Introduction

Until the seventeenth century, world population behavior was governed by a straightforward Malthusian mechanism: sporadic technical advances and favorable climatic conditions reduced mortality via relaxation of the constraints imposed by the supply of goods; these would then lead to increased population, which would then reverse the movement, bringing standards of living back to the limits of simple reproduction. Mortality rates had great variability with no clear trend and, by the Year 1600, life expectancy was probably about the same as it had been 2000 years before. These Malthusian responses following positive permanent shocks explain a timid but persistent population growth, despite the trendless behaviors of mortality and fertility rates.

This pattern started to break down for some Western European and Scandinavian countries in the eighteenth century. Mortality rates fell (life expectancies increased) without any indication that a countervailing Malthusian mechanism was at work. Population growth for these countries increased, reaching a peak in the mid-nineteenth century, after which, as a consequence of fertility declines, growth rates started coming down. This pattern was followed closely by, among others, the United States and Canada and, by the beginning of the twentieth century, this group of countries had populations larger than they ever had before, together with health and life expectancy levels unprecedented in human history.

This transformation marked the onset of the demographic transition and was an essential part of the process of economic development that continued spreading unabated through most of the world until today. This revolution, however, took some time to reach the developing countries. It was only after World War I that mortality levels began to decline in the poorer regions of the world. Nevertheless, in these areas, the process took place at a much faster pace and at much lower income levels than it had in Europe and North America. Renewed and persistent mortality reductions throughout most developing regions after World War II changed the face of human societies and led to the population explosion observed during the twentieth century.

These health improvements played a central role in the history of population growth. A strand of theoretical literature also argues that they were a potentially important force determining the reductions in fertility observed at later stages of the demographic transition, as well as the increases in human capital and growth registered thereafter. Nonetheless, the precise causes of the improvements in health and reductions in mortality in the developing world are not yet entirely understood.

In this article, the available evidence on the determinants of health and mortality in developing world is reviewed. The next Section Patterns of Health and Mortality starts with a discussion of some historical patterns and aggregate studies. Following that, the results from a vast array of studies analyzing various dimensions of potential determinants of health and mortality are summarized. Finally, the Section Discussion concludes with a synthesis of what is known up to now and some general remarks.

Patterns Of Health And Mortality In The Developing World

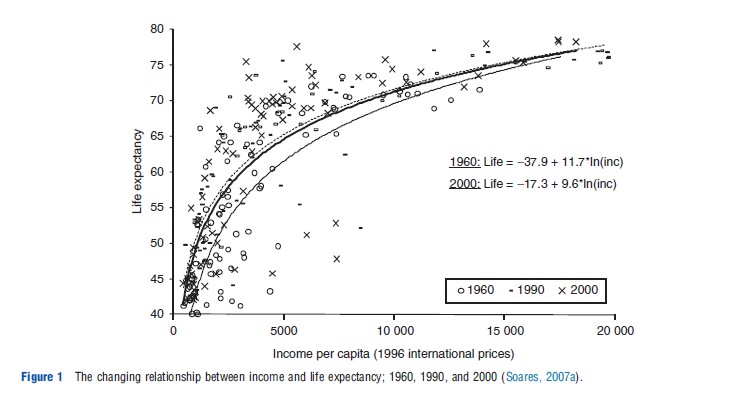

Perhaps the most striking feature of the improvements in health in the developing world is how they became increasingly dissociated from gains in income or overall improvements in individual living conditions. This is most clearly seen in the so-called Preston curve, which portrays the relationship between income per capita and life expectancy across countries. Figure 1 reproduces this curve for the years 1960, 1990, and 2000. There is a positive correlation – close to logarithmic – between income per capita and life expectancy at each point in time. But this relationship has been shifting since the beginning of the twentieth century. This pattern was first noticed by Samuel Preston, who compared data between 1930 and 1960, and has persisted through several decades. In other words, countries at a given income level in 2000 experienced much higher life expectancies than countries at comparable income levels in 1960. From a historical perspective, this amounts to saying that a significant fraction of the gains in life expectancy over the last century were unrelated to changes in income.

In addition, these gains have been particularly strong for countries at lower income levels. This pattern led to reductions in life expectancy inequality in the postwar period: by any measure, inequality in life expectancy declined substantially after 1960, apart from a mild increase after 1990 due to the arrival of HIV/AIDS. Despite different patterns of access to water, sanitation, education, income, and housing in developing countries, there was a surprising stability and homogeneity in this process of mortality reduction in the postwar period.

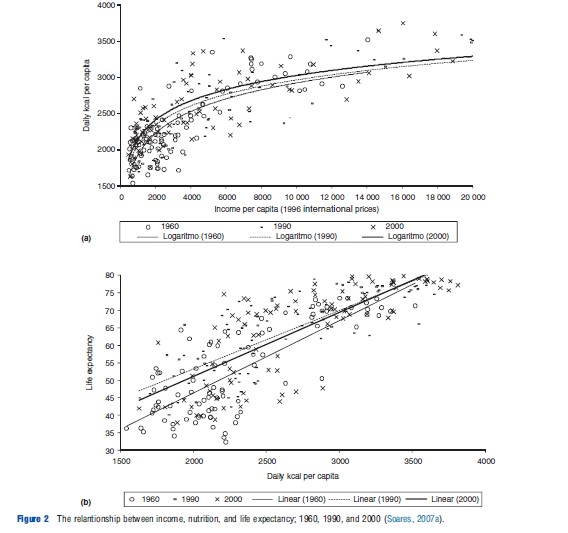

The evidence also shows that the shift of the Preston curve is not an artifact of a falling price of food and improved nutrition at constant levels of income. Preston classifies countries in different nutrition and income brackets and compares data from 1940 and 1970. He shows that life expectancy gains took place at constant levels of income and nutrition. Even for the lowest nutrition group (o2100 cal daily), he identifies an increase of 10 years in life expectancy at birth.

Figure 2 shows the same pattern. At constant levels of income, nutrition does seem to have improved slightly between 1960 and 2000. This may be the result of technological improvements and declines in the relative price of food. Nevertheless, it is far from enough to explain the shift in the income–life expectancy profile: the cross-sectional relationship between nutrition and life expectancy at birth shifted in much the same way as the cross-sectional relationship between income and life expectancy. Between 1960 and 1990, at constant nutritional levels, life expectancy at birth rose by as much as 8 years. In a cross-country econometric analysis relating life expectancy improvements to income and caloric consumption, Preston concludes that approximately 50% of the changes in life expectancy between 1940 and 1970 were due to ‘structural factors,’ unrelated to economic development or nutrition. Other research finds similar results for the period between 1960 and 2000.

The evidence also suggests that this is not an artificial result due to aggregation and within country changes in the distributions of these variables. In the case of Brazil, for example, municipality-level data between 1970 and 2000 show a within country shift in the cross-sectional relationship between income and life expectancy that is similar to that observed across countries. At constant levels of income, life expectancy typically rose by more than 5 years, meaning that at least 55% of the improvements in life expectancy in Brazil during these 30 years seemed to be unrelated to gains in income per capita. Similar evidence is also available for Mexican states.

Analogous conclusions were generated by other studies in very different settings. Mortality changes in Latin America between 1950 and 1990 show that mortality does respond to short-term economic crisis but that these responses are very small and quantitatively irrelevant when compared with historical changes (though morbidity changes may be substantial). The classic concept of ‘mortality breakthroughs’ itself was based on historical experiences of improvements in health that were not related to growth in income per capita. Several other researchers present various arguments and evidence indicating that the relationship between income, nutrition, and mortality is far from enough to explain the improvements in health and life expectancy observed during the twentieth century.

The question remains, therefore, as to what were the factors that determined these improvements in health, mostly independently of individual standards of living. Further insight in this matter can be obtained by looking into the profile of changes in the distribution of mortality by age and cause of death. This pattern of changes in the age and causedistribution of mortality is usually referred to as the ‘epidemiological transition,’ a term first coined by Abdel Omran. It describes the process of change in leading causes of death, from infectious diseases to chronic nontransmissible diseases, that takes place as mortality reductions progress. There is also an accompanying shift in the age distribution of deaths, from younger to older ages, until child and infant mortalities converge to close to zero.

There is a wealth of information on the epidemiological transition experience of some developed countries. For the nineteenth century US, for example, infectious diseases were responsible for 45% of all deaths between the ages 0 and 4 years, with birth-related and childhood diseases accounting for an additional 30%. Improvements in the period were driven mainly by the acceptance of the germ theory, leading to the boiling of milk and sterilization of bottles, hand washing, isolation of the sick, etc. During the first half of the twentieth century, infectious diseases were still the leading cause of death, and nutrition and public-health infrastructure were the main determinants of improvements in health (reduced deaths from infectious diseases were responsible for three-quarter of the gains in life expectancy in the period). Between 1940 and 1960, infectious diseases continued to play a role, but medical innovations (antibiotics) became increasingly more important (health improvements concentrated on diseases for which new drugs became available). Finally, after1960, mortality reductions shifted toward more sophisticated and technologically intensive medical advances, concentrated at old ages and on conditions such as heart and circulatory diseases.

The historical evidence from England shows a similar pattern. A relatively small number of infectious diseases account for the entire improvement in life expectancy observed in England and Wales between 1837 and 1900. Some interpretations argue that changes in nutrition were the main determinant of changes in susceptibility to these diseases, but others give more credit to public policy (mainly sanitary reforms, perhaps responsible for 25% of the reductions in mortality in the period). Infectious diseases accounted for 68% of the overall reductions in mortality in England up to the 1950s.

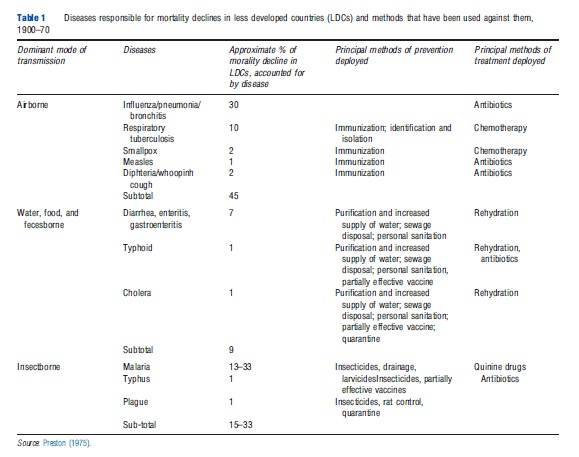

A similar path was followed by developing countries in the second half of the twentieth century. Preston was the first to try to map the reductions in mortality in the developing world between 1900 and 1970 into different causes of death. Table 1 presents the approximate fraction of mortality reductions in less-developed countries accounted for by different diseases. Preston argues that preventive measures associated with public-health programs and infrastructure were probably the main determinants of the changes portrayed in the table (apart from the case of influenza, pneumonia, and bronchitis). Large-scale immunization, cleaning of water systems, and sewage disposal are examples of changes that took place in several less developed countries throughout the period. This interpretation would suggest that approximately 50% of the life expectancy gains in the period were unrelated to simple improvements in material conditions.

Evidence for Latin America between 1955 and 1973 suggests that dimensions unrelated to living standards were more important in regions where malaria was endemic, and where other infectious diseases were more prevalent. According to this view, approximately 55% of the reductions in mortality would be attributable to factors not directly linked to improvements in living conditions.

The discussion from the previous paragraphs hints at a relationship between mortality by cause of death and available methods of prevention and treatment. Similarly, mortality by cause of death is intimately linked to mortality by age, and to the stage of a specific society in the process of epidemiological transition. At a given historical moment, both of these are associated with the health technologies available and employed in each particular case. For these reasons, the historical profile observed in developed countries is analogous to the cross-country gradient observed in the postwar period. Analogously, mortality reductions experienced by developing regions in the past 40 years, for example, are very similar to those experienced by the US in the beginning of the twentieth century.

The pattern of cause and age-specific life expectancy gains across different development levels between 1965 and 1995 illustrates this point. In poorer regions (Middle East and North Africa), life expectancy gains are almost entirely concentrated on infectious diseases of the respiratory and digestive tract, and congenital anomalies and perinatal period conditions. As a result, 90% of the mortality reductions are concentrated at younger ages. As the development level increases, mortality shifts continuously from early to old ages (following, in sequence, Latin America and the Caribbean, East Asia and the Pacific, Europe and Central Asia, and North America). For the most developed regions, 60% of the life expectancy gains are due to heart and circulatory diseases and nervous systems and senses organs conditions, all concentrated in old ages.

Historical trends and cross-country profiles within countries suggest a specific process of health improvements and mortality reductions. This process mimics the movement of a country through the different stages of the epidemiological transition. Still, there is no consensus as to the specific factors that determined these improvements in health in each different circumstance. In the next Section Evidence on Determinants of Health Improvements, to shed some light on the issue, the evidence on the determinants of mortality reductions in specific contexts is discussed.

Evidence On Determinants Of Health Improvements In The Developing World

The evidence discussed in the Section Patterns of Health and Mortality suggests that ‘structural factors,’ not directly related to economic development, were responsible for a substantial fraction of the recent reductions in mortality in developing countries. Substantial reductions in mortality were observed at very low income levels and with minimal expenditures on health, so it is believed that diffusion of new technologies must have played a role.

New technologies may come into play as determinants of health through various channels. First, in some dimensions, health is the outcome of household production (personal hygiene, handling and preparation of food, treatment of water, etc.). From this perspective, new technologies are incorporated through absorption of knowledge by individuals. This is probably particularly important at very low levels of development (or high levels of mortality).

Second, some health technologies have a major public good component. Ideas and knowledge are extreme examples of this. Once the germ theory became accepted, for example, its main implications became publicly available to all agents. In more specific health technologies, externalities and traditional public goods are also very important (development of new medicines, water and sewerage systems, vaccination campaigns, environmental regulations, etc.). Sometimes implementation involves large fixed costs and low marginal costs, other times adoption depends on the outcome of a centralized political process. Changes are, to a great extent, outside the control of any individual agent in society and, given its political and technological nature, may be even considered exogenous to the economic conditions faced by a country.

Therefore, the diffusion of health technologies in developing countries over the last century was most likely driven by the absorption of knowledge by agents and public provision, rather than by the same factors determining diffusion of technologies associated with the production of private goods. This is particularly important for changes in mortality observed at low levels of development, when improvements can take place even with minor expenditures on health. This logic points to particular candidates as main determinants of the health improvements discussed in the Section Patterns of Health and Mortality. These are associated with diffusion of pure nonrival and nonexcludable knowledge, public or international interventions related to public-health infrastructure and to particular diseases, and family and community health programs focused on health practices.

Perhaps the clearest example of the role of technology and public good provision is the United Nations’ Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI). The program started in 1974 with the objective of extending worldwide access to vaccines against measles, diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, tuberculosis, and polio, among others. In countries covered, the EPI led to major increases in immunization rates within few years, while infection rates dropped abruptly. Among other things, the program led to virtual eradication of polio from the Americas in 1994, and raised immunization for the six target diseases from 5% of the world’s newborns in 1974 to approximately 80% in 2000.

Another example of a successful intervention against particular conditions is the case of Malaria. In Sri Lanka starting in 1945, dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) became available, leading to the elimination of mortality differentials between endemic and nonendemic areas, and to fast declines in mortality rates. Malaria control contributed with 23% of the observed reduction in death rates up until 1960. From 1946 to 1950, malaria is estimated to have contributed with one-third of the total reduction in mortality. Similar results from other malaria control programs have been documented in countries such as Guyana, Guatemala, Mexico, Venezuela, and Mauritius.

A very important coordinated effort was the World Health Organization (WHO) campaign launched in the 1950s to eradicate malaria. The campaign counted on WHO’s technical support and was partially funded by USAID and UNICEF. It was based mostly on DDT spraying, with the objective of breaking up the transmission of malaria for long enough so that the pathogen would eventually die, coupled with some medical assistance. Analyses of the experiences of Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico indicate that in all three cases the campaign was followed by large declines in malaria prevalence. In Colombia, prevalence rates fell by approximately 80%. Overall, however, for Latin America as a whole, the campaign proved ineffective in eradicating malaria, with partial resurgence observed some decades after the initial intervention. Nonetheless, even in these cases, prevalence was never again comparable to the preintervention levels.

A view sometimes presented as a competing alternative in the demographic literature postulates that focused interventions have limited effects, and that the main driver of good health in developing countries is a set of ‘appropriate’ social and political conditions. This has been argued to be the case, for example, in the three famous experiences of ‘breakthroughs’ in mortality reduction: Kerala (India, 1956–66), Sri Lanka (1946–53), and Costa Rica (1970–80). These three cases were also exceptional in their social and political environments, and in their effectiveness in providing inputs in the areas of education, health services, and nutrition. Female autonomy, open political systems (competition), large civil society without rigid class structure, and national consensus related to policies are highlighted as factors allowing the adoption of health inputs and the absorption of new technologies. In Sri Lanka, cholera was contained in the 1870s through quarantine measures and construction of water systems, whereas neonatal tetanus was cut down by the systematic use of midwives. From 1910 on, successful campaigns against diarrhea, respiratory infections, and hookworm stressed the need for public health, sanitation, and personal hygiene. Other important events included a malaria campaign started immediately after the war (using DDT) and the popularization of penicillin and sulfa (sulphonamide) drugs. Health expenditures were never more than 1.5% of gross domestic product, despite profound improvements in public health. In Kerala, the mortality breakthrough took place between 1956 and 1966, when deaths from cholera and smallpox were drastically reduced. Extensions of public-health programs and immunization – through provision of community level services – are identified as the proximate reasons behind these mortality reductions. Costa Rica, in turn, increased expenditure on health services leading to major health improvements between 1970 and 1980. Easy access to community-level services – coupled with immunization campaigns – were also identified in this case as important factors in the reduction in infant and child mortality. The case of Jamaica (which had life expectancy greater than 75 in 2000) also fits well in the above logic: women were historically more independent, schooling developed early, and there was a tradition of discussion of political issues. In Jamaica, school teachers were trained to be health educators, coaching people on how to recognize and treat themselves against specific diseases and vectors.

The important role of easy access to primary health care and family planning, sometimes combined with other interventions, is highlighted in various studies. Data from 16 years of operation of the International Centre for Diarrheal Disease Research (Matlab Thana, Bangladesh), between 1966 and 1981, provide evidence on the effect of family planning, tetanus vaccine, and oral rehydration therapy. The data suggest that tetanus vaccine (given to pregnant women) reduced newborn 4–14 day mortality by 68%. A broad program of family planning was estimated to be responsible for a 25% reduction in death rates, with rehydration therapy accounting for another 9%.

The Brazilian Family Health Program, implemented in the 1990s and expanded during the 2000s, provides additional evidence on the role of family and community based health interventions. The program was largely based on preventive care, but evidence shows that coverage also affected breastfeeding and immunization, and improved maternal management of diarrhea and respiratory infections. It was particularly effective in improving health at early ages and reducing deaths from perinatal period conditions and infectious diseases, and it was also associated with improved subjective assessments of health status.

The extreme experience of reduction in maternal mortality in Sri Lanka is also an important example. In Sri Lanka between 1946 and 1953, there was a reduction of 70% in maternal mortality rates, from 1.8% to 0.5%. This reduction is thought to have been the consequence of changes in various health policies associated with increased access to health centers, midwives, and hospitals (and possibly also with introduction of sulfa drugs and penicillin).

The historical experience of Cuba is yet another case supporting the role of community and family based interventions. US occupation of the island between 1898 and 1902 initiated a series of sanitary reforms, culminating in the virtual elimination of yellow fever, as well as reductions in mortality from tuberculosis and other infectious and parasitic diseases. In some cases, such as tuberculosis, health improvements seem to have been due to better economic conditions and nutrition, combined with the introduction of antibiotics after the 1940s. Other infectious and parasitic diseases – such as diphtheria, malaria, diarrhea, gastritis, and enteritis – were more directly affected by specific sanitary and public-health measures and efforts to teach proper infant care (supposedly accompanied by improvements in education). Nevertheless, some researchers point out that improvements in education, urbanization and targeted health programs occurred early in the twentieth century, whereas a major fraction of the progress in life expectancy was observed only long after that. Therefore, the authors suggest that the role of easy access to primary health care should be even larger than that initially suggested.

Also in the case of Costa Rica between 1968 and 1973, access to medical care (proportion of births under medical attention) had a substantial impact on child mortality. Still, as it relates to improvements in health overtime, education, and sanitation appear as important driving forces. One study shows that the same trend of health improvement continued in Costa Rica after 1970 and suggests that factors similar to those highlighted in the previous period played a role in this later experience. For rural India, data between 1973 and 1978 show that, together with mothers’ literacy, type of birth attendant and triple vaccination were closely related to regional variations in child mortality. Poverty and medical care received at birth emerged as central for neonatal mortality, whereas availability of medical facilities and immunization coverage were the main correlates for postneonatal mortality.

Public-health infrastructure, combined with education, also appears as an important determinant of health improvements in various other contexts. Sanitation and women’s education were the most important factors determining child mortality differences in Guatemala between 1959 and 1973. For the case of Brazil between 1970 and 2000, education and sanitation were also the key determinants of changes in child mortality, whereas access to clean water, in addition to education and sanitation, appeared as an important determinant of life expectancy at birth.

Access to clean water, again together with women’s education, appears as an important determinant of health outcomes in several papers. This is the case in the experience of Malaysia between 1946 and 1975, where mothers’ education and piped water were the factors most closely associated with child mortality (sanitation also appears as marginally relevant), as well as for Brazil. In particular, data between 1970 and 1976 have been used to track down the effects of a program that targeted the improvement of urban environmental conditions (PLANASA), showing that parents’ education and access to piped water were the factors most closely related to child mortality both in 1970 and 1976 (access to piped water explained one-fifth of regional differentials in child mortality). Some evidence on the importance of water quality comes from the Argentina, where researchers have explored improvements in the quality of water provision following the privatization of local water companies in approximately 30% of Argentina’s municipalities. The results show a reduction of 8% in child mortality (mostly from infectious and parasitic diseases) in areas that had their water services privatized (the reduction increases to 26% in the poorest areas).

The evidence from the historical experience of the US also lends support to the potential role of clean water technologies in developing countries. It was estimated that clean water technologies were responsible for 43% of the reductions in mortality in major American cities during the early-twentieth century. For infant mortality, this share is estimated to rise to 74%, whereas for typhoid fever, clean water is thought to have led to virtual eradication.

For some other dimensions, there is no evidence available from developing countries. In some of these cases, the historical evidence from the developed world may also be informative. Regarding the role of new drugs, for example, there is evidence on the case of the introduction and diffusion of sulfa in the US after 1937. The prevailing view from the literature is that medical innovations played a small role in US mortality declines between 1900 and 1950, but the introduction of sulfa drugs in the mid-1930s represented the development of the first effective treatment of various bacterial infections, including scarlet fever, puerperal sepsis, erysipelas, pneumonia, and meningitis. The available literature suggest that the arrival of sulfa drugs was responsible for declines of 25% in maternal mortality, 13% in mortality from pneumonia and influenza, and 52% in mortality from scarlet fever, amounting to between 40% and 75% of the total decline in mortality from these causes of death during the period. Similarly, the episodes of eradication of hookworm diseases in the American South show how powerful the use of drugs (deworming medicines) coupled with educational campaigns (on how to recognize symptoms) can be. Infection rates among children, which were approximately 40% in 1910, dropped to nearly zero after an intervention sponsored by the Rockefeller Sanitation Commission.

Discussion

The evidence on the determinants of mortality and health in developing countries from the microliterature is very diverse in nature, focus, and methodology. Still, it does reveal some repeated patterns.

First, interventions targeted at particular conditions (malaria, tetanus, diarrhea, large-scale immunizations, etc.) have shown sustained success in improving health and reducing mortality. This debunks the once common argument that narrow approaches focused on specific technologies may end up simply increasing mortality from competing causes of death, and not lead to sustained improvements. The evidence suggests just the opposite: in the case of malaria and measles eradication in Guyana, Kenya, Sri Lanka, Tanzania, and Zaire, the implementation of targeted programs led to reductions in mortality systematically larger than the direct reduction in the cause of death that constituted the initial target. Reductions in mortality from one cause of death, in reality, seem to lead through synergistic links to reductions in mortality also from other causes. This should be expected when one type of disease increases individuals’ susceptibility to infections and other diseases (due to weakened immune system or reduced capacity to absorb nutrients).

Still, family health programs and other broad-based community interventions, taking into account the scope of social specificities of local populations, also seem potentially relevant. This was the case with successful programs implemented in Bangladesh and Brazil, and also with some dimensions of the Jamaican experience. Disease-specific targeted interventions and broad programs focused on health practices and the cultural context, rather than being mutually exclusive alternatives to explain health improvements in the developing world, are likely to be both relevant in explaining the diversity of experiences observed. The ideal program in each particular case seems to be a function of the incidence of endemic conditions for which specific interventions are available, as compared to the incidence of conditions that can be minimized through improvements in individual or collective health practices.

Second, in relation to the role played by specific factors, there is an overwhelming amount of suggestive evidence pointing to the importance of education as a determinant of child health. Part of this relationship reflects the effect of income on health, but studies controlling for socioeconomic status still found robust correlations between mother’s education and child mortality. Irrespectively, even if taken as causal, this relationship is not yet fully understood in the literature. Some suggest that parental education leads to more use of medical care and sanitary precautions, better understanding of nutritional information, and better recognition of serious health conditions. One study, for example, shows that mothers’ literacy is associated with type of medical care during birth and in the postneonatal period. Still, the effect of parental schooling may be more related to modernization and indoctrination. Schooling could be a mechanism to familiarize the population with modern values, reducing resistance to formal medical attention and medicines. A review of a vast array of evidence concludes that educated mothers are better informed about and more likely to use medical facilities and other health technologies, are more likely to have their children immunized and to have received prenatal care, and are more likely to have their deliveries attended by trained personnel. At the same time, the social aspects in the relationship between education and child mortality were also present: educated mothers marry later, tend to have fewer children, and to invest more in each child. Overall, the following channels linking mother’s education to child mortality were identified: greater cleanliness, increased utilization of health services, greater emphasis on child quality, and enhanced female empowerment.

The role attributed to public-health infrastructure can be analyzed through the results related to access to clean water and sanitation. Some microstudies emphasize one of these dimensions in detriment of the other, maybe due to the high correlation between them, and few papers have been able to identify independent effects of each. But many of the analyses discussed here find a significant correlation between either sanitation, or access to clean water, and health (in most cases, mortality). Anecdotal evidence from Cuba and Kerala, among others, also supports the potential importance of factors linked to public-health infrastructure in triggering sustained improvements in health.

From a broad perspective, the evidence does not point to one specific factor as the main determinant of health status and mortality in developing countries. There is strong evidence on the success of targeted interventions in some contexts, such as malaria control, rehydration therapy, and immunization, whereas there are also various qualitative and quantitative studies indicating that family and community health programs can be effective, by reducing the probability of infections and improving health management. Finally, there is also evidence on importance of health infrastructure, through access to clean water and sanitation. Based on the evidence currently available, it is still impossible to isolate the specific role of each of these factors, or to identify their relative importance in different contexts. These would be important goals for future research in the area.

Bibliography:

- Preston, S. H. (1980). Causes and consequences of mortality declines in less developed countries during the twentieth century. In Easterlin, R. S. (ed.) Population and economic change in developing countries, pp. 289–341. Chicago: National Bureau of Economic Research, The University of Chicago Press.

- Preston, S. H. (1975). The changing relation between mortality and level of economic development. Population Studies 29(2), 231–248.

- Soares, R. R. (2007a). On the determinants of mortality reductions in the developing world. Population and Development Review 33(2), 247–287.

- Becker, G. S., Philipson, T. J. and Soares, R. R. (2005). The quantity and quality of life and the evolution of world inequality. American Economic Review 95(1), 277–291.

- Caldwell, J. C. (1986). Routes to low mortality in poor countries. Population and Development Review 12(2), 171–220.

- Fogel, R. W. (2004). The escape from hunger and premature death, 1700–2100 – Europe, America, and the third World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 191 p.

- Hill, K. and Pebley, A. R. (1989). Child mortality in the developing world. Population and Development Review 15(4), 657–687.

- Hobcraft, J. (1993). Women’s education, child welfare and child survival: A review of the evidence. Health Transition Review 3(2), 159–173.

- Livi-Bacci, M. (2001). A concise history of world population, 3rd ed. 251 p. Malden: Blackwell Publishers.

- Omran, A. (1971). The epidemiological transition: a theory of the epidemiology of population change. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly 49, 509–538.

- de Quadros, C. C. A., Marc Olive´, J., Nogueira, C., Carrasco, P. and Silveira, C. (1998). Expanded program on immunization. In Benguigui, Y., Land, S., Mar´ıa Paganini, J. and Yunes, J. (eds.) Maternal and child health activities at the local level: Toward the goals of the world summit for children 1998, pp. 141–170. Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization.

- Riley, J. C. (2001). Rising life expectancy – A global history. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Riley, J. C. (2005b). Poverty and life expectancy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.