The origins of public health can be found in ancient Greek and Roman civilizations. Many of the prominent themes in the writings of that era, such as Airs, Waters, and Places from the Hippocratic corpus, have echoes in today’s major concerns about how one can have health amid both climate change and an increasing burden of noncommunicable diseases. The Greeks also developed the concept of city physicians. Their role, paid for by the city, was to look after the health of the citizens and to advise on the overall health of the city.

It is a constant difficulty for those working in public health as to how their specialty should be described. Every public health professional will be asked repeatedly during his or her career to explain exactly the meaning of public health. One useful conceptualization describes it as five different, but commonly encountered, images:

- The system and social enterprise.

- The profession.

- The methods (knowledge and techniques).

- Governmental services (especially medical, and for the poor).

- The health of the public.

Over the years, many definitions of public health have been used. These often seem to morphose at times of organizational crisis or reorganization. At these times, a definition is needed that fits with the prevailing or future circumstances. But in modern times, whatever definition is used for public health, there remains a publicly accountable system, which is staffed by professionals who identify with the task of improving the health of human populations. The question is, however, sometimes asked as to whether public health is really a system or a profession. In times past, it was sometimes, perhaps accurately, referred to as an ‘endeavor.’

The Origins Of The Public Health Profession

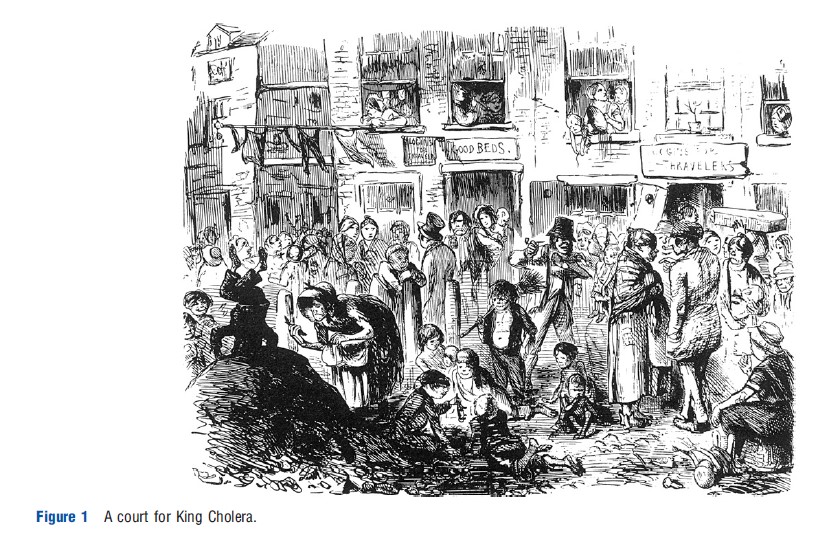

The history of public health tells us that the major improvements in the health of populations have resulted not through the efforts of medical systems orientated toward the care of individuals with specific diseases but through the improvement of general social conditions such as housing, food supply and quality, water, and sanitation (see Figure 1). Although this is a historical perspective, being mainly associated with the nineteenth century sanitary revolution that started in England in the 1830s and 1840s, the rise in the importance of noncommunicable diseases globally, including obesity, diabetes, and alcohol-/tobacco-related diseases, has underlined the importance of primary prevention. The modern construction, the equivalent of the sanitary movement, is centered around the social determinants of health.

In the UK, the history of professional engagement with public health in a structured way dates back to the midnineteenth century when the post of Medical Officer of Health (MOH) was created among the English local authorities. The first MOHs were mostly part-time, who combined the local authority post with clinical practice. The first formal qualification in public health was the Diploma in State Medicine that was instituted in 1871 by Trinity College in Dublin. The breath of public health concern was illustrated by the inclusion in the syllabus of subjects such as statistics, meteorology, and engineering. It was not until the early-twentieth century that the possession of a professional qualification in public health became compulsory in Britain for those holding the MOH post. Other related qualifications, such as those awarded to sanitary inspectors, developed separately but simultaneously with the medical world.

In the USA, the first public health structures came in to being in the second half of the nineteenth century in the port cities on the East coast. By the 1870s and 1880s, most States had established their own public health structures. It was industrialization and rapid population growth that spurred the development of public health in the big cities, just as it had happened in England.

It was the inception of the National Health Service (NHS) across the UK in 1948 that created different strands of medical engagement with population health issues. The main professional public health staffing, and a wide range of public health services, had remained within the remit of local authorities. The new structures of the NHS, however, required population health skills, particularly in healthcare planning, and medical officers were appointed at a senior level within these new organizations. The skill set however was different from that required in the traditional public health role, and the existing professional organizations were not well fitted to service the future requirements of this new mixture of professional roles.

The opportunity to reconstruct the profession engaged in population medicine, in whatever role, came with the 1974 (1973 in Northern Ireland) reorganization of the NHS. It finally brought together the three key components of hospital services, primary healthcare, and public health in the NHS. The transfer of public health from local government into the NHS was not without its problems. Many of the MOHs opposed the transfer and did not appreciate the move of focus away from issues such as infectious disease, housing conditions, educational medicine, and child health. Instead, they found themselves deeply engaged in issues of healthcare management, and were frequently relegated to a purely advisory role with limited command over staff and resources.

This major change in the nature of the profession was the greatest for more than a century, and it was necessary to reconstruct the organs of the profession to match the new challenges. In particular, in order to leave behind the historical baggage of sanitarianism that attached to the title ‘public health,’ it was felt that the branch of the medical profession dealing with population health required a new name of ‘community medicine’ – although this attempted change of name was short-lived as seen below forthwith. The transfer of public health functions from the local authority world into the NHS was not complete however, as environmental health responsibilities still remained with councils.

Academic Public Health

By the first half of the twentieth century, the development of the academic endeavor surrounding public health had moved substantially from its origins in the sanitary revolution. The decline of infectious diseases in Britain had resulted in a change in perspective amongst doctors who were interested in the academic questions surrounding disease prevention and control. From the 1930s onwards, a clinical perspective, which was more closely rooted in the practice of bedside medicine than in sanitarianism, had developed to become the predominant ethos of the academic public health world. The individual being most closely associated with this trend, for leading it in many ways, is John Ryle. Ryle was a political progressive who moved from his post as Professor of Physics in Cambridge University to lead the newly created Institute of Social Medicine at the University of Oxford. He believed that the new paradigm of social medicine, as it thus became, should be based on the study of disease causation in populations of patients. This became the predominant academic approach that was closely associated with the development of epidemiological methods in studying noncommunicable diseases. Although academic departments continue to teach courses leading to the Diploma in Public Health, their research has actually shifted substantially toward a social medicine focus.

The academic bedrock in the USA was established following the publication of the Welch-Rose Report in 1915. Substantial funding from the Rockefeller Foundation in 1916 has enabled the founding of what is now known as the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. The subsequent development of a network of schools of public health across the USA has set the basis for the system of public health training that continues even today.

The Creation Of Community Medicine

The transfer of public health responsibilities and staff to the NHS in 1974 was an opportunity to create a unified group within the medical profession of those whose activities were orientated toward improving the health of the population. Thus three strands were brought together; the former Medical Officers of Health and their staff, the medical administrators in the hospital service, and the social medicine and epidemiology academics. The new title chosen for this unified specialty was ‘community medicine.’ The creation of such a unified professional grouping had already been recommended by the 1968 report of the Royal Commission on Medical Education, although it took the restructuring of the NHS to give it the momentum for producing the necessary organizational changes.

The Faculty of Community Medicine became the professional organization that was created to be responsible for the training and professional development of the specialty. It was an unusual creation in that it was a faculty of not one but three medical Royal Colleges: the Royal College of Physicians of London, the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, and the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow. Membership of the new Faculty was restricted to those who held a medical qualification and, following the period of its formation, to those who passed its two-part examination. It was therefore cast in the traditional mold of a medical college where the training programs followed the well-established pattern for the training of hospital consultants.

Multidisciplinary Public Health

As the great majority of national public health associations across the world have a multidisciplinary membership, the World Federation of Public Health Associations will not admit into membership an association that draws its membership from only one professional background. The American Public Health Association, founded in 1872, has a long tradition of multidisciplinary public health working and, in its case, it has been seen to add to the general strength of the professional group. In the USA, public health training has always been multidisciplinary. By 1938, federally funded training had been provided to more than 4000 people in schools of public health, of whom only approximately 1000 were medically qualified.

In the UK, although the move toward multidisciplinary public health was difficult for many of the more traditionally minded members of the specialty, the way forward was eventually greatly helped by the example of the Royal College of Pathologists that had for some time admitted both medical and nonmedical members. It was the creation of the new specialty grouping of community medicine in the 1970s that created the tensions. The very fact that training for senior positions in the new system was so closely modeled on the medical training scheme, and that the newly formed Faculty of Community Medicine only opened its doors to registered medical practitioners, was regarded as little short of an insult by many of the distinguished academics from disciplines other than medicine, who had been making such a substantial contribution to the various academic departments of social and preventive medicine across the country. The attempt to persuade academic departments to adopt the uniform title of ‘Department of Community Medicine’ was a failure. Many departments continued to operate with their traditional titles, whereas very few adopted the new title.

As the service component of community medicine found its footing in the new NHS structures during the 1980s, the skill mix began to develop in the building of departments. The multidisciplinary trend was particularly prominent in the growth of health education units as well as their development into the new and more progressive approach of health promotion. Similarly, the requirements in the new organizations for advanced skills in the handling and analysis of large datasets, accompanied by the development of small and usable computers, led to the development of groups of staff with significant epidemiological and statistical skills. The gradual opening up of postgraduate courses in public health to students from disciplines other than medicine meant that there was the beginning of a professional development pathway for nonmedical graduates that would to some extent mirror that of the doctors.

The steady growth of multidisciplinary working in both academic and service settings had gradually increased the demands for a proper career structure for nonmedics working in public health as well as for access to established and recognized training routes. At one point, there was a danger that the specialty would split into two or more professional groupings. However, with a great deal of diplomatic activity, it had eventually become possible to bring together the different factions. In 1997, the Tripartite Group (the Faculty of Public Health Medicine, the Royal Institute of Public Health and Hygiene, and the Multidisciplinary Public Health Forum) signed the Tripartite Agreement taking forward the development of multidisciplinary public health. This formed the basis for admission into the Faculty, on an equal basis, of public health professionals from different professional backgrounds. It also paved the way for equal access to official training posts in the specialty.

Training In Public Health

Across the world there are various routes of entry into specialized public health work. The most common by far is through studying for a Masters level degree in public health at a University or School of Public Health. In many countries, such training may be supplemented by further study to obtain a Doctorate level qualification, which may be obtained through a taught route or by research. This route is usually open to graduates from a wide range of disciplines and to those from vocational backgrounds such as nursing.

The US in particular has a very substantial number of Masters in Public Health (MPH) courses, and approximately 15 000 students study for a MPH every year. The Council on Education for Public Health accredits courses in public health in the USA and has recently started to operate internationally with accreditation taking place in Canada, Mexico, and France. Canada in particular has seen what is described by some as an ‘explosion’ in MPH courses.

The growth of academic qualification in public health is rightly seen as a bedrock for good public health practice in society. In some countries, however, a longer training period, that usually includes a MPH component, is regarded as the norm for those wanting to become specialists in public health. This is a system that is often based on the British approach to training, which parallels the system for training of doctors in clinical specialties. The approaches adopted in Ireland, Australia, and New Zealand – all involve a significant period of work-based training attachment as well as, in some cases, qualifying examinations.

System Failure

Although community medicine had become embedded within the NHS systems in the UK during the 1970s and 1980s, this had meant a substantial move away from the origins of public health, which were based on the concept of environmental concerns and infectious disease. The connection with NHS management and the involvement in the functions of NHS administration had meant that public health practitioners had moved ever further away from their origins, and this was not without consequence. There were a series of serious failures of the public health system, resulting in a significant number of deaths. Notably, these included the major salmonella outbreak in 1984 at the Stanley Royd Hospital in Wakefield and the 1985 Legionnaires’ disease outbreak at Stafford General Hospital. The then Chief Medical Officer (CMO) of England, Sir Donald Acheson, chaired a review of the public health system and published a report in 1988 entitled ‘Public Health in England.’ The major thrust of the report was that the specialty had drifted too far from its roots, neglecting some of the major risks to the population’s health. Two important outcomes were that the title ‘public health’ should be restored to the specialty and that the senior post holder at a local level should be designated as Director of Public Health (DPH). He or she was also mandated to produce an annual report on the health of the respective population in much the same way as the predecessor, the MOH, had done.

Doctors specializing in the control of infectious disease became separated from the generalist public health professionals in due course, a move that was reinforced by the incorporation of doctors into a new national body known as the Health Protection Agency, which itself disappeared in 2013. This separation of communicable disease control from general public health is contentious, and is regarded as creating a fault line in the specialty.

The Chief Medical Officer

It is very common for national health systems to have an individual operating at national level with the key responsibility for the population health aspects of the country’s health. Inevitably, a range of titles are used to designate such a role, but internationally, the generic title of CMO is often used – in the European Union, for example – even though in some instances, the incumbent may not be medically qualified. A study of all the counties in the European Union has shown that CMOs operate in a wide range of roles. This might be within the central Government Department of health concerns or within a separate agency in charge of undertaking national public health responsibilities. The role of the CMO also ranges from being purely advisory to having substantial executive powers and numerous staff. Very few European countries do not have any identifiable CMO-type posts.

In England, the local post of MOH preceded the post of CMO. The first MOH known to be appointed for a full-time post in the UK was Dr. William Henry Duncan of Liverpool. He was appointed in 1847 as a result of a private Act of Parliament that preceded the 1848 Public Health Acts. He became a well-known figure in the city to the extent of sharing with his contemporary, the famous London physician Dr. John Snow, the accolade of having a public house named in his honor. But although MOHs became prominent local figures, it was indeed the creation of the public health post currently known as CMO at the heart of Government that had become the most enduring one.

The first holder of the post of CMO was Dr. John Simon. He had been an active and outspoken MOH for London, who became the CMO of the General Board of Health in 1855. Never one to shy away from controversy, Simon continued to be a passionate advocate for the health of the population. He demanded that the post of CMO should be of prominence in the structure and functioning of the General Board of Health, and subsequently in the Privy Council. Although he resigned eventually because of the downgrading of the post – particularly on the issue of allowing direct access to ministers, yet Simon had firmly established the principle of a chief public health advisor to the government and the post continues to this day. Although it is nowhere specified that the CMO has to come from a public health background, this has in effect been the position until relatively recently. Only two of the CMOs in England have come from outside the public health system. The requirement to publish an annual report on the health of the population has been a key task of the CMO, which has been seen as analogous to the duty that fell to the MOH, and subsequently, to the DPH, at a local level. The CMO post is, however, under threat in the English system, as the current and 16th incumbent is not only from a nonpublic health background but is also on a short-term contract, and the post itself has been merged with the most senior research and development post in the Department of Health.

The USA has a similarly long-lived tradition of having a doctor close to the center of government. The first Surgeon General of the USA was appointed in 1871 and, unlike the UK position, is a political appointee. The incumbent holds office at the pleasure of the President, and although there is a tradition and public expectation that the Surgeon General will speak out on controversial issues, this at times has led to the President’s intervention to dismiss him or her. This has been seen most recently in the dismissal of a Surgeon General by President Clinton because of her statements on sexual health. Former Surgeon Generals have complained publicly regarding political interference in their erstwhile official roles (Figure 2). As in the UK, there is a presumption that the post of Surgeon General will be appointed from within the existing public health medical workforce.

A very significant difference between the public health workforce in the USA and the UK is with regard to their official status. In the USA, the Public Health Service Commissioned Corps is one of the uniformed services of government and its uniformed staff is therefore subject to a degree of military style discipline, with the Surgeon General holding the rank of Vice-Admiral in the service.

Future Directions

The development of international cooperation between organizations representing public health professionals appears to be on a steady upward trajectory. The African Federation of Public Health Associations was launched in April 2012, since then representing the latest step in the creation of an effective global, regional, and national network of public health bodies. The basic priority internationally is the development of a global approach to the public health workforce, which would recognize that strengthening the training and the role of public health professionals are key elements for improving global health.

In England, the most recent changes to the NHS have moved public health in a very different direction from the situation in other parts of the UK. The return of a substantial proportion of public health functions to local authorities is a major reversal of the 1974 reorganization. Similarly, the creation of Public Health England, an executive agency of the Department of Health, is remarkably a substantial centralization of power and authority. This centralization is to a greater extent than anything seen hitherto in public health in the UK. Meanwhile, public health in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland continues to be closely associated with the NHS. The effect on professional practice of the changes in England is not yet discernible. The Coalition Government in England has agreed to implement statutory regulation of the specialist cadre of the profession, and this may provide some protection in respect of the laisser faire approach that is likely to accompany the local control, which will rest with individual local authorities.

There is a real opportunity arising from the move to local government in England. Many of what are now known as the social determinants of health lie within the remit of local authorities. The ability to influence planning, housing, leisure and recreation, education, economic development, etc. is a prize worth griping. The ability to function effectively within what is a radically different environment is however likely to require a different set of skills from those most recently deployed in the NHS. In particular, the ability to deal efficiently and effectively with, and win the respect of, elected politicians will be at a premium.

The move of a substantial proportion of the public health workforce in England into local authorities will give a new opportunity to rethink approaches to ensuring the quality of public health practice. The current model that is based largely on processes such as audit and revalidation, which are drawn from the clinical world, may well prove to be inadequate in a world where professional hierarchy is dissolved. Instead, new approaches that aim to provide assurance regarding the quality of local public health departments may evolve. This may well be based on recent experience from the USA, where they have been trying to cope with a devolved system that displays significant variation in the quality of public health practice. The development of USA style accreditation systems for local public health departments is one way in which professional standards and development can be assured at a time of increased devolution of authority.

One of the important changes in recent decades has been the way in which doctors in clinical practice have moved away from engagement with preventative medicine and the major public health issues of the day. This is in stark contrast to the successes of the broader medical profession during the later half of the twentieth century in relation to issues such as tobacco, seat belts, crash helmets, and car windscreens. There have however been stark warnings that health services in developed countries will become unaffordable unless there is a wholehearted and wholesale engagement with primary prevention. If this is to materialize, stronger links will need to be forged between clinical medicine in health services and the operation of local authorities and others with control over the determinants of health. This has the potential to usher in a new era of preventative medicine in which the barriers between clinical medicine and public health that have been painstakingly erected over the past hundred years can start to be demolished.

References:

- Acheson, R. M. (1980). Community medicine: Discipline or topic? Profession or endeavour? Journal of Public Health 2(1), 2–6.

- Detels, R., Beaglehole, R., Lansang, M. A. and Gulliford, M. (2009). Oxford textbook of public health, 5th ed. (Online Oxford medicine edition 2011, doi: 10.1093/med/9780199218707.001.0001). Oxford University Press.

- Donaldson, L. J. and Scally, G. (2009). Donaldsons’ essential public health. Oxford: Radcliffe.

- Fee, E. and Acheson, R. M. (1991). A history of education in public health. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Jakubowski, E., Martin-Moreno, J. M. and McKee, M. (2010). The governments’ doctors: The roles and responsibilities of chief medical officers in the European Union. Clinical Medicine 10(6), 560–562.

- Pencheon, D., Guest, C., Melzer, D. and Muir Gray, J. A. (2006). Oxford handbook of public health practice. Oxford University Press. (Oxford medicine online edition 2010, doi: 10.1093/med/9780198566557.001.0001).

- Porter, D. (1999). Health, civilization and the state. London: Routledge.

- Sheard, S. and Donaldson, L. (2005). The nation’s doctor: The role of the chief medical officer, 1855–1998. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press.

- Turnock, B. J. (2004). Public health: What it is and how it works, 3rd ed. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen Publishers.