A fair society should give individuals equal opportunities to realize their own life project. Health is of utmost importance for the flourishing of individuals. It seems, therefore, self-evident that inequality in health should get an important place on the fairness agenda. Yet, this seemingly obvious statement raises difficult issues. First, is all inequality in health necessarily unfair? Some health inequalities can be seen as ‘unavoidable,’ because they are due to biological factors or simply reflect bad luck. Should we not rather target those inequalities that are caused by the organization of our society, and in particular the health inequalities that are linked to indicators of socioeconomic status such as income, wealth, education, and social class? Socioeconomic inequalities have indeed been the main focus of the research, both in the public health and in the economic literature, and they also figure most prominently in policy statements. Yet, this raises a second, similar, question: Are all socioeconomic inequalities necessarily unfair? What if they are partly caused by individual behavior, such as smoking and drinking, or by choices about where to live and what kind of work to pursue? Should people not be held responsible for their lifestyle choices? And if so, should our measure of unfairness not in one way or another take into account this element of individual responsibility? Third, no matter how important health is for human flourishing, it is not the only important dimension of well-being. Does it make sense to focus on health only? Should we not integrate health inequality in an overall view of unfair inequality in well-being?

These questions are the main focus of this article and therefore other important issues are left aside. First, an explicit defense of egalitarianism will not be constructed and it will simply be taken for granted that some form of equality is necessary for fairness. The real question is: Equality of what? Second, the possible trade-off between total health and its distribution will not be considered. If spreading information about healthy lifestyles leads to an increase in average life expectancy but at the same time to growing inequality (e.g., because different cognitive capacities lead to differences in the efficiency of processing this information), a complete evaluation of the policy requires trading off these two effects. The focus here is on the specification of the fairness element in this trade-off. Third, unfairness is not exclusively a matter of health outcomes but has also a procedural element: Many will not accept that unfair health inequalities should be tackled by introducing explicit discriminatory practices into the process of accessing health care. Fourth, health can be measured in many different ways. Mortality is one possible indicator, the number of chronic conditions another; and much work is based on subjective self-assessed health, either on a continuous scale or in discrete categories. Different health concepts may yield different fairness results. Moreover, the level at which these variables are measured will determine the kind of inequality measures that can be used. These measurement issues will be left aside and the focus will be on the conceptual question: What is unfair health inequality?

Pure Health Inequality

The most straightforward approach is of course to consider simply all health inequalities as ‘unfair.’ Provided that health can be measured on a ratio scale, the degree of unfair health inequality can then be gauged by any of the measures that have been developed in the literature on income inequality (such as the Gini or Atkinson coefficients), and one can also draw the traditional Lorenz curve with the cumulative share of the population on the horizontal axis and health on the vertical axis. The closer this curve is to the diagonal, the smaller is inequality in health. The only difficult issue in this context is the choice of an adequate measure of health. All the rest is standard.

However, the question is, whether such pure health inequality an interesting concept? Suppose the inter-regional differences are to be checked in the performance of a health care system. It is observed that mortality is higher in region A than it is in region B. Yet, it is also observed that the population is on average older in A than it is in B. In that case it could be highly misleading to derive conclusions about the relative performance of the health care system in different regions from the simple differences in mortality. A correction for age seems necessary. In this spirit, the epidemiological literature has derived different methods of standardization of the raw measures by making use of the information from a reference group (e.g., the overall population in the country). Direct standardization estimates the mortality rate that would be obtained in regions A and B in the hypothetical situation in which they had the same age structure as the reference group. Indirect standardization first calculates the hypothetical mortality rate that would have been observed in regions A and B if the mortality rates for the reference population were applied to the age structure of the respective regions. One then computes standardized mortality rates by taking the ratio of the observed mortality rates with these hypothetical rates.

Although the use of standardization seems justified in this application, it has also been advocated for measuring unfairness in health. The authoritative World Health Organization Commission on Social Determinants of Health has emphasized that health inequity only arises where systematic differences in health are judged to be avoidable by reasonable action. Naively applied, this view implies that age and gender differences in health should not be seen as unfair because they can be largely explained by biological factors that are ‘unavoidable.’ One may deplore these differences, but nature itself cannot be fair or unfair. Although this is a popular opinion, it is controversial. It is hard to deny that social and technological developments interact with this biological background. This is especially obvious for gender: Health inequalities between men and women are definitely not only caused by biological factors but also by the position of men and women in society, including the way they are treated by the health care system and in the labor market. The rapid increase in male but not female mortality in the 1990s in Russia and other former Soviet Union countries, during the transition from a planned to a market economy, is a striking illustration of how socioeconomic factors can impact on gender inequalities in health. The same point can also be made with respect to age: Everybody dies, but health and mortality among the elderly depend on the way society is organized. Even the effects of different genetic endowments cannot really be seen as ‘unavoidable:’ Not only will the rapid technological developments in the domain of total genome analysis increase the potential of interventions in the near future (e.g., for eradicating diseases caused by genetic defects) but also it has become clear that phenotypical differences are almost always the product of interactions between the genetic endowment and the socioeconomic and natural environment. The latter can be influenced by policy. Biological differences do exist, but they do not completely determine the resulting health situations. The practice of quasi-automatic standardization for age (and even worse, for gender) may, therefore, hide important aspects of unfairness that follow from the differences in the treatment of women and the elderly in different countries or in different time periods.

Socioeconomic Health Inequalities

Whatever the position taken with respect to the effects of biological factors, most people would agree that health inequalities related to socioeconomic status in terms of income, wealth, education, or social class are particularly unfair. Differences in socioeconomic status are on their own already an indicator of injustice – and things get worse if individuals with a better socioeconomic status also are in better health. Both the public health and the economic literature have by now produced overwhelming evidence for the existence of such socioeconomic inequalities in health, with different health measures, for different countries and in different time periods.

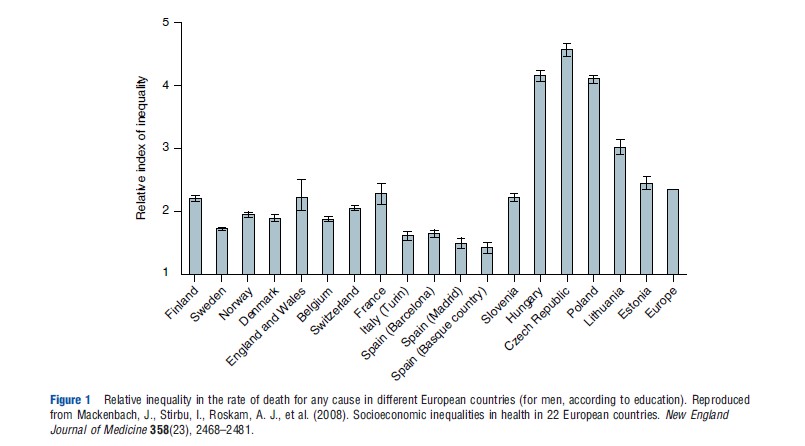

Regression-based measures based on gaps or ratios between two extreme groups have been especially popular in the public health literature. These have the advantage of being very simple to interpret. As an example, Figure 1 shows the ratio of the estimated death rate from any cause for males at the lowest level of education over the estimated death rate from any cause for males at the highest level of education. All measures are standardized for age. The results are striking. In countries like Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Poland, mortality differs between the lower and upper ends of the education scale by a factor of more than 4. Similar results are found with other measures of socioeconomic status (such as income and occupation) and indicators of health (such as self-assessed health).

Economists have studied the same phenomenon using the concentration index. The concentration index is a measure of the area between the concentration curve and the diagonal, where the concentration curve is drawn with the cumulative share of socioeconomic status (e.g., income) on the horizontal axis and the cumulative share of health on the vertical axis. Compared with the extreme group measures often used in the public health literature, the concentration index has the advantage of taking into consideration the whole distribution. Here also, standardization for age (and sex) is quite common.

Although their methods differ, the economic and public health literature concur with each other in finding strong socioeconomic inequalities in health. This is definitely a finding with much relevance for evaluating the fairness of the social arrangements. Yet, from a broader perspective, two questions can be raised. Are all socioeconomic inequalities necessarily unfair? And how do socioeconomic inequalities fit in a broader view on fair health inequality?

Are All Socioeconomic Inequalities ‘Unfair?’

After having observed and measured socioeconomic inequalities in health, a logical next step is its explanation. Different factors have been documented in the literature. Health and mortality inequalities may be caused by differences in working and housing conditions or by differences in access to good quality health care (apparently, an important factor explaining the poor results for the Eastern European countries in Figure 1). Most people will agree that these are indications of unfairness. However, socioeconomic differences in lifestyles are another important cause of the health differences, for example, smoking has a huge effect on health. This empirical finding has led to a sometimes heated debate about the fairness of the resulting inequalities. Should people be held responsible for differences in lifestyles? A positive answer to this question would mean that at least a fraction of the observed socioeconomic inequalities is not unfair.

The debate on the causes of socioeconomic inequalities in health has recently been considerably enriched and deepened by the rapidly growing empirical literature on the effects of childhood circumstances. Childhood circumstances do not only have a direct effect on adult health but also influence adult socioeconomic status and adult lifestyles. Different channels of influence have been documented. First, there is a direct effect of the prenatal (fetal) environment on adult health and lifestyle. As an example, it has been shown that the cohort of children born from mothers who were pregnant during the influenza pandemic of 1918 had a larger chance of being physically disabled in 1970. Second, illness and socioeconomic status in childhood may have lasting effects on adult health and lifestyle. This may be true even if adult income has hardly any effect on adult health. Third, childhood circumstances may affect the socioeconomic status (including the level of human capital) of young adults and this then may influence adult health and lifestyle. The three channels can work together, but opinions differ about their relative importance. Such different beliefs may lead to different ideas about the (degree of) unfairness of the observed socioeconomic health inequalities if the latter are caused by differences in lifestyles. This issue will be discussed in the next Section Unfairness and the Causes of Inequality: A General Framework.

Other ‘Unfair’ Inequalities

The literature on socioeconomic inequalities in health can also be seen as too narrow from another perspective. Even when disregarding age–gender differences (a position that, as argued, is not beyond criticism), socioeconomic inequalities are not the only cause of unfair health inequalities. Another (obvious) example is provided by regional inequalities. Regional inequalities in health may be linked to differences in economic infrastructure and amenities and the quality of the overall living environment. They may also be caused by differences in the relative performance of the health care system – a natural indicator of unfairness in an National Health Service context where a central government decides about the regional distribution of the available funds. In the US, the debate on health disparities has mainly focused on the effect of race, which can certainly be seen prima facie as a case of unfair health inequalities.

A priori, one might think that it is possible to distinguish explicitly these different examples of unfair inequalities and to analyze each of them separately. Although such a separated approach indeed may generate useful insights, it begs the question of how these different ‘unfair inequalities’ should be aggregated in order to obtain an overall measure of unfair health inequality in a given country at a given point in time. Moreover, there may be important interactions between the various ‘unfair’ inequalities. Focusing only on race in the US context means that one will tend to neglect the important fact that socioeconomic status mediates (at least partly) the relationship between race and health. However, focusing on socioeconomic status only may lead one to forget the fact that there may be (unfair) health differences between people from different races but with the same socioeconomic status. The choice of perspective may reflect a philosophically different view of the world and may have political consequences. Indeed, focusing either on race or on socioeconomic status alone will inspire different policy measures.

Unfairness And The Causes Of Inequality: A General Framework

The different questions and remarks raised in the previous sections converge on the same basic idea: there are many different factors leading to health inequalities. Some of these explanatory factors point to unfairness (e.g., socioeconomic status, race, and access to health care); others may reflect individual responsibility (e.g., lifestyles). Inequalities resulting from the former may be seen as ethically illegitimate, inequalities resulting from the latter may not offer a reason for concern. If this general and abstract picture of the world is accepted, a coherent framework is needed that makes it possible to integrate these different aspects.

Suppose, for simplicity, that the health situation of an individual is determined by two variables only: income and lifestyle. Suppose also that the position is taken that health differences due to income are unfair, whereas due to lifestyle are legitimate. Two caveats are in order here. The method is not limited to two variables (it can be applied to any number of explanatory factors) and the method does not presuppose that individuals are responsible for lifestyle (it can be applied for any partitioning of the set of explanatory variables in ‘legitimate’ and ‘illegitimate’ factors). This simplistic example is considered only to illustrate a more general method.

A first approach is to calculate for each individual the health status a person would reach with his/her own income but with a reference value for lifestyle. Because this reference lifestyle is kept the same for all individuals, the inequality in the resulting hypothetical values will only reflect income differences and is, therefore, a measure of unfair health inequality. Call this measure direct unfairness. A second approach calculates for each individual the health status a person would obtain with his/her own lifestyle but with a reference value for income. This can be interpreted as the health situation a person would reach in a ‘fair’ situation, because the (unfair) effect of income differences is removed. The difference (or the ratio) between an individual’s actual health status and this hypothetical fair health status can be seen as an individual fairness gap – and the inequality in these fairness gaps is a measure of overall unfair health inequality. Note the very close analogy between direct unfairness and the fairness gap on the one hand and direct and indirect standardization on the other hand.

In general, the two measures (direct unfairness and the fairness gap) do not coincide. How then to choose between them? It seems natural to impose that an adequate measure of unfair inequality should only be zero if there are no illegitimate inequalities left, i.e., if two individuals with the same lifestyle reach the same health outcome. It can be shown that the fairness gap satisfies this so-called compensation requirement, whereas direct unfairness does not. In this sense, the former is to be preferred. There is a price to be paid, however: the compensation requirement implies that if lifestyle affects health differently in different socioeconomic groups, the resulting health differences are interpreted as unfair. If one prefers a stricter position on responsibility and considers all lifestyle effects as fair, one should rather focus on the measure of direct unfairness.

As emphasized before, the methods sketched are general and can be applied to any partitioning of the set of explanatory variables into ‘legitimate’ and ‘illegitimate’ causes of health inequalities. Age–gender standardization boils down to considering ‘age’ and ‘gender’ as legitimate sources of differences. Focusing on socioeconomic or racial or regional inequality means that one interprets socioeconomic status or race or region as an illegitimate source of inequality, and (implicitly) all other sources as legitimate. Combinations are also possible, of course. Even pure health inequality can be accommodated in this broader framework: it is the extreme case in which all the causes of inequality are seen as unfair. One of the advantages of the general method described here is that it allows for sensitivity analysis, i.e., measures of unfairness can be calculated and compared for different possible partitionings.

Ultimately, the choice between different interpretations of unfairness should be made on philosophical or ethical grounds. Broadly speaking, it is possible to distinguish two approaches in the philosophical and welfare economic literature on the topic. The first defines responsibility as control. In this view, individuals should be held responsible only for those variables that they in one way or other choose themselves. At first sight, this seems a natural approach and it has also become the most popular. Yet, it raises the difficult question of what is really under the control of individuals in a social science perspective with a deterministic view of the world. If the findings on genetic and prenatal influences and on childhood circumstances are taken seriously, there does not seem to be much room left for genuine choice. A second approach holds people responsible for their preferences, i.e., for their own life project, even if this life project is not fully under their control and is (unavoidably) influenced by their education and social environment. This latter approach looks less like a kind of ‘disciplining’ device and can also be formulated in emancipatory terms as a way to respect the dignity of all individuals by giving them the freedom to choose their own lifestyle.

From a pragmatic point of view, one has to come down from these broad philosophical perspectives to classify the specific empirical variables. This is not a trivial exercise, and different observers will have different opinions. Is level of education a matter of choice? Does smoking behavior under the influence of social pressure and advertising reveal genuine preferences about a life project? One cannot give a convincing answer to these questions – and therefore one cannot construct an adequate measure of unfair health inequality – if one does not first have a good insight into the different channels through which these specific variables affect health outcomes. Indeed, there is no a priori reason to treat the various channels similarly in terms of fairness. Consider socioeconomic status. Its influence on health may reflect a direct effect of genetic endowment, the prenatal environment, and/or childhood circumstances; it may capture differences in lifestyles because of different capacities of information processing as a result of differences in human capital that for their part may follow from differences in childhood circumstances or from educational choices much later in life; it may reflect differences in health behavior that reflect different ideas about what is important in life; it may follow from differences in working conditions, themselves partly chosen but from a restricted opportunity set. To measure adequately unfair health inequality, a good explanatory framework is first needed that distinguishes between these different channels as well as possible.

A good explanatory framework is not only necessary to measure unfair inequality but also it is essential from a policy point of view: Health and health inequalities are not only influenced by health care arrangements. Quite the contrary, certainly if the interest is in the health of the most vulnerable social groups, labor market status, working conditions, housing, and education are at least as important. This raises immediately the deeper question about how to fit unfair health inequality into the broader picture of overall unfairness.

Health And Well-Being

Consider a policy that lowers income support for the most vulnerable groups in society but makes a huge investment in their access to health care. The result is a marginal decrease in unfair health inequality, but a considerable increase in income inequality. Should it be considered as a move toward a fairer society? Or what about a policy that improves the labor market opportunities for the unskilled, leading to a sharp improvement of their material well-being but at the same time to a slight increase in health inequality because of the increase in stress? In both cases, information about unfair health inequality is insufficient to evaluate the overall unfairness of these policies: Well-being has more than one dimension, and all relevant dimensions have to be taken into account if a global judgment is to be formulated.

This conclusion seems so obvious that one may wonder why the bulk of research and policy attention goes to the partial issue of socioeconomic health inequality. The answer to this puzzle seems to lie in the kind of results that are described in the Section Socioeconomic Health Inequalities: because overwhelming evidence for socioeconomic inequalities in health is found to be at the expense of the poorer groups in society, there is a cumulative effect and the tradeoffs sketched in the previous paragraph may seem to be of second-order importance. Yet, this kind of contingent reasoning is not sufficient to defend a normative position in principle. As a matter of fact, tricky issues arise when one considers only these partial inequality measures. The concentration index will always decrease (suggesting a less unfair situation) if health is transferred from someone who is better off in terms of socioeconomic status to someone who is worse off, independently of their own initial health situation. Moreover, it can be shown that more egalitarian countries will do worse on the most popular measures of socioeconomic health inequalities (including the extreme group measures and the concentration index), if there is a causal link from health to income. This is a mechanical effect of the way in which these measures are constructed and it explains partly why, for example, the Scandinavian countries do not do very well in Figure 1 (and in similar empirical exercises). All this strengthens the conclusion that it is necessary to go beyond such conditional inequality measures and move to overall inequality in well-being – taking into account, of course, that health is an essential element of well-being.

Multidimensional approaches to well-being have grown in popularity recently, as reflected in the success of Sen’s capability approach. Techniques for multidimensional inequality measurement have now been firmly established. However, neither of these two approaches offers an attractive solution to the aggregation problem, i.e., the problem of weighting the importance of the various dimensions so as to obtain one overall measure of individual well-being. The capability approach leaves this question largely open, whereas multidimensional inequality measures implicitly ‘solve’ the problem by imposing a functional form in a rather ad hoc way. Yet, in a democratic society, it seems natural to require that the weighting of the different dimensions should reflect the preferences of the individuals themselves. Well-being does not necessarily coincide with subjective happiness either: it would be strange to claim that a healthy millionaire who feels depressed because he is not successful in having his poems published is worse off than a sick and poor woman who is reasonably satisfied with her life because she has learnt to adapt to her fate by lowering her aspirations. The real challenge consists in formulating a concept of individual well-being that does respect preferences, although at the same time correcting for aspirations. Recent developments have shown that the traditional welfare economics concepts of money-metric utility and equivalent income offer interesting perspectives in this respect.

References:

- Almond, D. (2006). Is the 1918 influenza pandemic over? Long-term effects of in utero influenza exposure in the post-1940 US population. Journal of Political Economy 114(4), 672–712.

- Bleichrodt, H. and van Doorslaer, E. (2006). A welfare economics foundation for health inequality measurement. Journal of Health Economics 25, 945–957.

- Brekke, K. and Kverndokk, S. (2012). Inadequate bivariate measures of health inequality: The impact of income distribution. Scandinavian Journal of Economics 114(2), 323–333.

- Case, A., Fertig, A. and Paxson, C. (2005). The lasting impact of childhood health and circumstance. Journal of Health Economics 24, 365–389.

- Currie, J. (2009). Healthy, wealthy and wise: socioeconomic status, poor health in childhood, and human capital development. Journal of Economic Literature 47(1), 87–122.

- van Doorslaer, E. and Van Ourti, T. (2011). Measuring inequality and inequity in health and health care. In Glied, S. and Smith, P. (eds.) Oxford handbook on health economics, pp. 837–869. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fleurbaey, M., Luchini, S., Muller, C. and Schokkaert, E. (2012). Equivalent income and fair evaluation of health care. Health Economics. doi:10.1002/hec.2859.

- Fleurbaey, M. and Schokkaert, E. (2009). Unfair inequalities in health and health care. Journal of Health Economics 28(1), 73–90.

- Fleurbaey, M. and Schokkaert, E. (2011). Inequity in health and health care. In Barros, P., McGuire, T. and Pauly, M. (eds.) Handbook of health economics, vol. 2, pp. 1003–1092. New York: Elsevier.

- Hausman, D. (2007). What’s wrong with health inequalities? Journal of Political Philosophy 15(1), 46–66.

- Kawachi, I., Daniels, N. and Robinson, D. (2005). Health disparities by race and class: Why both matter. Health Affairs 24(2), 343–352.

- Mackenbach, J., Stirbu, I., Roskam, A. J., et al. (2008). Socioeconomic inequalities in health in 22 European countries. New England Journal of Medicine 358(23), 2468–2481.

- Sen, A. (2002). Why health equity? Health Economics 11, 659–666.

- WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health (2008). Closing the gap in a generation. Geneva: WHO Press.

- Williams, A. and Cookson, R. (2000). Equity in health. In Culyer, A. and Newhouse, J. (eds.) Handbook of health economics, vol. 1B, pp. 1863–1910. Amsterdam: Elsevier (North Holland).