Recent work in economics suggests that adverse health shocks experienced in utero can have long-lasting effects. Studies have linked fetal health to a variety of outcomes in adulthood, such as schooling, labor market activity, and mortality. These studies have also identified a broad array of ‘nurture shocks,’ including ambient pollution levels, infectious disease, and mild nutritional deficits, that can generate long-lasting consequences.

The fact that maternal health has such important consequences for the child stands in stark contrast to conventional medical wisdom of the early twentieth century, which held that the womb effectively protects the fetus. For example, during the 1950s and 1960s, expectant mothers were routinely told it was fine to drink and smoke. Policymakers felt there was little cause to aim health policy at pregnant women.

Recent findings by economists on the fetal origins of adult outcomes should help change policymakers’ focus. Environmental regulation that decreases the exposure of pregnant women to pollutants, for example, may have important ramifications on the educational attainment of their children. However, understanding the exact mechanisms that tie fetal health to later-life outcomes remains a developing area of research.

Early Evidence

The ‘thalidomide episode’ in the late 1950s and early 1960s was a watershed event in establishing the importance of the in utero period. Thalidomide was licensed in 1957 and widely prescribed to pregnant women for morning sickness until 1961, when it was identified as the cause of an epidemic of severe birth defects such as missing arms and legs. This episode revealed that the fetus was more vulnerable than previously thought, and led researchers to wonder: Could shocks to maternal health have other long-term health effects?

Several aspects of this historical episode facilitate analysis of the causal effects of fetal malnutrition. First, the famine was unexpected, so the Dutch were unable to stock up on food or leave the country in anticipation. Second, it was sudden, meaning that researchers can clearly identify which children were in utero during the famine versus those that were unaffected. The fact that food supply was adequate beforehand means that children born shortly before the famine serve a good control, or comparison, group. Finally, famines tend not to occur in countries with good vital statistics data systems in place, the Netherlands being an important exception.

Epidemiologists found widespread effects of the ‘Hunger Winter’ on maternal and fetal health. These studies show that the famine affected fertility, weight gain during pregnancy, maternal blood pressure, and infant birth weight. Results on the long-term effects on children in utero during the famine were initially somewhat mixed, in part because birth weight did not always seem to mediate the long-term damage (as many expected). As the affected birth cohorts aged, a more consistent pattern of adult health damage has emerged, including chronic health conditions like coronary heart disease, glucose intolerance, hypertension, and obesity.

Motivated by this evidence (and perhaps the initial controversy surrounding it) economists wondered whether adverse conditions in utero might: (1) affect outcomes traditionally studied in economics, such as schooling, employment, wages, and retirement, and (2) extend to a broader range of in utero environmental influences.

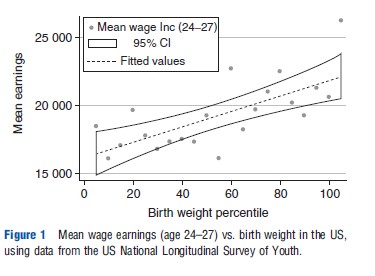

In Figure 1, wage earnings are plotted against birth weight using data from the US National Longitudinal Survey of Youth. This survey began with young people between the ages of 14 and 21 in 1978. Children born to women in this cohort have now been followed into young adulthood. As the figure shows, there is a positive correlation between birth weight and mean earnings. Descriptive findings like this encouraged economists to believe that there might be a causal relationship between fetal health and human capital.

The finding that test scores were lower in low-birth weight children was surprising as epidemiologists had posited fetal ‘brain sparing’ mechanisms, whereby adverse in utero conditions were parried through a placental triage that prioritized neural development over the development of other parts of the body.

Economists have subsequently explored the idea that fetal insults manifest later in life with numerous studies. In these studies, economists such as Janet Currie, Douglas Almond, and Michael Greenstone have looked at both the effects of large natural experiments, like the ‘Hunger Winter,’ as well as smaller, every-day shocks, such as pollution. Some studies compare across siblings – where one is affected by the shock but the other is not – whereas others compare across affected and unaffected cohorts. Before these studies are reviewed, a simple framework to help organize concepts will be discussed.

Conceptual Framework

One reason economists have become interested in the fetal origins hypothesis is that it holds important implications for the modeling of human capital development. In the classic health production framework, developed in 1972 by economist Michael Grossman of City University of New York, health behaves like a physical stock that serves as both an investment good and a consumption good. In this classic framework, the impact of shocks to the stock of health fades away over time. This model is applicable to many scenarios – if a child suffers a broken bone, it can heal as time passes. More formally, the formula for the health stock at time t in Grossman’s model is often written as:

![]()

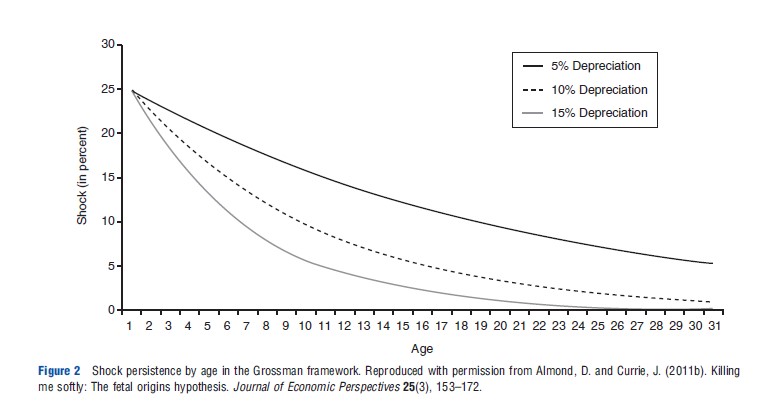

where It represents investments in health capital and d represents the depreciation rate. So, if health capital depreciates and is responsive to new health investments, then the effects of shocks to health capital tend to also depreciate over time, so that events further in the past will have less-important effects than more recent events.

Figure 2 shows how persistent a 25% negative shock to the birth endowment would be given alternative annual depreciation rates d. Even under the lowest annual depreciation rate of 5%, half of the endowment shock is gone by the mid-teen years. For the higher depreciation rates of 10% and 15%, one would be hard-pressed to detect any lingering effects of the shock after age 30.

More formally, in the simplest two-input constant elasticity of substitution model capital and labor inputs are replaced with investments in utero and those occurring during the rest of childhood, writing:

![]()

By allowing for varying complementarities between investments in different periods, the model is able to generate a number of rich theoretical predictions. If fetal and childhood health are complements, for example, this underscores the persistent importance of a ‘good start,’ as opposed to the ‘fade out’ implication of the Grossman model. This would occur, for example, if healthier newborns benefit more from breastfeeding or other nutrition. An extreme version of this technology includes perfect complementarity, whereby investments made in utero restrict the maximum level of lifetime capacity. Further, by allowing different dimensions of capacity to affect the productivity of investment, cross-capacity complementarities can shape investment decisions. For example, one might expect good childhood health to facilitate the development of cognition.

Empirical Evidence

Empirical evidence shows that investments in early childhood explain much of the variation in adult health. An intuition is that if early investments are especially effective and have had a longer time to feed through the dynamic system, their effect might be especially persistent. That said, it may be useful to distinguish conceptually between an early-life health shock and responsive investments: actions made in response to health shocks. What is observed in adulthood combines the effect of the shock and the responsive investments, should they exist. For example, there may be individual or institutional responses to health shocks, such as government aid following an earthquake. Importantly, families may provide investments that either remediate or reinforce shocks experienced in utero. Hence, when examining longer-term outcomes, it is important to keep in mind that these can represent both biological and social factors.

The 1918 Influenza

An influential study in the field of fetal origins research is Douglas Almond’s paper on the 1918 Influenza Pandemic. Almond, a Professor of Economics at Columbia University, linked in utero exposure to the Influenza Pandemic to deteriorations in human capital accumulation and labor market activity decades later. Like the Dutch ‘Hunger Winter’ associated with the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands the Influenza Pandemic was sudden, short, unexpected, and widespread, providing an appealing research design.

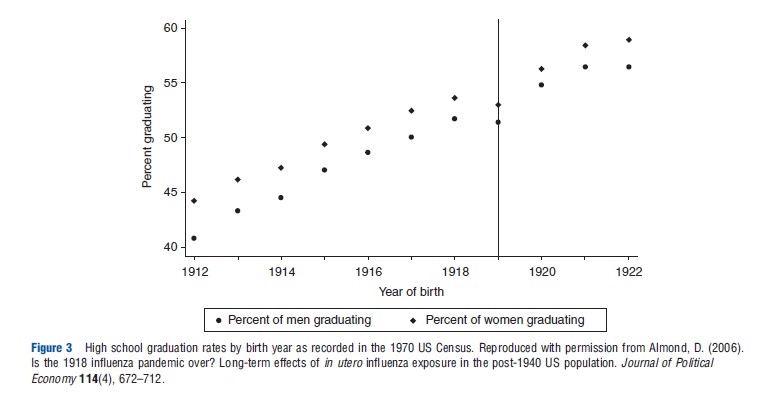

Almond used data from the US Census, which record quarter of birth in some decades, to identify which infants were exposed to the flu. Although the Census does not tell us which mothers were infected, the flu was widespread enough that roughly one-third of infants born in early 1919 had mothers who contracted influenza while pregnant. As a control group, those born in early 1918 had essentially zero prenatal exposure to the 1918 pandemic. Figure 3 shows the high school graduation rates by birth year as recorded in the 1970 Census.

Further, Almond also used variation across US states in the severity of the pandemic to construct a second, difference-in-differences estimate of the pandemic’s effect. Both econometric approaches yield large estimates of long-term effects. Despite the brevity of the health shock, children of infected mothers were approximately 20% more likely to be disabled and experienced wage decreases of 5% or more, as well as reduced educational attainment. These results have now been replicated using data from other countries including Great Britain, Brazil, and Taiwan.

Identification

The fact that the fetal origins hypothesis applies to a well-defined developmental period means that it lends itself well to testing. In particular, the hypothesis predicts that later-life health outcomes should be worse only for those cohorts whose pregnancies overlapped with the shock. This means that economists can compare outcomes among these affected cohorts against two other cohorts: the cohort that was about to be conceived when the shock occurred (and is therefore too young to be affected) and the cohort that was already born at the time of the shock (and is therefore too old to be affected prenatally).

Still, seeking to quantify in utero effects through such comparisons gives rise to several problems. First, most birth cohorts are neither exposed to an identifiable shock in utero, nor were born just before or just after such a shock (and thus cannot serve as good controls). Rather than looking at all the data on births, the researcher is immediately pushed to looking at particular episodes in which an identifiable shock occurred and then attempting to draw defensibly generalizable conclusions from these episodes.

Second, the ideal shock would be shorter than the length of gestation, so as to differentiate between fetal and earlychildhood exposure and perhaps stages of gestation. Many important prenatal factors, however, may last longer than pregnancy or may indeed shift permanently (e.g., the beginning of the US Food Stamp Program during the 1960s). The effect of fetal exposure may still be identified but constitutes the additional effect on top of any early-childhood effects. In general, it can be more challenging to isolate the effect of ‘early-childhood’ exposure because it is both less well defined and longer than the prenatal period.

Finally, one needs to be able to link data on adult outcomes to data on the affected cohorts. Economists have been creative in linking large-sample cross-sectional datasets back to ecological conditions around the time of birth. Most often, they have used information on when and where a respondent was born to link that person back to in utero health conditions. This has enabled economists to consider historical events featuring relatively well-defined start and/or end points. But many prominent datasets, such as the Current Population Survey, do not include information on where someone was born or the precise date of birth. As a result, many interesting and policy-relevant experiments linked to a certain time and place may never be analyzed.

In the next section, the empirical evidence in the context of these issues will be discussed.

Evidence From Sudden Shocks

A number of studies use sudden shocks like the 1918 Influenza to study the fetal origins hypothesis. These types of episodes often provide clean identification through sharp timing and, if far enough in the past, allow the researcher to examine outcomes over the full life course, including mortality. A drawback is that predictions associated with large-scale or historical events may be difficult to generalize.

Large-scale shocks that have been studied in association with fetal origins include: a prenatal iodine supplementation program rolled out across Tanzania in the 1980s (by Field and colleagues), radioactive fallout from Chernobyl (by Almond and colleagues), and ambient temperature and rainfall shocks during pregnancy (by Maccini and Yang and colleagues). Outcomes examined include many different measures of health and human capital.

Identification in these studies is often based heavily on birth timing vis-a`-vis the shock. Where possible, robustness is assessed by comparing effects within a certain time period across locations that experienced differing severities of the shock. Thus, the researcher is able to control for seasonal events that might coincide with the timing of the shock. Further, some datasets include a sibling link, allowing the researcher to control for fixed characteristics of families, including selective uptake of the treatment, though it is of course possible for parents to treat some siblings differently than others.

The studies referenced above produced a number of interesting findings. For example, the study on iodine supplementation found large and robust educational impacts – on average approximately half a year of schooling, with larger improvements for girls. Health measures, in contrast, appeared to be unaffected by this intervention. Subsequent work by Adhvaryu and Nyshadham has considered whether postnatal investments made by parents seem to respond to the iodine supplementation program, finding that parents reinforce iodine-related cognitive increases. Similarly, Chernobyl radiation in Sweden seems to have had its largest impact on human capital formation, not on health per se, suggesting the possibility of parental response to health endowment at birth.

Longer Natural Experiments

Many potential pathogens are more persistent than the shocks considered in Section Evidence from Sudden Shocks. Recent research has sought to maintain identification while considering slower-moving experiments, for example, to ambient pollution levels. Empirical evidence shows that these insults often have large effects on fetal health. Such findings are of particular interest because these exposures are often more common and generalizeable than with sudden shocks. A case in point is to consider the impact of slower-moving climate change as opposed to weather shocks, where adaptations and responses may differ.

As before, studies have also considered longer-term changes in the infectious disease burden. Infections can affect fetal health by diverting maternal energy toward fighting infection, by restricting food intake, or through negative consequences arising from the body’s own inflammatory response. These studies have exploited variation in infectious disease in the US across seasons and states, including policy-related improvements in malaria in South US. Results show that reductions in infectious disease in utero lead to improvements in mortality and schooling later in life. For example, estimates show that early-life malaria can account for a quarter of the difference in long-term educational attainment between cohorts born in malaria-afflicted states and non-afflicted areas in the early twentieth-century US.

There is evidence that some milder health shocks such as relatively low-level exposures to every-day contaminants as automobile exhaust and cigarette smoke also have negative effects on fetal health (see studies by Janet Currie, Michael Greenstone, Kenneth Chay, and others). Yet there has been little research to date linking fetal exposures to future outcomes. An exception is a study by Saunders that links the US recession of the early 1980s to reduced pollution and, through increased fetal health, improvements in high school test scores years later. Pollution levels experienced by these cohorts were high when compared to today but low when compared to many developing countries, such as China.

Studies found that being in utero during the annual Ramadan fast is associated with a broad spectrum of damage later in life, both to health and human capital. Daytime fasts that fall during early pregnancy have been found to have particularly large effects, despite being relatively mild when compared to famine events previously analyzed. This effect may arise because some pregnant women may fast without knowing they are pregnant.

Finally, a number of recent papers consider the effects of aggregate economic conditions around the time of birth on fetal health. Here, health in adulthood tends to be the focus (rather than human capital), and findings are less consistent than in the studies of nutrition and infection described above. One problem may be that the shocks are more diffuse in terms of timing so comparisons are less sharp. (A notable exception considers the effect of income shocks from crop blight across France.) A second issue is that the mechanism is less clear as economic downturns may affect fetal health through multiple pathways including effects on nutrition, smoking, and stress. Research by Van Den Berg and colleagues found that those born during economic downturns in the Netherlands had shorter lives, whereas a study by Cutler and colleagues on cohorts born during the Dust Bowl era in the US did not find any long-term effects.

Further Issues: Measurements Of Fetal Health

All of the previously discussed studies show this maternal health shocks can be transmitted to the fetus. The most commonly used measure of fetal health is birth weight, but it may not be a particularly comprehensive or sensitive measure. In studies of the Dutch famine, for example, cohorts who were exposed to famine during the first half of pregnancy were found to have relatively normal birth weight but later showed evidence of health effects such as incipient heart disease.

Birth weight is, however, the most widely available measure of fetal health and there has been no convergence on an alternative, superior measure. An ideal metric would be sensitive for (even latent) fetal insults at all stages of pregnancy, be easy to measure, and be available for all mothers (or at least a large sample of mothers) in a cohort at the time of birth. Finding this measure of health at birth would obviate the need for data on later-life outcomes, enabling the researcher to examine current shocks rather than having to focus on those far in the past.

The lack of an ideal measure of fetal health has not, however, prevented economists from addressing the fetal origins hypothesis. This may be because economists are accustomed to considering many variables to be latent – like the potential wages of non-workers. On a practical level, economists’ focus on identification strategies enables them in many circumstances to sidestep the question of finding a better measure of fetal health.

Further Issues: Bias From Selective Prenatal Mortality

A final issue to beconsidered is that of fetal mortality. Depending on the severity of a given shock, it may be that some fetuses die in response. Given that this type of selective mortality is unobserved in most birth data, researchers may underestimate fetal health shocks if the fetuses with higher baseline health are the ones that survive (but are ‘scarred’). This becomes a serious problem if the negative scarring effects are sufficiently strong among the survivors to overwhelm the positive effects of selection.

Although this issue has been acknowledged outside of economics, economists have contributed by devising ways to model unobserved fetal mortality somewhat more formally. Such an exercise can be used to help quantify the selective effect due to mortality, and thereby isolate the ‘scarring’ effect of prenatal health conditions.

Conclusion

This article has summarized the current state of economics research on the fetal origins hypothesis. This hypothesis states that many important adult health and labor market outcomes may originate with fetal health conditions. Leveraging large-scale datasets and the sharp predictions associated with in utero exposure, economists have confirmed the link between fetal health and later-life outcomes. These results may hold true not only for large shocks but also for relatively mild and common shocks, such as reductions from already relatively low levels of air pollution and seasonal infections. Understanding the exact propagation mechanisms and how best to design remedial policies remain important research areas.

Acknowledgement

Almond was supported by NSF CAREER award #0847329.

References:

- Almond, D. (2006). Is the 1918 influenza pandemic over? Long-term effects of in utero influenza exposure in the post-1940 US population. Journal of Political Economy 114(4), 672–712.

- Almond, D. and Currie, J. (2011a), Human capital development before age five. In Ashenfelter, O. and Card, D. (eds.) Handbook of labor economics, ch. 15, vol. 4b, pp 1315–1486. North Holland: Elsevier.

- Almond, D. and Currie, J. (2011b). Killing me softly: The fetal origins hypothesis. Journal of Economic Perspectives 25(3), 153–172.

- Barker, D. J. (1990). The fetal and infant origins of adult disease. BMJ 301(6761), 1111.

- Black, S. E., Devereux, P. J. and Salvanes, K. G. (2007). From the cradle to the labor market? The effect of birth weight on adult outcomes. Quarterly Journal of Economics 122(1), 409–439.

- Chay, K. Y. and Michael, G. (2003). The impact of air pollution on infant mortality: Evidence from the geographic variation in pollution shocks induced by a recession. Quarterly Journal of Economics 118(3), 1121–1167.

- Currie, J. and Rosemary, H. (1999). Is the impact of shocks cushioned by socioeconomic status? The case of low birth weight. American Economic Review 89(2), 245–250.

- Currie, J., Stabile, M., Manivong, P. and Roos, L. L. (2010). Child health and young adult outcomes. Journal of Human Resources 45(3), 517–548.

- Grossman, M. (1972). On the concept of health capital and the demand for health. Journal of Political Economy 80(2), 223–255.

- Heckman, J. J. (2007). The economics, technology, and neuroscience of human capability formation. PNAS: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104(33), 13250–13255.

- Kermack, W. O., McKendrick, A. G. and McKinlay, P. L. (1934). Death-rates in Great Britain and Sweden: Some general regularities and their significance. Lancet 31, 698–703.