Despite their common medical school training and their shared title of ‘physician,’ there are many differences between physicians who enter different fields of medical practice. The most obvious difference is the variation in knowledge set and patient population that comes with each specialty. For example, pediatricians take care of children, whereas geriatricians take care of the elderly, and the types of conditions and diseases treated by these two types of physicians are completely disparate. Even among doctors who treat patients of the same age, there can be vast differences, as seen, for example, between psychiatrists (who often use counseling to treat unseen diseases of the mind, emotion, and personality) and radiation oncologists (who, with a requisite knowledge of physics, use radiation therapy to treat cancerous tumors).

However, the differences across medical fields go beyond scope of practice. With different areas of specialization come a range of patient interactions; whereas gynecologists almost always have face-to-face interactions with their patients, anesthesiologists most frequently see unconscious patients, and pathologists and radiologists rarely (if ever) see their patients at all. Similarly, the practice settings where physicians in different specialties work are quite variable: a family practitioner typically works out of an office, a hospitalist works in hospital medical/surgical units, an intensivist works amidst the machinery of a critical care unit, and a surgeon works in the operating room. Along with these different settings and patients come different schedules and work hours. Although a dermatologist may have typical office hours (Monday through Friday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.), a surgeon will typically start much earlier (5 or 6 a.m.) and frequently run late into the evening, and emergency medicine physicians have to work nights and weekends to staff the emergency room 24 h a day, 365 days a year. Another difference across medical fields is the degree of specialization. Whereas a family doctor will treat patients of all ages and genders, and thus must be expected to recognize (and treat) a vast range of conditions and diseases, a neonatologist, cardiac electrophysiologist, or gastroenterologist who specializes in colonoscopy will focus on a relatively specific subset of patients and conditions. Along with varying degrees of specialization come different lengths of training programs. A general internal medicine physician can practice after 3 years of residency training, whereas a pediatric neurosurgeon requires a 7-year neurosurgery residency, followed by a pediatric neurosurgery fellowship of at least 1 year.

Another significant difference between medical specialties, and the focus of this article, is average income. For example, in the US, physicians who practice in the primary care specialties (e.g., general internal medicine, family practice, and pediatrics) earn substantially less than physicians in nonprimary care specialties (e.g., dermatology, radiology, and orthopedic surgery), with some higher-income specialty physicians earning more than three times as much as their primary care contemporaries. These income differences also exist in other developed countries. For example, orthopedic surgeons earn twice as much per year as primary care physicians in Australia and the UK, and more than 50% more in Canada, France, and Germany.

To provide a glimpse of the variety in physician specialty income in the US, data from several waves of the annual Physician Compensation and Production Survey between 1995 and 2010 have been used in this article. The survey was conducted by the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA), spanning more than 2300 medical organizations and multiple specialties. Specialty classifications have been used based on Modern Healthcare salary surveys and Sigsbee (2011).

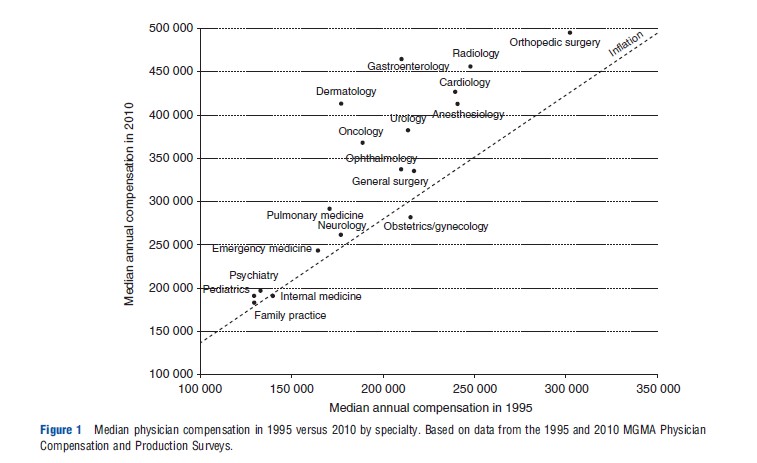

Figure 1 reports physicians’ median compensation in 1995 versus 2010 across 18 medical specialties. The dotted line represents the case where the 2010 compensation level equals the inflation-adjusted 1995 compensation level (using the consumer price index). Points below this line represent specialties for which median salary grew at a slower pace relative to inflation. For example, median compensation between 1995 and 2010 for Obstetrics and Gynecology grew 31.4% whereas inflation was 41.6%. Figure 1 highlights both the dispersion in compensation level within period as well as the widening of the gap over time. Even in 1995, the median compensation for anesthesiology, cardiology, radiology, and orthopedic surgery was nearly double the median compensation for family practice, internal medicine, pediatrics, and psychiatry. By 2010, these differences were more pronounced with orthopedic surgeons earning close to three times more than family practitioners. It is interesting to note that some specialties experienced greater growth than others. For example, the fastest growth in median compensation occurred for dermatology and gastroenterology.

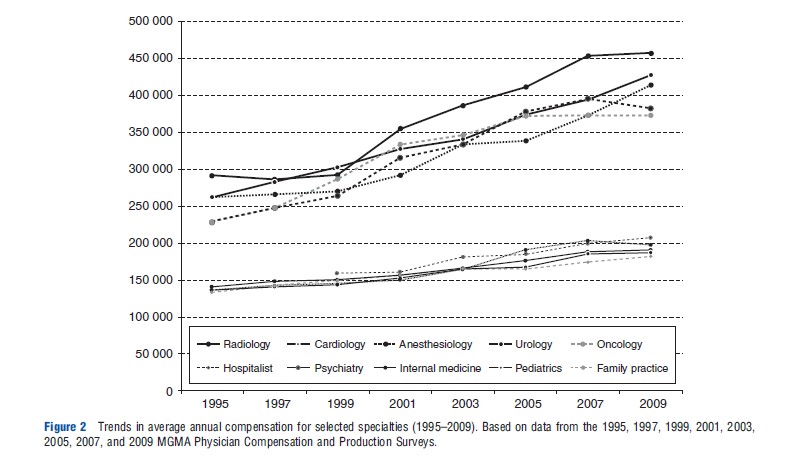

Figure 2 tracks average annual compensation for 10 specialties, for which data were available between 1995 and 2009. The income is plotted for five high-compensation specialties (radiology, anesthesiology, cardiology, urology, and oncology) and five low-compensation specialties (hospitalist (added to the survey in 1999), psychiatry, internal medicine, pediatrics, and family practice). Similar to Figure 1, both the difference at baseline (1995) and the difference in growth rates across highand low-compensation specialties are apparent.

Specialists in most other developed countries receive much higher income than their primary care counterparts, although there are a few exceptions. In 2004, specialists earned at least 50% more than primary care physicians in Canada, Austria, France, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands (in the US in that year, specialists earned 62% more than primary care physicians, on average) (Fujisawa and Lafortune, 2008). Primary care physicians in Japan earn more than specialists. This is probably because specialists are employed by hospitals, whereas primary care physicians tend to own their own practices, and physicians in Japan can provide a small number of hospital beds in their practice.

Aside from the potential discontent that this income gap may breed among different physicians, from a social or government policy perspective, this difference in expected income may have undesirable consequences. Research has shown that the US and Canadian medical students in general, when selecting their career specialty, are responsive to income differences. However, research has also shown that increased specialization leads to higher medical expenditures, without necessarily improving quality, mortality, satisfaction, or other important metrics of medical care. Thus, if specialists continue to have higher expected incomes than generalists or primary care physicians, the country’s healthcare system may continue down a path of higher cost, lower value care, and a shortage of generalist physicians.

Although the ongoing existence of this salary disparity is undisputed, the reasons for its existence are subject to continued investigation and debate. For many in the medical community, the explanation for this income gap is simple: the major government and private payers of medical services (e.g., National Health Service in the UK, Medicare in Canada, US Medicare, US Medicaid, and private health insurers) have decided to reimburse specialists at higher rates than primary care doctors. In 1992, Medicare adopted the resource-based relative value scale system for the US, which is designed to set reimbursement rates according to the relative value of and resource requirements of different services, and most major insurers have followed suit. This payment system generally reimburses specialists at much higher rates, even for patient visits of comparable duration (Bodenheimber et al., 2007). The relative value units used by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services in the US to label each type of physician visit and procedure are updated periodically, under the recommendation of the Relative Value Scale Update Committee, which is dominated by specialty (i.e., nonprimary care) physicians, who make up 85% of its voting members.

Although it may be true that reimbursement rates for physicians are set exogenously by payers, it is not clear how such price setting would establish a persistent income gap across physician specialties. As mentioned two paragraphs above, studies have shown that expected income has a strong influence on specialty physician labor supply. If this is true and if there were no major differences between medical specialties aside from their expected income, one would expect all medical students to choose specialties with higher expected incomes (e.g., radiology, orthopedic surgery, anesthesiology, and cardiology), leading to a massive shortage of physicians in specialties with lower expected incomes (e.g., general internal medicine, family practice, psychiatry, and pediatrics). A large enough shortage would increase the demand for physicians in primary care and other low-paying specialties, which would eventually lead health insurers to offer increased income to attract medical students to these specialties, ultimately equalizing the expected incomes of different physician specialties. However, in reality, although there is a perceived shortage of primary care physicians, there is an enduring disparity in physician incomes across specialties, indicating that there are underlying causes or forces preventing the equilibration of expected income for physicians.

Two potentially different phenomena are required for this physician income gap to emerge and persist. First, there must be factors that cause medical students to sort into different medical fields, despite the difference in expected income. Second, there must be a reason (or reasons) that the income gap across specialties is allowed to continue and expand. That is, there must be some factors preventing prices from clearing the physician labor market. This article considers these two elements as different possible explanations and their supporting evidence for the observed income gap are evaluated.

Potential Explanations For The Income Gap

As evident from Figure 1, the income gap between different physician specialties has been persistent and has widened over time. However, the reason that this gap exists and persists is less obvious and is subject to continued debate and research. In reviewing the different hypotheses that attempt to explain the persistent income gap, this article will consider both mechanisms by which physicians sort themselves into different specialties independent of income (i.e., the reason the income gap is established) and also mechanisms that limit physicians’ ability to concentrate in the highest paying specialties (i.e., the reason the income gap is maintained). The conclusion is that although individual preference can help explain why incomes differ across specialties to begin with, the most important reason why these differences persist and have grown over time is that barriers prevent medical students from entering high-income specialties. Because physicians who are already in a specialty largely control the number of students who are allowed to enter that specialty, this raises the possibility that certain specialties are behaving as a cartel.

Preference And Compensating Differentials

Aside from expected income, there are many other differences across medical specialties, including scope of practice, level of patient interaction, and regularity of working hours. Given this variety across medical fields, one might expect that a student’s choice of medical specialty will be multifactorial and will depend on more than just expected income. The idea that job features and amenities may compensate for lower income may provide a possible explanation behind the physician salary gap and its persistence. If preference for specialty choice are motivated by nonincome-related factors because individuals place less importance on expected income and more importance on, for example, the scientific content of their field, then some physicians will knowingly and purposefully choose lower-paying specialties, all in accordance with their individual valuation of other nonmonetary dimensions of the specialty.

In support of this hypothesis, many researchers have examined the influence of personality and personal preference on medical students’ choice of career specialty. Many studies have found associations between different personality types and specific medical fields. As an example, research has shown that the traits of ‘rule-consciousness’ and ‘tough-mindedness’ predicted differences between physicians in general surgery and family practitioners (Borges, 2001). Furthermore, other studies have found that predictability of working hours and lifestyle are key factors driving medical students’ choice of career specialty. For example, although pediatricians are paid less than trauma surgeons on average, it is often the difference in schedule structure (where general pediatricians work standard business hours that may extend into the evening as patient visits run over, whereas trauma surgeons work nights and weekends, but only in shifts with a well-defined beginning and end) that motivates students’ selection of one specialty over the other. Similarly, one might expect that a student who is passionate about treating children would choose to be a pediatrician, even though (as the student knows) most pediatric specialists are paid notably less than adult specialists covering the same area of expertise (e.g., cardiology, neurology, intensive care, etc.).

Other factors that vary across specialties and individual preference include specialties’ level of intellectual content, number of challenging diagnostic problems, availability of research opportunities, likelihood (and severity) of malpractice litigation, and prestige relative to other specialties. Indeed, research has shown each of these different factors can play important roles in shaping medical students’ choice of career specialty. It is important to note that not only is it possible for students to have different preference for any given career attribute (e.g., one student may prefer a field that is diagnostically challenging, whereas another student may prefer a field that is diagnostically simpler) but it is also likely that students assign different degrees of importance to different attributes (e.g., predictable working hours is very important to some students, whereas other students’ top priority is working in a specialty with more research opportunities). When considering all these different factors and how they might influence physician specialty selection, it is not surprising that differences in specialty income may be allowed to exist and persist. Certain specialties must have nonmonetary attributes that appeal to a large percentage of medical students, and this appeal has persisted (and perhaps grown) over time.

Ability Differences

In addition to preference, another individual characteristic that varies between people and might explain the income disparity is ability, although it does not appear to play a strong role in explaining income differences for physicians. Although the admission process for medical school is rigorous and extremely selective, medical students still vary in ability. Here, ability may refer to IQ, memory (e.g., learning speed, and capacity), physical skills (e.g., dexterity and endurance), or personality type or temperament. Realizing the diversity that exists across medical specialties, one might hypothesize that some specialties require abilities that are relatively rare among medical students whereas other specialties require more common abilities. This article will assume that specialties that require greater ability (or more uncommon ability) are intrinsically more difficult or challenging, as it is not clear otherwise why they would demand greater skill or talent. As in many other professions, workers with the highest abilities have rare attributes, skills, or talents, which would demand a salary premium over other workers, so the difficult or challenging specialties will offer higher salaries to attract highability workers.

Another type of ability to consider is a physician’s capacity for dealing with risk. Owing to their patient population and scope of practice, some specialties require physicians to act in higher risk situations. For example, most would agree that the likelihood and severity of patient harm from a physician mistake is greater in the fields of neurosurgery, anesthesiology, or interventional cardiology than in family practice or sports medicine. Moreover, specialists often accept more responsibility and thus risk compared to generalists. For example, it is commonplace for a family practitioner or general pediatrician to refer the patient to a specialist or an expert. The specialist, on the contrary, often represents the ‘end of the line,’ so the ultimate task of diagnosing and treating the patient often falls on the specialist. In this position, the specialist accepts more responsibility and risk (if the diagnosis or treatment is incorrect), so one might expect this additional responsibility to justify a salary premium.

As with the case of personal preference, differences in individual ability can potentially explain both why students sort themselves into different medical specialties and why the income gap between specialties is able to endure. If the more challenging specialties (that require greater ability) pay more and all medical students prefer greater income, all students will prefer to work in the more difficult fields. However, if entrance into a specialty, which is typically dictated by acceptance to a residency program, is determined according to ability, then only the highly skilled or talented students will be able to work in the more difficult specialties. Given the demanding application and interview process that is required for admission to residency programs, which consider test scores, clinical evaluations, and letters of recommendation, there is clearly a process that prevents low-ability students from achieving positions in high-ability specialties, thus allowing persistence of the income disparity.

In the literature, theoretical economic work has supported this hypothesis that large income differences may reflect even relatively small differences in ability. Furthermore, research has shown that some medical specialists score higher than others in terms of, among other traits, intelligence and self-sufficiency. However, other works have found little evidence that differences in ability are responsible for the large gap in physician income (Bhattacharya, 2005).

The National Resident Matching Program and the Association of American Medical Colleges collect data on the medical students who match into different residency programs in the US, and these data indicate differences in ability between the students entering different specialties (NRMP and AAMC, 2009). For example, there are significant differences in scores on Step 1 of the US Medical Licensing Examination between some higher-paying specialties (plastic surgery, neurosurgery, dermatology, and radiology) and lower-paying specialties (family practice, pediatrics, psychiatry, and physical medicine). Of course, these data do not indicate a causal relationship, but nevertheless the association between higher-paying specialties and students with higher test scores (a measure of ability) is noteworthy.

This being said, it is not clear whether or not the specialties with higher incomes are actually more challenging or demanding of greater physician ability than specialties with lower incomes. For example, is ophthalmology or dermatology more challenging than emergency medicine or neurology? Without any evidence of this, it is not clear that differences in medical students’ or physicians’ abilities are the reason that different specialties have different expected incomes. As long as students all want to maximize income and all residency programs want to attract students with the highest level of ability, residency programs for high-paying specialties will be able to select the most skilled and talented students, regardless of the reason(s) that different specialties have different expected incomes.

Workload And Effort

A straightforward explanation for why physicians in some specialties have higher salaries is that their specialties may require greater labor input. Taking this logic to the extreme, it may be that all physicians are paid approximately the same hourly wage, but those who work longer hours accumulate a greater total income. Furthermore, the effect of hours worked on income might be even greater if the marginal value of time increases as the number of hours worked increases. That is, comparing a physician who works 60 h per week to a physician who works 40 h per week, one might expect that the wage for the marginal hour should be higher for the former, because leisure time is more valuable to someone who spends more time working. This hypothesis of increased income with increased workload, if true, would provide a mechanism for both physician sorting into different specialties and the maintenance of the income gap, based on individual preference for income and leisure. Given equivalent hourly rates, those physicians who choose to work longer hours (i.e., choose specialties that demand more time) are knowingly sacrificing leisure to receive higher pay, whereas those who place a higher value on leisure will willingly forego higher income.

Although this concept is intuitively plausible, it is not supported by evidence. In fact, it would be more likely that labor input is responsive to the hourly wage than vice versa. Put differently, exogenous variation in hourly wage across specialties would induce physicians with identical laborversus-leisure preference to vary in their labor supply. Thus, without the ability to verify the authors’ assumptions of physician preference, it cannot be determined if the income disparity results from variation in the value that different physicians place on their leisure (even with similar hourly wages), or from variation in hourly rates, which translates mechanically into an income gap even when physicians exhibit similar labor-versus-leisure preference. To this end, research has shown that the number of physicians choosing a specialty is more responsive to changes in the number of relative hours worked than to changes in relative income earned. However, regardless of the assumptions, studies have found that only a small fraction of the income gap can be attributed to differences in the number of hours worked, indicating that hourly rates are almost certainly not equivalent across specialties (Bhattacharya, 2005).

Length Of Training

Another hypothesis commonly believed to explain the income disparity across physician specialties is the difference in required training. The reasoning behind this belief is frequently offered as an explanation for why physicians, on average, compared to other professionals are among the best-paid members of most societies. Looking within medicine and comparing different types of physicians, specialists undergo more training than generalists, and additional years in residency and fellowship create potentially important opportunity costs for specialists (in terms of lost time and wages). Thus, the hypothesis states that specialists are paid more to compensate for the additional costs of their extended training. Without this increase in expected income, physicians would not be willing to incur the additional costs of training required for specialization. Therefore, if medical students have different time preference for income, with some unwilling to take on short-term costs of training for the long-term gain of increased future income, they will sort themselves into specialties with different expected incomes.

In support of this hypothesis, research has indicated that medical students tend to prefer specialties with shorter residency training programs. However, other studies have shown that a relatively small portion of the income gap between different physician specialties can be explained by differences in training time; that is, students’ choice of specialty is mostly unresponsive to expected length of training (Bhattacharya, 2005). Furthermore, although some specialties (e.g., gastroenterology) provide a favorable return to specialization, other specialties (e.g., rheumatology) actually provide an unfavorable return to specialization (e.g., compared to staying in general internal medicine). As another example, the postgraduate training requirements for geriatricians and dermatologists are typically equivalent, but the expected income of geriatricians is often less than half that of dermatologists.

Aside from direct costs of longer training, other short-term financial considerations may motivate students to choose a specialty with a shorter training requirement, even if it means lower expected long-term income. The majority of graduating medical students has extensive debt, mostly from accumulated loans for undergraduate and graduate education, and although such loans can be deferred while students are in school, when the students graduate and enter residency programs, they must begin repaying these loans. Given the amount of debt that some students have (more than US$200 000), the size of loan repayments can be substantial, causing significant financial stress during residency. Other than educational loans, some students might expect other large financial burdens during residency, for example, supporting a new or growing family. Furthermore, although facing mounting financial demands, young physicians may have decreased access to private financial markets, as they are no longer eligible for educational loans. Any combination of these reasons can make residency training a particularly stressful financial time for young doctors, and this predicted stress may motivate students to choose specialties that minimize the length of residency, allowing them to become a practicing physician sooner. (Even the lowest paying jobs for practicing doctors pay at least three to four times more than a resident’s salary.) However, most of the specialties with shorter residency programs have lower lifetime expected incomes than the specialties with longer residency training, so students who choose shorter residencies are typically choosing lower long-term expected salaries. Thus, differences in specialty length of training combined with debt and short-term financial considerations may explain why some students choose lower-income specialties and why the physician specialty income gap continues to exist. Furthermore, other work has shown that not only just the amount of student debt but also the type of debt (e.g., subsidized vs. unsubsidized loans) is a significant variable in students’ choice of specialty.

Even for those medical students who are not carrying student debt or expecting increased financial stress during residency, there may be other motivations to choose a specialty with shorter residency training. For example, students might have very different future discount rates. Whether for financial reasons or otherwise, one could imagine students placing greater importance or value on the upcoming 5–10 years than on the more distant future; that is, a student might drastically discount all considerations that are more than 5–10 years away. In this time horizon, a medical specialty with a shorter residency program might appear more ideal than other specialties. For example, over the first 10 years of postgraduation, a student who enters family practice (3 years of residency) can expect to earn more than a student who pursues a career in surgery (more than 7 years of residency) because the income of the family practitioner will be much higher than that of a surgery resident. Thus, heterogeneity in time preference and subjective discount rates may help explain why income-maximizing students choose specialties with very different lifetime expected incomes.

Although most of the literature has explored variation in the length of formal training across specialties as a potential explanation for the income gap, no attention has been given to aspects of on-the-job training across specialties. Surgical and procedural specialists have to keep up with changing equipment, technology, and procedures and are required to invest considerable amount of time in order to do so. Therefore, an argument could be made that physicians in more dynamic fields require a premium for keeping up with the latest technologies and procedures. Nevertheless, it could be argued that generalists and nonprocedural specialists have just as many journals to read and new guidelines to keep up with. Moreover, most states necessitate continuing medical education (CME), but do not make distinctions across specialties; hence, specialists do not have to perform more CME than generalists.

Variation In Training Focus Across Medical Schools

Despite the theories and supporting studies that connect student debt to medical specialty choice, other researchers have shown that medical students entering primary care fields do not have significantly more (or less) debt than students entering nonprimary care fields. A medical student’s choice of career specialty is a complicated, multifactorial decision. Not only is that decision influenced by the interplay of personal preference and specialty characteristics but also the type of environment in which medical students are educated may also shape their choice of specialty. Medical schools can be viewed as producers of medical students, and although there is some standardization across medical schools, there can be substantial variation in the inputs that schools supply to this production process. Inputs in the medical student education process for any given medical specialty include, among other factors, preclinical curriculum, clinical rotation requirements, availability of mentors, and the presence of a residency training program. Through the variable use of these different inputs, some schools will produce more students who choose to pursue careers in primary care or other specialties. For example, the percentage of US graduating students who enter family practice varies (over a 10 year mean) from 1.7% to 34.9% depending on their medical school. Although the income gap across medical specialties may be established for exogenous reasons, the role played by medical schools may help explain how the income disparity is maintained. When students first enter medical school, they are less likely to exhibit strong preference toward a given medical specialty, because they may have limited understanding of the different fields and little awareness of income differentials across fields. Therefore, students are likely to select their medical school regardless of the specialty mix it typically produces, and hence to be sorted into specialties with different income profiles.

Research has verified that medical schools do influence students’ choices of career specialties. For example, the differential production of generalists versus specialists has been examined by studies that characterize the population of students who choose to enter family medicine residences. Supporting the hypothesis that medical schools may have different ‘production functions’ for medical students, research has shown that students from publicly funded schools are more likely to choose family medicine than students from privately funded medical schools. In some years, although some medical schools (including Johns Hopkins University, New York University, and Washington University in St. Louis) had no graduates who pursued careers in family medicine, at other schools (including University of Arkansas, the Medical College of Georgia, and University of Minnesota) greater than 22% of graduates entered family medicine residencies.

Institutional Barriers To Entry

Bhattacharya (2005) examined the role of different factors in explaining the disparity in physician income across specialties, and finds that only approximately half of the increase in expected income from specialization can be attributed to differences in hours of work, length of training, and skill or ability. Although individual preference and their implications for career path selection may explain some of the income disparity, barriers that prevent medical students from entering higher-income specialties offer another plausible explanation.

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) is the organization responsible for accrediting residency programs in the US, and thus it determines how many residency positions are available for training new physicians. Regulation of medical education and training is common in most developed countries. For example, the Medical Council of India, the Korean Institute of Medical Education, the General Medical Council (UK), the Netherlands–Flemish Accreditation Organization, and the Japan University Accreditation Organization approve curricula and accredit medical schools in their respective countries.

Broadly speaking, the restricted number of residency positions is a substantial factor (if not the most important factor) limiting the number of physicians who can enter professional practice, but it also plays a role in determining the number of physicians in different specialties. The ACGME oversees and sets policies for Residency Review Committees (RRCs), which are specialty specific and tasked with reviewing and accrediting hospital residency programs in their target specialties. In this position, an RRC essentially has complete control over the flow of physicians into a specialty because medical students who attend programs that are not certified by the ACGME are not eligible to take the licensing exam, and thus not able to practice in the US (Nicholson, 2003). Therefore, incumbents in a specialty determine how many new physicians may be trained in that specialty, which in turn will influence future earnings in that specialty.

Thus, regardless of the reasons why expected incomes vary across medical fields, the constrained number of available residency positions for each specialty prevents all medical students from entering higher-paying specialties, thus allowing the income gap to be sustained. High-income specialties in the US tend to have more residents who are trying to enter than there are positions available. For example, between 1991 and 2009, the ratio of the number of medical students who were trying to enter a specialty to the available number of first year residency positions exceeded 1.40 in orthopedic surgery in all but 1 year, and between 1997 and 2009 the ratio exceeded 1.60 in dermatology in all but 1 year. Barriers to entry exist in other countries as well. Medical school graduates in Greece often wait several years for a nonprimary care residency position opening.

Concluding Remarks

In developed countries, specialists, or nonprimary care physicians, earn considerably more than primary care physicians, and these income differences have persisted over time. This article reviews and assesses the support for different hypotheses regarding nonmonetary reasons why physicians may sort themselves into different specialties (i.e., the reason an income gap is established), and also hypotheses that help explain why the income gap persists.

Specialists can earn more than primary care physicians if the former medical fields require scarce abilities, have unattractive nonmonetary attributes (e.g., undesirable working environment), and require relatively long training. This will be particularly true if medical students have different time preference and debt levels. If these factors persist over time, such as medical students’ preference for the nonmonetary attributes of primary care, then the higher income of specialists relative to primary care physicians can also persist. The empirical support is strongest for the hypothesis that occupational attributes other than expected income do matter when medical students choose a specialty, and therefore do help explain income differences across specialties.

However, Bhattacharya (2005) finds that student preference explain approximately one-half of the specialty premium, with entry barriers to high-income specialties possibly explaining the balance. Thus, regardless of the reasons why expected incomes vary across medical fields to begin with, constraints on the number of available residency positions in high-income specialties prevent medical students from entering high-income specialties and driving down specialist income, and thus allow the income gap to persist. Because physicians who are already practicing in a specialty largely control the flow of new physicians into that specialty, this raises the question of whether certain high-income specialties are behaving as cartels. Making it easier for medical students to enter high-income specialties would reduce income differences across specialties.

References:

- Bhattacharya, J. (2005). Specialty selection and lifetime returns to specialization within medicine. Journal of Human Resources 40(1), 115–143.

- Bodenheimber, T., Berenson, R. A. and Rudolf, P. (2007). The primary care – specialty income gap: Why it matters. Annals of Internal Medicine 146(4), 301–306.

- Borges, N. J. (2001). Personality and medical specialty choice: Technique orientation versus people orientation. Journal of Vocational Behavior 58(1), 22–35.

- Fujisawa, R. and Lafortune, G. (2008). The remuneration of general practitioners and specialists in 14 OECD countries: What are the factors influencing

- variations across countries? OECD Health Working Papers No. 41, Paris, France: OECD.

- National Resident Matching Program (NRMP) and Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) (2009). Charting outcomes in the match: Characteristics of applicants who matched to their preferred specialty in the 2009 main residency match. Available at: http://www.nrmp.org/data/chartingoutcomes2009v3.pdf (accessed 16.05.11).

- Nicholson, S. (2003). Barriers to entering medical specialties. NBER Working Paper, #9649. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Sigsbee, B. (2011). The income gap: Specialties vs primary care or procedural vs nonprocedural specialties? Neurology 76(10), 923–926.

- http://www.nrmp.org/ National Resident Matching Program.

- http://www.oecd.org/health/health-systems/oecdhealthdata2012.htm