York: Routledge.

- Rose, G. (1992). The strategy of preventive medicine. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Sretzer, S. (1988). The importance of social interventions in Britain’s mortality decline c. 1850–1914: A re-interpretation of the role of public health. Society for the Social History of Medicine 1, 1–37.

- Vining, A. and Weimer, D. L. (2010). An assessment of important issues concerning the application of benefit-cost analysis to social policy. Journal of Benefit-Cost Analysis 1(1), 1–40.

- Weatherly, H., Drummond, M., Claxton, K., et al. (2009). Methods for assessing the cost-effectiveness of public health interventions: Key challenges and recommendations. Health Policy 93, 85–92.

- https://www.healthknowledge.org.uk/public-health-textbook HealthKnowledge Free On-Line Public Health Textbook.

- https://www.sagepub.com/sites/default/files/upm-binaries/3989_Chapter_1.pdf Population-Based Public Health Practice.

- https://www.fph.org.uk/ UK Faculty of Public Health.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_health Wikipedia Entry on Public Health.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_health_law Wikipedia Entry on Public Health Law.

- https://www.who.int/teams/health-promotion/enhanced-wellbeing/first-global-conference WHO 1986 Ottowa Charter for Health Promotion

- https://public-health.uq.edu.au/ School of Public Health.

- https://www.gapminder.org/ Gapminder – The Wealth and Health of Nations.

- https://www.healthdata.org/gbd/data-visualizations Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Visualizations.

- https://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/ UCL Institute of Health Equity.

- https://www.who.int/teams/health-systems-governance-and-financing/economic-analysis WHO Economic Evaluation & Analysis.

- https://www.who.int/teams/social-determinants-of-health WHO Social Determinants of Health.