There is an established ‘healthy public policy’ agenda concerned with the social determinants of health, which recognizes that nonhealth sectors of public policy often have greater impacts on population health and health inequalities than health sector policies. This political agenda has been promoted by the World Health Organization (WHO) since the 1980s (see Box 1), and has led to a widening of the definition of public health interventions to include nonhealth sectors.

In line with this agenda, there are increasing calls for economists to help generate evidence that investing in the social determinants of health, for the explicit purpose of improving health and tackling health inequality, can represent good value for money. To date, however, health economic research in this area is relatively limited. This article reviews existing economic principles and methods of priority setting, and discusses how they can most fruitfully be applied to support the ‘healthy public policy’ agenda. The discussion focuses on supporting this agenda at the local government level (e.g., city or state level), which has important impacts on the social determinants of health, yet has hitherto received particularly limited attention by health economists. However, the economic principles and methods reviewed can of course also be applied to public policy making at national and supranational levels.

The section The Scope of the Challenge: The Social Determinants of Health illustrates the challenges faced inpublic health, where interventions that have major impacts on health originate from multiple policy sectors and are led by decision makers are primarily motivated to deliver specific nonhealth outputs such as new housing. Intersectoral impacts are a common feature of most public policies; health is not a special case in this respect. Therefore, the wider challenge is how to encourage different policy sectors to consider and value all major intersectoral impacts of importance to society as a whole, including health.

The section How to Encourage Intersectoral Alignment: the Role of Economic Evaluation describes how economics is well-placed to encourage intersectoral coordination by developing the economic evidence in order to identify, measure and value the intersectoral spillovers of policies and the overall impact on social welfare. It begins by offering a brief primer on the economic way of thinking about priority setting. It emphasizes that a distinctive advantage of the economic way of thinking is its ability to adopt a broad societal perspective, which considers how best to allocate scarce resources to improve overall social welfare, making appropriate tradeoffs between different and potentially conflicting social objectives. Economics is thus not constrained to a narrow focus on one particular outcome or objective, such as improving health or reducing health inequality, but is capable of combining multiple objectives into the same analysis. Therefore, the scope of ‘healthy public policy’ fits naturally within an economic approach. The practical challenge is to engage with decision makers both to address sector specific concerns and to identify areas where further coordination can improve social welfare.

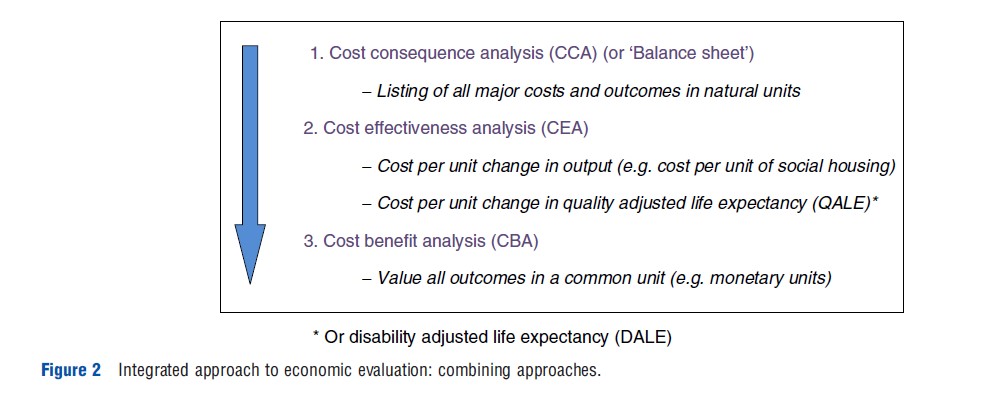

The article then considers appropriate approaches to economic evaluation and contends that the best approach is to combine cost consequence (CCA), cost effectiveness (CEA), and cost benefit analysis (CBA). This would account for and report all major intersectoral impacts, including health, and value these impacts in terms of net social welfare. It then reviews standard economic tools for priority setting and discuss their potential role in helping to coordinate different policy sectors, frame the decision process, make explicit stakeholder objectives, and translate economic evidence into policy. Taken together, the sections on economic evaluation and priority setting tools lay out an ‘integrated societal framework’ to enable all impacts to be accounted for, valued, and taken into consideration by decision makers.

The section Translating Evidence into Policy: The Role of Priority Setting Tools briefs how economic evidence can then be used by decision makers. It reviews standard economic tools for priority setting and discusses their potential role in helping to coordinate different policy sectors, frame the decision process, make explicit stakeholder objectives, and translate economic evidence into policy. Taken together, the sections on economic evaluation and priority setting tools lay out an ‘integrated societal framework’ to enable all impacts to be accounted for, valued, and taken into consideration by decision makers.

The Scope Of The Challenge: The Social Determinants Of Health

The Rise Of The ‘Healthy Public Policy’ And ‘Social Determinants Of Health’ Agendas

Alongside the political agenda for ‘healthy public policy’, there is also an established research agenda regarding the social determinants of health, with contributions from a number of eminent scholars from different disciplines. Much of this research from outside the discipline of economics has been usefully collated in the 2008 report of the WHO Commission on the Social Determinants of Health; though this report does not offer comprehensive coverage of economic contributions to theory and evidence on this topic.

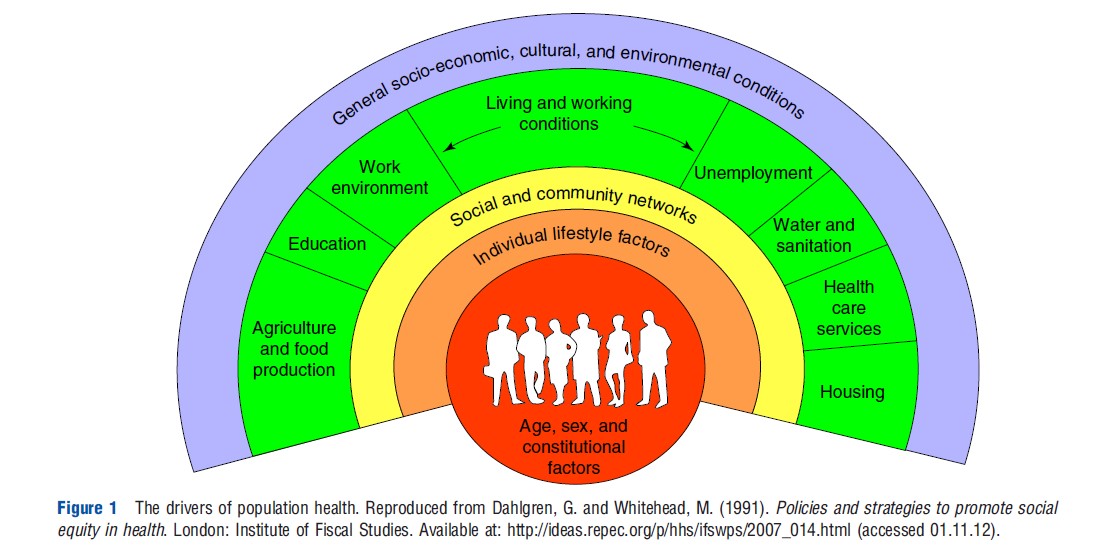

Public health interventions can impact on health directly through the provision of public goods, such as water and sanitation; or through changes in legislation, such as environmental standards or food industry regulations. Other sectors also impact on health indirectly by influencing the willingness and ability of communities and individuals to invest in health, for example, through behaviors like healthy eating. For instance, education in childhood influences aspirations and future adult employment, which may in turn provide the means for individuals to invest in themselves and their children. Further, community interventions such as housing and regeneration may offer an incentive to invest in and protect neighborhoods from crime and antisocial behavior, which may be especially harmful for childhood development. Figure 1 attempts to summarize the wide array of drivers of population health. The diagram is limited in that the interaction between the various drivers is not captured and nor is the life-course, where an individual’s early years development can influence their future adult outcomes. Nonetheless, it is a commonly used and helpful illustration that health is not simply the product of healthcare.

As a consequence, a ‘healthy public policy’ agenda has emerged, which may be crudely described as an advocacy movement. The contention is that interventions from nonhealth sectors should be thought of as ‘upstream’ public health interventions, which can have larger impacts on population health and health inequalities in the long run than health sector interventions.

A particular concern of the ‘healthy public policy’ agenda is that health impacts are still not being (fully) considered when nonhealth sectors make decisions. Further, in times of fiscal tightening, when public sector budgets are being reined in, policymakers understandably concentrate on short-term priorities such as the provision of amenities that are currently and visibly in high demand from voters and interest groups, which may then be detrimental to long run goals of improving population health and reducing health inequalities.

In recent years, there have been growing calls for economists to engage more fully with this agenda to generate economic evidence on which investments in the social determinants of health represent the best value for money.

Engaging With The ‘Healthy Public Policy’ Agenda: The Need For Intersectoral Alignment

In considering how best economists can engage with the ‘healthy public policy’ agenda, there are three important observations. The first is that decision makers are primarily incentivized to deliver sector specific outputs. Health outcomes, if considered at all, are byproducts and not the main priority of nonhealth sectors. Second, intersectoral impacts are a common feature of most policies. Third, health is nevertheless an outcome of particular importance for social welfare, which people value both as a consumption good and as an investment good that allows them to lead flourishing lives and act as productive members of their family and of the wider economy and society.

Taken together, these observations suggest that simply advocating to nonhealth sectors the importance of considering the health consequences of policies may not be enough to influence decision makers. There is a need to generate a ‘quid pro quo’ to incentivize decision makers to consider health impacts. A productive way forward may be for all sectors to be encouraged to move beyond narrow sector perspectives to consider all major intersectoral impacts. Consequently, the challenge is not simply ‘how can we persuade nonhealth sectors to produce health outcomes?’ but ‘how can we help coordinate and align sectors where health is valued as one important input toward achieving the common overall aim of increasing social welfare?’

Opportunity For Intersectoral Alignment: Local Decision-Making

Before considering how economics can help the ability of decision makers to coordinate, it is important to identify whether decision makers have the willingness to do so. This short section discusses where economists may have the most immediate opportunities to improve policy coordination.

It can be helpful to distinguish multiple policy ‘levels’ that drive health, including: international, national, regional, and local. However, these levels are not necessary strictly demarcated, and there are interactions between them. At the international level, major drivers include global warming and trade legislation. At the national level, the fiscal allocation of resources to spending departments is an important issue, and there is a dialog at the national level, which is synchronized with political cycles where spending departments bid for funds. Government economists are typically closely involved in this process. These national and international issues are important but not the focus of the present discussion. Rather, the focus is on the local level of decision-making (e.g., local authority, state, and city), an area that health economics has paid relatively little attention to, thus far.

Local decision makers increasingly have a culture where different sectors and agencies operate together in partnership working. This provides a real opportunity for ‘horizontal’ coordination across sectors (and ideally ‘vertical’ coordination between levels of the system). For instance, the Public Health Agency of Canada has expanded its remit from coordination of interventions to prevent infectious disease outbreaks, to developing a vision that seeks to harness the social determinants of health to protect, maintain, and improve population health, more generally.

Policy coordination needs supporting institutional structures. There are promising examples from across the world that this is happening. For instance, in the UK, the Department for Health in England has devolved responsibility for public health to local levels with budgets being transferred accordingly. Public health can now be considered along with the wide range of other public sector concerns. Existing decision-making forums, such as ‘One Place,’ can also facilitate the development of common objectives that all sectors work toward. Another example is an innovation in Scotland called the Single Outcome Agreement, which provides joint targets that policies need to demonstrate progress against. A third example is the 2009 Australian National Partnership Agreement on Preventive Health. This illustrates the use of a national-level institutional structure to support local public health policy coordination, encouraging both horizontal coordination between sectors and vertical coordination between local and national levels.

The emerging notion of a ‘systems approach’ to public health policy-making recognizes the multiple social determinants of health, and the interaction between policies, and looks for better ways to coordinate. For instance, health inequalities are the result of a system of influences, in which social disadvantages often cluster on the same groups in society, such as poor education, low employment, poor housing, and high rates of crime. It has therefore been argued that policies to reduce health inequalities should be developed (and evaluated) as ‘multisectoral packages’ rather than ‘sector specific interventions.’

How To Encourage Intersectoral Alignment: The Role Of Economic Evaluation

The Need To Take A Societal Perspective In Evaluation

From first principles, the fundamental problem economics is concerned with is scarcity: wants are infinite, but means are finite. The overarching purpose of normative economics is to inform the allocation of scarce resources with a view to improving ‘social welfare’ (variously known in other disciplines and contexts as ‘social value’, or ‘the social good’, or ‘the public interest’).

Prioritization is inevitable and normative economics is concerned with how to do this explicitly and rationally, given the information available. According to one of the founding fathers of health economics, Anthony Culyer, economic analysis ought to:

‘‘…identify relevant options for consideration; enumerate all costs and benefits to various relevant social groups; quantify as many as can be sensibly quantified; not assume the unquantified is unimportant; use discounting where relevant to derive present values; use sensitivity analysis to test the response of net benefits to changes in assumptions; and look at the distributive impact of the options’’

Therefore, the challenge of greater intersectoral alignment, discussed previously, is congruent with the first principles of health economics.

An Integrated Approach To Economic Evaluation: Combining ‘Broad’ And ‘Narrow’ Approaches

The approach outlined by Culyer fits most comfortably within the general method of economic evaluation known as ‘CBA,’ which seeks to quantify all relevant social costs and benefits, and value them in the common currency of money. However, the practical reality is that decision makers in particular policy sectors are not primarily incentivized to make decisions purely on the basis of increasing general social welfare. Therefore, simply reporting net social welfare impacts is not ideally suited for decision makers. Therefore, the challenge is to take an approach to economic evaluation that satisfies the immediate sector specific concerns of decision makers, but also demonstrates the wider impacts of decisions and pinpoints where better coordination can lead to improvements in social welfare.

It is suggested here that an integrated approach to economic evaluation should be taken, where different approaches can be seen as complementary, rather than necessary competing. The starting point could be to undertake a CCA, which is essentially a social accountancy exercise, detailing the major impacts that result from an intervention. Economists can then use the CCA to develop the outcomes that different end-users are interested in Figure 2.

First, as the funding sector(s) may be primarily interested in the provision of specific outputs or amenities, the economic evaluation can take a ‘narrow’ CEA approach and simply report cost per unit of output – for example, cost per unit of social housing of a required standard. This evidence can be used to inform technical efficiency; to identify interventions that provide a certain output, at least cost.

Second, the consequential impacts on health can be evaluated within a CEA that focuses on a generic measure of health. The CCA could include a relevant generic health related quality of life (HRQoL) questionnaire, such as SF-12 or EQ-5D measuring how HRQoL has changed following an intervention(s) on a ratio scale between 0 (for zero health) and 1 (for full health). Responses are then weighted, by population pReferences: regarding the desirability of different states, to generate a single score of ‘preference-weighted’ HRQoL. This summary score is sometimes referred to as a ‘health utility’ and can be used on its own in evaluation, or used to weight length of life to generate quality-adjusted life-years, or disability adjusted life expectancy.

Third, a CBA can then be conducted, which values all major outcomes detected in the CCA to then estimate net social benefit. The most common approach in CBA is to value all outcomes in financial terms. This ‘broad’ approach is then intended to estimate the overall social worth of alternative interventions.

Overall, combining approaches (CCA, CEA, and CBA) would have the strength of explaining how different stakeholder interests are related to one another, and how they are valued as part of overall social welfare. In this respect, the approaches of CCA and CEA can be seen as ‘nested’ within the overall framework of CBA.

It is important to recognize that producing economic evidence is only the first step in how economists can influence priority setting. The next step is to help decisionmakers to translate evidence into policy.

Translating Evidence Into Policy: The Role Of Priority Setting Tools

This penultimate section first explains why economic evaluation, while necessary, is rarely sufficient for decisionmakers when setting priorities: economic evidence is only one consideration. It then discusses how economists can help frame the priority setting process, helping to bring stakeholders together to articulate objectives, intervention options and value judgements. Crucially, this process should articulate decision-making criteria, so that economic evidence can then be used systematically alongside other relevant considerations.

The Two Key Principles In Priority Setting

There are two key economic principles that underlie priority setting from an economics perspective. The first is ‘opportunity cost’: when investing resources in one area, the most relevant cost for the decisionmaker to consider is the opportunity for benefit that is forgone because those resources are not invested elsewhere. The second is that of the ‘margin’: when changing the resource mix, the most relevant costs and benefits for the decisionmaker to consider are the marginal costs and benefits resulting from the proposed change in the resource mix, rather than the average or total costs and benefits of all the historical resources used. The concept of the margin is important regardless of whether budgets are changed or remain the same. If additional resources are made available, the key is to use the evidence to invest in the options offering best value. If the budget is decreasing, then the challenge is disinvestment, and budget should then be taken from interventions that provide the least value. Even with static budgets, there may be scope for reallocation to produce outcomes more efficiently. Economic evaluation is intended to provide this information to make explicit the costs and benefits of alternative courses of action, and the impacts of shifting resources at the margin. However, rarely will economic evidence be immediately translated into decisions. It is important to discuss why this is the case.

Economic Evidence Is Necessary But Not Sufficient For Priority Setting

For economic evidence to be sufficient for policymakers to use as the sole basis for making policy decisions, five conditions would need to be satisfied. First, the decisionmakers involved would need to clearly articulate and agree on the policy objective(s). This then would allow economists to develop an appropriate generic outcome measure, which all alternative courses of action can be measured against. Second, the valuation of outcome measure(s) would need to incorporate all relevant ethical considerations for decision-making, including considerations of fairness or equity as well as considerations of efficiency in maximizing the sum total of social benefits net of social opportunity costs. Third, the methods used by economic evaluation would need to be fully trusted by decisionmakers. Fourth, there would need to be no additional political constraints on decisionmakers beyond considerations of efficiency and equity. Fifth, economic evidence would need to be available to use. If these conditions were satisfied, then the role of policymakers would be largely passive. That is, once the initial objectives were articulated, economic evaluation could then produce a final all-thing-considered policy recommendation, which could determine the policy decision.

These conditions are unlikely to hold in practice. First, given that the scope of public health is multisectoral, there are likely to be competing objectives and value judgements. Different stakeholders are incentivized to produce different outputs. Second, equity has not been properly addressed in economic evaluation so far. Rather, units of benefit are typically valued equally regardless of which groups in society are affected. This is clearly a problem for public health, where many interventions are in fact delivered primarily in an attempt to reduce inequality (e.g., social housing for deprived communities). This suggests that a unit of benefit for a deprived individual can in some contexts be valued higher than the same unit of benefit for a less deprived individual. Third, decisionmakers typically lack the specialist expertize to fully understand economic evaluation methods and findings, and as a result may view economic evidence with suspicion. This is an area of contention, however. Distilling the impacts of an intervention into a single index is important to enable direct comparison of the impacts of different interventions, but perhaps economists need to improve the communication with decisionmakers to foster greater trust and reliance on the academic peer review process to ensure that methods are appropriate and fit-for-purpose. Fourth, decisionmakers often have to balance economic concerns with institutional and political concerns. Political concerns may result in certain decisions being taken largely in the absence of evidence, driven by opinions, values, and political constraints. Institutional concerns relate to both ‘inhouse politics’ and ‘lags’ in policy-making, where resources can rarely be instantly transferred between uses. For instance, services often involve a precommitment to funding over certain time periods and involve contracted and skilled staff who may not be easily transferred to alternative uses. This slows the process of improving allocative efficiency. Fifth, there is a general lack of economic evidence regarding investments in the social determinants of health. To date, health economics has overwhelmingly concentrated on interventions within the health sector.

Furthermore, there are real difficulties in developing robust economic evidence. Many public health interventions are complicated in the sense that they are often multicomponent, making it difficult to identify active ingredients and to distinguish between a good intervention and poor implementation. Interventions are also complex in the sense that they can interact with local context (e.g., past and present interventions). In effect, context is an effect-modifier. Also, interventions may have the greatest impact over the long-term and even intergenerationally (e.g., urban regeneration). These common features can cause difficulties in establishing both causality (e.g., the opportunity for randomized trials is limited) and the generalizability of evidence, given that context can vary substantially between settings. The interaction of economic evidence with context provides an opportunity for interdisciplinary research in the future in order to improve both the generation and generalizability of evidence. Further, economics has a distinctive role to play in addressing the importance of context by analyzing how individual and organizational choices and behavior are likely to respond to changes in context-specific incentives and constraints.

Priority Setting As A Management Process

Priority setting is essentially a management process. This process needs to balance a wide range of concerns given that stakeholders often have competing objectives and diverse political and institutional constraints, and given the difficulties of generating robust evidence regarding likely policy outcomes. Owing to lack of evidence, the prioritization process is often fundamentally driven by value judgements. The priority setting process grows even more challenging when we consider the challenge of coordination between multiple policy sectors.

Priority Setting Tools: Framing The Decision Process

The priority setting process can often lack transparency and accountability. Policymakers themselves have expressed frustration regarding a lack of priority setting frameworks that they can use to guide decisions and enhance the credibility of resource allocation decisions. There is an opportunity for economists to help apply (and further develop) frameworks to steer decisionmakers through the process of priority setting, in addition to the generation of economic evidence.

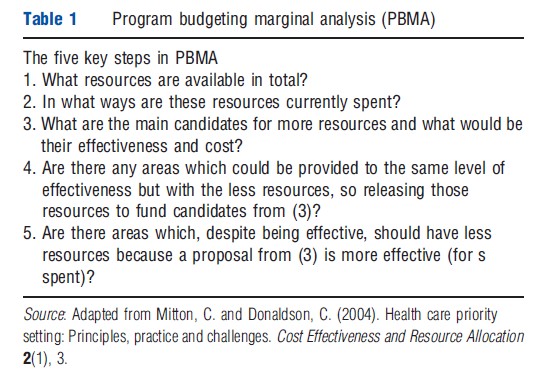

There are a variety of priority setting tools that have been developed over the past 40 years, often as part of an interdisciplinary process. So despite the frustrations of policymakers, the issue may be more of awareness and application of existing tools – from both policymakers and perhaps economists too. Two of the most common tools are program budgeting marginal analysis (PBMA) and multicriteria decision-making. The rationale for using such tools is similar: to make explicit and improve the transparency and accountability of the priority setting process. For illustration, PBMA can be discussed briefly.

PBMA has been used in mainly in the UK, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Further, it has mainly been applied within the health sector. However, PBMA could in principle be used in any priority setting process and to coordinate multiple sectors.

An advisory panel is normally established with key stakeholders to identify the aims and scope of the priority setting exercise. Thereafter, five simple steps are in the process that is aimed at ultimately identifying areas for investment and disinvestment. The first step is to articulate the resources available for consideration in a reallocation exercise. The second step is to map out how existing resources are currently spent. The third step is to then identify the main candidates for more resources that offer the greatest value for money. The fourth step is to look at ways by which existing resources can be spent more efficiently to free up resources for Step 3 (Table 1).

The fifth step is to then make comparisons across spending areas and transfer resources if the interventions identified in Step 3 offer greater value.

Ideally, economic evidence would exist and be comprehensive enough to inform steps 3–5. However, often this is not the case or there are additional political or institutional concerns. Therefore, a key issue is for stakeholders to develop explicit decision-making criteria. This may include things such as health gain, access, innovation, sustainability, staff retention/recruitment, and system integration. This is where multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) can be nested within a PBMA approach to help decisionmakers choose between options. MCDA essentially involves four main steps: identifying interventions; identifying evaluation criteria; measuring interventions against the criteria; and combining criteria scores using a weighting to produce an overall assessment of each intervention.

Applying Priority Setting Tools

In effect, there are three potential applications of priority setting tools. The first is to determine the initial funding to individual sectors. If health improvement and tackling health inequality are priorities, then funding nonhealth sector interventions may be a more productive approach than health sector interventions. Second, there is scope to use tools for the reallocation of funding within sectors to improve the efficiency of delivering outputs. This is particularly important when budgets may be under pressure due to a tighter fiscal environment. Third, these tools can in principle be used to coordinate sectors. This is where it becomes important for economic evidence to take an ‘integrated approach’ (combining different approaches to economic evaluation) and demonstrate to policymakers in different sectors the impacts of their decisions on one another, and the implications for health and overall social welfare. Through an explicit priority setting process, sectors can either compensate each other for the impacts of policies on one another, or ideally coordinate policies to create synergies and promote overall social value.

Conditions For Successful Priority Setting

For priority setting exercises to be successful certain conditions are required. Key amongst these is leadership. There needs to be willingness and commitment by leaders within organizations to the process and to ensure that resource reallocation can and does actually take place. Without leadership, the process can lack credibility. Priority setting exercises can also be time-consuming and involve senior staff in organizations. The opportunity to undergo these exercises may be limited to the start to the next budget cycle. Further, there needs to be a willingness to repeat the exercise, as experience has shown that organizations need a learning-by-doing period for the priority process to improve and develop credibility.

Overall, priority setting is inherently a messy process, involving economic, political, and institutional concerns. Priority setting tools can help willing participants to make explicit the decision process, articulate all issues and improve the rationality and accountability of resource allocation decisions. Tools such as PBMA can shape the decision process to accord with economic principles, to use the available economic evidence and make gains in technical and allocative efficiency.

Conclusions

This article has considered how economists can best engage with the ‘healthy public policy’ agenda, which is concerned with the social determinants of health where nonhealth sectors are considered to have significant impacts on population health and health inequalities. The practical challenge is how to generate and then translate economic evidence into decision-making in nonhealth policy sectors where, at present, health impacts are often considered as ‘byproducts’. Given intersectoral impacts are a common feature of most policies, the wider challenge is to facilitate the process of intersectoral coordination and alignment toward improvements in overall social welfare, where health is just one important element.

By taking an integrated societal approach, economists can produce a consistent body of evidence that is commensurate both with the most pressing objectives of funding sectors and with the first principles of economics. The aim is to help policymakers move beyond narrow sector-specific perspectives and take decisions to improve overall social welfare. An integrated approach can begin with a CCA and then convert outcomes into relevant cost effectiveness measures (both cost per unit of output and cost per generic unit of health gain), and then value all outcomes consistently within a CBA. In this sense, the seemingly different approaches of economic evaluation can be viewed as complimentary, where CCA and CEA are ‘nested’ within an overall CBA.

Priority setting tools can then be used to facilitate the translation of evidence into decision-making. Tools such as PBMA are consistent with a societal approach and can help frame the scope of the priority setting exercise, facilitate stakeholders coming together, and make explicit the decisionmaking criteria so that evidence can be used systematically.

Overall, economics has much to offer public health to help facilitate intersectoral alignment so that decisionmakers take account of wider social determinants of health. Equally, public health has much to offer health economics; providing an opportunity to rediscover the societal approach where the ultimate aim of economics is to allocate scarce resources for the improvement of overall social welfare, wherein health is just one important element.

References:

- Mitton, C. and Donaldson, C. (2004). Health care priority setting: Principles, practice and challenges. Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation 2(1), 3.

- Bernier, N. F. (2007). Breaking the deadlock: Public health policy coordination as the next step. Healthcare Policy 3(2), 117–127.

- Coast, J. (2004). Is economic evaluation in touch with society’s health values? British Medical Journal 329(7476), 1233–1236 (and the responses to this article).

- Cookson, R. and Claxton, K. (eds.) (2012). The humble economist: Tony Culyer on health, health care and social decision making. York: University of York and London: Office of Health Economics.

- Dahlgren, G. and Whitehead, M. (1991). Policies and strategies to promote social equity in health. London: Institute of Fiscal Studies. Available at: http:// ideas.repec.org/p/hhs/ifswps/2007_014.html (accessed 01.11.12).

- Donaldson, C. (2011). Credit crunch health care: How economics can save our publicly funded health services. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Dionne, F., Mitton, C., Smith, N. and Donaldson, C. (2009). Evaluation of the impact of program budgeting and marginal analysis in Vancouver Island Health Authority. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy 14(4), 234–242.

- Hauck, A., Smith, P. C. and Goddard, M. (2003). The economics of priority setting for health care: A literature review. Washington: World Bank; 2003. Available at: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/HEALTHNUTRITIONANDPOPULATION/ Resources/281627-1095698140167/Chapter3Final.pdf (accessed 01.11.12).

- Joffe, M. and Mindell, J. (2004). A tentative step towards healthy public policy. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 58(12), 966–968.

- Kelly, M. P., McDaid, D., Ludbrook, A. and Powell, J. (2005). Economic appraisal of public health interventions. Briefing paper; Health Development Agency (London: part of the UK’s National Institute of Clinical Excellence). Available at: http://www.cawt.com/Site/11/Documents/Publications/Population%20Health/ Economics%20of%20Health%20Improvement/Economic_appraisal_of_public_ health_interventions.pdf (accessed 01.11.12).

- Leischow, S. J., Best, A., Trochim, W. M., et al. (2008). Systems thinking to improve the public’s health. Americal Journal of Preventive Medicine 35(2 Suppl), S196–S203.

- Marsh, K., Dolan, P., Kempster, J. and Lugon, M. (2012). Prioritizing investments in public health: A multicriteria decision analysis. Public Health 1–7.

- McQueen, D., Wismar, M., Lin, B., Jones, C. M. and Davies, M. (eds.) (2012). Intersectoral governance for health in all policies. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe on behalf of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies.

- Mortimer, D. (2010). Reorienting programme budgeting and marginal analysis (PBMA) towards disinvestment. BMC Health Services Research 10, 288.

- Shiell, A., Hawe, P. and Gold, L. (2008). Complex interventions or complex systems? Implications for health economic evaluation. British Medical Journal 336(7656), 1281–1283.

- Sibbald, S. L., Singer, P. A., Upshur, R. and Martin, D. K. (2009). Priority setting: what constitutes success? A conceptual framework for successful priority setting. BMC Health Services Research 9, 43.

- Wanless, D. (2004) Securing good health for the whole population. UK: HM Treasury.