Many public health interventions are extremely good value for money. Advice from doctors to give up smoking, vaccinations against communicable diseases, or improved access to clean water in low-income countries are often relatively low cost interventions that produce substantial health gains. Where evidence on cost-effectiveness is available, many preventive and public health interventions fare very well when compared with conventional healthcare interventions. So why are not more public funds invested in public health? And why in some situations has it been so difficult to implement common-sense public health interventions such as sewage treatment, vaccinations, or taxes on cigarettes?

The articles on economics of public health, infectious disease externalities, health behavior externalities and public health priority setting discuss the welfare economic theories of public goods and externalities that are relevant to most public health interventions and that support the case on theoretical grounds for their public provision. But these theories also describe the unique characteristics of public health interventions that inevitably put them at a disadvantage when compared with other investments, in particular investments in health care. Although health care is directly consumed by the individual patient and can offer large, immediate, and certain health benefits, public health actions to mitigate externalities typically offer only small, delayed, and uncertain benefits to particular individuals – even though this may add up to large and certain benefits at the population level. In summary, as Glied (2008) put it: ‘‘Public health, economic theory says, is most useful and beneficial when nobody can observe cash savings because of the actions of public health; when public health activities don’t even try to reduce taxes; when the potential benefits of public health actions are unclear; and when the potential beneficiaries of public health activities aren’t even born yet!’’ These are the sort of reasons why robust evidence of causal effects from controlled trials and natural experiments is often not available, and so it is difficult to demonstrate convincingly the societal value of public health interventions using conventional economic evaluation tools.

The article on economic evaluation of public health interventions discusses problems affecting the assessment of the cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) of public health interventions, and how they could be overcome. But can the authors necessarily conclude that it is poor evidence on the value of public health interventions that made policy makers shy away from making these investments? Did the scientific community fail to produce the kind of evidence that would convince policy makers to do the right thing? Or are there more fundamental structural impediments to securing acceptance of the value of such investments?

The authors argue in this article that it is the realities of the political decision-making process that militate against political backing for public health investments, rather than the methodological shortcomings of CEA. Although economic evaluation offers a powerful rational approach to setting priorities, there may be alternative perspectives from which it is rational for decision makers to disregard the recommendations. The authors use three economic models of public choice – the interest group, majority voting, and bureaucratic decision-making models – to explain why it may be rational even for benevolent social welfare maximizing decision makers to diverge from the traditional economic evaluation approach and take into account public choice theory in order to assess the various political constraints on the decision options available to them, and the likely unintended consequences of alternative policies due to the predicted behavioral responses of key stakeholder groups, and possibly even responses of their social decision-making colleagues in other branches of government who unlike themselves may not behave like benevolent social welfare maximizer. The models help us move from the normative approach to priority setting, based on what should be done to maximize some concept of social welfare, into the realm of positive approaches that attempt to understand what happens in practice.

Models of public choice assume that the same behavioral model that can be used to explain decision making in ordinary markets can also be applied to decision making in the public sector. Public policy makers are not necessarily benevolent maximizers of social welfare, but may be motivated by their own self-interest. Firms seek to maximize profits, consumers seek to maximize utility, and policy makers seek to maximize political support or their own personal gain. The models further assume that, although policy errors are certainly possible, it is more informative to assume that the intended effects of a policy can be deduced from the observed effects, especially when such policies persist over time. In doing so, the authors do not of course argue that such behavior is desirable, or that it happens in all circumstances. Of course individuals have various motivations and the authors acknowledge that many decision makers will act with predominantly altruistic and welfare maximizing considerations in mind. The aim is merely to offer a framework for explaining apparently perverse actions on the part of decision makers.

Interest Groups

The interest group model is a powerful way of explaining why policy making diverges from the recommendations of cost-effectiveness analysis. It demonstrates that some groups of the population are more successful in promoting their interests than other groups and seeks to explain the impact this has on priority setting, resource allocation, redistribution of wealth, and even the survival of governments. The ‘capture’ theory describes interest groups as ‘capturing’ the regulatory power of the state to achieve a redistribution of wealth between different groups of the population in the form of transfers that may be cash or favors (Stigler, 1971). Generally, small groups with a clearly defined common objective – for example, the pharmaceutical industry – have lower costs in organizing themselves, securing cohesion, and effectively lobbying decision makers to their advantage, at the expense of the larger population whose interests may be more diffuse and experience higher costs of organizing. Some interest groups have privileged access to information that gives them a comparative advantage. The authors shall discuss examples where powerful minority groups with the interest, means, and opportunity to organize themselves have influenced political decisions to their advantage.

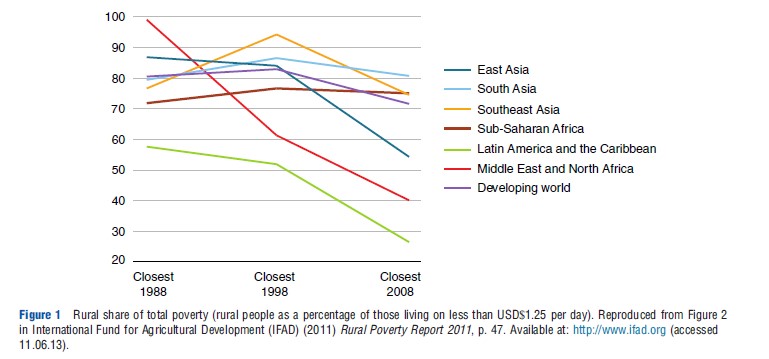

In low-income countries (LICs), the interest group model can explain why expenditures have often focused on healthcare services for richer areas or social groups at the expense of preventive and public health services for the poor, even where the latter offers greater cost-effectiveness. Poorer groups and populations based in rural areas may be less informed, less literate, and have an underdeveloped infrastructure for the dissemination of information compared to wealthier groups or those based in the urban areas where access to information resources is less limited. Groups in formal employment and with greater wealth also tend to be concentrated in urban areas, in particular in low-income Asian countries, see Figure 1.

Taxpayers represent an important interest group, especially in LICs with high levels of informal employment and a tax base that is highly dependent on a small minority of wealthy citizens. These citizens tend not to suffer to nearly the same extent from the communicable diseases and chronic conditions suffered by poorer citizens. In a democratic system, as the proportion of poor in the overall electorate is relatively large, most tax-financed healthcare expenditure would be devoted to illnesses of the poor in order to secure support of the majority of voters. However, such a policy choice would imply very large financial transfers, through the tax regime, from the rich to the poor. In short, the rich may have to make big tax contributions to public interventions that do not benefit them greatly. This may lead to resistance among the rich, tax evasion, increased collection costs, or even emigration.

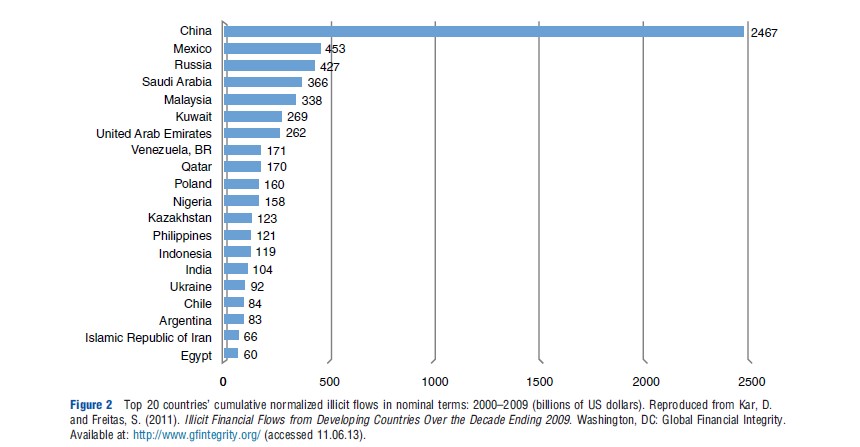

An extreme form of tax evasion is illicit export of capital, especially prevalent when systems of governance are weak. It is estimated that the world’s poorest countries lose USD$900 bn each year through illicit flows of capital. Figure 2 shows the top 20 developing country exporters of illicit capital in declining order of average annual outflows, with China being the top exporter by far. Despite these high levels of tax evasion in some developing countries, however, economic theory of tax compliance predicts that global tax evasion should be much greater than it actually is, given the low extent of deterrence in most countries – conceptualized as the product of the probability of being detected and the size of the fine imposed. Empirical studies allude to an effect known as ‘fiscal exchange’: the more governments provide public services according to the preference of taxpayers in exchange for a reasonable tax price, the more taxpayers comply with the tax laws. In the mid-nineteenth century Switzerland, a voluntary school tax in the canton of Glarus provided sufficient revenue to finance education services, whereas a voluntary welfare tax to redistribute income in the canton of Appenzell i. Rh. had to be quickly turned into coercive taxation. This concept of ‘fiscal exchange’ has important implications for healthcare priority setting. To limit tax resistance of this kind among the rich, the government may feel constrained to include some provision for the healthcare needs of the rich in the essential package of care in order to retain the viability of the tax base, even when the associated treatments do not qualify for inclusion on strict cost-effectiveness criteria.

Even in well-functioning democracies, powerful interest groups affect resource allocation decisions. Patient associations have successfully lobbied governments to fund drugs publicly, even if there is doubt about their cost-effectiveness, or even clinical efficacy and safety, for example, the breast cancer drug Herceptin in the English National Health Survey (NHS). Patients with long-term chronic illnesses such as HIV/AIDS have a clear advantage in organizing themselves over the recipients of public health interventions. As public choice theory predicts, illnesses with comparably low prevalence are at an advantage, at least partly due to the fact that costs of organizing are lower. The preventive nature of many public health interventions implies that there is no clearly defined patient group that is lobbying in their favor, and public health has to rely on individuals or groups with altruistic motivation for support. Further, governments often prioritize sensitive political issues concerning highly visible aspects of healthcare services, at the expense of investments in public health. For example, some countries place a high priority on tackling waiting times for elective surgery, which affect a relatively small group of patients. This preoccupation could be interpreted as a response by politicians to the more media-friendly interests of waiting patients when compared with interventions aimed at the whole population, or large and difficult to delineate subgroups of individuals at risk, such as preventive screening or healthy lifestyle campaigns.

Providers of health services – the healthcare professions – form a crucial interest group in many countries, and governments are often wary of alienating doctors who are in a strong position to mobilize opposition to chosen priorities. For example, in the USA, health professionals and their associations are major lobbyists. In 2012, they have together spent more than USD$40 M to influence directly or indirectly decisions made by Congress and federal agencies, an amount that is nearly 6 times more than the tobacco industry. Although providers would certainly not want to be seen to actively work against the interest of patients, it is unlikely that investments in public health feature prominently among their priorities, especially if such investments are made at the expense of traditional healthcare interventions or even reduce demand for their services.

Doctors may have credible threats that can undermine the implementation of policy shifts, ranging from overt threats such as quitting the workforce to subtle noncooperation and adherence to traditional patterns of care. For example, it has been argued that the retreat from traditional models of managed care in the USA has in large part been due to pressure from physician and consumer groups in a backlash against government and insurers’ attempts to cut costs through limiting access and rationing care. In some LICs, doctors may have a preference for high-technology medicine and be alienated by policy changes that seek to develop public health interventions and cost-effective care in community settings. Such alienation may have profoundly important consequences, for example, in the form of shifting employment from the public to the private sector or workforce emigration. Although migration is of course due to a multitude of reasons, it is noteworthy that in some LICs more than 50% of highly trained health workers leave for job opportunities in higher income countries.

The pharmaceutical industry is another powerful interest group that may favor healthcare interventions and drug treatment over public health investments. For example, The Council of the Europe Assembly quite openly voiced the suspicion that the pharmaceutical industry has influenced the World Health Organization’s response to the H1N1 flu pandemic. The Council accused WHO of exaggerating the seriousness of the epidemic, which resulted in large amounts of public funds being spent on vaccines and antivirals that were never needed. But the interests of the pharmaceutical industry are not always in conflict with public health or preventive policies. Modern antiretroviral treatment (ART) may prevent secondary HIV infections because HIV patients receiving ART may have a significantly reduced risk of passing on the virus to sexual partner (treatment as prevention), and ART given to healthy persons may reduce their risk of acquiring the virus (preexposure prophylaxis). Using ARTs as prevention would open up a vast new market for pharmaceutical companies, potentially comprising all HIV negative individuals at risk of infections.

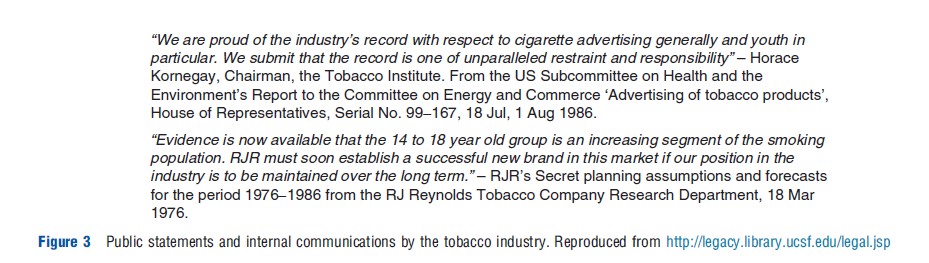

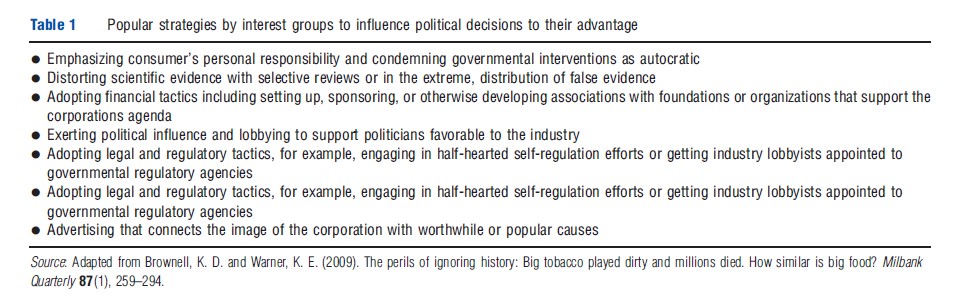

Other commercial companies that are driven by economic interests have formed powerful interest groups. Table 1 summarizes the – strikingly similar – strategies adopted by the tobacco and food-producing industries, and historically water companies, to influence public health decision making to their advantage. Many of the strategies the tobacco industry adopted to frustrate public health actions came to light only when an extensive library of internal tobacco industry documents was released publicly as a result of the 1998 settlement agreement. For decades before, the tobacco industry successfully preempted efforts to limit advertising and sale of cigarettes, by publicly disputing evidence that smoking cigarettes damages health, for example, with the infamous ‘A Frank Statement to Cigarette Smokers’, halfhearted self-regulation such as the Cigarette Advertiser Code, and public messages and advertising that emphasized individual responsibility to deflect blame from the industry. Public statements stood in stark contrast to internal communications (Figure 3).

Some public health experts now fear that history will repeat itself by comparing the tobacco industries’ strategies with current efforts by the food-producing industry to deny the contribution of their products, in particular soft drinks and highly processed snack food, to the obesity epidemic (Brownell and Warner, 2009). They accuse the food industry of following distraction strategies, for example, playing up the importance of physical activity over nutrition, publishing biased reviews of scientific studies, or playing up a relatively harmless health impact (such as tooth decay) to divert attention from the serious one (such as obesity).

The food industry has made highly visible pledges to curtail children’s food marketing, sell fewer unhealthy products in schools, and label foods in responsible ways, but has been criticized for their efforts (Sharma et al., 2010). For example, the School Beverage Guidelines developed by various charitable foundations in a partnership with the soft drink industry have been found to be implemented with far less restrictions in high schools, where much of the sugared-beverage intake occurs, than in elementary schools where little intake occurs.

It is telling that while contributions to federal candidates and political committees from the tobacco industry fell drastically from USD$10.6 M in 1996 when legal battles were at their peak to USD$3.2 M in 2010; over the same period, contributions from the food processing and food retail industry have tripled from USD$10 M to just under USD$30.5 M in 2010. This is possibly attributable to increased congressional action on issues that affect the industry such as food safety, labeling regulations, soft drink taxes, and other antiobesity initiatives.

There are, of course, differences between food and tobacco as substances. Unlike smoking, eating is necessary to maintain health and life. The associated public health messages are therefore more subtle, seeking to change the types and amounts of food eaten rather than promote abstinence. There is overwhelming evidence that smoking is addictive and damaging to health, whereas research on the addictive properties of food and its impact on human health is only now maturing. Smoking imposes harmful externalities on others through passive smoking, whereas in principle eating an unhealthy diet only harms the eater. The fight against tobacco coalesced around a single product made by a few companies, whereas the food industry is far more complex because it is fragmented, involving an immense array of products made by thousands of companies worldwide.

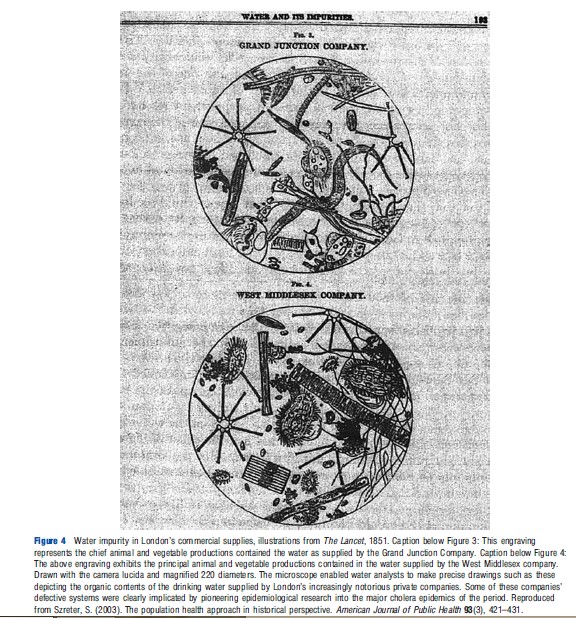

There are also historic examples of how commercial interests have shaped priority setting in public health. In fact, the public health movement that developed during the industrial revolution in the nineteenth century did so, at least partly, as a reaction to the commercial interests of private water companies. The water companies used their influence to dispute emerging evidence that the poor water quality they provided was responsible for the cholera epidemics and other illnesses that led to the appalling drop in life expectancy in English cities during the industrial revolution, using similar tactics to the tobacco industry 150 years later (Szreter, 2003). The development of germ theory and arrival of microscopic water analysis gave the public health movement the scientific backing to lobby for the construction of publicly funded and maintained sanitary infrastructure (see Figure 4).

Employers form an interest group that has traditionally supported public health interventions if they improve and preserve the productivity of their workforce. Historically, investments in public health in low-income countries were driven by the economic interests of colonial countries, and the need to guarantee the health of the workforce seconded to work there. For example, in Britain, in the 1890s, the Colonial Secretary Chamberlain was aware that the poor health of the native workers and the officials sent to serve in the Colonies was a threat to Britain’s growing empire. Mortality among officials in some parts of the world, particularly the Gold Coast of West Africa, was soaring and to compensate, salaries were sometimes 100% higher than those of colleagues elsewhere. The economic significance of the control of tropical disease led to establishment of institutions and schools of tropical medicine, such as the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (UK) and the Pasteur Institute (France). Nowadays, some mining companies are providing free Anti-retroviral therapy to their HIV positive employees, for example, Anglo-American. As HIV/AIDS predominantly affects working age adults, companies are possibly motivated by a combination of humanitarian interests and the commercial interest to preserve the human capital established in their workforce.

Even organizations seeking purely ‘technocratic’ solutions to priority setting by providing scientific evidence on the cost-effectiveness of interventions (e.g., health technology assessment agencies) may be influenced by interest groups in the selection of interventions chosen for assessment. Seeking public involvement in such activities risks capture by interest groups but can be seen as an attempt to increase political support for decisions. The National Institute for Clinical Excellence in England and Wales has formalized public involvement in technology appraisal and developing interventional procedure guidance, but not without criticism.

Voting Models

Many public health interventions are targeted at conditions that predominately affect disadvantaged groups of the population. Indeed, some even have the primary objective of reducing inequalities in health. This in itself may imply a need to depart from pure cost-effectiveness criteria, which imply an objective of maximizing aggregate health outcomes. The median voter model may explain why such public health interventions often receive less political backing than others that benefit a wider spectrum of the population, or why investments into healthcare are favored over investments in public health. The model focuses on the politician as a maximizer of votes (Hotelling, 1929; Anderson, 1999). The ‘median voter’ theorem shows that in a representative democracy, political parties tend to move toward the political position of the median voter in order to secure election.

The median voter model highlights the importance to the government of obtaining the support of crucial electoral constituencies. In public health, this may explain why policy makers seek to direct resources toward key population groups at the expense of others, notwithstanding the apparently reasonable claims of the latter on resources from an efficiency or equity perspective. For example, median voters are likely to perceive that they or their family benefit from screening services for common conditions such as cancers. Therefore, the provision of such services is likely to receive widespread support, even if evidence of cost-effectiveness is weak, or indeed they might do more harm than good, as has been suggested for routine mammography. However, policies directed at poor lifestyle choices (e.g., smoking, alcoholism, and risky sexual behavior) may receive less popular support because the median voter does not perceive any personal or family need for such services. Even if the latter services are very cost effective, politicians seeking reelection may find it difficult to attach high priority to them. Similarly, many common healthcare interventions, such as treatment for acute myocardial infarction, hip and knee replacements, or cataract removals, are likely to be demanded by the median voter at a certain point in life. Following that line of argument, the median voter model cannot explain the success of HIV/AIDS interest groups in lobbying the governments, and it is interesting to note that for HIV/AIDS it stands in disagreement with the interest group model.

More generally, economic models of voting in health services have received little attention in the literature (Tuohy and Glied, 2011). In industrial democracies, an ageing population suggests that older people are becoming an increasingly important electoral force. Although an ageing population is itself partly the result of effective public health interventions, perversely, the preoccupation of older people is likely to be with curative rather than preventative interventions, compared with young people, reinforcing the tendency for politicians to favor health services over public health.

Bureaucratic Decision Making

The behavior of interest groups and voters can be understood only in terms of the institutional context in which they occur (Tuohy and Glied, 2011). Tullock’s (1965) and Niskanen’s (1971) institutional theories focus on the interests of ‘bureaucrats’ in maximizing their influence and the effect of their behavior on the level and nature of government output. Here the concept of the bureaucrat is interpreted broadly to embrace all public sector actors with significant influence over the allocation of resources. The essence of this approach is the belief that such bureaucrats receive power and remuneration in proportion to the size of their enterprise, with the implication that bloated, and inefficient public services emerge if there is a lack of effective control on the growth of government. Under the bureaucratic model, government agencies will seek to implement policies that maximize the size of their own enterprises and to undermine activities that are outside their direct control. They are able to do so because they have an informational advantage over their political counterparts. ‘Bureaucrats’ may therefore influence the pattern of healthcare expenditures in ways that do not accord with efficiency and equity considerations. If this model applies, it would also suggest substantial inertia in spending, making it difficult for politicians to change entrenched patterns of services.

It is difficult to find hard evidence, but the tendency of bureaucrats to maximize their own budgets and sphere of influence at the expense of others can be observed across many government sectors. For example, bureaucrats in health ministries often find it difficult to persuade bureaucrats in other ministries, such as education, to adopt policies designed to improve health, because of the reluctance of each sector to relinquish control. Public health, perhaps more than other government activities, requires collaboration across sectors and cross-departmental actions for which responsibilities cannot be clearly delineated.

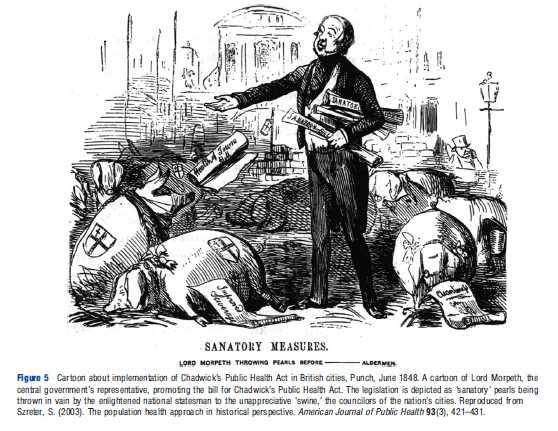

Multiple levels of governance add further complexities that affect variations in spending on public health, although the direction and magnitude of effects is likely to depend on specific funding arrangements for such policies (Tuohy and Glied, 2011). A system under which subnational governments make policy decisions, but a significant share of the associated costs is covered by the national government is likely to lead to higher investments in public health than a system under which national governments provide a fixed payment to subnational governments, which then bear the full marginal costs of the interventions. In a decentralized system of governance different levels of government are likely to free ride on interventions with public goods characteristics that are provided by other levels. More than 160 years ago implementation of basic sanitation measures was frustrated by tensions between central government and councilors of Britain’s large cities (Figure 5).

In the public sector services, it has also been argued that ‘street-level bureaucracy’ plays a powerful role in the way in which policy is implemented. The considerable degree of discretion accorded to healthcare workers (‘street-level bureaucrats’) in determining the nature, amount, and quality of services provided by their agencies has a powerful impact on the rationing of resources, and the factors governing their decisions might not be based on cost-effectiveness or similar principles.

Conclusion

The authors have considered three economic perspectives on public choice that help to explain why it has often proven difficult to obtain political backing for apparently commonsense public health interventions. The health and societal implications of many public health interventions can never be assessed in their entirety in advance of implementation. Even if they could, however, public health advocates have often found themselves in conflict with powerful interests groups, and politicians or bureaucrats who pursue their own objectives. This introduces an important and complex set of constraints into the priority-setting process, implying that available funds might be spent in particular areas or on specific programs determined by informational advantages or power structures within society. In general, such constraints will result in departures from conventional criteria such as cost-effectiveness rules.

Is it possible to counter those powerful influences? History has plenty of success stories. From the second half of the nineteenth century, Britain’s major cities embarked on a reform of the municipal social health amenities and social services that resulted in significant improvements in health. Historians believe that a class-bridging coalition between grass root organizations of the growing urban population, a new generation of civic leaders with social conscience that originated from the well-off urban elite, and a strong cadre of public service professionals, notably Medical Officers of Health, secured these reforms. Similar developments happened in other European countries and the USA.

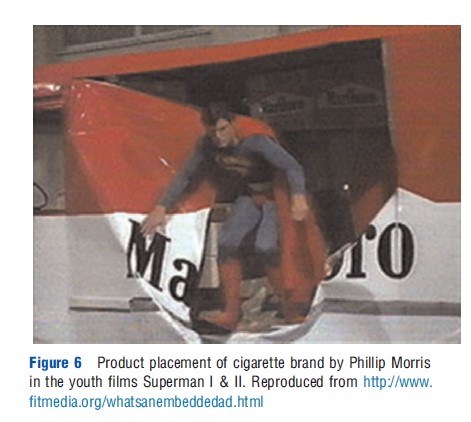

There are modern day examples of spirited initiatives by governments, government departments, or community organizations that instigated radical improvements in public health. For example, the outbreak of the plague in the Indian city of Surat in 1994 led to a decisive reorganization and introduction of stringent performance management of the civic waste department, named ‘transformation from AC to DC’ – making bureaucrats leave their ‘air conditioned’ offices to the ‘daily chore’ of direct supervision of waste management on site. The participatory budgeting model introduced in 1989 in the Brazilian city of Porto Alegre was an innovative reform program that successfully overcame severe inequality in living standards among city residents. Part of the program was introduction of participatory budgeting; community members now decide how to allocate part of the public budget. The recent decisive ruling of the Australian government on plain packaging laws for cigarettes is celebrated as a great success in the fight against cigarette smoking. For decades, the tobacco industry has successfully prevented such laws, to protect the value of their brands’ image, which they used more or less openly to link the brand with popular causes or films – such as the placement of Phillip Morris brands in Superman I and II, see Figure 6.

The authors have merely scratched the surface of this under-researched area of study. There is great scope for a much better understanding of decision-making behavior – both in low- and high-income countries – and a range of hypotheses can be tested by examining the priority-setting process itself and the resulting patterns of healthcare and public health expenditure. They would not challenge the desirability of seeking to maximize the health gains of the health system through the use of CEA. However, health economists have not yet taken advantage of the full range of economic approaches at their disposal. Only by securing a better understanding of the decision-making process can the impact of CEA be enhanced. They would argue that this can be achieved by augmenting the understanding of the political context of priority setting, using a variety of well-established models of political economy.

References:

- Anderson, G. M. (1999). Electoral limits. In Racheter, D. P. and Wagner, R. E. (eds.) Limiting Leviathan. Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

- Brownell, K. D. and Warner, K. E. (2009). The perils of ignoring history: Big tobacco played dirty and millions died. How similar is big food? Milbank Quarterly 87(1), 259–294.

- Glied, S. (2008). Public health and economics: Externalities, rivalries, excludability, and politics. In Colgrove, J., Markowitz, G. and Rosner, D. (eds.) The contested boundaries of American Public Health, pp. 15–31. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

- Hotelling, H. (1929). Stability in competition. Economic Journal 39(153), 41–57.

- Kar, D. and Freitas, S. (2011). Illicit financial flows from developing countries over the decade ending 2009. G. F. Integrity. Washington, DC: Global Financial Integrity. Available at: http://www.gfintegrity.org/ (accessed 11.06.13).

- Niskanen, W. A. (1971). Bureaucracy and representative government. Chicago: Aldine-Atherton.

- Sharma, L. L., Teret, S. P. and Brownell, K. D. (2010). The food industry and self-regulation: Standards to promote success and to avoid public health failures. American Journal of Public Health 100(2), 240–246.

- Stigler, G. (1971). The theory of economic regulation. Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science 3, 3–18.

- Szreter, S. (2003). The population health approach in historical perspective. American Journal of Public Health 93(3), 421–431.

- Tullock, G. (1965). The politics of bureaucracy. Washington, DC.

- Tuohy, C. H. and Glied, S. (2011). The political economy of health care. In Glied, S. and Smith, P. (eds.) The Oxford handbook of health economics, pp. 58–77. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mueller, D. (2003). Public choice III. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.