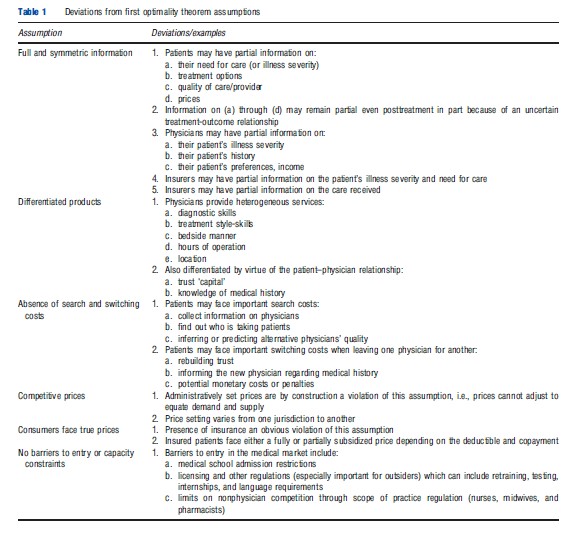

A market is generally defined as a set of firms or individuals selling similar (or at least partially substitutable) goods or services to a given set of consumers. Under some basic conditions, competitive markets yield Pareto optimal outcomes (The First Optimality Theorem). As a result, policymakers and regulators have generally favored competition and prohibited and punished anticompetitive behavior. However, many researchers have argued that: (1) many of the basic conditions required for the existence, and Pareto efficiency, of a competitive equilibrium are unlikely to be satisfied in the healthcare market and (2) in the presence of deviations from the necessary conditions, competition may actually be welfare decreasing. Important deviations from the model of perfect competition in the physician market include imperfect and asymmetric information, differentiated products, administratively set prices, insurance, and barriers to entry (Table 1). Simply put, conditional on being in a second-best world, the effect of competition on quality and cost of healthcare may not necessarily be positive.

Although clearly being different from markets that fit the requirements for perfect competition, the market for physician services does resemble other markets involving asymmetric information, expertise, or credence goods. Markets for car repair, legal advice, and taxicab rides are classic examples with the potential for inefficient outcomes and scope for government intervention. However, the market for medical care suffers from a larger number of imperfections than most, moving quite far from the first-best being a relevant welfare benchmark. In addition to the information asymmetries seen in these other markets, insurance and administratively set prices are notable attributes of the market for healthcare and physician services which complicate the welfare implications of competition and many of the conclusions drawn from nonhealthcare analyses.

Consistent with not using the first-best as the main point of reference, physicians have been seen by many (including lawmakers and courts) to be outside the scope of competition policy (in part because of their role as ‘learned professionals’ in the presence of imperfect information). In 1975, the US Supreme Court ruled that learned professionals (including physicians and the entire healthcare market) were indeed subject to antitrust laws, while nonetheless recognizing the particularities of the environment and the potentially perverse role of competition. In other countries, including Canada, Germany, and the Netherlands, lack of price competition among physicians is institutionalized as prices are explicitly negotiated between the government and physician associations.

Understanding several aspects of the economics of the physician market is necessary to address the aforementioned debate. First, what is the level of competition in the physicians’ marketplace? Second, what factors contribute to its relative strength? Third, what form does it take (e.g., price vs. quality competition)? The idea of competition in the physician market is relevant to all contexts and healthcare systems but its form and level are dependent on the institutional context (e.g., payment mechanisms and regulations regarding balance

billing) and the economic environment (e.g., the relative supply and demand of healthcare services). Although little empirical work exists investigating the market power of physicians or the welfare implications of reduced competition in the physicians’ market, examining the characteristics of the physicians’ market can provide a sense of the form and level of competition present in different jurisdictions.

Beyond describing competition in the physician market, its normative implications must be considered. In the context of the second best, it is unclear whether competition in the physician market will improve or harm social welfare. Theoretical work (Allard et al., 2009) has shown that, in a mixedpayment system, competition may provide appropriate incentives even in the presence of noncontractible effort, information asymmetry, unobserved heterogeneity, switching costs, uncertainty, and regulated prices. More specifically, competition makes a patient’s ‘threat’ to seek care elsewhere more credible, and may serve as an important incentive to provide appropriate care on both contractible and noncontractible dimensions. However, it may also lead to treatment heterogeneity, overtreatment (i.e., defensive medicine) and unstable physician–patient relationships. In this article the authors examine some of the aforementioned necessary conditions for the existence and Pareto efficiency of a competitive equilibrium as a first step to understanding the broader issue of competition and welfare in healthcare markets. The authors also review conclusions from the empirical research in this area.

To address these different issues, the authors start by defining the ‘players’ in the physicians’ market (i.e., who competes against whom), a key first step in any study of the level, form, or welfare impacts of competition in the physician market. The market is defined simultaneously by the set of suppliers and consumers in a geographic area, but geographic considerations and ‘firms’ will be discussed sequentially for ease of exposition. The authors first identify the set of consumers over which physicians (or other healthcare providers) compete (generally defined by a geographic area such as a zip code or Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA)). Next, to determine the level of competition within a given market, the services over which different types of providers might compete will be considered. Not surprisingly, physicians compete with providers of their own specialty but also across specialties and even with healthcare providers who are not physicians. Once the competitors and their potential customers are identified, the authors then separately examine the different elements that may limit competition. Although most of the empirical evidence discussed here is set in the North American context, this is primarily due to greater interest in physician competition there by researchers and policymakers. The general issues and theoretical frameworks discussed here are, however, common in many jurisdictions and the underlying economic principles remain the same.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. In Section Who Are the Patients/Consumers That Physicians Compete over?, the physicians market in terms of customers is examined, i.e., who do physicians compete over? In Section Who Competes against Whom?, the market in terms of sellers is discussed, considering the possibility that physicians may compete against nonphysician healthcare providers. In Section The Competitive Model, the authors discuss the necessary conditions for the existence of a Pareto efficient competitive equilibrium and corresponding welfare implications, and how the physicians’ market may deviate from such conditions. Conclusions are drawn and remarks made in Section Conclusion.

Who Are The Patients/Consumers That Physicians Compete Over?

Physicians compete over a set of potential patients, generally defined by their geographic location. Although such geographical areas may be simple to define (e.g., all physicians within a city limit are assumed to form one market), they may not accurately reflect the actual market. That is, the set of physicians that a patient will consider likely depends on several additional factors including: (1) the type (e.g., specialty) and quality of services provided, (2) the distance to travel, (3) whether a given provider is covered by the patient’s insurance, and (4) prices. For example, a patient may be willing to travel longer distances for nonemergency care than emergency care in order to get lower prices and/or greater quality and therefore considers seeking care from a wider set of physicians.

The question of prices that patients face is intricately tied to that of insurance for healthcare services. Because widespread, fairly comprehensive insurance coverage for physician services is the norm throughout developed countries, consumers of and payers for services are often not the same party. Physicians’ incomes can come from a mix of public and private payers (both insurance companies and individuals), one that varies significantly across countries, regions, and medical specialties, but rarely is comprised mostly of direct, out-of-pocket payment by patients. Insurers often restrict services they pay for to those provided by providers they contract with. In Canada, this means any physician participating in the provincial health insurance plan (nearly all physicians), whereas in the US, a managed care plan may have a more restrictive network of providers. As a result, the number of insurers in a market and the ways in which they steer patients to certain providers (if at all) can have implications for whether and how physicians compete for patients directly or whether they compete for contracts with insurers. Although the presence of insurance in general may make patients less responsive to price or quality differences across physicians (Section Insurance), payers can also play important roles in reducing information asymmetries between patients and physicians and can create direct incentives for patients to seek out higher quality physicians.

Relatively few empirical studies that quantify physician markets exist, but this question can be informed by the larger literature on competition in hospital markets which faces similar issues. Studies that use geographical areas like Primary MSAs or actual consumption patterns to define markets (i.e., competitors) suffer from creating barriers that patients often traverse and from generating bias if individuals choose a particular hospital based on unobservable characteristics like quality, which may also be correlated with market share. Take, for example, a physician who is of such low quality that they only attract patients in their immediate vicinity (e.g., in the immediate zip code). By calculating the market shares (and thus corresponding level of competition via a measure like HHI) using zip codes as markets, this physician may appear to face little competition (and thus benefit from a large market share). This conclusion, however, neglects the fact that many patients in neighboring zip codes may consider this particular physician as part of the choice set but choose not to seek care because of his or her poor quality. To deal with this potential bias, recent studies have used predicted market shares based on exogenous factors rather than actual shares.

Researchers who wish to define physicians’ markets and measure their degree of competition should consider similar potential biases. The authors are not, however, aware of any papers that estimate the level of competition in actual physicians’ markets in such a manner or which estimate individual physician’s market share. As a result, the discussion relies on geographical markets rather than estimated potential markets, although recognizing their limitations. Although not being the sole indicator of competition, the extent to which market characteristics (i.e., provider density) vary across jurisdictions can be instructive regarding the degree of competition.

Who Competes Against Whom?

Even once the geographic boundaries of a market have been defined, identifying who competes against whom in healthcare (and thus which providers constitute a particular market) is complicated by the fact that: (1) different types of providers will provide (im)perfect substitutes for each other and (2) different types of providers may have overlapping scopes of practice. Obviously, general practitioners (GPs) compete against other GPs, whereas obstetricians compete against other obstetricians (i.e., within-specialty competition). However, GPs may also compete with other specialists (from gynecology to psychiatry) as they have considerable overlap in their scope of practice.

Physicians may also compete across specialties because different types of specialists provide alternative treatments for the same health problem (e.g., ‘stenting’ by a cardiologist or bypass surgery by a cardiothoracic surgeon). As a result, when considering the market for a particular health problem or medical service, one may have to consider different types of physicians. Physicians may also compete with allied health professionals (AHPs) such as physician assistants (PA) and advanced practice nurses (APN) (which include nurse practitioners (NP), certified nurse–midwives, clinical nurse specialists and nurse anesthetists). Although the allowable scope of practice and level of independence of each of these groups varies from one jurisdiction to another, both have increased over the years. Dueker et al. (2005) found that in states where they are given a lot of professional independence, APNs have lower salaries (whereas their PA counterparts have higher salaries). They argue that this is because physicians in states where APNs are granted greater professional independence substitute away from APNs toward PAs in their hiring decisions for fear that they will take on greater roles in hospital settings. This is not surprising as the authors also find that greater independence of APNs negatively impacts physicians’ salaries. Finally, physicians are likely to compete with other ‘nonmedical’ healthcare providers such as chiropractors, osteopaths, and acupuncturists. As a consequence, a more complete vision of the market should consider these alternatives.

The legal context that frames the physician market includes licensing and scope of practice regulations. These largely determine the market, both geographically and with respect to specific services, and establish the ‘rules of the game’ in which competition flourishes (or doesn’t). These frameworks vary across jurisdictions, which can include an entire country (physician licensing and registration by the General Medical Council in the UK) or encompass states or provinces (provincial-level licensing in Canada). Although potentially helping to disseminate information and maintain or improve quality, these regulatory mechanisms are also likely to reduce competition, issues that will be discussed further in Section Limits to Supply and Barriers to Entry.

The Competitive Model

As noted previously, competitive environments yield Pareto efficient outcomes under specific conditions. If they are met, deviations from the competitive equilibrium lead to losses in social welfare. Because physicians provide differentiated services, entry into the market is strictly controlled, prices are often set administratively and patients generally do not face true prices because of insurance, physicians may have considerable market power. However, because the conditions underlying the First Welfare Theorem are unlikely to be met in the healthcare setting (Arrow, 1963), it is not obvious that such market power decreases welfare relative to greater competition.

In the context of concerns about physicians’ market power, accusations of collusion and anticompetitive behavior in the physicians’ market have become more prevalent and the US Department of Justice concluded that physician collusion when negotiating with third-party payers was in violation of the Sherman antitrust rules. Recent empirical work suggests that in spite of these prohibitions, physicians benefit from considerable market power. More specifically, Wong (1996) found that the GP and family physicians’ market is consistent with monopolistic competition (and not with monopoly or perfect competition), whereas Gunning and Sickles (2010) found that the medical and surgical specialists’ market is consistent with Cournot oligopoly.

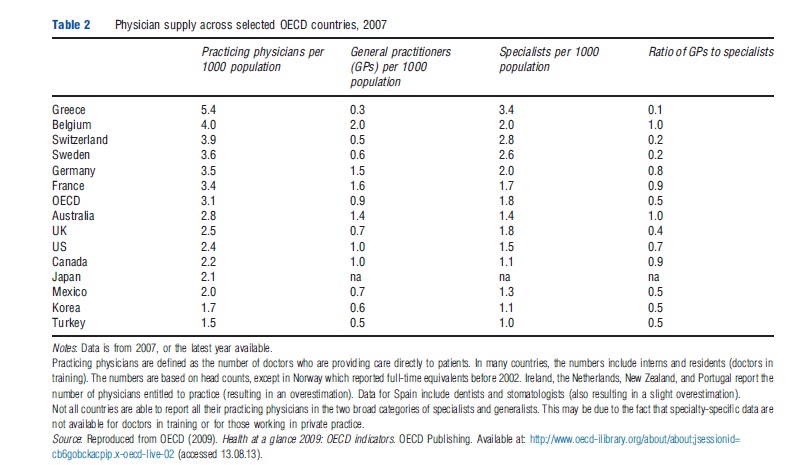

In the following subsections the authors discuss each of the conditions required for a competitive market to reach efficient outcomes in greater detail. Beforehand, however, the authors present some summary statistics on the density of different types of physicians across different jurisdictions in order to get a sense of the level of competition (or at least, how it may vary across different specialties and jurisdictions). Given that physicians are unlikely to vary greatly in terms of individual market shares, market-level HHIs are unlikely to provide much more information than simple concentration ratios.

Across Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, the number of physicians averaged 3 per 1000 population in 2007 and the average number of GPs was 0.9 per 1000 and 1.8 specialists per 1000. Considerable variation also exists across countries in each of these measures (Table 2). The number of physicians ranged from 1.5 per 1000 in Turkey to 5.5 per 1000 in Greece. Specialists greatly outnumbered generalists in central and eastern European countries and in Greece. Other countries, notably Belgium, France, and Portugal, have maintained a more equal balance between specialists and generalists. This variation in provider densities suggests differences in the degree of competition in physician markets across these jurisdictions.

The number of nurses averaged approximately 9 per 1000 population across OECD countries, ranging from 1.3 per 1000 in Turkey to 16 per 1000 in Denmark. The number of midwives averaged 72 per 100 000 women, ranging from 1 per 100 000 women in the US to 178 per 100 000 women in Australia. Such variation in the densities of providers that are complements and substitutes to physicians can also have implications for competition in the physician market.

Studies show that demographic factors such as age and gender can also have important implications for the supply of providers and level of competition, because those with different characteristics often practice in different locations (i.e., hospitals vs. private practice), work fewer or more hours, and select different specialties. In 2007, on average 40% of physicians across OECD countries were women, ranging from more than half of physicians in central and eastern European countries and Finland to less than 20% in Japan. The share of women physicians has increased from 29% in 1990 across the OECD and from 20% to 30% in the US between 1990 and 2007, and now account for nearly half of all medical students there (NCHS, 2009). Characteristics such as gender, age, and race are important predictors of specialty choice for some specialties but variation in expected income across specialties is also important.

A third factor that is linked to the competitiveness of the physician market is the issue of adequate physician supply, which remains an important policy topic especially with respect to urban/rural differences. For example, in the US the number of practicing physicians per 10 000 civilian population was 25.7 in 2008, but largely rural states like Wyoming and Idaho had only 18.7 and 17.0, respectively, whereas Massachusetts had 39.7 and Maryland had 35.3 (NCHS, 2011). Low physician-to-population ratios in rural jurisdictions mean that those providers face less competition from other physicians. Furthermore, the range of explicit policies and incentives that encourage physicians to locate in ‘underserved areas’ (e.g., the US National Health Service Corps, Quebec’s Differential Remuneration Program) clearly demonstrate that the market is not competitive in the sense that wages do not freely adjust to equilibrate supply and demand. Some of the factors that prevent such a wage adjustment are discussed in the following section.

Information And Physician Payment Methods

One of the defining characteristics of healthcare markets and the patient–physician relationship is the presence of incomplete and asymmetric information. Patients may have greater knowledge about their symptoms, habits, medical history etc., whereas physicians are likely to have privileged information about the patient’s illness and alternative treatment options. It is precisely because of their medical expertise that physicians act as their patients’ agent (i.e., they act on their patients’ behalf regarding medical decisions).

Under the traditional fee-for-service (FFS) system, physicians receive a fixed payment for each service they provide that is above the marginal cost of production. If physicians are paid via a blended payment (partial capitation plus FFS), or if there are multiple insurers across which physicians can cross-subsidize, FFS payments need not be above marginal cost (e.g., the US Medicaid program).

As a result, the FFS payment system rewards the volume of services. This incentive may lead physicians to manipulate information that they provide to their patients in order to encourage them to consume more care than they would chose themselves if they were fully informed. This implies patients would consume units of care whose marginal benefit is less than its marginal cost. The physician may manipulate the patients’ information, and thus their choice, by either exaggerating the illness severity or the need for care. This phenomenon is known as supplier-induced demand (SID). If patients’ demand is responsive to the quality of services, then FFS may also reward quality via volume. Of course, the distinction between quality that improves the value of healthcare services versus amenities that are perceived by patients as higher quality but do little to improve value beyond patient satisfaction is an important one.

Several theoretical models and empirical analyses tackle this issue. In a classic article, McGuire and Pauly (1991) presented a model of healthcare provision and costly inducement of care. In a setting with only one type of care (or patient), they show that physicians will wish to induce care in the presence of a decreased fee (in order to recoup lost earnings) only if the income effect dominates the substitution effect. In the thoracic surgery setting, one study found that surgeons whose fees were reduced under Medicare recouped some of the lost earnings by increasing the number of surgeries they performed.

McGuire and Pauly‘s model has two types of patients, with private or Medicare health insurance coverage, each with their respective reimbursement rate. They show that a decrease in one reimbursement rate (i.e., the Medicare fee) can lead to an increase in the amount of care provided to the now more generously reimbursed patient (i.e., those with private insurance), again if the income effect dominates. Another study found that obstetricians who faced more competition (through falling birth rates) responded to the potential reduction in their income by inducing demand for cesarean deliveries (which are more lucrative than vaginal births).

To reduce this incentive for volume, alternative forms of physician payments such as capitation and salary have been introduced. In a capitation system, physicians receive a fixed payment for each patient they enroll in their practice in exchange for care for a given period of time without any marginal reimbursement. By not tying a physician’s income to volume, the capitation payment system completely eliminates the incentive to provide inefficiently high levels of care. Although this may reduce or eliminate SID, it has been associated with reduced quality and quantity of care (i.e., physicians may wish to manipulate information not to encourage care but rather discourage it). One study found that the increase in managed care has limited some of physicians’ ability to induce care via supply-side constraints. Similarly, salaried physicians have no incentive to induce care but may have little incentive to provide the appropriate quantity and quality of care (as their income is invariant, at least in the short run, to such decisions). Although less competitive markets may allow physicians to exploit their market power (say, through SID) their willingness to do so will depend, in part, on the way that they are paid.

Differentiated Medical Services And Switching Costs

Although physicians may provide similar sets of services, they are likely to be different along several dimensions like quality (including time spent with the patient, diagnostic skills, treatment recommendations, bedside manner). Even in the presence of a common specialty and types and levels of quality, patients are unlikely to see their physicians as perfect substitutes by simple virtue of the patient–physician relationship. More specifically, patients may have developed a sense of trust with their regular physician. Furthermore, the physician is likely to have privileged information regarding the patient’s health history and need for care. Because of these aspects, patients may face important switching costs when seeking care from an alternate provider and physicians are likely to exert some degree of market power. One way physicians may exploit such market power would be to price discriminate across patients. It is precisely the potential for this behavior that is at the root of uniform administrative pricing for physician services. Although administratively set prices eliminate physicians’ ability to price discriminate, they may nonetheless exploit their market power through other means (which in turn will depend on the level of competition). The authors discuss this issue in the next section.

Fee Setting And Organizational Response

The presence of administratively set prices is by definition a deviation from a competitive environment. Although administratively set prices may limit physicians’ ability to exploit their market power through price discrimination (and thus, may in fact be welfare enhancing), it does not necessarily prevent physicians from exploiting the heterogeneity and nontradability of their services or the presence of switching costs (and this even in the presence of perfect information). By simply giving patients a ‘take-it-or-leave-it’ offer on the quantity of care to be provided, the physician may convince the patient to consume excessive amounts of care (i.e., yield higher profits for the physician and lower patient welfare; McGuire, 2000). For example, consider a patient who can consume care at p dollars per unit q. Further suppose that the patient’s net benefit from consuming the utility maximizing amount of care is given by B(q)-pq. Now suppose that the patient faces a switching cost k if they decide to leave their current physician for an alternative who would be willing to provide q units (also at p). Switching costs could be monetary if tests or procedures need to be redone, or psychic in the sense of building a relationship with a new physician. If the patient leaves their current physician for an alternative one, they then receive a net benefit of B(q)-pq-k. Thus, the current physician can persuade the patient to consume q` units of care (greater than q) as long as B(q`)-pq`>B(q)- pq-k. Thus, in the presence of administratively set prices, nontradable goods, and switching costs, physicians may hold important market power even in the presence of full information. The above suggests that increasing the patient’s ability to move from one physician to another (i.e., decreasing the switching costs) is likely to yield important implications on physicians’ market power and patient welfare (which is consistent with previous work (Allard et al., 2009)). As a result, one could imagine that the presence of portable medical records and increased patient education may have important benefits in encouraging an efficient provision of care.

How the fees are actually set and how closely they reflect marginal cost pricing is also an important issue. In several systems, payment rates are primarily based on relative weights that reflect the costs of inputs used to provide physician services and a conversion factor which translates these weights into dollar amounts. The weights reflect factors such as physician work (time, effort, skill, etc.), practice expenses (rent, equipment, and staff), and professional liability insurance expenses and the medical profession often exerts significant control in determining them. Governments can use (or attempt to use) adjustments to conversion factors to limit spending on physician services and to constrain spending growth (e.g., US Medicare’s Sustainable Growth Rate system).

In many jurisdictions, physicians have played an important role in setting these rates. In Canadian provinces, provincial physician associations negotiate directly with their respective governments to set the fees – fees which then apply to all physicians. In Germany, decisions made both by a government committee at the federal level and by regional physicians’ associations affect the amounts physicians are paid for the services they provide to patients. In the US, however, reimbursement rates paid to the same physician can vary between insurance providers. For example, a physician might receive different reimbursement rates for the same procedure depending on the patient’s (governmental or nongovernmental) insurer (from Medicare, to Medicaid, to private insurers). Furthermore, physicians are prohibited of collectively bargaining when negotiating reimbursement fees.

One of the ways that insurers have reduced the fees paid to physicians is through Managed Care Organizations (MCO). MCOs control costs through a variety of tools including selective contracting. Selective contracting refers to limits imposed on the pool of physicians that enrolled patients can consult with (i.e., a network of providers). By limiting their enrolees’ access to providers, MCOs gain bargaining power relative to physicians. Although very strict forms of restrictive contracting were popular in the early years of managed care, less restrictive contracts such as Preferred Provider Organizations are more common now. These forms of managed care contracting also coexist with ‘any willing provider’ laws, which require managed care plans to explicitly state their evaluation criteria and to accept any qualified provider who is willing to accept the plan’s terms and conditions. Selective contracting and ‘any willing provider’ laws are clearly designed to have opposing effects on competition in the physician market.

In response to the potential negative effects of MCOs on physician earnings, physicians have introduced different organizational structures in order to reduce costs or increase their bargaining power. Independent Practice Associations are networks of independent physicians that contract with MCOs and employers. Physician-Hospital Organizations, however, are joint ventures between hospitals and physicians. Emerging Accountable Care Organizations are networks of physicians or physicians and hospitals that contract with insurers. Although such networks may provide important efficiency gains, they run the risk of antitrust violations. Accordingly, 2010 legislation in the US prevents new physician-owned hospitals from being built and puts strict limits on already existing ones given the physician’s obvious conflict of interest (and corresponding evidence that they may cherry-pick customers, avoid costly services and provide low quality of care).

Insurance

In many markets, consumers face a price that reflects the cost of production when making purchasing decisions. This is usually not the case in the medical services market however because of the presence of insurance. With insurance, consumers face a partially or fully subsidized price and they will wish to consume care until the marginal benefit of care is equal to their subsidized cost (i.e., their out-of-pocket cost) and not the actual marginal cost of production – a phenomenon known as ex post moral hazard. As a result, insurance can cause important deviations from the Pareto efficient outcome. To reduce this problem of ex post moral hazard (and thus, limit also its perverse effect) one can simply increase the share of the expense the patient pays for (i.e., increase the copayment). By doing so, however, one reduces the risk-spreading benefits of insurance.

Limits To Supply And Barriers To Entry

The condition of free entry is clearly not met in the case of the physician market, with significant barriers existing in training, licensure, and migration across jurisdictions. Nearly all OECD countries exercise some form of control over the number of medical school students – often in the form of a numerus clausus, or limit on the number of medical school slots – or residency positions. This is motivated by a variety of factors including restricting medical school entry to the most able applicants, controlling the total number of physicians for costcontainment reasons, and limiting the direct cost of training. Although countries vary in their approaches to these limits (i.e., ministerial decisionmaking vs. financial incentives) and the extent to which control is devolved to subnational governments (state/provincial/canton) or medical schools themselves, the net result is that the number of physicians is largely determined by policy.

Beyond the total number of physicians, the mix of physicians in different specialties is a function of the number of residency slots, which is largely determined by organized medicine. In the US, Residency Review Committees, consisting primarily of physicians from a particular specialty, control the number of residents who train in, and therefore the number of physicians who flow into, each specialty. Nicholson (2003) showed that these committees could set the flow of residents in order to achieve their desired combination of licensed physicians and physician rents and that minimum wage regulation and scarcity of teaching material (i.e., patients) could also result in the observed persistent excess rates of return to specialization.

After medical education and residency training are completed, entry into the market for both physicians and AHPs is restricted via licensing and practice regulations that can limit competition geographically and in terms of specific services provided. Three primary mechanisms are used to regulate physicians and AHPs, licensure, certification, and registration, and in the US this occurs at the state level. Licensure involves a mandatory system of state-imposed standards that practitioners must meet to legally practice within the state. Nongovernmental boards, dominated by members of the regulated profession but often also including political appointees or members of the public, determine applicants’ eligibility requirements, develop standards of practice, and enforce disciplinary actions. Certification refers to a voluntary system of standards, usually set by nongovernmental agencies or associations. Physicians may become board certified within a specialty to establish they have the appropriate level of knowledge and skills in that area. Registration is the least restrictive mechanism, requiring practitioners to file their name, address, and qualifications with a government agency in order to practice, but not to meet any additional educational or experience requirements.

As discussed in Section Who Competes against Whom?, competition in the market for physician services is also affected by nonphysician providers, the extent to which they are complements to or substitutes for physicians, and the laws and regulations that govern the range of services they provide and how they are remunerated. Feldstein (1988) describes how organized medicine has influenced the demand for, and supply of, physician services, notably by encouraging insurance coverage for their services, disallowing price competition among members, and restricting (expanding) the scope of practice of substitute (complementary) providers allowed under state practice acts. He also describes similar efforts by the American Dental Association, American Nurses Association, and American Hospital Association on behalf of their memberships. For example, the American Medical Association has favored the use of foreign medical graduates to serve as interns and residents (complements, because the physician bills for services provided) and also their return to their home country once their residencies are completed and they become substitutes. Similar tensions are seen between physicians and PA, NP, and chiropractors. Beyond limiting the legal scope of practice of substitute providers, efforts to exclude their payment by a third party has often occurred in the context of public insurance programs (US Medicare, Canadian provincial plans, etc.).

The last barrier to entry considered here is migration, or physical entry into the physician market. Internationally, OECD countries have adopted specific policies designed to stimulate immigration of foreign physicians although respecting the constraints of licensing requirements, protection of vested interests by domestic physicians, and minimization of any negative impacts on the home country. Even within countries, state, or provincial-level licensing requirements mean that physicians may face considerable barriers to practicing in another jurisdiction.

Conclusion

In this article the authors provided an overview of the physicians’ market and the role of competition within it. Specifically, the authors noted that although the idea of competition is relevant in all contexts, the observed level and form of competition in any market for physician services will depend on the institutional context and the economic environment.

Although the authors empirically observe indicators of the degree of competition in the physician market to vary across contexts, whether a lack of competition decreases social welfare remains an open question. The uncertainty regarding competition’s impact on welfare in this market stems from the numerous market failures discussed in Section The Competitive Model. Although some of these deviations from the competitive model are likely inherent to markets for ‘expert’ services (information asymmetries, search and switching costs), others are more amenable to change via health policy and regulation (insurance, limits on entry, price competition, and provision of services by other providers).

In this second-best environment, the value of competition as a tool to increase welfare is unclear. Whether competition is welfare decreasing depends on the context, specifically how many market imperfections exist and how big are they? Put another way, how far are we from the first best? Competition may be a positive if it encourages the provision of high-quality care (e.g., heterogeneous physicians provide an appropriate mix and levels of care in the presence of information asymmetry and insurance). Competition may be undesirable if it encourages the wasteful use of resources in attracting and treating patients or increases the quantity of services without corresponding reductions in administered prices. For example, Kessler and McClellan (2000) empirically examined the impacts of competition in US hospital markets and found that, in that specific context and time, competition improved welfare. The authors expect that similar work to better understand the implications of physician competition, taking into account the specific institutional and economic contexts, will also be valuable.

Acknowledgment

Strumpf gratefully acknowledges funding support from a Chercheure Boursiere Junior 1 from the Fonds de la Recherche du Quebec – Sante´ and the Ministe`re de la Santeet des Services sociaux du Quebec. Leger thanks HEC Montre´ al for funding.

References:

- Allard, M., Leger, P. T. and Rochaix, L. (2009). Provider competition in a dynamic setting. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy 18, 457–486.

- Arrow, K. (1963). Uncertainty and the welfare economics of medical care. American Economic Review 53(5), 941–973.

- Dueker, M. J., Jacox, A. K., Kalist, D. E. and Spurr, S. J. (2005). The practice boundaries of advanced practice nurses: An economic and legal analysis. Journal of Regulatory Economics 27(3), 309–329.

- Feldstein, P. J. (1988). The politics of health legislation: An economic perspective. Ann Arbor: Health Administration Press.

- Gunning, T. S. and Sickles, R. C. (2010). Competition and market power in physician private practices. Mimeo. Rice University.

- Kessler, D. P. and McClellan, M. (2000). Is hospital competition socially wasteful? Quarterly Journal of Economics 115(2), 577–615.

- McGuire, T. G. (2000). Physician agency. In Culyer, A. J. and Newhouse, J. P. (eds.) The handbook of health economics, pp. 461–536. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- McGuire, T. G. and Pauly, M. V. (1991). Physician response to fee changes with multiple payers. Journal of Health Economics 10(4), 385–410.

- National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) (2009). Health, United States, 2008. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

- National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) (2011). Health, United States, 2010: With special feature on death and dying. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

- Nicholson, S. (2003). Barriers to entering medical specialties. NBER Working Paper #9649. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Wong, H. S. (1996). Market structure and the role of consumer information in the physician services industry: An empirical test. Journal of Health Economics 15, 139–160.

- Blevins, S. A. (1995). The medical monopoly: Protecting consumers or limiting competition? Policy Analysis No. 246. Washington, DC: Cato Institute.

- Federal Trade Commission and Department of Justice (2004). Improving healthcare: A dose of competition. A report by the Federal Trade Commission and The Department of Justice, 2004.

- Gaynor, M., Haas-Wilson, D. and Vogt, W. (2000). Are invisible hands good hands? Moral hazard, competition and the second best in health care markets. Journal of Political Economy 108, 992–1005.

- Gaynor, M. and Town, R. (2011). Competition in health care supply. In Pauly, M. V., McGuire, T. G. and Barros, P. P. (eds.) The handbook of health economics, vol. 2, ch. 9. North Holland: Elsevier Science.

- Gruber, J. and Owings, M. (1996). Physician financial incentives and caesarean section delivery. RAND Journal of Economics 27, 99–123.

- Yip, W. (1998). Physician responses to medical fee reductions: Changes in volume of supply of coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgeries in the medicare and private sector. Journal of Health Economics 7, 675–700.

- https://www.oecd.org/health/ Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development.