Introduction

Public expenditure targets, inflation, tax policy, and exchange rates, among other factors, will have effects on the provision of health care and the health status of the population. For instance, national income and fiscal targets will constrain how much a government can spend on health care, the exchange rate will be a factor determining the cost of vaccines and drugs, and tax policies relating to tobacco, alcohol, and ‘fast food’ will influence people’s demand for these products and ultimately their health. Conversely, of course, the health of a population can significantly influence macroeconomics, affecting a country’s rate of economic growth for example.

Macroeconomics, which encompasses these and other factors, is thus increasingly important for health and health care, especially as economies become more integrated in international trade and financial systems. This article outlines the key concepts within macroeconomics, and their application with respect to health and health care.

What Is ‘Macroeconomics’?

Economics is broadly divided into microeconomics and macroeconomics. Microeconomics is essentially concerned with choices and activities at the individual or firm level. It is concerned with what goods firms decide to produce and what goods households decide to consume. The interaction of households and firms takes place within a market, where price movements seek to equate demand and supply. Typically these markets are combined to form what are termed ‘sectors,’ such as agriculture, manufacturing, or health care. Together the interaction of these sectors comprises ‘the economy.’ Macroeconomics is then concerned with choice and activities across a number of these markets and sectors, and thus ‘the economy’ as a whole. In doing so, a whole set of terminology different to microeconomics is found, the main ones outlined in the glossary in Box 1.

International Trade

An important element of macroeconomics is international trade. According to the ‘law of comparative advantage,’ free trade (i.e., exchange of goods) between countries encourages countries to produce the goods that they are best placed to produce compared with other countries. A comparative advantage exists when an individual, firm, or country can produce a good or service with less forgone output (opportunity cost) than another. This differs subtly from ‘absolute advantage’; for instance, where a country with lots of sunshine and wide open spaces could be seen to have an absolute advantage in agriculture compared to a country with little sunshine and mountains. Thus, call centers are increasingly located in countries such as India, not because their location there involves fewer inputs for any given number of calls or because wages are lower than elsewhere (which would confer an absolute advantage), but because the lost output from using people in this way rather than another way is smaller than it would be in, say, most European countries or North America. Conversely, research-based industries, like innovative pharmaceutical firms, are located mainly in high-income countries despite their relatively high wage levels because they too have a comparative advantage. Clearly, some countries may have an absolute advantage in producing nearly everything, but it is impossible for them to have a comparative advantage in everything. Conversely, some countries have an absolute advantage in virtually nothing, but they too necessarily have a comparative advantage in something. Given certain assumptions, total world production will therefore increase, and consumption possibilities increase, if countries specialize according to their comparative advantage and trade these goods with each other. Those countries that engage in trade will therefore see increasing gross domestic product (GDP), a wider selection of available goods and services, higher employment, and higher government revenues (due to higher income).

The problem of course is that, in practice, many countries create barriers to trade to ‘protect’ domestic industries, including tariffs, import restrictions, and bans. The effect of such protection is that it enables countries to continue to produce goods in which they have no comparative advantage, but at the same time discourages those countries who do actually hold the comparative advantage in such products. Why would a country do this? Typically this is specific political lobbying by an industry/sector or relates to an area deemed important for national security. However, the period since World War II has seen significant initiatives targeted to increase free trade, and has witnessed unprecedented increases in global trade activity.

How Does Macroeconomics Relate To Health And Health Care?

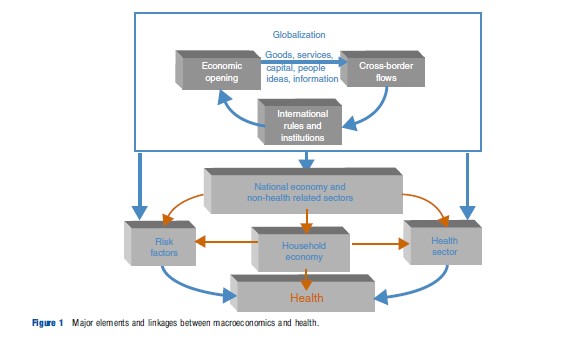

In this article, the term macroeconomics is used to refer to consideration of issues that fall outside of the health (care) sector. Thus it is not concerned with the inner workings of the health sector – such as how doctors are paid, or the cost-effectiveness of alternative screening programs – but the wider interactions between health and economy, health versus other sectors, and trade impacts on health. In this respect, there are a range of proximal and distal linkages between macroeconomics and health; illustrated in Figure 1. The lower half of the figure represents the individual country under consideration, and the upper half the aspects of the international system. The arrows between the various components indicate the major linkages. This is a deliberately simplified picture to provide a concise and understandable frame of reference.

Taking the lower half of the figure first, what may be termed as the ‘standard’ influences on health are illustrated. These include risk factors, representing genetic predisposition to disease, environmental influences, and infectious disease. Next is the household, which represents factors associated with how people behave and, crucially, invest in their health. There is then the health sector, which comprises those goods and services consumed principally to improve health status. Finally, encompassing all these, there is the national economy, representing the metainfluences of government structures and other sectors.

In the upper half of the figure, the influences of factors that are usually outside national government jurisdictions are illustrated. For example, there is a wide variety of international influences directly upon risk factors for health, including an increased exposure to infectious disease through cross-border transmission of communicable diseases, marketing of unhealthy products and behaviors, and environmental degradation. Increased interaction in the global economic system will also affect health through influences upon the national economy and wealth. It is well established, for instance, that economic prosperity is ‘generally’ positively associated with increased life expectancy. Finally, health care will be affected through the direct provision and distribution of health-related goods, services, and people, such as access to pharmaceutical products, health-related knowledge and technology (e.g., new genomic developments), and the movement of patients and professionals. Also note that in this upper half of the figure, the importance of international legal and political frameworks that underpin much of these activities, such as bilateral, regional and multilateral trade agreements is seen.

In terms of linkages between these influences, increased macroeconomic trade will bring associated changes in risk factors for disease. These will include both communicable diseases, as trade encourages people and goods to cross borders, and noncommunicable diseases, as changes in the patterns of food consumption, for instance, are influenced by changes in income and industry advertising. Increased macrolevel interaction will also impact upon the domestic economy through changes in income and the distribution of that income, as well as influencing tax receipts. This will influence the household economy and also the ability of the government to be engaged in public finance and/or provision of health care. Finally, there will be direct interactions in terms of health-related goods and services, such as pharmaceuticals and associated technologies, health care workers, and patients. Let us explore these in a little more detail.

Macroeconomics And The Household

Macroeconomic policy is concerned with economic growth – increasing levels of GDP – as higher GDP leads to greater opportunities to consume which will, ceteris paribus, improve health (although it may not!). The relevant factors in this relationship are improved nutrition, sanitation, water, and education. In this respect, engaging in global macroeconomic integration – or international trade – is a key factor leading to economic growth through specialization. However, although trade liberalization may be poverty-alleviating in the long run, at least in the short term it is often the adverse consequences, particularly to the most poor, that are observed (e.g., increased cost of living, development of urban slums, chronic disease, pollution, and exploitative and unsafe work conditions) and lead to significant ill-health.

One of the criticisms of conventional macroeconomic approaches is the inadequate attention paid to distributional impacts – most are generally based on the aggregate indicators such as ‘total’ income, trade volume, employment, etc. This reflects a focus on growth and efficiency over equity. Thus, although trade liberalization may be advantageous, the crucial factor in how advantageous and to who depends on how countries manage the process of integrating into the global economies. For example, employment creation through economic growth is often also accompanied by job destruction as labor moves from one sector or industry to another. In the absence of social safety nets, not only does such economic insecurity potentially push people into poverty, but it can also impact on health through the stress caused by economic and social dislocation.

Another important aspect of macroeconomic growth and health is that of the stability of the growth. Economic instability results in volatile markets, increased frequency of external shocks, and increased impact of such shocks. These translate into economic insecurity for an individual, which is closely linked to increased stress-related illness. It will also affect the adequacy of financial planning for ill-health by the household and the (public and private) health sector, and generate investor reluctance (including within the health sector itself).

Economic stability is affected, among other things, by the proportion of income/growth dependent on trade, with the general view that trade liberalization, especially in financial services and in the movement of capital, results in volatile markets. Of course, being an open economy does not automatically lead to economic instability/shocks – it is smaller, often developing countries, where trade contributes a much higher share of GDP that are more vulnerable as they rely more on imports and exports.

Macroeconomics And Risk Factors For Disease

It is well documented that there are many ‘social determinants of health,’ which refer to the general conditions in which people live and work and which influence their ability to lead healthy lives. These include factors such as employment, nutrition, environmental conditions, and education. These ‘social determinants’ contribute to the risk of different diseases and are often seen to differ in their role in influencing communicable and noncommunicable diseases.

The contribution of macroeconomics to the spread of communicable diseases is made in two ways. First, the overall environment in which people live (concerned with pollution, sanitation, etc.) is determined – in large part – by their income and wealth. Second, the increased international movement of people, animals, and goods associated with increased trade will affect the movement of disease. This is illustrated well by the example of SARS and other areas.

Perhaps less obvious is the relationship between macroeconomic activity and noncommunicable disease. Although macroeconomic growth can be beneficial when it leads to an expansion in the consumption of the goods that improve health, such as clean water, safe food, and education; it also facilitates the increased consumption of goods which may be harmful or hazardous to health, which may be termed ‘bads.’ Trade liberalization will reduce the price of imported ‘bads’ through reduced tariff and nontariff barriers, and increase the marketing of ‘bads,’ such as tobacco, alcohol, and ‘fast food.’ In the case of alcohol and tobacco, the development of regional trade agreements have helped to significantly reduce barriers to trade in tobacco and alcohol products, by breaking up the hitherto protected markets, contributing to enhanced consumption.

In terms of food-related products, increased macroeconomic integration will affect the entire food supply chain (levels of food imports and exports, foreign direct investment in the agro-food industry, and the harmonization of regulations that affect food), which subsequently affects what is available at what price, with what level of safety, and how it is marketed. For example, in what is termed the ‘nutrition transition,’ populations in developing countries are shifting away from diets high in cereals and complex carbohydrates, to high-calorie, nutrient-poor diets high in fats, sweeteners, and processed foods. Increased trade liberalization is one driver of the nutrition transition because it has had the effects of increasing the availability and lowering the prices of foods associated with the growth of diet-related chronic diseases, as well as increasing the amount of advertising of high calorie foods worldwide. Furthermore, trade and economic development encourages the use of labor-replacing technologies, such as cars, and creates greater leisure time, both of which in turn can be seen to encourage more sedentary lifestyles.

Macroeconomics And The Health Sector

Perhaps the most visible link between macroeconomics and health is at the overall level of health care spending. Most nations, rich or poor, face the problem of rising health care costs and confront two basic questions: How to finance this rising burden and how to contain the pressures for health expenditure growth. Here, the critical issues relate to government-funded health care, where the ability to finance and/or provide public services is determined by tax receipts. Tax income is broadly dichotomized into taxes that are ‘easy to collect’ (such as import tariffs) to those that are ‘hard to collect’ (such as consumption taxes, income tax, and value added tax). Tariff revenues are a very important source of public revenues in many developing countries.

Trade liberalization, by its nature reduces the proportion of government income from ‘easy to collect’ sources. Although theoretically, governments should be able to shift tax bases from tariffs to domestic taxes, such as sales or income taxes, in practice, developing countries, especially low-income countries, find this difficult, especially because of the informal nature of their economies with large subsistence sectors. Low-income countries are usually able to recover only approximately 30% of the lost tariff revenues resulting in a decline of government income available to pursue public policies, be it through health care, education, water, sanitation, or a social safety net.

The exchange rate is also a key determinant of the relative prices of imported and domestically produced goods and services. For many countries, products such as pharmaceuticals, but also various elements of other technologies, such as computer equipment, surgical tools, and even lightbulbs, used to provide health care are imported. Changes in the exchange rate brought about by macroeconomic developments may therefore see the price, and hence cost, of health care increase or decrease. Conversely, changes in demand for domestically produced goods from overseas importers may see the price of those goods domestically change in response (e.g., increased foreign demand may push up local prices). Increased linkage between economies at the macrolevel thus generates greater levels of exogenous (i.e., beyond the domestic health sector control) influences over prices, and hence cost of health care.

Finally, the health sector is increasingly involved in the direct trade of health-related goods and services. For instance, spending on pharmaceuticals represents a significant portion of health expenditure in all countries. Pharmaceuticals are also the single most important health-related product traded, comprising approximately 55% of all health-related trade by value (the share of the next most significant health-related goods traded, small devices and equipment, is o20%). The market is highly concentrated, with North America, Europe, and Japan accounting for approximately 75% of sales (by value). Overall, high-income countries produce and export high-value patented pharmaceuticals and low and middleincome countries import these products; although some produce and export low-value generic products. This leads to many developing countries experiencing a trade deficit in modern medicines, which often fuels an overall health sector deficit.

Trade in health capital and services has also expanded greatly in the last decade, in large part due to improvements in information and communication technology. These improvements have contributed, for instance, to the remote provision of health services from one country to another, known as ‘e-health.’ Examples of services provided include diagnostics, radiology, laboratory testing, remote surgery, and teleconsultation.

Another type of trade in health services arises from the consumption of health services abroad. This is also known as ‘health tourism’ and it entails people choosing to go to another country to obtain health care treatment. This attracts approximately four million patients each year, with the global market being estimated to be US$ 40–60 billion.

As liberalization increases and migration becomes easier, the movement of people across borders also increases. As a result, many health professionals choose to leave their home countries for richer, more developed ones. This is the case for doctors, nurses, pharmacists, physician assistants, dentists, and clinical laboratory technicians. It is estimated that in the UK, the total number of foreign doctors increased from 20 923 in 1970 to 69 813 in 2003. These figures may not seem that significant, but they often represent a large share of a country’s total doctors. In Ghana, for example, the number of doctors leaving accounts for 30% of the total number of doctors.

Conclusion

Health is essential not only for human development, but also for economic development. Economic development also significantly influences health. This reciprocity means that activities at the macrolevel are increasingly important to population health, and the provision of health care.

The growing interconnectedness between countries especially through greater trade and trade liberalization means that health sectors are more vulnerable to shocks from events that are happening around the world. It is therefore of critical importance that those concerned with health and health care have an understanding of the core issues.

Bibliography:

- Bloom, D. and Canning, D. (2000). The health and wealth of nations. Science 287(5456), 1207–1209.

- Blouin, C., Chopra, M. and van der Hoeven, R. (2009). Trade and social determinants of health. The Lancet 373(9662), 502–507.

- Blouin, C., Drager, N. and Smith, R. D. (eds.) (2006). International trade in health services and the GATS: Current issues and debates. World Bank.

- Hsiao W. and Heller, P. S. (2007). What Should Macroeconomists Know about Health Care Policy? IMF Working Paper WP/07/13.

- Pritchett, L. and Summers, L. H. (1996). Wealthier is healthier. The Journal of Human Resources XXXI, 841–868.

- Sachs, J. (2001). Macroeconomics and health: Investing in health for economic development. Report of the Commission on Macroeconomics and Health, Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Smith, J. (1999). Healthy bodies and thick wallets: The dual relationship between health and economic status. Journal of Economic Perspective 13(2), 143–166.

- Smith, R. D. (2012). Why a macro-economic perspective is critical to the prevention of non-communicable disease. Science 337, 1501–1503.

- Smith, R. D., Chanda, R. and Tangcharoensathien, V. (2009). Trade in health-related services. The Lancet 373, 593–601.

- Smith, R. D. and Correa, C. (2009). Trade, trips, and pharmaceuticals. The Lancet 373, 684–691.

- Smith, R. D. and Lee, K. (2009). Trade and health: An agenda for action. The Lancet 373, 768–773.

- http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2008/apr/29/philippines The Guardian.

- http://www.sundaytimes.lk/070527/FinancialTimes/ft306.html The Sunday Times.