Introduction

Equity in the delivery of health care is an important policy objective in many countries, and some, such as Australia, Canada, Sweden, and the UK, distribute healthcare resources on the basis of explicit equity objectives. Such objectives often subscribe to egalitarian goals, which suggest that health care should be distributed according to need and financed according to ability to pay.

Egalitarian goals can include horizontal and/or vertical equity principles. The horizontal equity principle requires that individuals with the same needs receive the same treatment. The vertical equity principle requires that those with different needs receive appropriately different treatment. Taken together, these principles suggest not only that patients with the same needs should receive the same treatment irrespective of, for instance, their social class or place of residence, but also that those with greater needs should be appropriately prioritized in receiving health care.

In the literature, little attention has been paid to vertical equity in the delivery of health care. This is probably because measuring vertical equity requires strong value judgments regarding the way healthcare delivery ought to vary amongst individuals with different levels of need. Most empirical work considers horizontal equity, though the importance of vertical equity is increasingly being emphasized. When considering the role that health care might play in reducing inequalities in health, some authors have argued that accounting for vertical equity in the delivery of health care addresses health inequalities that will not be addressed by focusing only on horizontal equity. For example, it has been suggested that horizontal equity is not relevant when dealing with individuals with substantial differences in health status. The Marmot review (Marmot, 2010) concluded that in order to reduce the steepness of the social gradient in health, ‘‘actions must be universal, but with a scale and intensity that is proportionate to the level of disadvantage.’’ The review named this principle ‘proportionate universalism,’ which is related to the principle of vertical equity.

Crucial to the measurement of vertical equity are measures of ‘healthcare delivery’ and ‘need.’ ‘Healthcare delivery’ is a broad term that can be used to refer to the receipt of treatment, the use of, or access to, healthcare services, or to the allocation of healthcare resources between individuals or areas. In economic studies of equity, healthcare delivery typically refers to the use of healthcare services by individuals or to the allocation of healthcare resources to areas.

Although a wide variety of definitions of need have been developed, economists often define need in terms of ‘capacity to benefit’ – the ability to benefit from healthcare provision. In empirical studies, however, need is usually defined in terms of ill-health, where people who are ill are deemed to have greater need than those who are not. This is an imperfect measure, because unlike capacity to benefit, it does not account for the instrumentality of need, i.e., that needs for health care when ill only exist if there is health care available that can improve health. Although it is a limitation, this definition is used for pragmatic reasons in that measures of ill-health are often directly available in datasets used to measure equity, whereas measures of capacity to benefit are not available.

Another limitation, also commonly adopted for pragmatic reasons, is that empirical studies usually measure ill-health and healthcare delivery contemporaneously, when ideally need would be measured prior to utilization so that its causal impact on utilization could be assessed.

When investigating inequity in healthcare delivery, it is common to distinguish between ‘need variables’ which ought to affect healthcare delivery and ‘nonneed variables’ which ought not to. Inequality in healthcare delivery can be associated with both need and nonneed variables. There is horizontal inequity when healthcare delivery is affected by nonneed variables, so that individuals with the same needs consume different amounts of care. There is vertical equity when individuals with different levels of need consume appropriately different amounts of healthcare. The categorization of variables, such as age, gender, income, and ill-health, as need or nonneed variables is crucial to testing for horizontal and vertical inequity. The measurement of horizontal and vertical equity rests on value judgments as to what are need and nonneed variables and what constitutes an appropriate level of health care.

Notably, there are methodological challenges associated with measuring vertical equity, and as a result few studies have investigated this issue. Among these studies, there is considerable variation in the methods used and in the assumptions underpinning the analyses. In this article, these methods are reviewed and appraised; approaches taken outside the field of health care to measure vertical equity are also examined.

A Simple Model Of Vertical Equity

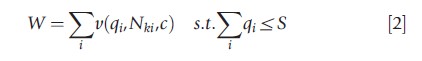

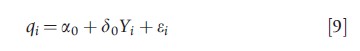

Gravelle et al. (2006) have described the conditions for the identification of and distinction between vertical and horizontal inequity in healthcare delivery, and have highlighted the main challenges faced by economic studies of equity in health care. They place equity analyses in the context of welfare maximization. For example, let v be the individual welfare accruing to individual i from the consumption of health care q, from k need characteristics N, and from the cost of accessing health care, c:

![]()

The aim of the policy maker is to enable individuals to choose utilization levels q that maximize an aggregate welfare function W subject to the constraint that total utilization cannot exceed total supply S:

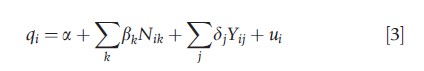

In the optimal allocation, which meets the horizontal and vertical equity principles, healthcare consumption is not affected by nonneed variables, and the effects of the need variables on consumption reflect the appropriate difference in treatment that individuals with different levels of need ought to receive. Consider a model of actual health care use given by

where Yj denotes a set of j nonneed variables that ought not to affect healthcare use. The condition for horizontal equity is δj =0, i.e., use is not affected by nonneed variables. The conditions for vertical equity are βk=β*k and a=a*, where β*k and a* denote the appropriate effect of the need variables on healthcare use, however, defined, and the optimum base level of consumption from the optimal healthcare allocation, respectively.

Vertical Equity In Healthcare Delivery

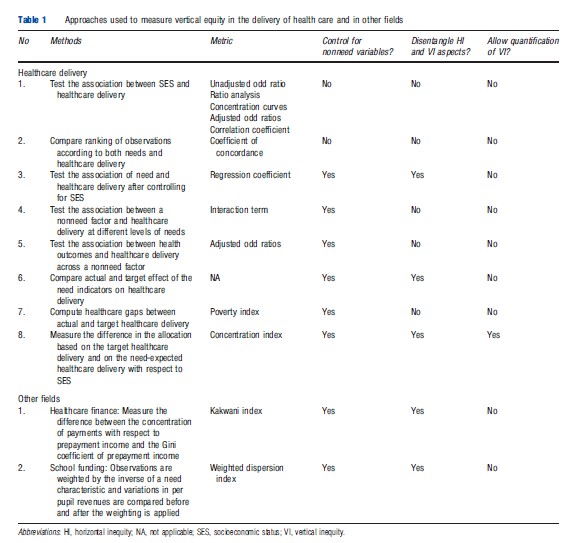

In this section, different approaches that have been taken to measure vertical equity in healthcare delivery are reviewed. Following Gravelle et al. (2006), the criteria for assessing the different approaches are based on: distinguishing between need and nonneed variables; testing the potential impact of omitted variables; disentangling horizontal and vertical equity; and measuring the extent of vertical inequity. The different approaches to defining the appropriate way in which healthcare consumption ought to vary for individuals with different levels of needs is also considered.

Separation between need and nonneed variables depends largely on value judgments on what counts as a need variable and what counts as a nonneed variable. It is commonly accepted that measures of health status and morbidity ought to affect healthcare use. In individual-level analyses with health and morbidity data, socioeconomic indicators are generally considered to be nonneed indicators. In the case that needs are not comprehensively measured, socioeconomic indicators may be picking up the effects of unobserved need factors, such as unmeasured severity levels. In that case, the analysis would be affected by an omitted variable problem. Although the extent to which needs are captured depends largely on the availability of the data, one criteria for assessing the different approaches is the ability of such approaches to account for needs comprehensively.

The exploration of vertical equity requires estimating the appropriate way in which healthcare consumption ought to vary for individuals with different levels of needs. Without the knowledge about the optimal effect of needs on healthcare delivery, conclusions about whether individuals with different needs are being appropriately treated cannot be made. In addition, the separation between vertical and horizontal aspects is not straightforward. This is because both need and nonneed variables are likely to be related. For instance, if on average, healthy individuals consume more health care than they ought to (i.e., there is evidence of vertical inequity favoring the relatively healthy – pro-healthy vertical inequity) and there is a positive correlationbetween health and income, then probably on average, richer individuals will consume more health care than they ought to; there is horizontal inequity favoring the rich (prorich horizontal inequity). More generally, if health and income are positively correlated, prohealthy vertical inequity will tend to benefit those on higher incomes, leading to prorich horizontal inequity. Conversely, propoor horizontal inequity will tend to mean that the sick have higher than expected levels of use, leading to prosick vertical inequity. Therefore, separation of vertical and horizontal inequity aspects is an important challenge in measuring vertical equity in healthcare delivery.

Finally, the simple model described in Section A Simple Model of Vertical Equity can be used to identify vertical and horizontal inequities in healthcare delivery, but it does not allow measurement of the extent of inequity; it is not possible to measure this purely on the basis of the size of a and b in eqn [3]. However, this is of interest because it permits comparisons over time and between areas, which is helpful both to identify trends and for policy evaluation.

Approaches To Measuring Vertical Equity In Healthcare Delivery

The following eight approaches, summarized in Table 1, have been used to measure vertical equity in healthcare delivery. Each of them has been explained, moving from the simplest to the more complex, and the limitations of each approach are assessed.

Approach 1: The Association Between Socioeconomic Status And Healthcare Delivery

This approach assumes that vertical equity is identified by a positive association between socioeconomic status (SES) and the delivery of health care. The assumption underpinning this approach is that individuals in lower socioeconomic groups have higher needs and they should therefore receive more health care in order to meet the vertical equity principle.

Let qi denote the quantity of healthcare delivery and Yi the SES for individual i. Higher values of q and Y denote greater healthcare use or resources and higher SES, respectively. Note that in this approach Y is used as a proxy for need and not as a nonneed variable. The test for vertical equity is based on the relationship between qi and Yi:

There is vertical equity if SES is negatively correlated with healthcare use (i.e., δ<0). Among the studies that have used this approach, the relationship between SES and healthcare delivery has been explored by different bivariate measures such as unadjusted odd ratios, ratio analysis, concentration curves, and correlation coefficients (Table 1).

In the absence of good epidemiological data, area-level analyses often rely on socioeconomic indicators as need variables. However, the choice of SES as a need variable is contested, and in many other studies, SES is defined as a nonneed variable. Although the correlation between SES and health is well documented, it does not imply that differences in SES will only be reflecting differences in needs. Moreover, there may be needs that are not correlated with SES that will not be picked up by an analysis of this kind. Therefore, the interpretation of the association between SES and healthcare delivery is ambiguous. These analyses are also not able to distinguish between vertical or horizontal inequity, as they cannot judge whether individuals receive different amounts of health care because of their different needs or because of same needs but different nonneed variables (e.g., SES). Even if SES was an appropriate need variable, this type of analysis cannot identify whether or not the differences in treatment received by those in lower SES is appropriate to meet their relatively higher needs. Nor can it measure the extent of vertical equity. Therefore, this approach is of limited use for analyzing vertical equity in healthcare delivery.

Approach 2: Comparison Of The Ranking Of Observations According To Both Needs And Healthcare Delivery

This approach assumes that vertical equity is identified by a positive correlation between the ranking of healthcare delivery and that of need. The method is thus based on a comparison of the hierarchy of observations when ranked according to both needs and the delivery of health care received. For example, this approach involves creating a need index based on health status, ranking observations with respect to need, and comparing this ranking with another ranking based on some measure of healthcare delivery. A measure such as Kendall’s coefficient of concordance between the two rankings could be used to indicate vertical inequity.

Inappropriate ranking in the allocation of health care with respect to needs could be due to deviation from either the horizontal or the vertical equity principles. Therefore, this method cannot distinguish between horizontal and vertical aspects of inequity, nor does it control for nonneed factors. Furthermore, although the method provides a framework for testing if the delivery of health care is ordinally appropriate, it fails to account for whether or not the allocation is cardinally appropriate. The measurement of vertical equity requires that the size of the differences in healthcare delivery between observations is sufficient to account for their relative differences in needs. Hence, this method is also of limited use for measuring vertical equity in healthcare delivery.

Approach 3: The Association Between Need And Healthcare Delivery

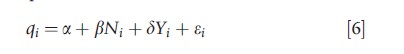

This approach assumes that vertical equity is identified by a positive correlation between healthcare delivery and need variables, usually measured by one or more health measures, after controlling for nonneed variables, commonly measured in terms of SES. It focuses on the idea that a positive association between healthcare delivery and ill-health is a necessary condition for vertical equity. Following from eqn [4], let N denote a measure of ill-health for individuals i, so that the test for vertical equity in healthcare delivery is that β>0, i.e., the need variable has a positive association with use:

Most studies using this approach have tried to incorporate some assessment of vertical equity by looking at the coefficients of the need variables that have been included in their regression models testing for horizontal inequity.

The approach is a simplified version of the test for vertical equity presented in eqn [3]. The main limitation of this approach is that it cannot discern whether or not the higher levels of use by those with higher levels of need adequately meets their relative need when compared with the healthy; hence the condition described by eqn [7] is at best a necessary but not a sufficient condition for vertical equity. Moreover, it is not possible to measure the extent of vertical inequity using this approach.

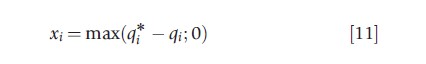

Approach 4: The Effect Of Socioeconomic Status On Healthcare Use At Different Level Of Needs

This approach assumes that vertical equity is identified by differences in the impact of nonneed variables on healthcare use in groups with different needs. One approach that has been used is to explore whether or not nonneed variables affect healthcare delivery at different levels of health. This is achieved by the interaction between need and nonneed variables, for example, by extending eqn [6] to

![]()

In this approach, there is said to be vertical equity if β>0 and σ=0. An alternative approach would be to run separate models for groups with different levels of nonneed variables and testing if the impact (β) of the need variables on healthcare delivery is the same for every group. This is a test for vertical equity because differences in healthcare delivery between groups with different levels of need cannot be regarded as appropriate as long as they are affected by differences in nonneed characteristics, such as income. An extension to this approach involves including an additional condition that in order to meet the vertical equity principle, the response of utilization to need in every SES group should be the same as that observed in a predefined reference group, which is thought to be (more) vertically equitable.

This approach to measuring vertical inequity is problematic because it has also been proposed in the literature as a means of testing for horizontal inequity, on the grounds that, for example, if sick individuals when they are rich receive more health care than the sick when they are poor, the horizontal equity principle is not met. Significant interactions between need and nonneed variables cannot be separated into horizontal and vertical aspects, so this approach cannot be used to test for either vertical equity or horizontal equity in isolation.

Approach 5: Health Outcomes Derived From Unequal Treatment Across Nonneed Groups

This approach assumes that vertical equity is identified by a significant association between healthcare use and a nonneed indicator, but with the same health outcomes in different nonneed groups. The idea behind the approach is that there is vertically equity if different groups, defined in terms of one or more nonneed variable, receive different levels of healthcare delivery and so are treated unequally, but achieve the same health outcomes. In the general framework, where Hi stands for the health outcome of individual i:

![]()

the delivery of health care is considered to be vertically equitable if δ0≠0 in eqn [9], and δ1=0 in eqn [10]; therefore, different SES groups are treated differently, but their outcomes are the same.

One limitation of this approach is that differences in health outcomes are assumed to be a result of differences in the treatment received. There may be a range of reasons why individuals receiving different treatment end up having same health outcomes that do not relate to their treatment but to other factors such as inefficiencies in the provision of health care or to nonhealth-care factors, for example, other social determinants of health. This could be tested directly by including q as an additional covariate on the right hand side of eqn [10]. In addition, and similarly to previous methods, this method is not able to quantify the extent of vertical inequity.

Approach 6: Comparing The Actual Effect Of Need Indicators On Use With The Target Effect Of Need Indicators

This approach assumes that vertical equity is identified by need variables having the appropriate effect on healthcare use. Studies using this approach search for the appropriate effect of the need variables such that individuals with unequal needs receive appropriately unequal treatment. Once the appropriate effects, for example, in terms of regression coefficients, have been derived, they can be compared with the actual effects in order to assess whether the allocation was vertically equitable. Therefore, based on a model such as the one described in eqn [6], this approach tests whether or not the estimated effect of the need variables on healthcare delivery equals the target effect, i.e., if β=β*, where β* is the target effect of the need variable.

Approaches to identifying values of β*could include eliciting society’s preference, calculating the actual effect of the need variables on healthcare delivery in different subgroups of the population, and using the largest value as the target effect.

This approach provides the basis for a test of vertical inequity as described by Gravelle et al. (2006) in eqn [3]. However, it is not capable of measuring the extent of vertical equity. It therefore precludes the quantification of inequity over time and/or between areas and does not assist in monitoring efforts to reduce vertical inequity.

Approach 7: Healthcare Gap Between Actual And Target Health Care

This approach assumes that vertical equity is identified by the distribution of healthcare gaps (HCG), which are defined as the distance between the target level of healthcare delivery and the actual level of healthcare delivery. The target level of healthcare delivery might be exogenously set by policy makers as the minimum level of healthcare delivery that individuals or areas should receive given their levels of need. For example, HCGs x for each individual i are given by:

where, qi* is target healthcare use and qi is actual healthcare use. X=0 when q≥q* , i.e., the HCG has a zero value when individuals receive more health care than the targeted level (the focus of the analysis needs to be reversed to consider the distribution of individuals receiving more than targeted level of health care). The HCGs can be combined across individuals or areas, for example, using poverty indices or standard inequality measures, making value judgments regarding the relative weight of the HCGs in different groups, to provide an aggregate measure of deviations from target levels of healthcare delivery.

The main limitation of this approach, in terms of measuring vertical inequity, is that it is not capable of disentangling horizontal and vertical inequity aspects because the difference between the target level of healthcare delivery and the actual level is affected by deviations from both vertical and horizontal inequity principles. Moreover, this measure only captures healthcare inequity among individuals receiving less than the target level of health care unless we reverse the focus and consider individuals receiving more than the target level. This implies that situations in which individuals receive more than their target level of health care would not be deemed inequitable. Therefore, it is not possible to derive a measure that considers both sides simultaneously and provide a meaningful estimate of the extent and direction of inequity.

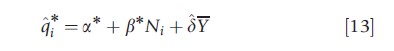

Approach 8: Measuring The Difference Between Target And Need-Expected Healthcare Delivery Across Socioeconomic Status

This approach assumes that vertical equity is identified and measured by the difference between the distribution of the target and the need-predicted health care use with respect to SES. The approach applies similar methods to those now widely used to measure horizontal inequity using concentration indices. Let qi denote the predicted value of healthcare delivery from eqn [6] based on the estimated effect of the need variables (β); and qi* the predicted values of healthcare delivery based on the target effect of the need variables (β*), however defined. In both equations, SES is set equal to the mean value Y in order to neutralize its effect (as a nonneed variable) in the prediction.

![]()

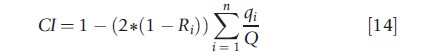

Equation [12] gives the need-expected (also referred to as need-predicted) allocation of health care; eqn [13] gives the target allocation of health care based on the optimal effect of the need variables and the intercept; a*, β*. Sutton (2002) has proposed this methodology to measure the extent to which the gap between the target and the need-expected allocation falls disproportionally on specific SES groups. The target allocation of health care is created by imposing across the whole need distribution the (strictly positive) level of β found in the subpopulation with the lowest levels of need. The method involves computing the concentration index (CI) of the need-predicted and target allocation of health care with respect to SES. The estimate of vertical inequity is the difference between the two. Following Wagstaff (2002), the formula for the CI of socioeconomic inequality can be written as follows:

where Q is the total healthcare use across the sample and Ri = i/n is the fractional rank in the income distribution of the ith person, with i=1 for the poorest and i=n for the richest. Therefore, the CI is one minus the weighted sum of the share of the healthcare variable of each observation, where the weight is given by the position of the individual in the SES distribution of that population. The CI provides a summary measure of the magnitude of socioeconomic-related inequality in a health variable of interest, and by comparing a set of indices one can derive a clearer ranking when trying to compare inequality across a number of countries, regions or time periods.

Vertical equity is then measured as the difference between the CI of the need-predicted healthcare allocation and the CI of the target allocation, i.e., the divergence in the allocation of health care that relates only to the difference between the actual effect and the appropriate effect of the need variables:

These methods control for nonneed indicators in order to appropriately separate the effect of need factors; they provide the comparison between the actual and the target effect of the need variables; and, in particular, they allow for the measurement of vertical inequity by looking at the distributional consequences across the income distribution. However, the focus of this approach is on the measurement of socioeconomicrelated vertical equity in healthcare delivery, which although of interest, may be only part of the vertical inequity which is present in a healthcare system. The reason for this is that vertical inequity arises when individuals with unequal needs do not receive appropriately unequal treatment, and this definition does not rely on the inequity being identified with respect to the socioeconomic dimension solely. Thus, this approach measures what Gravelle et al. (2006) described as the consequences of vertical equity for the groups identified by horizontal inequity, i.e., across the socioeconomic distribution.

As mentioned above, Sutton (2002) derived the target allocation by imposing the value of β found in one part of the health distribution (among the healthy) on to respondents across the whole health distribution. This assumes that the relationship between changes in ill-health and changes in use among the unhealthy ought to be the same as this relationship among the healthy. The underlying requirement for choosing this target was that the effect of the need variable ought to be positive across the full range of the health distribution. The imposition of a strictly positive effect of need on utilization may not be appropriate for specific types of services or patients.

Adapting Measures Used In Other Fields

Approaches to measuring vertical equity have also been considered in other fields, including: healthcare financing; poverty alleviation programs; the transport sector; aid allocation; and, education funding programs.

Most of these methods are of limited usefulness for measuring vertical equity in the delivery of health care. In the case of poverty alleviation programs, transport sector policies and part of the methodology for measuring vertical inequity in finance, the focus is on relative measures, assessing whether or not a variable was redistributed in a more or less vertically equitable way following a policy change. These methods could be applied to assess the relative impact of policies to reduce vertical inequity in healthcare delivery, but do not provide a static measure. A potential difficulty with adapting these approaches to our context is that they require an assessment of the extent to which a particular healthcare policy contributes to the observed redistribution of healthcare delivery.

There are two measures that could be used to capture vertical equity in healthcare delivery – Kakwani’s progressivity index and the ratio of the estimated coefficient to the optimal coefficient of the need indicator. The details of these approaches are summarized in Table 1. Kakwani’s progressivity index, which is widely used in the tax and healthcare finance literature, focuses on the measurement of how far health care is financed according to ability to pay. It is defined as the difference between the CI of payments with respect to income, and the Gini coefficient for prepayment income:

![]()

where the CI is defined as in eqn [14], but now qi represents healthcare payments and Ri is the fractional rank in the prepayment income distribution of the ith person. The Gini coefficient G is analogous to this index where qi stands for the prepayment income. The Kakwani index equals zero if payments as a proportion of income are constant across the income distribution; if payments as a proportion of income increase with income, the index is positive, and the finance source is considered to be vertically equitable or progressive.

This index could be used to measure the extent to which healthcare delivery as a proportion of need increases with needs. However, it could only discern whether or not healthcare delivery is ‘progressive.’ It is not capable of assessing whether the system is ‘responsive enough’ or whether it ‘overmeets’ the needs of the population being served. In this sense, it is similar to Approach 3 described above, with the same limitations.

Applying Toutkoushian’s and Michael’s (2007) method developed for the context of school funding, vertical equity in healthcare delivery could be measured as the ratio of the estimated coefficient, β, to the optimal coefficient of the need factors, β*, in healthcare utilization equations, such as eqns [12] and [13]. Vertical equity would be achieved when VE defined below equals 100%.

Toutkoushian and Michael do not provide a method for estimating the target effect of the need variables, other than suggesting (in an education funding context) to use the monetary amounts prescribed by the state’s foundation program in the setting of per pupil revenues. In the context of the delivery of health care, this would be similar to obtaining policy makers’ or medical experts’ opinion about how health service use ought to increase with needs. If this information were available, this method would permit a summary in one measure of how far the estimated coefficient is from the optimal effect. The ratio could also be compared over time and across different geographies. As with Approach 6 described above, this ratio does not measure the redistributive impact of the difference between the estimated and target allocation across the whole distribution, because it is focused on only what happens on average in a population.

Conclusions And Implications

In this article, different approaches to measuring vertical equity in healthcare delivery have been described. At the outset, it has been noted that although vertical equity considerations seem to be gaining momentum in the context of addressing inequalities and inequities in health and health care, vertical inequity analysis are rarely undertaken. Therefore, existing techniques to investigate vertical inequity have been appraised and assessed, and areas suitable for further work have been identified.

Methods were classified into different approaches and the validity of each was assessed. Approaches used to measure vertical equity outside the field of healthcare delivery were also explored, though none of these approaches was considered to provide any advantage over the methods already used in the field.

Of all the methods considered, Sutton’s (2002) approach using CI techniques was found to provide the most comprehensive analysis of vertical equity in the delivery of health care. However, this approach was developed to measure socioeconomic-related vertical equity only. Emphasis on the socioeconomic dimension of inequity has been the norm in the analyses of horizontal inequity in health care, which is appropriate given that the aim is usually to identify systematic variations in the treatment of those with equal needs but are from different socioeconomic backgrounds. However, in the context of vertical inequity, this approach is possibly rather restrictive. Vertical inequity arises when healthcare delivery is not allocated appropriately according to differences in needs. This definition therefore does not require inequity to be measured with respect to a socioeconomic dimension, but emphasizes the need dimension. Further work is necessary to extend this methodology for ensuring that the consequences across the need distribution have been accounted for. This could be accomplished, for example, by computing the concentration indices with respect to the needs variable rather than with respect to SES.

Quantifying the extent to which healthcare delivery ought to vary at different levels of needs is a major challenge when investigating vertical inequity. In the absence of information from policy makers regarding how much more high need individuals ought to receive as compared with those with lower needs, the literature on vertical equity has suggested different approaches. These include asking the community, identifying areas within a country that are more responsive to the needs of their populations, and imposing the positive effect of ill-health on use as found in one part of the health distribution (where the effect has been found to be strictly positive) onto respondents across the whole health distribution. One alternative approach could involve using external evidence regarding subgroups of the population more likely to achieve a vertically equitable allocation (i.e., subgroups more likely to receive the health care they ought to, given their needs, or geographical areas where performance indicators suggest an allocation of resources that align resources appropriately with needs). Another alternative could be to identify the use of services for a set of clearly defined needs that are based, for example, on clinical guidelines for a particular medical condition. This may be of limited use, especially for studies looking at vertical inequity across healthcare services generally, but could be appropriate if considering a specific service.

In conclusion, the importance of incorporating vertical equity considerations in the way healthcare resources are allocated is being increasingly emphasized. The few empirical studies that have investigated vertical equity in healthcare delivery have used a variety of methods with different underlying assumptions. In this article, some light has been shed on the differences and the validity of the approaches being used has been discussed. Also, areas for further work have been highlighted with a view to improving methods for measuring vertical equity in the delivery of health care.

References:

- Gravelle, H., Morris, S. and Sutton, M. (2006). Economic studies of equity in the consumption of health care. In Jones, A. (ed.) The Elgar companion to health economics, pp 193–204. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Marmot, M. (2010). Fair society, healthy lives: The Marmot review. London: University College London.

- Sutton, M. (2002). Vertical and horizontal aspects of socio-economic inequity in general practitioner contacts in Scotland. Health Economics 11, 537–549.

- Toutkoushian, R. K. and Michael, R. S. (2007). An alternative approach to measuring horizontal and vertical equity in school funding. Journal of Education Finance 32, 395–421.

- Wagstaff, A. (2002). Inequality aversion, health inequalities and health achievement. Journal of Health Economics 21, 627–641.

- Abasolo, I., Manning, R. and Jones, A. M. (2001). Equity in utilization of and access to public-sector GPs in Spain. Applied Economics 33, 349–364.

- Alberts, J. F., Sanderman, R., Eimers, J. M. and Van Den Heuvel, W. J. A. (1997). Socioeconomic inequity in health care: A study of services utilization in Curacao. Social Science and Medicine 45, 262–270.

- Laudicella, M., Cookson, R., Jones, M. J. and Rice, N. (2009). Health care deprivation profiles in the measurement of inequality and inequity: An application to GP fundholding in the English NHS. Journal of Health Economics 28, 1048–1061.

- Raine, R., Goldfrad, C., Rowan, K. and Black, N. (2002). Influence of patient gender on admission to intensive care. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 56, 418–423.

- Raine, R., Hutchings, A. and Black, N. (2004). Is publicly funded health care really distributed according to need? The example of cardiac rehabilitation in the UK. Health policy 67, 227–235.

- Rocha, G. M. N., Martınez, A. M. S., Rıos, E. V. and Elizondo, M. E. G. (2004). Resource allocation equity in northeastern Mexico. Health Policy 70, 271–279.

- Sutton, M. (2002). Vertical and horizontal aspects of socio-economic inequity in general practitioner contacts in Scotland. Health Economics 11, 537–549.

- Sutton, M. and Lock, P. (2000). Regional differences in health care delivery: Implications for a national resource allocation formula. Health Economics 9, 547–559.