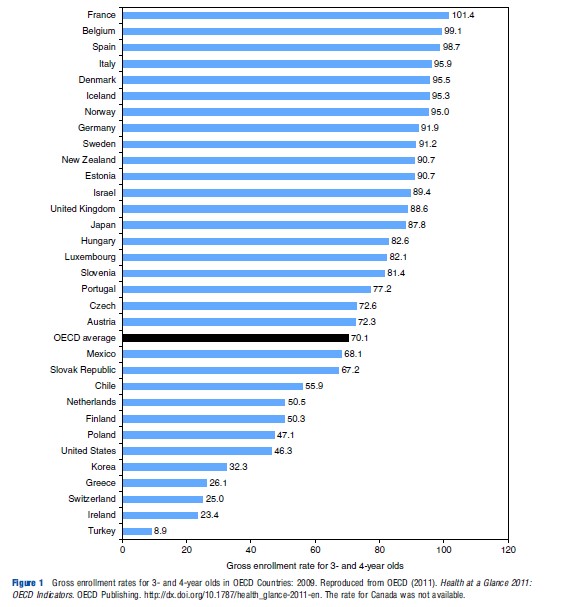

In recent years, it has become increasingly common for children to be enrolled in preschool education programs for one or more years before the traditional starting age for primary school. According to data from the World Bank, during 2010, 48.3% of preprimary-age children were enrolled in school, a rate that was just 34.1% a decade earlier. Although preprimary enrollment rates in high-income countries far exceed those of low-income ones (82.2% on average vs. 14.9% on average), enrollment rates have been rising since a decade in countries across the development spectrum. Preschool participation rates are not strictly related to the level of economic development, however. Even among high-income countries such as those in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), there is considerable variation in the share of 3and 4-year-olds enrolled in preschool programs (see Figure 1). Although the preschool enrollment rate during 2009 exceeded 90% in Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Iceland, Italy, Norway, Spain, and Sweden, it was not even half that rate in Greece, Ireland, Korea, Switzerland, Turkey, and the US.

The high and rising rates of preschool enrollment across most countries reflect a growing demand among parents for early learning opportunities before the age at which school traditionally begins, as well as enthusiasm on the part of governments across the globe for supporting such programs with public funds. Interest in early childhood investments have been bolstered by research in early childhood development, which has advanced toward a more in-depth understanding of the importance of the early years for lifelong health and development. Emerging evidence from neuroscience, molecular biology, genomics, psychology, and social sciences have converged to provide a new paradigm pointing to the role of both genes and the environment for shaping physical and mental health from the point of conception through to adulthood. Early adversity from nutritional deprivation to insufficient emotional support, or limited cognitive stimulation can trigger the human body’s stress management systems in ways that can be protective or harmful, depending on the available supports. These scientific findings serve as a foundation for the theoretical framework put forth by the Nobel Laureate of 2000 in Economics, James Heckman along with his colleagues, which views skill formation as a life-cycle process wherein abilities are both inherited and developed. In this framework, the development of human capital at one stage in life boosts skill attainment at later stages, and early investment improves the productivity of later investments, resulting in a high rate of return to early investment, as skill begets skill.

In the light of these trends and scientific foundations, the goal of this article is to highlight the specific research base that provides support for early education investments. In particular, two strands of research put together strengthen the support on the part of policymakers, practitioners, and parents for preschool education. First, a growing body of evaluation evidence has demonstrated that high-quality early learning programs can boost school readiness and provide long-term benefits in multiple domains. Second, benefit–cost calculations by economists have confirmed that effective programs can more than pay back their costs. Although there are some important caveats and knowledge gaps in each of these research areas, the case for preschool investments rests on a solid research foundation.

Throughout this discussion, it is important to bear in mind that preschool programs defined herein serve children 1 or 2 years before formal primary schooling begins, taking on various forms depending on the country, time period, source of funding, and provider (an even broader array of early childhood intervention models, not being considered here, begin as early as pregnancy and offer services to parents and children in home and center settings in the first 3 years of life, sometimes beyond). Preschool programs may focus on one or more developmental domains including language and cognitive development; behavioral, social, and emotional competencies; and mental and physical health including nutrition. Programs may be delivered in a group setting, such as a child care center or an elementary school; in some countries, home-based providers also offer formal early learning programs. Program intensity can vary, with offerings over 1 year or multiple years that range from part-day programs delivered during the academic year to full-time year-round programming. In addition to programs centered on the child, some programs also engage the child’s parents in the learning process through home visits, parenting classes, and other activities. Finally, programs may be fully or partially subsidized by the public sector, with parents or other private sources of support (e.g., employers or philanthropies) filling any gaps.

Evidence From Program Evaluations

For many, the findings from brain research and other developmental science is sufficient justification for providing children – particularly those with disadvantaged backgrounds – with various developmental supports, including formal early learning programs. Yet, preschool programs can take many forms, with considerations for features such as the number of children in a group setting, the ratio of adults to children, the education and training background of the caregivers or teachers, and the choice of an early learning curriculum. With uncertainty over what constitutes an effective program – one that will achieve the goal of supporting children’s developmental progress – a body of evaluation research has accumulated to assess the effectiveness of particular program models or specific program features.

The gold standard for evaluation evidence is an experimental design. If outcomes of children who are enrolled in a preschool program are compared with those of children not enrolled, the observed differences may arise from the program itself, or from other factors that influence parental choice regarding preschool enrollment as well as child development. This issue of selection bias is avoided with a well-designed experimental study. Random assignment to the treatment group (program participation) versus the control group (no participation) ensures that all other possible determinants of child outcomes are controlled for, so that any observed differences in outcomes between treatment and control children are the result of the intervention.

Of course, experimental studies may be unethical and impractical, or too costly to launch. In such cases, quasi-experimental methods that closely replicate experimental conditions may be feasible. For example, one common method used in the US to evaluate a number of state-funded preschool programs for 4-year olds is a regression discontinuity (RD) design. This approach exploits the strict age-cutoff used to determine when children can enroll in a state preschool program. Effectively, this method uses the accidental birth to compare a child whose birthday occurs just before the enrollment cutoff (and is therefore able to enroll and experience the preschool treatment) to a child who just misses the birthdate cutoff (and therefore does not experience the program being unable to enroll until next year).

Rigorous Evidence From The USA And Other Countries

In the US, rigorous evaluations of voluntary preschool programs serving 3 and 4-year olds have been conducted for small-scale demonstration programs implemented during the 1960s and targeted to very disadvantaged children, such as the High/Scope Perry Preschool Program and the Early Training Project, and for programs implemented on a large scale and evaluated for more recent cohorts of low-income children such as the Chicago Child–Parent Centers (CPC) program by the Chicago public school system and the federally funded Head Start program. More recently, the RD quasi-experimental method has been used to assess the impact of several state-funded preschool programs targeting children from low-income families as well as Oklahoma’s preschool program, which is one of the few programs for 4-year-old children in the US.

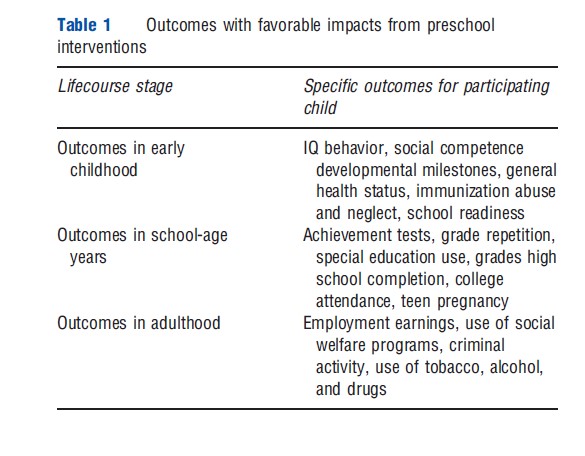

Taken together, the evidence from the US evaluation research – synthesized in studies by Barnett, Burchinal, Gormley, Pianta, Shonkoff, and others – has demonstrated that well-designed preschool programs can improve child developmental outcomes on both short and long-term bases. Based on an assessment of the literature from the US by Karoly and colleagues, Table 1 lists the specific outcomes that have been significantly affected by at least one rigorous (i.e., experimental or well-designed quasi-experimental) evaluation of a preschool program serving children for 1 or 2 years before kindergarten entry. The bulk of the evidence base is in the first tier of Table 1, as all preschool evaluations measure some early childhood outcomes. Most evaluations, for example, find significant favorable effects on one or more developmental measures that are assessed during the program or soon after. Such outcomes in early childhood include measures of general intelligence or intelligence quotient (IQ), assessments of school readiness such as specific prereading and premath skills, as well as gains in socioemotional or behavioral competencies. Meta-analyses across multiple studies being conducted in the US tend to show larger average treatment effect sizes for impacts on cognitive outcomes – in the range of 0.2–0.3, when compared with impacts on socioemotional or behavioral outcomes. Larger impact estimates have been found for specific studies and these indicate that intentional design can boost program impacts beyond those measured for typical programs. The magnitudes found for the most effective programs are large enough to close half or more of the achievement gap between disadvantaged children and their more advantaged peers.

A more limited evidence base supports the second and third tiers in Table 1, with confirmation of the benefits from preschool programs continuing into the school-age years and persisting beyond. Studies with follow-up intervals, pertaining to elementary school and later grades – such as the Perry Preschool and Chicago CPC evaluations – demonstrate higher achievement scores, reduced rates of grade repetition and special education use, and higher high school graduation rates. These two studies, with continued follow-up into adulthood (age 40 for Perry Preschool and age 26 for Chicago CPC), also find favorable impacts in other domains like employment and earnings, social welfare program use, criminal activity, and health behaviors. Many of these same impacts are found for other targeted intensive early intervention programs such as the Carolina Abecedarian Project, which provides fulltime year-round center-based educational programming till kindergarten entry, starting just few weeks after birth.

In many European countries, where preschool participation rates are almost universal, fewer experimental or quasi-experimental studies have been conducted. Longitudinal studies such as the 1958 British Cohort Study and the 1997 Effective Provision of Preschool Education Project in England provide observational evidence of the favorable effects of preschool participation on child development both in the short and long runs. In developing countries such as Argentina, Jamaica, Mauritius, the Philippines, Turkey, Uganda, Uruguay, and Vietnam, a number of experimental and quasi-experimental evaluations of preschool programs have been implemented, often in combination with other services pertaining to child health and nutrition. Recent syntheses or formal meta-analyses of the evaluations of non-US programs, conducted by Nores and Barnett and by Vegas and Santibanez, among others, document that the favorable impacts found in US studies across multiple developmental domains are replicated throughout the range of low-income to high-income countries. At the same time, there is also considerable variation in the magnitude of the impacts across program models. Such differences may be attributable to program design or the populations served.

Limitations Of The Knowledge Base

Although the cumulative evidence from rigorous evaluation studies is very compelling, it is important to recognize the limitations of the research to date. First, much of the evidence of preschool program benefits have stemmed from studies of programs targeting disadvantaged children. This is especially true for the kind of research in the US where both small-scale demonstration programs and large-scale models like Chicago CPC or Head Start serve children in families with limited resources or other disadvantages. One exception for the US is the evaluation of Oklahoma’s universal preschool program, which has demonstrated significant favorable impacts across income and race-ethnic groups, although the evidence suggests that the benefits from preschool participation are greater for the more disadvantaged children. Nevertheless, even children from families with income above poverty are likely to face various stressors that can comprise their healthy development and readiness for school. The Oklahoma results suggest that the benefits from participation in a high-quality preschool program may be broadly shared.

Second, evaluations of specific preschool programs demonstrate proof of the principle that high-quality early learning programs can improve child developmental outcomes on both short- and long-term bases. However, such evidence does not confirm that every program will necessarily have favorable impacts or effects that are equal in magnitude to those found in specific evaluations. In most cases, existing evaluations quantify the impact of specific combinations of preschool inputs as a bundle: group size, staff–child ratio, curriculum, teacher education and training, teacher–child interactions, total hours spent in the program, and so on. The evaluation can neither tease apart the effect of specific inputs nor identify the impacts that would result with some different combination of factors. Essentially, the research to date largely treats each evaluated preschool program as a ‘black box’ sans the ability to identify which program factors account for the measured impacts. Implementing programs with different combinations of inputs or with different levels of intensity may well produce different impacts, but how much different remains largely unknown. Given these limitations, ongoing research is seeking to understand issues such as whether there are minimum levels of quality required for programs to be effective and how program impacts vary with program dosage (e.g., annual hours in the program).

Third, as participation in some form of early care and education has become more common over time, especially in high-income countries, it has become challenging to measure the impact of preschool program participation against a true ‘no program’ control group. For example, in the national Head Start experimental evaluation conducted during the early 2000s in the US by Westat and others for the US Department of Health and Human Services, 48% of the 4-year olds in the control group participated in some form of center-based program and 13% attended some other Head Start program than the one they were randomized out of. Thus, the experimental evaluation had measured the effect of participation in Head Start against the status quo where nearly half of 4-yearold children living in poverty were already in some form of early education program. In contrast, when programs like Perry Preschool were evaluated in the 1960s, US children in the control group did not have access to other early learning programs, and were thus in a control condition of parental care only. In other countries with very high preschool enrollment rates, the opportunities for measuring program impacts against a ‘no program’ control group are very limited. For this reason, ongoing research is centered on assessing the impact on child developmental outcomes from different preschool program designs so as to identify which program models are most effective, rather than trying to assess whether programs have an impact when compared with the alternative of no program participation.

Economic Case For Preschool Investments

In an era of result-based accountability, there has been a growing interest in the US and other countries in demonstrating that the investments in public sector programs generate a favorable economic return to the public sector or at least to society as a whole. This has prompted increased application of benefit–cost analysis (BCA) methods to social policies, including early childhood programs.

The BCA methodology requires (1) a comprehensive measure of program costs relative to the baseline without the program; (2) evidence of the causal impact of the program relative to the same baseline; and (3) the ability to value all the program impacts in a common monetary value, often called ‘shadow prices.’ The method then compares the present value of the stream of program costs with that of the stream of lifetime program impacts (whether favorable or unfavorable) to determine whether net benefits are greater than zero or alternatively the ratio of benefits to costs is greater than one. This accounting of benefits and costs can be conducted from the perspective of different stakeholders. Most common is to calculate the economic returns for the public sector – accounting for the costs or benefits to taxpayers of a given intervention. The most comprehensive perspective is for the society as a whole, accounting for benefits and costs that accrue to the public sector as well as private benefits and costs that accrue to program participants and non-participants.

The Application Of Benefit–Cost Analysis To Preschool Programs

For both preschool programs and other early childhood interventions, one of the challenges in applying BCA is that many of the outcomes affected by these programs are neither easily valued in dollars nor in some other monetary unit. The early childhood outcomes listed in the first tier in Table 1 including those related to child health are ones where ready shadow prices do not exist for the most part. Consequently, BCA has not been employed for many preschool interventions. When the tool is used, the lack of ready shadow prices means that the economic returns tend to be understated because benefits are undercounted relative to costs.

Given the challenge of placing an economic value on early childhood outcomes, the application of BCA to preschool programs has mostly been limited to those programs with long-term follow-up into the school-age years and beyond, because more of such outcomes can be valued. For example, if a preschool program leads to reductions in the use of special education services, then that represents a savings to the public sector because children will be enrolled in regular education classes instead of the more costly special education programs. Likewise, if a preschool program boosts high school graduation rates, then that can lead to an increase in lifetime earnings for the children when they reach adulthood, and those higher earnings can generate more tax revenue to the government. Achieving higher educational attainment is also likely to reduce the use of social welfare programs and lower the incidence of crime. Therefore, benefits in these areas may be projected based on any measured educational gains; or these outcomes may be directly observed as they have been in the long-term follow-ups of the Perry Preschool and Chicago CPC evaluations.

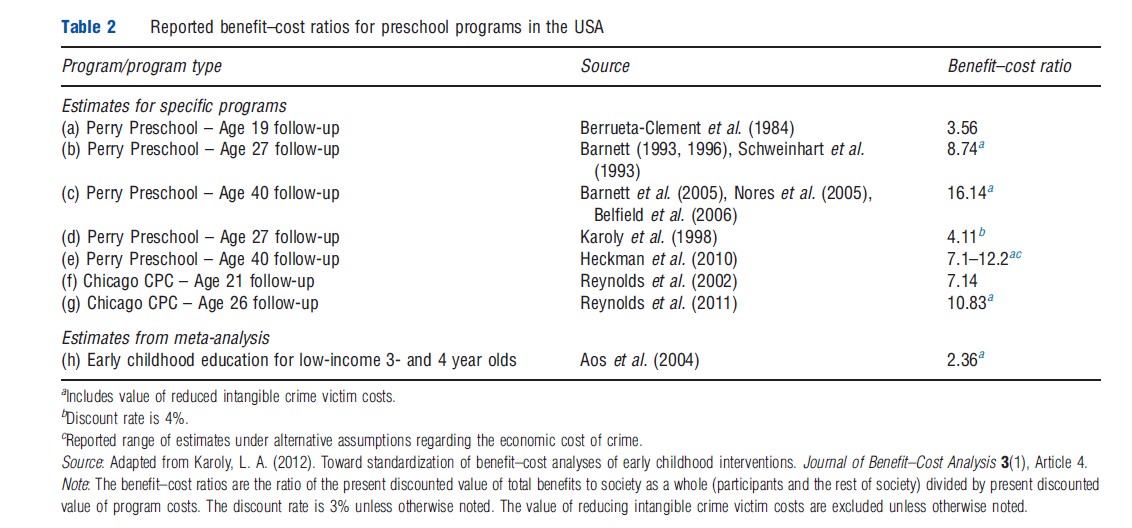

As two of the preschool programs with long-term follow-up, the Perry Preschool and Chicago CPC programs have been the focus of a series of BCAs. As shown in Table 2, Perry Preschool has been the subject of at least five different BCAs, three are conducted by the High/Scope evaluation team using updated information at each adult follow-up stage (studies (a), (b), and (c), using follow-up data at ages 19, 27, and 40, respectively) and two are conducted by other research teams using somewhat different methods (studies (d) and (e) based on follow-up data at ages 27 and 40, respectively). The Chicago CPC program has been the subject of two BCAs by the evaluation team using follow-up data at ages 21 and 26 (studies (f) and (g), respectively). Table 2 also shows the benefit–cost ratio for a study by the Washington State Institute of Public Policy, which is based on a meta-analysis of early childhood education programs serving 3 and 4-year-old children in low-income families (study (h)). Thus, rather than a BCA for a specific preschool program, this analysis represents the likely return for high-quality preschool programs on average when implemented at scale.

These results demonstrate several patterns. First, in all cases, the analyses show that the programs generate positive economic benefits with benefit–cost ratios ranging from $2.36–1 to $16.14–1. As Heckman notes, the findings for these programs and other early childhood interventions demonstrate that early childhood investments offer a rare policy option that can promote both economic efficiency, as well as fairness and social justice. Second, as more follow-up data becomes available, the calculated economic returns tend to increase. This is because, the methods of both the Perry Preschool and CPC BCAs to project future benefits are typically too conservative when compared with the actual experiences from later follow-ups. Third, methodological choices matter in the calculated returns. For example, unlike the evaluation teams, the independent estimates for the Perry Preschool program (studies (d) and (e)) made different choices like excluding the value of intangible crime victim costs or using different values for the cost of crime. As the available estimates of crime costs vary widely, these choices can have a considerable impact on the estimated returns. Fourth, the estimates of returns for specific programs will not necessarily generalize those for more generic preschool programs. The lowest benefit–cost ratio in Table 2 is for the more generalized targeted preschool program where the estimated program impacts are assumed to be attenuated because of program scale-up. Thus, this estimate may be closer to what the typical ‘real world’ program would generate.

Limits On The Generalizability Of Existing Economic Analyses

The issue of the generalizability of the findings in Table 2 for either the small-scale Perry Preschool program or the large-scale Chicago CPC program is an important one. Both programs have been designed to serve particularly disadvantaged groups of children, and the estimated program impacts and the associated benefit–cost ratios thereof may not be replicated in other programs or for other populations of children. Programs that are less effective due to lower quality would not be expected to generate the same economic return. Likewise, programs serving more advantaged groups of children would not necessarily have impacts across the same range of outcomes or of the same magnitude. To the extent that impacts are attenuated when quality declines or the population served varies, the economic returns would be lowered accordingly. However, the attenuation of program impacts when programs serve a broader base of children does not necessarily mean that the economic returns will no longer be positive. For example, several studies have estimated the returns to universal preschool programs while assuming that the favorable impacts are concentrated among the most disadvantaged children. Even so, the total economic benefits to society as a whole can remain positive, so long as the returns for the disadvantaged groups are sufficiently large.

The economic returns to preschool programs implemented in other countries is also an issue that remains largely unexplored, and the magnitudes of the economic returns demonstrated for programs in the US may not be relevant for other developed or developing countries. Economic returns may be higher or lower depending on how the magnitude of program impacts can vary in other countries and also depending on the variation in the economic values attached to the realized program impacts. For example, the high economic returns to Perry Preschool stem, in part, from the high cost of juvenile and adult crime in the US, costs that are likely to be lower in most other countries in the world. For this reason, rigorous program evaluations in all countries need to be accompanied by careful estimates of program costs and benefits. In addition, in the absence of long-term follow-up data from interventions in both high and low-income countries, there is a need to develop estimates of the economic value associated with changes in child health and development in the early years.

References:

- Aos, S., Lieb, R., Mayfield, J., Miller, M. and Pennucci, A. (2004). Benefits and costs of prevention and early intervention programs for youth. Olympia: Washington State Institute for Public Policy.

- Barnett, W. S. (1993). Benefit-cost analysis of preschool education: Findings from a 25-year follow-up. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 63(4), 500–508.

- Barnett, W. S. (1996). Lives in the balance: Age-27 Benefit-cost analysis of the high/scope perry preschool program. Monographs of the High/Scope Educational Research Foundation, 11. Ypsilanti, MI: High/Scope Press.

- Barnett, W. S., Belfield, C. R. and Nores, M. (2005). Lifetime cost-benefit analysis. In Schweinhart, L. J., Montie, J., Xiang, Z., et al. (eds.) Lifetime effects: The high/scope perry preschool study through age 40, pp. 130–157. Monographs of the High/Scope Educational Research Foundation, 14. Ypsilanti, MI: High/Scope Press.

- Belfield, C. R., Nores, M., Barnett, W. S. and Schweinhart, L. (2006). The high/scope perry preschool program: Cost-benefit analysis using data from the age- 40 follow-up. Journal of Human Resources 41(1), 162–190.

- Berrueta-Clement, J. R., Schweinhart, L. J., Barnett, W. S., Epstein, A. S. and Weikart, D. P. (1984). Changed lives: The effects of the perry preschool program on youths through age 19. Monographs of the High/Scope Educational Research Foundation, No. 8. Ypsilanti, MI: High/Scope Press.

- Heckman, J. J., Moon, S. H., Pinto, R., Savelyev, P. A. and Yavitz, A. (2010). The rate of return to the high scope perry preschool program. Journal of Public Economics 94(1–2), 114–128.

- Karoly, L. A., Greenwood, P. W., Everingham, S. S., et al. (1998). Investing in our children: What we know and don’t know about the costs and benefits of early childhood interventions. Santa Monica, CA: The RAND Corporation. MR-898.

- Nores, M., Belfield, C. R., Barnett, W. S. and Schweinhart, L. (2005). Updating the economic impacts of the high/scope perry preschool program. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 27(3), 245–261.

- Reynolds, A. J., Temple, J. A., Robertson, D. L. and Mann, E. A. (2002). Age 21 cost-benefit analysis of the title I Chicago child-parent centers. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 24(4), 267–303.

- Reynolds, A. J., Temple, J. A., White, B. A., Ou, S.-R. and Robertson, D. L. (2011). Age-26 cost-benefit analysis of the child-parent center early education program. Child Development 82(1), 379–404.

- Schweinhart, L. J., Barnes, H. V. and Weikart, D. P. (1993). Significant benefits: The high/scope perry preschool study through age 27. Monographs of the High/ Scope Educational Research Foundation, 10. Ypsilanti, MI: High/Scope Press.

- Burchinal, M., Vandergrift, N., Pianta, R. and Mashburn, A. (2009). Threshold analysis of association between child care quality and child outcomes for lowincome children in pre-kindergarten programs. Early Childhood Research Quarterly 25, 166–176.

- Camilli, G., Vargas, S., Ryan, S. and Barnett, W. S. (2010). Meta-analysis of the effects of early education interventions on cognitive and social development. Teachers College Record 112, 579–620.

- Cunha, F., Heckman, J. J., Lochner, L. J. and Masterov, D. V. (2006). Interpreting the evidence on life cycle skill formation. In Hanushek, E. A. and Welch, F. (eds.) Handbook of the economics of education. pp. 697–812. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

- Gormley, W. T. (2007). Early childhood care and education: Lessons and puzzles. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 26, 633–671.

- Karoly, L. A. and Bigelow, J. H. (2005). The economics of investing in universal preschool education in California. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

- Karoly, L. A., Kilburn, M. R. and Cannon, J. S. (2005). Early childhood interventions: Proven results, future promise. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

- Knudsen, E. I., Heckman, J. J., Cameron, J. L. and Shonkoff, J. P. (2006). Economic, neurobiological, and behavioral perspectives on building America’s future workforce. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103, 10155–10162.

- National Scientific Council on the Developing Child and the National Forum on Early Childhood Policy and Programs (2010). The foundations of lifelong health are built in early childhood. Cambridge, MA: Center on the Developing Child, Harvard University.

- Nores, M. and Barnett, W. S. (2010). Benefits of early childhood interventions across the world: (Under) Investing in the very young. Economics of Education Review 29, 271–282.

- Pianta, R. C., Barnett, W. S., Burchinal, M. and Thornburg, K. R. (2009). The effects of preschool education: What we know – how public policy is or is not aligned with the evidence base, and what we need to know. Psychological Science in the Public Interest 10, 49–88.

- Shonkoff, J. P. and Phillips, D. A. (eds.) (2000). From neurons to neighborhoods: The science of early child development. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

- Vegas, E. and Santibanez, L. (2009). The promise of early childhood development in Latin America and the Caribbean. Issues and policy options. New York, NY: The World Bank and Palgrave MacMillan.