In recent years there has been a surge in interest in models of imperfect competition in the labor market, and monopsony in particular (Boal and Ransom, 1997; Bhaskar et al., 2002; Manning, 2003; Ashenfelter et al., 2010; Manning, 2011). The term ‘monopsony’ was introduced by Joan Robinson in her 1933 book The Economics of Imperfect Competition. Taken literally, monopsony means a situation with only one buyer in a labor market and textbook discussions of Robinson’s theory have accordingly been largely confined to ‘company town’ examples such as a coal mine in a rural town that is the only local employer. But Robinson’s discussion makes it clear that monopsony power allowing employers to set wages may exist whenever frictions in the labor market give rise to an upward sloping labor supply (LS) curve at the individual firm level. (In this light, recent allusions to a ‘new monopsony’ framework represent a new shift of attention amongst sources of monopsony enumerated in Robinson’s original discussion rather than new conceptual insights. Of course theoretical developments in the interim, particularly in the area of search theory, have helped make information related frictions more salient as a potential source of monopsony.) Such frictions might arise because ‘‘there may be a certain number of workers in the immediate neighborhood and to attract those from further afield it may be necessary to pay a wage equal to what they can earn near home plus their fares to and fro; or there may be workers attached to the firm by preference or custom and to attract others it may be necessary to pay a higher wage. Or ignorance may prevent workers from moving from one firm to another in response to differences in the wages offered by the different firms’’ (Robinson, 1933, p. 296).

Writing in 1946, Lloyd Reynolds predicted ‘‘The view that labor-market imperfections result in a forward-rising supply curve of labor to the firm… first elaborated by Mrs. Robinson… seems well on the way to being generally accepted as a substitute for the horizontal supply curve of earlier‘‘ (Reynolds, 1946, p. 390). But despite this early enthusiasm, monopsony models have rarely been invoked to characterize important segments of the US labor market, as the ‘company town’ metaphor led many economists to dismiss their broader relevance. One important exception is the labor market for registered nurses (RNs), where Yett (1970) suggested that monopsony was the most likely explanation for the consistent nurse ‘shortages’ reported by hospitals at least since World War II. To Yett, and many economists since, oligopsony seemed a natural model for the nurse labor market since many hospitals operate in counties with few other hospital competitors for workers, and there are reasons to believe that the geographic and occupational mobility of nurses is low. Indeed, the lion’s share of empirical papers directly investigating the predictions of monopsony models cited in three recent reviews of the literature involve the nursing labor market (Boal and Ransom, 1997; Manning, 2003, 2011). (The only other occupation frequently featured in the monopsony literature is teachers (Landon and Baird, 1971; Boal, 2009; Falch, 2010).

In this brief research synthesis, it is attempted to illustrate why health labor markets so often evoke monopsony models to economists and review the empirical evidence on their relevance. Nearly all the relevant empirical literature concerns nurses, so it will largely be confined to the discussion of the same. It is started by providing a sketch of different models that imply an upward sloping LS curve, and thus some market power, for individual employers. It will be seen that these models provide an alternative, and arguably more persuasive explanation for several empirical facts that neoclassical models have struggled to rationalize. For example Manning (2003) argues that vacancies, wage dispersion across firms for similar workers, and employer provision of general skills training are all suggestive of monopsony. The second Section Suggestive Evidence therefore presents some facts about the nurse labor market with an eye toward assessing such a prima facie case for the plausibility of monopsony. Since many of these facts can be explained in a neoclassical framework, their existence does not constitute a ‘severe test’ (Mayo, 1996) of whether the labor market is monopsonistic. The third section reviews how economists have attempted to test for monopsony and assess the overall body of evidence. It is ended by discussing some areas that might be fruitful avenues for future research.

Why might we care whether monoposony is a better model of labor markets in health care? One reason is simply that monopsony models may provide a more accurate explanation for why many labor market phenomena, such as wage dispersion, vacancies, or large employers paying higher wages are observed (Manning, 2011, 2003). But the extent of monopsony power in the market also has important consequences for public policy. The implication of most monopsony models is that wages will be set lower in equilibrium than would be the case under perfect competition. If so, then labor will be inefficiently allocated across nursing and nonnursing sectors with too few nurses, obviously a concern in the context of the nursing shortages that have continued well past Yett’s study and into the present. Some researchers in this area have suggested that the government should therefore be more active in monitoring nurse compensation, or perhaps promote unionization or a mandated wage to provide countervailing power to nurses in wage setting. Another public policy area where the extent of monopsony is important is the large public investment in nurse education. If employers are able to capture a substantial portion of the returns to nurses’ human capital investments due to their ability to set wages below marginal products, then government subsidies may be less attractive relative to relying on private employers to pay for (part of) nurse training.

Models And Predictions

Since by now there are many excellent survey treatments of the various models implying monopsony power, here only a short sketch of some of these models and their empirical predictions is provided (Boal and Ransom, 1997; Bhaskar et al., 2002; Manning, 2003, 2011). In a perfectly competitive labor market workers are fully informed about the wage offerings of alternate employers, other jobs that are perfect substitutes for their own are readily available, and job mobility is costless. Under these assumptions, the LS curve facing a firm is infinitely elastic because a firm reducing their wage even slightly will see all its workers leave to work for other firms. At the same time, employers have no reason to offer anything above the market wage, since they can get all the workers they need at that wage. The monopsony models discussed in this section are all concerned with explaining why these assumptions might not be satisfied.

Employer Concentration Or Collusion

The most straightforward case of monopsony arises when a single firm constitutes the only buyer of labor in a particular market. The classic work of Bunting (1962) showed that high employer concentrations were rare for the US labor market as a whole, leading many economists to dismiss the relevance of this type of model. In health care, however, this isolated firm model may apply more frequently as many hospitals operate in counties with few other competitors for nurse labor. (Of course, even in rural areas significant alternate employment opportunities may exist for nurses in doctors’ offices, schools, etc.)

With a single employer for an occupation, the LS curve to the firm is the supply curve for the whole market. The market supply curve is typically assumed upward sloping, reflecting the idea that higher wages should induce more workers of that occupation to enter the labor market of the area, or workers already in the area to switch to the occupation in question. As described in Section Nurse Labor Supply, economists have presumed this elasticity to be low for nurses, making it more likely they might be vulnerable to being ‘exploited’ – in a sense defined below – by a monopsonistic employer.

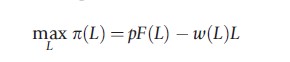

Assuming a firm produces its output using only labor (L) its profit maximization problem can be written as

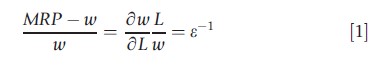

where π(·) is firm profit, F(·) is the firm production function or revenue normalizing output price to unity, and w(L) is the wage required to attract L workers (i.e., the LS function). The first-order conditions of this problem imply the following wage-setting rule

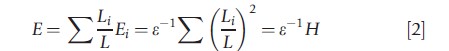

where MRP is the firm’s marginal revenue product, t is the elasticity of LS with respect to the wage. Unless the LS curve is perfectly elastic, eqn [1] suggests that the monopsonist will pay workers less than their marginal revenue product, and employment will be lower than in the perfectly competitive case. Since Pigou (1924), economists have sometimes called the ratio on the left of eqn [2], the ‘rate of exploitation’, referred to below as E. Note that a nearly identical result can be derived from a model with multiple firms in the same market that collude to maximize joint profits (Boal and Ransom, 1997, p. 91).

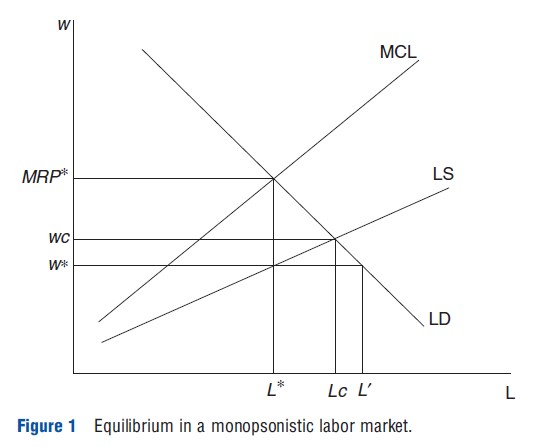

Robinson’s classic graphical analysis of equilibrium in a monopsonistic labor market is depicted in Figure 1. With an upward sloping LS curve, the marginal cost of hiring labor (MCL) lies above the LS curve so long as the employer must pay workers the same wage (i.e., cannot perfectly wagediscriminate). Thus, the employer hires workers up until the marginal cost of doing so equals the value of the marginal revenue product at L*. As described above, there will be a gap between wages (w*) and workers’ marginal revenue product (MRP*). But note also that at the wage prevailing in equilibrium, labor demand exceeds LS. In other words, firms face a shortage of labor, or ‘vacancies’ (Archibald, 1954), equal to L`-L*. This is still an equilibrium because in fact firms cannot hire additional workers at the wage w* as workers demand higher wages to increase their supply – in other words, firms are ‘(labor) supply constrained’. In this model, minimum wage policies that raise wages above w* and as high as MRP* can increase both employment and wages.

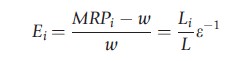

With a few large employers in the market, the situation might best be thought of in terms of oligopsony where there may not be collusion but employers do consider other firms’ actions in their hiring decisions. The Cournot model provides a tidy analytical result: if employers choose labor to maximize profits taking other firms’ employment levels as given, the first order conditions of the model suggest an employer-specific Ei equal to

and thus an average (employment-weighted) market level E of

where H is the Herfindahl index of employment concentration. The latter condition suggests a relationship between the level of exploitation (and thus wages) at the market level and the concentration of employment so long as the inverse LS elasticity is nonzero (i.e., so long as the labor market is not perfectly competitive). Note, however, that correlations across markets between H and wages are only indicative of monopsony power if total labor demand (i.e., the sum of firms’ MRP) and LS are held constant.

What testable predictions arise from models of employer concentration or collusion? The most frequently explored prediction in the empirical literature is the idea that across markets, higher concentration should lead to greater ‘exploitation’ and lower wages. In part, such a prediction is generated by the assumption that collusion between employers is more likely to be enforceable with relatively few actors. Although intuitive, it’s important to keep in mind that this assumption has little empirical evidence behind it – little is known about the prevalence of collusive agreements among employers across market structures. Short of collusion, models of oligopsony do generally predict a relationship between concentration and wage levels like eqn [2] above. It is important to remember that this prediction discriminates between competition and monopsony only if market level labor demand and supply are held constant. In general, markets that are more concentrated (e.g., rural areas) may differ along both of these lines leading to indeterminate biases – unaccounted for differences in demand would tend to amplify any negative correlation between concentration and wages, whereas differences in supply would tend to lead to a positive bias. (These presumptions about the direction of correlation are based on the assumption that areas with more concentrated employment probably have lower unobserved demand and supply shocks.)

Worker Or Firm Heterogeneity

Another source of employer market power is that alternate firms may not be viewed as perfect substitutes in the eyes of job seekers due to differences in worker preference or differentiation amongst firms. Bhaskar et al. (2002) present an intuitive model that illustrates the idea, and a similar idea is developed by Staiger et al. (2010) in their analysis of the market for RNs, discussed below. (Also see Bhaskar and To (1999) for a more detailed exposition of the model.) In their model, workers are uniformly distributed along a 1 km road with two firms (firm 0 and firm 1) located at either end. The cost of transportation to and from the work is t per kilometer, so a worker who lives x kilometers from firm 0 incurs a cost tx if he works for firm 0 and t(1 – x) if he works for firm 1. Thus, transportation costs differentiate the desirability of employment at the two firms for a given worker’s location. If both firms paid identical wages, then all else equal workers would simply choose to work for the nearest employer. If firm 0 increased its wage by a small amount and firm 1 did not, it would attract more workers from firm 1 but clearly not all of them because a small wage increase would not be enough to compensate workers who live close to firm 1 for their cost of travel. Instead, LS would vary continuously and positively with the wage. The greater is t, the transportation cost parameter, the greater a wage increase will be necessary to increase LS for each firm and conversely with t=0 the supply curve will be perfectly elastic.

It should be clear here that transportation costs are simply a metaphor for some nonwage aspect of a job that affects the relative utility workers derive from employment at a particular employer. In nursing markets it is easy to imagine many such dimensions along which jobs might differ, including not only geography but also workload (patients per day), control over their work hours, the quality of facilities, etc. Perhaps less information is available regarding how much these other job aspects affect LS decisions – in other words, what is the magnitude of t for these aspects?

Equilibrium Search

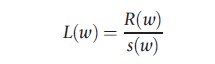

Another strand of the literature on monopsony invokes search frictions as the cause of firm-level upward sloping LS curves. Search models provide an alternative, dynamic way of viewing firm-level LS. A firm’s level of employment Lt can be written in terms of its previous level of employment, the separation rate of employees from the firm s(wt), and the number new recruits R(wt):

![]()

In this context, wages influence the size of the firm through the flows of workers to and from the firm. In steady state, the dynamic LS equation can be written

or in elasticity terms,

![]()

In other words, the LS elasticity to the firm can be estimated as the difference between the elasticity of new recruits and the elasticity of the quit rate with respect to the firm’s wage (Card and Krueger, 1995). Manning (2003) suggests the simplification of assuming the elasticities on the right-hand side of eqn [3] are equal in magnitude, so the elasticity of LS is just twice the elasticity of separations with respect to the wage. In this light, a firm has market power whenever the elasticities of recruits or separations are less than infinite.

The model of Burdett and Mortensen (1998) is commonly invoked in this literature, and is striking in that it shows that a lack of perfect information (i.e., a finite job offer arrival rate) can generate monopsony power for firms even with identical workers and infinitely many small firms. (See Manning 2003) for a simplified presentation of this model and discussion.) One key result of the model is that the ratio of the job arrival rate to the separation rate indexes the degree of market power firms possess in a market. Manning (2003, p. 44) shows that this parameter is monotonically (negatively) related to the fraction of new hires (recruits) who come from nonemployment, and so the latter is positively related to the extent of monopsony in the market. The intuition is that the higher the fraction of new recruits coming from nonemployment, the less is the direct competition among employers for workers as fewer workers are leaving one firm for another.

Suggestive Evidence

The models of monopsony outlined in the Section Equilibrium Search all suggest a variety of symptoms that might suggest their presence in the labor market. Before turning to a review of the literature formally testing the implications of such models, it is perhaps useful to review some features of the nurse labor market that hint at either the motivations or the predictions of these models. This evidence is suggestive, and meant only to encourage the reader to view the nursing market through a monopsonistic lens, as it has led many economists to do already. The literature that more formally tests the monopsony hypothesis is reviewed in the following section.

A preliminary note is that since nearly all of the empirical studies of monopsony in health labor markets use data from the US, international comparison is not provided. Although the basic forces at play in other developed countries are likely to be the same as those identified in the theoretical discussion in the Section Equilibrium Search, there are reasons to believe the degree of monopsony power for employers in other countries may differ from that found for firms in the US. For example, Acemoglu and Pischke (1999) argue that lower labor mobility in Germany gives firms there more monopsony power than in the US and helps explain the higher prevalence of employer sponsored training in Germany. It seems likely that differences in labor markets in the US and other developed countries like this exist in health care as well, so the discussion in this section should be viewed in this light.

Vacancies

More than any other feature, the presence of nurse-shortages evidenced by high vacancy rates has motivated the prima facie case that nurse labor markets are monopsonistic. Since the 1950s, hospitals have reported RN vacancy rates ranging as high as 10–20% (Yett, 1970; Buerhaus et al., 2009). Amongst economists, early explanations for such shortages suggested that they reflected a state of dynamic disequilibrium whereby increases in the demand for nurses were constantly outpacing increases in supply, and wages were adjusting only slowly. Thus, at the (lagging) wage prevailing in the market, demand for nurses frequently exceeded supply (Blank and Stigler, 1957; Arrow and Capron, 1959). Invoking the work of Archibald (1954) who wrote ‘‘we will find oligopsony in the labour market whenever there are few employers of a given type of labour in an area and the cost of mobility is positive,’’ Yett (1970) argued instead that hospitals were oligopsonists and so vacancies could exist even in equilibrium whatever dynamic (out of equilibrium) shortages may or may not be occurring in addition.

Although comprehensive national data are not available, more recent statistics suggest that relatively high vacancy rates persist for several types of nurses across a range of employment settings. A 2010 survey of 572 community hospital CEOs by the American Hospital Survey found RN, licensed practical nurse (LPN), and nurse aide vacancy rates of 4%, 4%, and 5%, respectively, which is low by historical standards due to the recession causing more nurses to join the labor force (Association, 2010). (One should be cautious about comparing reports of vacancy rates across different information sources, as the definitions used appear to vary significantly.) Among nursing homes, a 2007 survey found vacancy rates of 16.3%, 11.1%, and 9.5% for RNs, licensed practitioner nurses, and certified nurse assistants, respectively. (This is based on information from 3828 responding nursing homes from a 2007 survey of all 15 558 nursing homes in the US conducted by the American Health Care Association (Table 1, http://www.ahcancal.org/research_data/staffing/Documents/Vacancy_Turnover_ Survey2007.pdf%20accessed%20May%2030,%202011).)

Concentration And Collusion

Another aspect of the nurse labor market that has evoked monopsony models is the relatively high employment concentration ratios. Yett (1970) suggested that the emergence of nursing shortages coincided with consolidation of RN employment in hospitals around World War II, and it remains true that the plurality of RNs work for hospitals. Many hospitals, in turn, operate in labor markets with few other employers: Yett (1970, p. 378) cites the figure that 60% of hospitals are in a health service area with fewer than six hospitals. More recent statistics suggest approximately 60% of US counties are served by only one hospital and approximately 25% of all hospitals are the only hospital in their county. (Author’s tabulations of 2004 Area Resource File data. Of course hospitals are not the only employer of nurses but, especially in less populous counties, they account for the lion’s share of employment.) That said, there are other employers of nurses such as nursing homes, doctors offices, schools, etc. and their presence in even the most rural markets may provide enough competition to prevent nurse exploitation in the sense of eqn [1].

Arguably the most direct evidence on monopsony would be the discovery of explicit agreements amongst employers to lower wages. Although economists tend to be skeptical of the sustainability of such arrangements among any substantial number of employers (For an early example, see Rosen (1970). He was also skeptical that hospitals, as nonprofit organizations, would engage in such rent appropriating behavior – a concern echoed by Pauly (1969). A classic reference is Stigler (1964).), there is scattered evidence that such arrangements have existed amongst hospitals. For example, in a survey of metropolitan hospital associations by Yett (1970), 14 of the 15 respondents reported having established successful ‘wagestandardization’ programs and the 15th asked for information about establishing one. Devine (1969) provides similar evidence on hospital collusion over wages in Los Angeles in the 1960s.

More recently, in 2006 nursing groups filed class action lawsuits against hospital chains in several large cities across the US (Greenhouse, 2006). These lawsuits alleged that the hospitals shared information about the wages of competitors for the purpose of keeping RN wages low (Miles, 2007), in violation of antitrust laws. An interesting feature of all of this evidence is that the collusion apparently took place in large metropolitan areas with many employers. In this light, the notion that the opportunity to collude is limited to those areas with high employer concentrations seems dubious. Indeed, the opportunity to share information on wages with competitors through consulting companies that conduct compensation surveys may enable a substantial degree of ‘arm’slength’ or tacit collusion.

Nurse Labor Supply

A common part of a priori arguments for monopsony in the nurse labor market is the notion that the market-level elasticity of LS for nurses is low due to high mobility costs. With few other hospital employers in an area, any job switching, particularly for RNs, would likely entail either relocating to a different area or switching to a different occupation. Yett argued both costs were substantial since (1) many nurses were married and their location decisions were likely constrained by their husbands’ careers and (2) ‘‘few other occupations for which nurse training provides any advantage pay competitive salaries’’ (Yett, 1970, p. 381), so it would be costly for a nurse to switch to another occupation. To support this claim, Yett cited the results of a survey of nurses that reported low mobility rates overall, and suggested only 4–8% of nurses reported changing jobs because they were dissatisfied with their pay. More recently, Shields (2004) reviews a range of studies of nurse LS conducted over the past four decades, and reports the overall conclusion that nurse (market level) LS is indeed quite unresponsive to wages.

An implication of monopsony first highlighted by Robinson (1933, p. 302) is that employers may be able to discriminate between different types of workers. In particular, if there are two groups of workers with different LS elasticities to the firm, the profit-maximizing employer will offer a lower wage to the group with less elastic supply. Robinson provided a theoretical example where a wage differential emerged between male and female workers assumed equally productive, but men were organized into a trade union and thus had perfectly elastic supply at the union negotiated wage rate. In the nurse labor market, this phenomenon is a potential explanation for the wage premium paid to temporary contract, or registry, nurses.

In general, however, it is not clear that nurses stand out from other workers in the sense of having markedly different LS elasticity. For example, motivated by the intuition of the Burdett and Mortensen (1998) search model outlined above, Hirsch and Schumacher (2005) calculate the fraction of new RN hires from nonemployment using Current Population Survey data for the years 1994 to 2002, and find that 41.8% of recruits come from nonemployment on average each year. Surprisingly, however, they find that the ratio is actually higher (51.2%) for a nonnursing control group (women with a college degree). Although this does not imply that the RN market is not monopsonistic, it does cast some doubt on whether the nursing market is distinctively so.

Other Features

The features of the nurse labor market described in Section Nurse Labor Supply help to explain why health labor markets are singled out disproportionately in discussions of monopsony. There are other empirical ‘puzzles’ that have been documented more broadly in the economy, however, that some have argued are more naturally explained by monopsony models than by a model with a perfectly competitive labor market (Bhaskar et al., 2002; Manning, 2003). Without going into much detail, it is noted in passing that many of these ‘puzzles’ are characteristic of the nurse labor market as well.

One hallmark of the competitive model is the ‘law of one wage’ (Bhaskar et al., 2002, p. 156), or the prediction that similarly productive workers should all receive the same wage at jobs that are similar in their nonwage attributes. In nursing labor markets, wage differentials across employers are quite common. For example, in 2005 among 363 nursing homes in Los Angeles county, the average hourly wage level of RNs was US$28.2 (2005 dollars). But the firm at the 10th percentile of the firm-average wage distribution paid US$23.4 and the firm at the 90th percentile paid US$32.9, or 40% more. Such differentials are more pronounced for more skilled nurses, but are present for nurse aides as well. Among the same set of nursing homes, nurse aides made US$9.7 on average but the firm at the 90th percentile paid US$10.9 on average, or 25% more than the firm at the 10th percentile (US$8.7). (These data are taken from Matsudaira (2010), and are described in more detail there. Note that a limitation is that they represent average wages paid to a particular occupation by a firm. It is likely that this understates the degree of wage dispersion, though part of the differentials will reflect differences in composition among workers across firms, e.g. in experience. Also see Machin and Manning (2004) for an interesting and more detailed study of wage dispersion among nursing home workers in the UK.)

Some economists have argued that wage dispersion might reflect differences in worker productivity or compensating differentials for nonwage aspects of the jobs at different firms. But another piece of evidence argues against such explanations: turnover is negatively related to wage levels. Using data on the same set of Los Angeles nursing homes from 1981 to 2004, a regression of turnover rates for nurse aides on their average wage levels and a set of facility and year fixed effects suggests that raising hourly wages by $1 reduces turnover by approximately 7.4 percentage points (approximately 10%). If wage differences reflect unobserved productivity differences, there should be no reason for low wage workers to leave their jobs at higher frequency since they would not expect to be able to get the higher wage jobs. Similarly, differences driven by compensating differentials are inconsistent with the turnover result as switching from a low to a high wage job would not yield an expected utility gain.

Another interesting feature of labor markets that has challenged competitive theory is the fact that many employers seem to provide and pay for general human capital training to their workers. With perfect labor mobility, one might be skeptical that firms have an incentive to do this since they would be unlikely to recoup any investment in their workers’ human capital that is not firm-specific Becker (1993). Despite this, it appears common for hospitals to pay for general skills training for their nurses, consistent with the view that imperfections in the labor market allow firms to recoup part of their investment in their employees general skills (Acemoglu, 1997). For example, May et al. (2006) document that many hospitals in their survey offer in-house nurse training programs, or subsidize their staff’s training at nearby nursing schools. Benson (2011) provides a test of monopsony of sorts based on this reasoning, showing that hospitals with higher concentration ratios in their metropolitan area are more likely to subsidize training to RNs.

Empirical Studies Of Monopsony

What direct evidence is there about whether nurse labor markets are actually monopsonistic? Previous studies on this question can be grouped into two broad categories: (1) an early literature that attempts to determine whether there is a link between employment concentration and the level of nurse wages, and (2) a more recent and smaller set of papers attempting to directly estimate the facility level elasticity of LS for nurse employers. Each of these literatures are discussed in turn.

Concentration And Wages

The first serious empirical test of the hypothesis that nursing markets are monopsonistic was Hurd (1973). Using data from the 1960 Census, Hurd estimates the relationship between hospital employment concentration and median nurse earnings across the 100 largest Standard Metropolitan Service Areas (SMSAs). The regression model includes control variables for the cost of living, the percentage of nurse employment accounted for by hospitals, the percentage of hospital employment accounted for by federal hospitals and the percentage accounted for by state and local hospitals, and the percentage of nurses receiving earnings who worked for less than 50 weeks. Hurd finds that holding these other factors constant, there was a significant negative relationship between concentration, measured by the share of employment of the eight largest hospitals, and median nurse earnings. In auxiliary analyses using wage data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics for a subset of cities he finds a similar relationship, and interpreted his findings as supportive of the monopsony hypothesis.

Subsequent studies by Link and Landon (1975), Feldman and Scheffler (1982), and Robinson (1988) (Robinson (1988) tests the prediction that the employment of nurses will be relatively low in areas with higher hospital employment concentrations.) confirm Hurd’s findings, using hospital-level data and slightly different measures of firm concentration (e.g., a Herfindahl index based on hospitals’ share of total beds in a city). As emphasized above, however, a correlation between concentration and wages is only evidence of monopsony if other factors related to LS and demand are held constant across markets.

More recent studies, such as Adamache and Sloan (1982) and Hirsch and Schumacher (1995), suggest that the relationship between concentration and wages may not be robust to better controls for such factors, such as population density and the wages of alternative occupations. The best study in this literature is probably Hirsch and Schumacher (1995), who pursue a two-step strategy for testing the prediction that hospital concentration depresses wages. Using data from the 1985 to 1993 Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group (CPS-ORG) files, they first identify a control group of workers for each type of three nurse occupations (RNs, LPNs, and nurse aides) based on similarities in educational requirements. Then, for each occupation they estimate the relative wage gap between nurses and their respective control group separately for each of 252 geographic areas – including 202 metropolitan areas and 50 nonmetropolitan area state groups – controlling for worker characteristics and time effects. In a second-step regression, they then test whether hospital concentration and market size are correlated with the nursing wage differential and find no evidence that supports such a claim for any of the nurse occupations considered. (In a follow-up study, Hirsch and Schumacher (2005) use a similar design to see whether an alternative measure of monopsony power – the fraction of RN recruits from nonemployment – is correlated with wages across geographic areas. They find again no evidence for monopsony power for hospitals.)

The research design in Hirsch and Schumacher (1995) is clearly better than earlier studies in that measuring nursing wage differentials relative to a control group more effectively controls for market specific differences in demand and supply conditions that apparently confound earlier estimates. That said, the design relies heavily on the premise that nonnursing occupations are not subject to monopsony, or more accurately that variations in monopsony power in nonnursing labor markets is uncorrelated with variations in hospital concentration and market size. If monopsony is a more pervasive feature of labor markets for other occupations, then the approach may understate the wage-setting market power of hospitals.

Labor Supply To The Firm

As discussed in Section Models and Predictions, the key distinguishing feature of monopsony models relative to perfect competition is an upward sloping LS curve to individual firms. Despite its importance, only a handful of studies have attempted to credibly estimate this elasticity parameter. The reasons for this are readily apparent: the observed changes in wage and employment levels across firms are in general the result of changes to both supply and demand. So long as the supply curve is shifting, the observed equilibria cannot reliably be used to identify its slope. This is a well-known problem in economics dating back at least to Haavelmo (1943), but the solution of finding a ‘demand shifter’ to use as an instrumental variable for the observed quantities, tricky in the best of settings, is particularly difficult in this case. Since firm-level LS is of interest, any instrument must act differentially only on the labor demand of the specific firm in question so market wide phenomena are off the table.

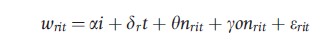

Sullivan (1989) was the first to make a serious attempt at estimating the firm-level elasticity of LS to individual hospitals using data from 1979 to 1985. He derived LS equations based on different assumptions about the nature of competition among firms in an oligopsonistic setting, and controls for hospital and region specific fixed-effects to estimate the (inverse) elasticity of supply. For example, assuming Nash equilibrium in employment levels his estimating equation is

where writ represents log wages for hospital i in region r at time t; nrit is the log number of nurses employed; and onrit the log of the sum of nurses employed at other hospitals. y represents the inverse elasticity of supply. The simultaneity problem is addressed by using the number of caseloads and average length of stay as instrumental variables for the number of nurses at hospitals, the notion being that these variables affect output demand and thus the derived demand for nurses but not necessarily nurse supply for a given hospital. Sullivan finds that the inverse elasticity of supply is approximately 0.79 (with standard error of 0.13) over a 1-year period and 0.26 (0.07) over a 3-year period and asserts this represents a significant amount of market power for hospitals. In a static model these elasticities can be used to compute the ‘markup’ of marginal product over wages using eqn [1], in this case implying wages are between 43% (for 1-year changes) and 21% (for 3-year changes) below marginal product. In a dynamic setting, however, this ‘rate of exploitation’ is a weighted average of short and long run elasticities where the weights are a function of a firm’s discount rate. Assuming a long run elasticity of zero, Boal and Ransom (1997, p. 105) suggest Sullivan’s estimates imply that wages might be set between 87% and 96% of marginal product. Using this logic, they characterize Sullivan’s results as being suggestive of only slight market power for hospitals but of course such a conclusion rests on the accuracy of its assumptions.

The validity of this instrumental variable has been questioned. Staiger et al. (2010) point out that Sullivan’s sample brackets a period when Medicare’s Prospective Payment System is introduced, and suggests that much of the variation in hospital days over the period was therefore endogenous as the transition presumably may have led to independent (downward) pressure on nurse wages. Manning (2003) suggests, alternatively, that caseloads might be related to population shocks, and thus might fail the exclusion restriction.

An instrumental variable strategy is also employed by Staiger et al. (2010) who use legislated wage changes in Veteran’s Affairs (VA) hospitals to identify the firm-level LS elasticity of RNs. Similar to the analysis in Sullivan (1989), Staiger and his coauthors adopt an explicit model of oligopsony (based on Salop (1979)) where hospitals compete most intensively with hospitals in close proximity, leading to an estimating equation where employment depends on a hospital’s own offered wage but also the average wage at nearby hospitals. They demonstrate that VA wage changes affect the wage levels of RNs at nearby hospitals (up to 30 kms away), suggesting that hospitals do have the ability to set wages. Using gaps between the newly legislated wage and wages at the time of the legislation as instruments for wage changes, the estimated LS elasticity over a 2-year period ranges from approximately 0 to 0.2 with standard errors approximately 0.13 (or an inverse elasticity ranging from approximately 5 to infinity). Even using the upper bound of the 95% confidence interval from Staiger et al.’s estimates implies that the inverse elasticity of LS is at least 2, far from the 0 assumed by the theory of perfectly competitive labor markets.

Matsudaira (2010) attempts to estimate the degree of monopsony power for nursing home employers using a different strategy. In 2000, the state of California adopted minimum staffing regulations for nursing homes requiring them to employ a minimum number of nursing hours for each patient in residence. Depending on the gap between a home’s initial staffing level and the legislated threshold, this law created more or less pressure to hire additional nurses to comply. Thus, Matsudaira uses this measure of the staffing gap as an instrument for subsequent changes in nurse employment.

Despite finding that homes initially out of compliance with the staffing law did hire significantly more nurse aides than those already in compliance, there were no differences in wage changes of aides across these groups of firms suggesting a highly elastic firm-level LS curve (i.e., an inverse elasticity close to 0). Since homes complied with the law almost exclusively by hiring nurse aides, the LS elasticity estimates for more skilled nurses (RNs and LPNs) were not estimated.

The estimates in Matsudaira (2010) differ markedly from those in Sullivan (1989) and especially Staiger et al. (2010). This may reflect differences in the supply elasticities of different kinds of nurses – nurse aides do not have near as much occupation-specific human capital, and so may have a broader set of alternative employers and thus more elastic LS. Or, if factors such as ignorance about alternative wage offers are the primary source of labor market frictions and this ignorance affects all occupations similarly, then the results may well be in conflict. A third possibility raised by Manning (2011) is that none of the studies are accurately measuring the firm-level LS elasticity, and that the models of firm-level LS used in the literature reviewed here are overly simplistic. This point is returned to below.

Discussion

Overall, the evidence above presents a very mixed case on the empirical relevance of monopsony models for understanding the nurse labor market. On the one hand, as in other markets there seems to be strong prima facie arguments that the market is monopsonistic ranging from ‘smoking gun’ evidence of wage-fixing, to reports of vacancies, to wage dispersion and provision of training. On the other hand, formal tests of the implications of monopsony theory have yielded varied results. The best studies on the relationship between employment concentration and wage levels suggest there is no relationship, and direct estimates of firm-level LS elasticity have produced some estimates consistent with extremely inelastic LS, and some estimates consistent with perfectly elastic LS.

It would be suggested that part of the reason for these ambivalent results is the reliance on overly simplistic theoretical models to guide empirical work. As noted above, although some models predict that collusion is more likely in more concentrated industries, there seem to be many cases where employers have colluded to keep wages low even in large, fairly unconcentrated markets. (Relatedly, Levenstein and Suslow (2006) report that although most cartels that have been studied in the product market have few members (with a median number of companies approximately 6 to 9), about one-third have more than 10 members with some having hundreds of members. They report that with cartels of many companies, industry associations often play a key role in coordination.) More work on the prevalence of collusive agreements on wages and competition for employees, and the effects of industry associations and wage-information sharing through compensation surveys would be useful, particularly given the recent legal actions taken by RNs alleging wagefixing by hospital chains in many large MS as in the US. It may well be that traditional measures of concentration are a poor proxy for the prevalence of collusion among employers to keep wage levels low in the nursing labor market. (Another interesting direction for future research is exploring the ways in which regulations restrict competition in the labor market. In a recent study, Kleiner and Park (2010) show evidence that state licensing rules restricting the work that can be done by dental hygienists have important effects on the earnings of hygienists and dentists. Licensing is obviously a pervasive feature of the health labor market, as are noncompete clauses among physicians. Exploring the consequences of such regulations for health care workers would be an interesting addition to the literature.)

Manning (2011) makes the point that if the firm-level LS function is not one-to-one with respect to wages, then the elasticities estimated in the literature may be incorrect. For example, if LS to the firm depends both on wages and recruitment expenditures (e.g., on advertising vacancies), then faced with a mandatory increase in employment it may be optimal for the firm to respond by increasing recruitment expenditures rather than by increasing wages. If such a model applied, the results of Matsudaira (2010) might overstate the LS elasticity to the firm, and conversely a design estimating the impact of a legislated wage increase on employment like Staiger et al. (2010) might understate the degree of elasticity. Other models with heterogeneity in worker quality or nonwage aspects of jobs can have similar implications. For instance, Matsudaira (2010) cautions that firms may respond to the mandate to hire more nurses by reducing their hiring standards with respect to worker quality at a given wage. If so, then the LS curve to the firm for nurses of a given quality may well be upward sloping even given his result that wages remain constant in firms that hire more nurse aides. Currie et al. (2005) test the predictions of a monopsony model in the context of examining the effects of hospital mergers on RN wages, and suggest that nurse effort (proxied in their context by nurse–patient staffing ratios) may be an important nonwage dimension that hospitals use to affect LS. They suggest that rather than suppressing wages, hospital mergers may lead to increased nurse effort for a given wage, a result consistent with the predictions of monopsony in their model. (The result is also consistent with a contracting model that they develop.)

The empirical literature on the importance of monopsony in the nurse labor market has yet to provide a conclusive answer. As suggested above, however, this is in part because our theoretical understanding of frictions in the labor market has evolved. Unfortunately it is difficult to formulate tests that would allow one to definitively reject monopsony or perfect competition under all theoretical formulations, and the tests that suggest themselves are hard to capture in the ‘real world.’ To wit, the thought experiment ‘‘what would happen if one employer was randomly forced in a market to increase its wage holding the wages of all competitors constant?’’ is easy to posit but near impossible to observe in the wild. Moreover, formulating direct tests of more general models of monopsony (Manning, 2006) present a challenge since many other determinants of LS are hard to observe at the firm level. In general, there are little data on worker quality, nonwage attributes of jobs, recruitment expenditures, and the other margins along which employers might adjust in response to (firm-specific) labor demand shocks. However, there may be relatively greater opportunities to advance a research agenda along these lines in the nurse labor market due to a long history of health management studies focused on understanding the determinants of nurse turnover and job satisfaction.

Acknowledgment

The author thanks Matthew Freedman for helpful comments on an earlier draft, and the National Science Foundation for financial support under grant SES-0850606.

References:

- Acemoglu, D. (1997). Training and innovation in an imperfect labour market. The Review of Economic Studies 64, 445–464.

- Acemoglu, D. and Pischke, J. S. (1999). Beyond becker: Training in imperfect labour markets. The Economic Journal 109, F112–F142.

- Adamache, K. W. and Sloan, F. A. (1982). Unions and hospitals: Some unresolved issues. Journal of Health Economics 1, 81–108.

- American Hospital Association (2010). The state of America’s hospitals – Taking the pulse. Available at: http://www.aha.org/research/policy/2010.shtml (accessed 26.07.13).

- Archibald, G. C. (1954). The factor gap and the level of wages. The Economic Record 30, 187–199.

- Arrow, K. and Capron, W. (1959). Dynamic shortages and price rises: The engineerscientist case. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 73, 292–308.

- Ashenfelter, O. C., Farber, H. and Ransom, M. R. (2010). Labor Market Monopsony. Journal of Labor Economics 28, 203–210.

- Becker, G. S. (1993). Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis with special reference to education, 3rd ed. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Benson, A. (2011). Firm-sponsored general education and mobility frictions: evidence from hospital sponsorship of nursing schools and faculty. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute for Technology. unpublished Mimeo.

- Bhaskar, V., Manning, A. and To, T. (2002). Oligopsony and monopsonistic competition in labor markets. Journal of Economic Perspectives 16, 155–174.

- Bhaskar, V. and To, T. (1999). Minimum wages for Ronald McDonald monopsonies: A theory of monopsonistic competition. Economic Journal 109, 190–203.

- Blank, D. M. and Stigler, G. J. (1957). The demand and supply of scientific personnel. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Boal, W. M. (2009). The effect of minimum salaries on employment of teachers: A test of the monopsony model. Southern Economic Journal 75, 611–638.

- Boal, W. M. and Ransom, M. R. (1997). Monopsony in the labor market. Journal of Economic Literature 35, 86–112.

- Buerhaus, P. I., Auerbach, D. I. and Staiger, D. O. (2009). The recent surge in nurse employment: Causes and implications. Health Affairs 28, w657–w668.

- Bunting, R. L. (1962). Employer concentration in local labor markets. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

- Burdett, K. and Mortensen, D. T. (1998). Wage differentials, employer size and unemployment. International Economic Review 39, 257–273.

- Card, D. and Krueger, A. B. (1995). Myth and measurement: The new economics of the minimum wage. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Currie, J., Farsi, M. and Macleod, W. B. (2005). Cut to the bone? Hospital takeovers and nurse employment contracts. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 58, 471–493.

- Devine, E. (1969). Manpower shortages in local government employment. The American Economic Review 59, 538–545.

- Falch, T. (2010). The elasticity of labor supply at the establishment level. Journal of Labor Economics 28, 237–266.

- Feldman, R. and Scheffler, R. (1982). The union impact on hospital wages and fringe benefits. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 35, 196–206.

- Greenhouse, S. (2006). Suit claims hospitals fixed nurses ‘pay. New York Times, NY, NY. June 21.

- Haavelmo, T. (1943). The statistical implications of a system of simultaneous equations. Econometrica 11(1), 1–12.

- Hirsch, B. T. and Schumacher, E. J. (1995). Monopsony power and relative wages in the labor market for nurses. Journal of Health Economics 14, 443–476.

- Hirsch, B. T. and Schumacher, E. J. (2005). Classic or new monopsony? Searching for evidence in nursing labor markets. Journal of Health Economics 24, 969–989.

- Hurd, R. W. (1973). Equilibrium vacancies in a labor market dominated by nonprofit firms: the ‘shortage’ of nurses. The Review of Economics and Statistics 55, 234–240.

- Kleiner, M. M., Park, K. W. (2010). Battles among licensed occupations: Analyzing government regulations on labor market outcomes for dentists and hygienists. National Bureau of Economics Research Working Paper. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Landon, J. H. and Baird, R. N. (1971). Monopsony in the market for public school teachers. American Economic Review 61(5), 966–971.

- Levenstein, M. and Suslow, V. (2006). What determines cartel success? Journal of Economic Literature 44, 43–95.

- Link, C. R. and Landon, J. H. (1975). Monopsony and union power in the market for nurses. Southern Economic Journal 41, 649–659.

- Machin, S. and Manning, A. (2004). A test of competitive labor market theory: The wage structure among care assistants in the South of England. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 57, 371–385.

- Manning, A. (2003). Monopsony in motion. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Manning, A. (2006). A generalised model of monopsony. The Economic Journal 116, 84–100.

- Manning, A. (2011). Imperfect competition in the labor market. Handbook of Labor Economics 4B, 973–1041.

- Matsudaira, J. D. (2010). Monopsony in the low-wage labor market? Evidence from minimum nurse staffing regulations. (in press).

- May, J. H., Bazzoli, G. J. and Gerland, A. M. (2006). Hospitals’ responses to nurse staffing shortages. Health Affairs 25, W316–W323.

- Mayo, D. G. (1996). Error and the growth of experimental knowledge. London: University of Chicago Press.

- Miles, J. (2007). The nursing shortage, wage-information sharing among competing hospitals, and the anti-trust laws: The nurse wages antitrust litigation. Houston Journal of Health Law and Policy 7, 305–378.

- Pauly, M. V. (1969). Discussion. American Economic Review 59, 565–567.

- Pigou, A. C. (1924). The economics of welfare, 2nd ed. London: MacMillan.

- Reynolds, L. G. (1946). The supply of labor to the firm. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 60, 390–411.

- Robinson, J. (1933). The economics of imperfect competition. London: MacMillan.

- Robinson, J. C. (1988). Market structure, employment, and skill mix in the hospital industry. Southern Economic Journal 55, 315–325.

- Rosen, S. (1970). Comment on the chronic ’shortage’ of nurses: A public policy dilemma. In: Herbert, E. K. and Helen, H. J. (eds.) Empirical Studies in Health Economics: Proceedings of the Second Conference on the Economics of Health, pp. 390–397. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press.

- Salop, S. C. (1979). Monopolistic competition with outside goods. Bell Journal of Economics 10, 141–156.

- Shields, M. (2004). Addressing nurse shortages: What can policy makers learn from the econometric evidence on nurse labour supply? The Economic Journal 114, F464–F498.

- Staiger, D., Spetz, J. and Phibbs, C. (2010). Is there monopsony in the labor market? Evidence from a natural experiment. Journal of Labor Economics 28, 211–236.

- Stigler, G. (1964). A theory of oligopoly. The Journal of Political Economy 72, 44–61.

- Sullivan, D. (1989). Monopsony power in the market for nurses. Journal of Law and Economics 32, S135–S178.

- Yett, D. E. (1970). The chronic ‘shortage’ of nurses: A public policy dilemma. In: Herbert, E. K. and Helen, H. J. (eds.) Empirical Studies in Health Economics: Proceedings of the Second Conference on the Economics of Health, pp. 357–389. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press.