This article addresses the distinctive challenges of planning, financing, implementing, and evaluating public health policies in low- and middle-income countries. By public health is meant the science and art of promoting and protecting health and well-being, preventing ill-health and prolonging life through the organized efforts of society.

A key feature of low and middle-income countries is a health discourse that diverges in some key ways from that in high-income countries. In particular, ‘public health’ in high-income countries is a recognized and accepted subject area that is generally formally planned and structured, always with agencies with specific public health roles and sometimes even with a government minister for public health. Elsewhere, and especially in low-income countries, it tends to be assessed and planned in ways that are more fragmented, and less coherent, for reasons explored in this article.

What Is Distinctive About Low- And Middle-Income Countries?

Burden Of Disease

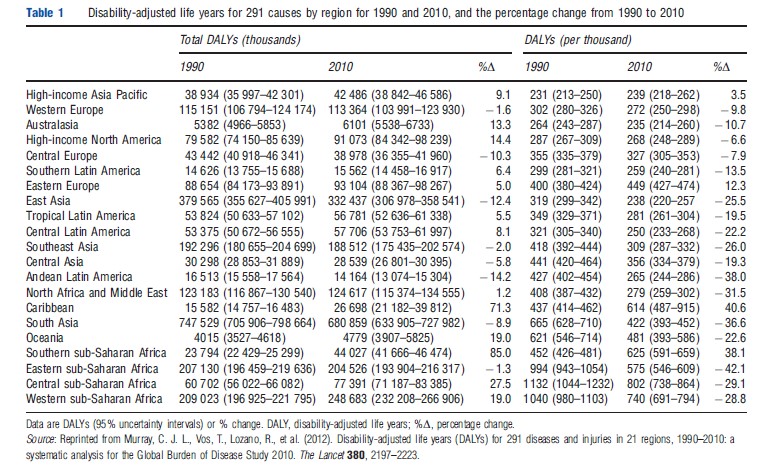

The global burden of disease (GBD) across the world has been studied for some time. In 2012, a comprehensive analysis was published for 2010, including comparison with the original 1990 analysis. It uses the metric of the Disability-Adjusted Life Year (DALY), which combines years of life lost due to premature death with years of healthy life lost due to illness and disability, for specific diseases and conditions. The regional breakdown is done by 21 geographical regions rather than broad country income grouping, although the identification of subregions does largely distinguish lower and higher income groupings within broader regions (e.g., Europe is disaggregated to Western, Central, and Eastern Europe).

Table 1 shows total DALYs and DALYs per thousand population by the 21 regions and the change between 1990 and 2010. A full discussion of the data is in the source article. Key points to note are that in 2010 as in 1990, poorer regions have a much greater burden of disease per 1000 population, with the regions with the greatest burden per 1000 being in sub-Saharan Africa. Note, though that these regions have seen some of the sharpest reductions in burden per 1000 (although a marked increase in total burden due largely to population growth).

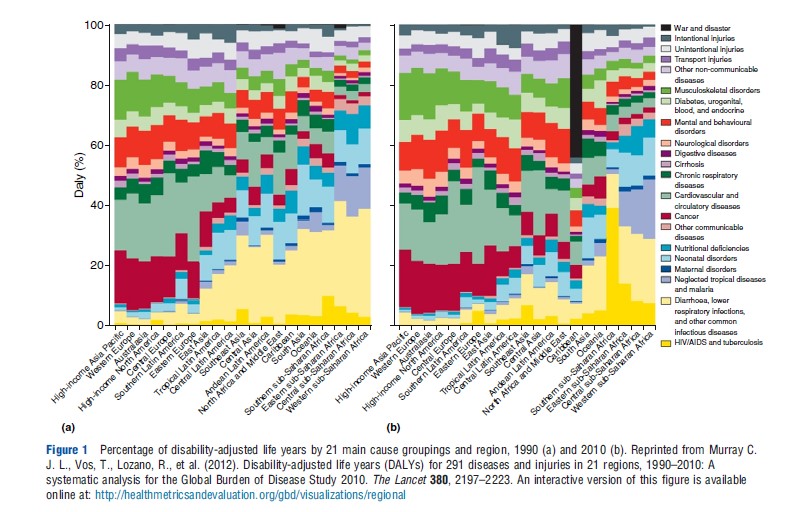

Figure 1 shows how the total burden of disease is broken down by broad cause in these 21 regions, comparing again 1990 and 2010. In 2010, high-income countries (high-income Asia-Pacific, Western Europe, Australasia, high-income North America, and central Europe) had only 7% of DALYs due to communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional disorders. Cancer and cardiovascular disease accounted for 36% of DALYs. In contrast, in east, west, and central sub-Saharan Africa, the former disease groups accounted for 67–71% of DALYS. Nonetheless, comparing 1990 and 2010, the great reduction in common infectious diseases in poorer regions is evident (the reduction in the light yellow bars), although the rise in HIV is very visible (in dark yellow) in southern and eastern sub-Saharan Africa. Even in the poorer regions there is a significant burden due to noncommunicable diseases and injuries; hence, the common label of the ‘double burden’ in low- and middle-income countries – the unfinished agenda of communicable diseases and the new burden of noncommunicable diseases and injuries. Analysis by age groups and region can be explored at the GBD website of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (https://www.healthdata.org/). For example, the analysis by region of DALYS in children under 5 shows vividly that disease in children is virtually absent in high-income regions and is concentrated in low-income regions.

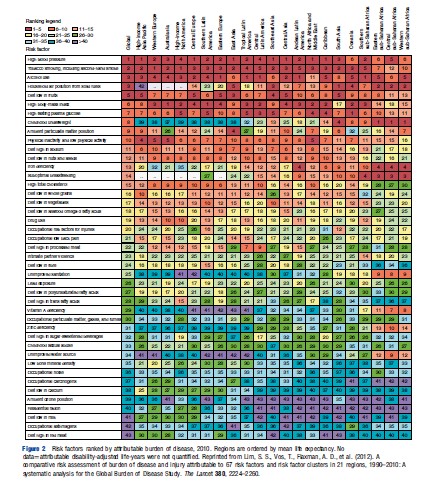

From a public health point of view, it is important to understand the risk factors that underlie the burden of disease. Figure 2 shows the relative importance for the 21 regions of the risk factors defined in the GBD study. For central, eastern, and western sub-Saharan Africa, for example, the three leading risk factors are underweight, household air pollution from solid fuels, and suboptimal breastfeeding. In South Asia, household air pollution ranks top, although the changing pattern of disease is shown by tobacco smoking and high blood pressure ranking 2 and 3. In high-income regions, top ranking factors are high blood pressure, smoking, alcohol use, and high body mass index. This demonstrates visibly how the pattern of risk factors changes as countries grow richer.

Economic Structure

Economic structures not only help explain the patterns of burden of disease but also have a strong influence on the capacity of countries to respond to public health needs.

Key risk factors have their origins in the economic structure of low-income countries. The overall low level of income, and high proportions of the population living in absolute poverty, help explain under nutrition and the unsafe living environments. ‘Structural’ factors, such as low levels of education and lack of access to employment and informal employment, also help explain the prevalence of unsafe sex which encourages the spread of sexually transmitted diseases (note that lack of data led to unsafe sex being omitted from the GBD risk factor list in Figure 2). In middle-income countries, growing affluence and changing behaviors associated with higher incomes, global spread of information and the influence of the multinational industry on diet and smoking help explain the very different pattern of risk factors.

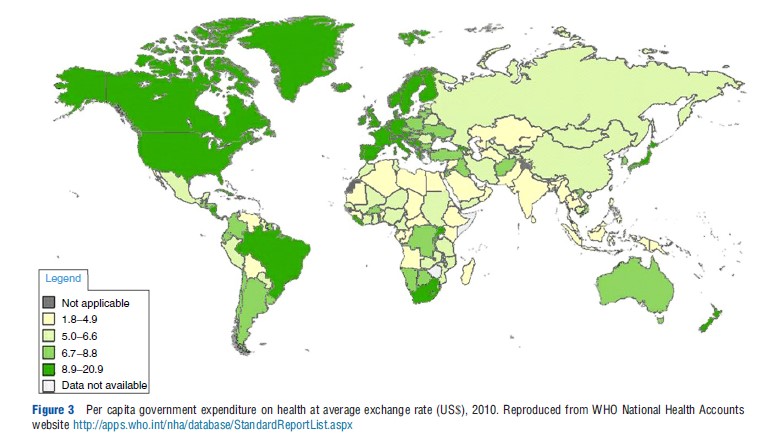

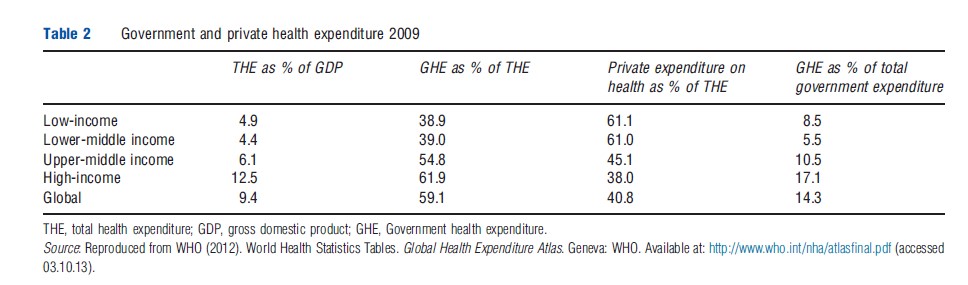

The poverty of a country severely affects its ability to finance an adequate response to public health needs. Figure 3 (taken from the WHO National Health Accounts website) maps levels of per capita government expenditure on health across the world in 2010, and Table 2 shows shares of total, government and private health expenditure by country income group in 2009.

Many low-income governments in Africa and Asia spend less than $34 per capita on all health care. Mean total health expenditure in 2009 in low-income countries was approximately 5% of GDP and less than half of this was channeled through government. In 2001, the WHO Commission on Macroeconomics and Health estimated that a set of 49 priority health interventions, largely for personal preventive and primary care, would cost 6% of the GNP of low-income countries. Hence, current levels of government expenditure are inadequate to fund these priority interventions and in addition are funding many other interventions, which might be seen as lower priority, notably high level hospital care, which is costly but benefits relatively few people. Although private out-of-pocket spending is often at least as high as government spending, the bulk of this is spent on over-the-counter drug purchases rather than the high-priority preventive activities needed to improve the health of the public.

Poverty has another consequence, that of low salaries for heath workers in the public sector. Professionals have always been internationally mobile, and improved communications have made it easier for professionals to move to high-income countries where salaries are higher. Moreover, in a context where government physicians often supplement their low government salaries by private clinical work, public health practice may be less attractive because it offers less scope to increase reputation through clinical practice in the public sector, and postings to the more rural and remote areas limit the opportunity for profitable private practice.

Low levels of government expenditure reflect another consequence of the economic structure, the difficulty of raising adequate taxation to finance public services. Low-income economies have a large share of their populations in the informal sector, making it difficult to levy direct taxes on a significant proportion of the total population.

Political And Social Institutions

A corollary of underdevelopment is that the political and social institutions needed to underpin an effective government tend to be weak. These include the institutions of democracy and representation, of civil society, and of professional groupings. One consequence for public health is that the ability to regulate health-damaging products may be far more limited than in the rich world. For example, low- and middle-income countries have come under pressure from the global tobacco industry, as well as self-interested governments who benefit indirectly from overseas tobacco sales through domestic tax revenues and employment, not to impose restrictions on the sale of tobacco or on cigarette advertising. In the late 1980s, the US used bilateral trade relations to exert pressure on countries such as Thailand and South Korea to open up their domestic markets to cigarette imports. Regulation of pharmaceuticals is also often very weak, leading to widespread and uncontrolled usage of antibiotics and antimalarials, for example, which can encourage the development of resistance. Artemisinin, a relatively new antimalarial, is a case in point. WHO has urged countries to adopt regulatory measures to stop the marketing of oral artemisinin-based monotherapies and to promote access to artemisinin-based combination therapies: the effect of the combination is to protect the individual drug elements from the development of parasite resistance. But artemisinin monotherapy remains widely available in many countries due to both inability to enforce regulation and the lack of separation of government and commercial interests.

Management Capacity In The Public Sector

Low- and middle-income countries often struggle to translate policies into action. For example, their plans usually do give priority to diseases and conditions that give rise to the greatest burden of disease, yet in practice coverage rates of interventions such as immunization, vitamin A, and emergency obstetric care, remain well below universal. Although to some extent this reflects a lack of prioritization in resource allocation decisions, it also reflects the limitations of management capacity. This encompasses not only trained managers but also management and information systems more broadly and ability to implement programs effectively across countries with poor communications infrastructure and often remote and hard to reach populations.

Influence Of Agencies External To The Country

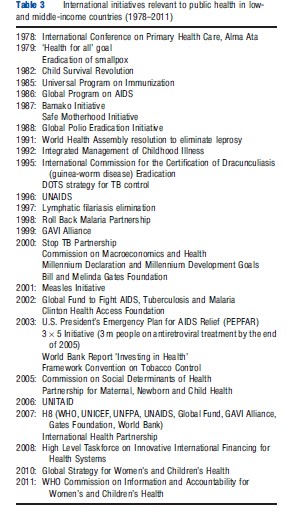

On average, external financing makes up 27% of the total health expenditure of low-income countries (but far less in middle-income countries). In the last decade or so, official development assistance for health has increased substantially in real terms: it amounted to $7331 m in 2003, and $17 856 m in 2010 (constant 2010 US$). Along with this increase has come a proliferation of agencies at the global level concerned to address specific health issues. Table 3 lists the key ones, starting with the landmark event of the Alma Ata conference in 1978, which launched the primary care movement. Since then, the tendency has been for more and more of the international initiatives to be focused on specific diseases – known as ‘vertical programs’ when they are organized and delivered in silos, separate from general health services. Most prominent have been HIV, TB, and malaria, but other diseases also feature, notably vaccine-preventable diseases such as polio and measles and so-called ‘neglected’ tropical diseases such as filariasis. In partial response to the attention given to these diseases, and to the resources they have attracted, other responses have developed particularly to seek remedy of the relative lack of emphasis on maternal, neonatal, and child health.

These international initiatives have very important consequences for low-income countries. Although they may provide the means to address effectively the needs of certain population groups, such as AIDs patients, they fragment the policy and planning environment at country level. Funds often flow vertically within a particular disease area, from international donors directly down to regional and local levels in a disease-specific chain of command and rarely in response to a systematic and comprehensive cross-disease planning process at country level. Low-income countries are on the receiving end of a multiplicity of funder requirements and procedures, which stretch already limited management capacity. Funders may bypass core government structures, such as central procurement agencies or indeed the Ministry of Health itself, rather than strengthening them.

Despite the growing importance of noncommunicable diseases, there are very few initiatives to address these, the framework convention on tobacco control being the only one in Table 3. An advocacy process, which resulted in a UN high level meeting on noncommunicable diseases in 2011, is generally considered to have produced very little in the way of concrete action.

Addressing Public Health In Low- And Middle-Income Countries

Concerns about the effective functioning of the health systems of low and middle-income countries have led over many years to processes of what in the 1980s and 1990s were called ‘health sector reform’ and now are more commonly referred to as health systems ‘development’ or ‘strengthening’. Such efforts can be criticized for focusing primarily on the health care system, rather than on broader public health. For example, from the 1980s onward debates have focused on the choice of policies for health financing. Advocates in international agencies, such as the World Bank, and the UK, French and German bilateral aid agencies, have taken up various positions over time on the appropriate mix of user fees for government health services, community-based health insurance schemes, social health insurance, and increased use of private financing arrangements including private voluntary health insurance. However, notably absent from the policy proposals until very recently have been statements on the critical importance of devoting increased government tax revenue to health. Given that public health above all concerns services that have the characteristics of public goods and externalities, it is apparent that planning for public health will not feature prominently when the main focus of debate is on how to stimulate sources of financing beyond government revenue.

The recent attention given by WHO and other international agencies to the ‘social determinants of health’ can be seen as an attempt to redress the balance in favor of a comprehensive and multisector approach to health. Social determinants are economic and social conditions, and their distribution among the population, that influence individual and group differences in health status. A WHO-appointed Commission on the Social Determinants of Health, set up in 2005 and reporting in 2008, examined the relationship between a variety of economic, political, legal, social and physical factors, and health. Although the report has been followed by a world conference in Rio and a WHO Executive Board resolution, it is not clear whether any low- or middle-income country has really embedded the thinking of social determinants into its government-wide public health planning. Indeed, cross-sectoral action is hard to achieve across government departments in rich and poor countries alike.

Thailand offers an innovative approach to financing public health efforts with a focus on health promotion. Borrowing from the model of VicHealth in Australia, which was originally funded by a tobacco levy, The Thai Health Promotion Foundation is funded by a surcharge on tobacco and alcohol excise taxes. It spends approximately USD$100 million a year on health promoting activities and works with a wide range of multisectoral partners. Its status as an independent public agency makes it somewhat less bureaucratic and more flexible than is the case for government departments, and its earmarked tax funding gives it important financial muscle. Although it is difficult to identify its specific impact, Thailand experienced a decline in smoking among more than 15-year olds from 25.47% in 2001 to 20.7% in 2009; a reduction in the proportion of heavy drinkers from 9.1% in 2004 to 7.3% in 2009 (as well as a reduction in household expenditure on alcohol); and a fall in death rates from vehicle accidents from 22.9 per 100 000 in 2003 to 16.82 per 100 000 in 2010.

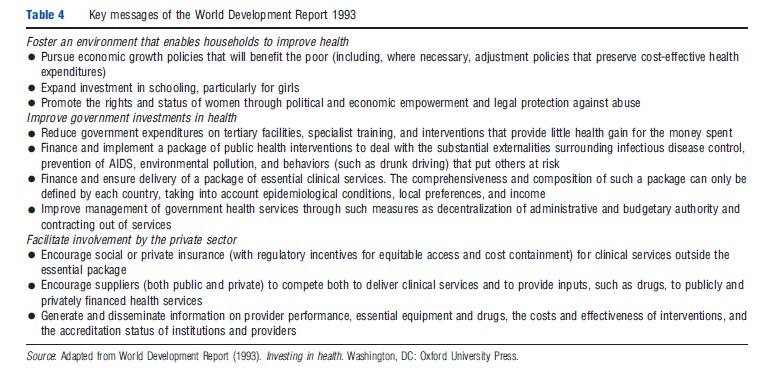

The Thai experience is very much an exception in its focus on broader public health issues. Most of the discussion on public health in low and middle-income countries has focused on interventions which address directly the health needs of individuals. It is interesting to track the evolution of this approach. In the early 1990s, there was growing concern about what was seen as the inefficiency of health expenditure patterns in low and middle-income countries. Although technical inefficiency was a concern, the debate especially focused on allocative inefficiency, with criticism of the high share of government health expenditure going on higher level hospital care when service coverage at the primary care level remained very poor. The landmark World Development Report of 1993 (WDR 93) introduced the DALY metric and analysis of burden of disease in terms of DALYs and also the notion of a ‘package’ which would respond to the largest elements of the burden. Looking back at the WDR 93, it is notable that not only there was examination of the broader context of disease which led to recommendations on fostering an environment that enables households to improve health (see Table 4), but also two packages were recommended, one of public health interventions and the other of essential clinical services. The former included public health action beyond that focused on individuals, including environmental pollution, and addressing drunk driving.

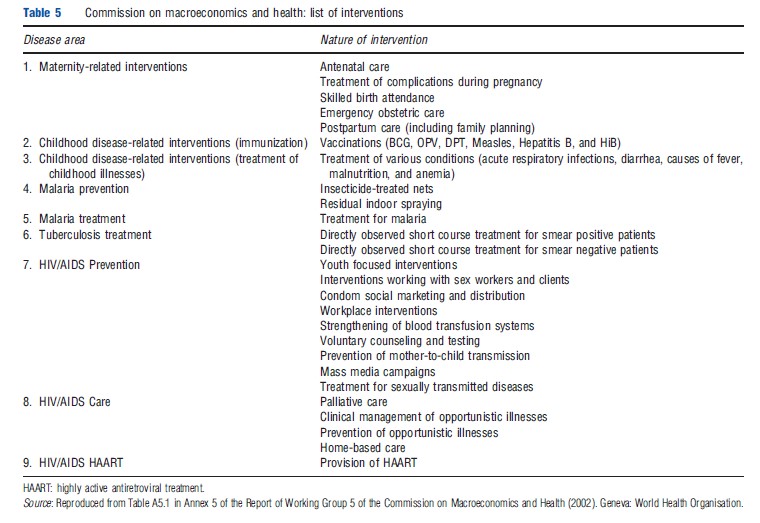

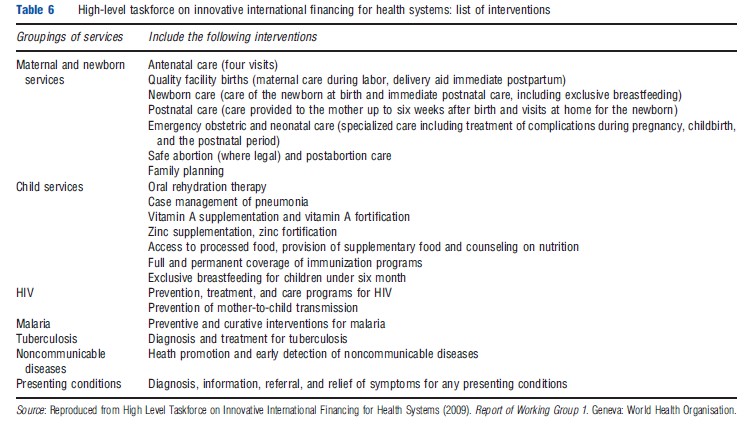

Although the approach of prioritizing a set of interventions has persisted in global health policy, the importance of encompassing both broader public health and clinical interventions seems to have been forgotten. The subsequent two developments of this approach, the WHO Commission on Macroeconomics and Health (2001) and the WHO High Level Taskforce on Innovative International Financing for Health Systems (2009), both defined sets of interventions consisting almost exclusively of those focused on individuals and households (Tables 5 and 6). The importance for health of the broader environment appears to have been forgotten. Even water and sanitation did not feature prominently, on the grounds that environmental health interventions of this kind were not considered as cost-effective for health improvement as health interventions targeting individuals.

It is interesting to reflect on the role that evaluation may have played in encouraging this development. The WDR 93 developed its dual package through analyzing both the burden of disease and the cost-effectiveness of interventions. At that time, the evidence base was weak across all areas, so much of the analysis was tentative. Since then, there has been a great increase in the volume of cost-effectiveness analysis but with a focus on specific interventions. Most commonly, the economic evaluation studies have been linked to epidemiological trials of new drugs, diagnostic methods, or more recently health service improvements. Broader public health measures lend themselves less readily to what has been perceived as the gold standard methodology of the randomized control trial. Moreover, because such measures tend to have multidimensional outcomes (both different types of health benefit as well as benefits beyond health), but only single health outcomes are usually measured, they appear less cost-effective relative to interventions focusing on specific groups of individuals.

Figure 4 Cost-effectiveness of interventions related to high-burden diseases (>35 million DALYs) in low-income and middle-income countries. Bars = range in point estimates of cost-effectiveness ratios for specific interventions included in each intervention cluster and do not represent variation across regions or statistical confidence intervals. Point estimates obtained from DCP2, calculated as midpoint of range estimates reported, or calculated from a population-weighted average of region-specific estimates reported. Only interventions with cost-effectiveness reported in terms of DALYs are included in figure. Advertising bans, smoking restrictions, supply reduction, and information dissemination. ┼Chloroquine = first line drug; artemisinin-based combination therapy = second-line drug; and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine = first-line or second-line drug. Reprinted from Laxminarayan, R., Mills, A., Measham, A., et al. (2006). Advancement of global health: Key messages from the Disease Control Priorities Project. The Lancet 367, 1193–1208.

Figure 4 illustrates the problem that broader public health measures can appear less cost-effective relative to specific clinical interventions, using analyses from the Disease Control Priorities Project. This project produced a book, which provided evidence on disease burden and intervention cost-effectiveness in 73 chapters covering specific diseases and health conditions, risk factors, consequences of disease and injuries, and clusters of services including public health, primary care, hospital care, and surgery. Figure 4 summarizes the cost-effectiveness of interventions intended to address conditions causing a high disease burden. It is striking how few broader public health measures are included in this list, the only ones being mass media aimed at reducing saturated fat intake, and legislation to influence salt, fat, alcohol, and tobacco consumption.

The analysis on communicable disease control undertaken for the first Copenhagen Consensus (www.copenhagenconsensus.com/Home-1.aspx) also illustrates the difficulties of the evidence base. The Copenhagen Consensus examines the best way to spend aid using the metric of economic evaluation. In terms of benefits relative to costs, and based on the existing evidence, control of HIV/AIDS and control of malaria had far higher benefit cost ratios than the strengthening of basic health services. But it was clear that the nature of the evidence was highly problematic. First, the available evidence for costs and effects of specific disease control measures came mainly from trials, whereas the evidence on strengthening basic health services came from cross-country analyses, which explored the relationship between public expenditure on health care and infant and child mortality rates. One would expect trials to show higher levels of effectiveness that would not be replicated in real life. Moreover, the cross-country studies captured only the health care benefits to children rather than the population as a whole (partly because the benefits of multipurpose health services are not easily captured in a single metric, whereas metrics are readily available to evaluate disease-specific trials). Thus, it is likely that the health benefits of basic health care are underestimated.

Another example of the weaknesses of current evaluation methods, and how they can bias against broader public health action, comes from the HIV literature. Evidence is now strong that HIV incidence is declining in Uganda and Zimbabwe, for example. Yet, given what is known about the effectiveness and coverage of specific interventions, this is hard to explain. It may be that there are synergies among interventions that existing research does not capture; or that there are broader social influences at work (e.g., much greater individual awareness of the risk of HIV as a result of knowing close friends and relatives dying from HIV and behavior change as a result). These again are difficult to capture using traditional evaluation methods.

Awareness is growing of the ways in which evaluation methodologies risk distorting policy choices, especially with the increasing emphasis on requiring policy makers to base their decision making on high-quality evidence. Methods for economic evaluation need to develop beyond their current focus on single intervention approaches and single measures of outcome

Conclusions

This article has sought to examine some of the specific issues concerned with improving public health in resource poor settings. Its prime conclusion is that a number of influences have led to the broader determinants of health, those that can be addressed by public health action beyond personal health services, being grossly neglected. It is critical that planning and evaluation move beyond their current health care and disease specific focus, not least given the looming threat of noncommunicable disease and the need to address its root causes. This will require innovations in research and evaluation methodology, as well as remedying the current global bias to control of specific diseases rather than broader health improvement.

A further challenge will be the changing global dynamics of relations between richer and poorer countries. Already China and India have graduated from low-income country status. In Africa, economic growth prospects now look brighter, especially given Africa’s mineral resources. Traditional financial development assistance is likely in the longer term to decline as a source of influence on health policy. Expertise and knowledge will increasingly be of more use to the developing world than cash. Public health institutions for generating knowledge and acting on it will need to develop and evolve both globally and nationally if past health gains are to be sustained and new health risks tackled.

References:

- Commission on Macroeconomics and Health (2001). Macroeconomics and health: Investing in health for economic development. Geneva: World Health Organisation.

- Dasgupta, P. (2007). Macroeconomic history. Economics: A very short introduction, ch. 1, pp. 1–29. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kelly, M. P. and Doohan, E. (2012). The social determinants of health. In Merson, M., Black, R. and Mills, A. (eds.) Global health. Diseases, programmes, systems and policies. Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett.

- Laxminarayan, R., Mills, A., Measham, A., et al. (2006). Advancement of global health: Key messages from the disease control priorities project. The Lancet 367, 1193–1208.

- Macfarlane, S., Racelis, M. and Muli-Musiime, F. (2000). Public health in developing countries. The Lancet 356, L841–L846.

- Mills, A. (2011). Health Systems in low- and middle-income countries. In Glied, S. and Smith, P. C. (eds.) Oxford handbook of health economics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- The Lancet (2012) The Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet 380, December 15/22/19, 2012.

- Walt, G., Buse, K. and Harmer, A. (2012). Cooperation in global health. In Merson, M., Black, R. and Mills, A. (eds.) Global health. Diseases, programmes, systems and policies. Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett.

- World Development Report (1993). Investing in health. Washington, DC: Oxford University Press.