It is a commonplace to observe that the healthcare delivery system in the US is in crisis: costs are high and rising rapidly, the quality of care is inadequate along important dimensions, and the delivery system is rife with inefficiencies and waste. What is less commonly acknowledged is that many of the prominent strategies for reforming healthcare delivery systems are based on strong, largely untested beliefs about how organizations can best coordinate and motivate the physicians involved in patient care.

The crisis in the US system is especially severe and there is a large literature that discusses the US experience. For these reasons, this article focuses heavily on the US healthcare system. But many other countries are experiencing similar difficulties with their healthcare delivery systems and many of the issues and ideas discussed will have application beyond the confines of the US.

Health services researchers have long argued that a central problem with healthcare delivery in the US is fragmentation. Individual patients are frequently treated by numerous care providers who have only weak organizational ties with one another, resulting in poor information flows and inadequate care coordination. This fragmentation especially inhibits the close coordination between diverse providers that is required to manage costly chronic diseases and to prevent errors and missteps. The obvious fix, according to this view, is to induce physicians to join or construct more integrated care delivery systems. As a step in this direction, the Patient Protection Affordable Care Act of 2010 directs the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to create a voluntary program for Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs). This program is designed to nudge the US healthcare system toward more integrated care delivery.

In contrast to the health services research community, many economists have argued that the fundamental problem with the delivery system is poor incentives, primarily physician incentives. From this perspective, the continuing dominance of fee-for-service payment systems and flawed payment rates within these systems create strong incentives for physicians to deliver high-cost services. Incentives to improve care quality are largely indirect and weak – patients presumably seek out higher quality physicians but have little ability to evaluate physician quality. Expensive and inefficient practice styles are further supported by overly generous insurance coverage, a consequence of tax breaks for employer-based coverage and the widespread use of supplemental Medicare coverage.

The result is a bloated system where neither physicians nor patients are held directly accountable for the financial consequences of their care decisions. The obvious fix, according to this view, is to get incentives right by reforming payment systems and tax policy. Thus ACOs are encouraged to adopt new payment systems that, in principal, reward physicians for adopting practice styles that reduce costs and improve quality. At the heart of these payment reform proposals is an economic theory of how best to motivate physicians using material incentives.

This article presents an overview of organizational economics as it applies to physician practices. The first section, A Descriptive Overview, offers a brief descriptive overview of the structure of physician practices. Our point will be that the long-anticipated triumph of integrated care delivery has largely gone unrealized. Although fewer physicians are working in solo practices than in the past, self-employed physicians in small group practices remain the industry norm. Integration of physicians’ business functions has increased through a variety of cross-group and group-hospital affiliations, but integration of clinical activities has lagged. In the next section, Agency and Pay for Performance, the problem of pay for performance from the perspective of principal agent (PA) models is discussed. Building on these models, the next two sections take up the organizational economics of integrated care. The section Professional Autonomy versus Integration examines the professional norms of autonomy and other factors that complicate effective integration between hospitals and physicians. The section Coordination, Specialization and Innovation, considers how medical specialization affects coordination across providers. Finally the section Prospects for Accountable Care Organizations considers how the problems of motivation and coordination play out in ACOs.

A Descriptive Overview

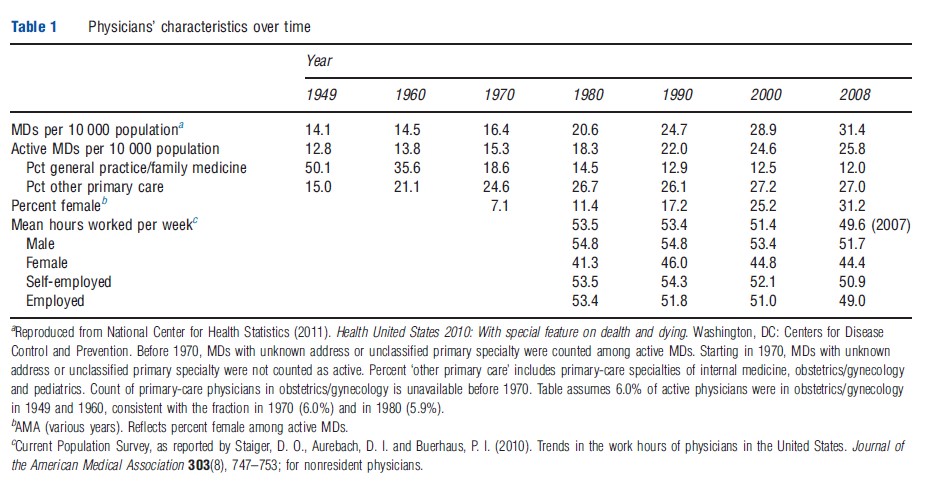

The physician workforce has evolved overtime in both size and composition. In the mid-twentieth century, there were approximately 14 physicians per 10 000 persons in the US, almost half of whom practiced general primary care (Table 1). In response to concerns about an impending physician shortage, the Kennedy and Johnson administrations successfully championed legislation subsidizing medical schools, doubling the number of medical school graduates from 1965 to 1980, and eventually doubling the physician-to-population ratio from 1970 to 2000. Despite a subsequent stabilization of medical school graduation rates, entry into the medical profession continued to modestly outpace population growth largely through an increase in international medical graduates, who now comprise a quarter of active physicians.

As medical knowledge and technology grew, the share of general practitioners in the medical profession declined more than 60% between 1949 and 1970, at which time fewer than 20% of active physicians practiced general primary care. The share of general practitioners continued its steep decline through the 1980s, though the decline was partially offset by growing shares of physicians practicing in specialties that typically involve primary-care services, i.e., pediatrics, obstetrics/gynecology, and internal medicine. Since 1990, the share of primary-care physicians (general practitioners plus primary-care specialties) has largely stabilized at 39% of all active physicians. Although the physician–population ratio in the US is similar to that in other developed countries, its share of primary-care physicians is substantially lower and this has been cited by numerous health policy experts as an important deficiency in the US healthcare delivery system.

The trend toward an increasing concentration of medical specialists has been accompanied by an increasing ‘feminization’ of the physician workforce and, more recently, by a decline in the labor supply of individual physicians. Historically, the medical profession was overwhelmingly dominated by male physicians. In 1970, approximately 7% of active physicians were women but the share of female physicians has grown consistently since then, reaching 31% by 2008. Coinciding with this change has been a decline in the number of hours physicians work each week, especially since the mid-1990s. Thus, although active physicians per capita increased 17% since 1990, physician work hours per capita increased less than 7%.

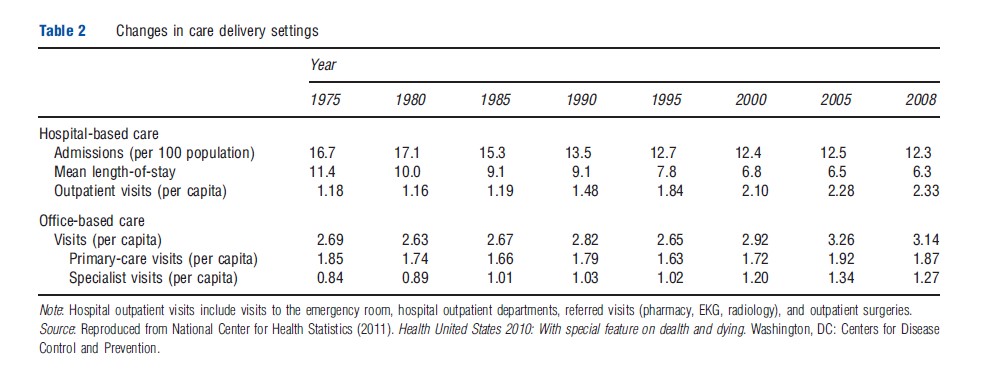

Table 2 documents trends in care delivery settings. Chief among these is a dramatic decrease in the amount of inpatient care provided. Since 1975, hospital admission rates have declined approximately 25%, whereas the length of hospital stays fell by almost one-half, representing a substantial decline in the amount of care physicians provide on an inpatient basis. In contrast, hospital-based outpatient care increased dramatically over this time, driven in part by a steep rise in outpatient surgeries. Meanwhile, the per capita rate of office based visits increased 17% since 1975, but this aggregate figure combines two very different trends. The rate of primarycare visits was relatively flat over this period, consistent with relative stability in the (per capita) number of primary-care physicians, whereas per capita office-based visits to specialists increased by more than 50%.

Thus a twofold story emerges from Table 2. First, physicians spend less time ‘making rounds’ and performing procedures in an inpatient setting than they did in the past, decreasing the dependence of physicians on hospitals as the setting for delivering services. Second, the decrease in inpatient care has coincided with a dramatic increase in ambulatory care delivered by medical specialists.

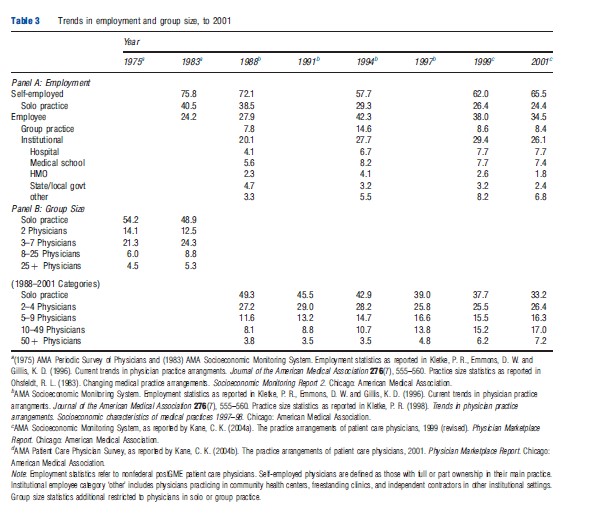

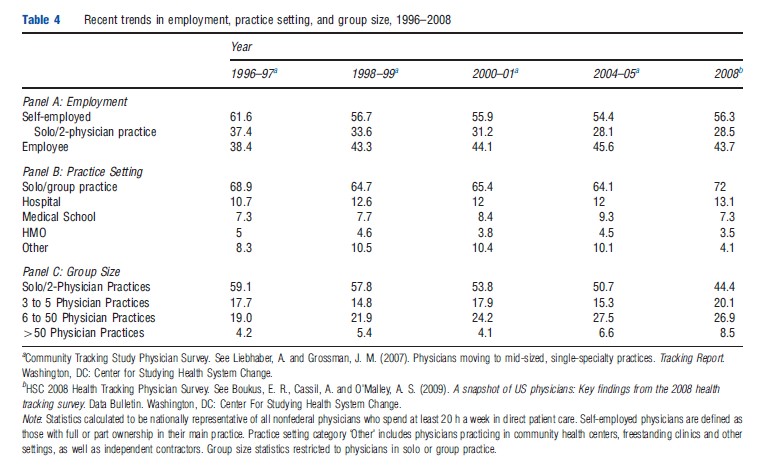

Tables 3 and 4 document how physician employment and practice arrangements have evolved over time. The results in Table 3 report statistics derived from a series of physician surveys conducted by the American Medical Association (AMA) – the Periodic Survey of Physicians (1975), the Socioeconomic Monitoring Study (1983–99), and the Patient Care Physician Survey (2001) – through 2001. More recent trends are documented in Table 4 drawing on data collected by the Center for Studying Health Systems Change (HSC) – four waves of data from the Community Tracking Study (CTS) Physician Survey and the HSC 2008 Health Tracking Physician Survey. Caution is always warranted in evaluating trends across different surveys. A special concern in this case is the sampling methodology of the CTS Physician Survey, which focused on 60 communities in the US. All statistics are weighted to be nationally representative, but trends in these communities may have differed from those in other areas, which could confound some of the cross-study patterns we observe. Nonetheless, these results allow us to draw a number of conclusions.

Physician self-employment has declined, but remains the norm: for much of US history the prototypical physician was self-employed and in solo practice. Even as recently as 1983, more than 40% of physicians fit this model but its numbers have been declining. By 2001, fewer than 25% of physicians were self-employed in solo practices. Overall rates of physician self-employment largely track the decline in solo practitioners, falling from 76% in 1983, to approximately 64% in 2000 (in AMA data), to less than 56% in 2008 (HSC data). In the CTS data, self-employment rates were somewhat lower than in AMA data, but a similar modest decline in self-employment rates is observed.

Institutional employment increased, but then appears to have stabilized (probably): the AMA data indicate that that the share of physicians working as employees of institutions (e.g., hospitals, medical schools, HMOs, etc.) grew from 20% to 28% from 1988 to 1994 – during the ascent of managed care – and then was fairly stable to 2001. The HSC data similarly find that approximately 28% of physicians were employees of institutions in 2008, suggesting little change over the last decade. The CTS data tell a somewhat conflicting story over the decade from 1996 to 2005, with rates of institutional employment seeming to increase from 31% to 36%. Given the nature of the CTS sampling methodology, one is inclined to believe this trend may not be representative of the nation as a whole, and that national rates of institutional employment have probably stabilized at a level less than 30%. It is likely, however, that local healthcare markets are quite heterogeneous in this regard.

Practice groups have gotten larger, but small practices remain the norm: health-system analysts have been predicting the demise of solo and small group practices for decades. Based on AMA data, it appears that a majority of noninstitutional physicians were in solo practice in 1975, declining to a third by 2001. Meanwhile, the share of employment in physician groups with more than 10 physicians grew from 12% to 19% between 1988 and 2001. The CTS data indicate that the share of noninstitutional physicians in solo or two-physician practices declined from 59% in 1996–97 to 51% in 2004–05, whereas the share in groups with six or more physicians increased from 23% to 34%. The historic record, then, is one of decreasing shares of physicians in the very smallest practices, and increasing shares in larger groups. Despite this, however, small groups remain a common feature of the physician labor market. In 2008, 65% of noninstitutional physicians were in practices with five or fewer physicians, accounting for 46% of the physician workforce overall.

Practice size and the prevalence of physician institutional employment (in hospitals and staff-model HMOs) provide an incomplete picture of the extent that individual physicians coordinate activities with one another and with other providers in the healthcare system. Over the last few decades, physician groups have increasingly joined a variety of cross group and group-hospital organizations intended to facilitate the collective goals of their participants.

Independent practice associations (IPAs) have emerged to provide solo and small group practices many of the benefits associated with larger group practice – economies of scale in insurance contract negotiations, contract oversight, and other administrative functions – while allowing participating physicians greater autonomy over their individual practices. According to the Managed Care Information Center, there are currently approximately 500 IPAs with approximately 264 000 participating physicians, which equates to approximately 55% of the active physicians in group practice.

A variety of organizations have emerged linking physicians and hospitals, with the goal of integrating service delivery and financing. The most common of these, physician-hospital organizations (PHOs), represent joint ventures between hospitals and private physicians to negotiate and manage insurance contracts. PHOs also frequently operate clinics, employ physicians and staff, and acquire medical practices. Some have established their own insurance products. At the apex of managed care in the mid-1990s, nearly a third of hospitals had one or more PHOs. The fraction has subsequently declined, falling to 13.4% by 2008.

A third type of organization, known as management service organizations (MSOs), are organizations owned by physician groups, by physician-hospital ventures, or by investors in conjunction with physicians. MSOs generally exist to provide practice management and administrative support, thus relieving practices of nonmedical business functions. In some cases, MSOs acquire the facilities and equipment of their client physicians which they then lease back to the physicians.

The widespread existence of such organizations can give the impression that physicians, even those in small practice, are often tightly aligned with one another and frequently integrated with hospitals in their geographic area. However, closer inspection suggests a more nuanced story. The rise of cross-group and group-hospital organizations was largely due to the market pressures imposed by managed care organizations (MCOs). Consolidating business functions allowed groups to achieve economies of scale in nonmedical activities and, more importantly, increased the clout of providers in contract negotiations. These organizations, however, were largely unsuccessful at integrating clinical activities across participating providers. As managed care backed away from capitated contracts, the impetus to integrate clinical activities largely faded.

Agency And Pay For Performance

Physicians know more than patients or insurers about the set of effective treatment options available for an individual with a specific condition. A patient’s own physician knows better than other physicians the specifics of the patient’s clinical and personal situation. Specialists, with their advanced training and narrow focus on a small set of clinical issues, have a better understanding of treatment options in their specialty than the primary-care providers who refer patients to them. Each of these informational asymmetries creates an agency problem, i.e., a situation in which well-informed physicians recommend or implement courses of action that benefit the well-informed physician at the expense of patients, payers, and other less well-informed parties.

One way to resolve information asymmetries is to design incentive contracts that motivate the best informed agent to ‘do the right thing.’ Economics offers a well-developed theory for tackling these incentive design problems, the PA model. The canonical PA model considers how a principal might structure incentives to elicit optimal behavior from better informed agents whose interests do not completely conform to the interests of the principal. The principal conditions pay on observed outcomes and the actions taken by the agent reflect the influence of these incentives. The starting point for the vast literature on PA models is a remarkable and quite general result: it is possible to implement a reward structure that can elicit efficient behavior on the part of the agent even when agents are entirely self-interested and even when performance measures are noisy and imperfect.

On the basis of this fundamental result, one might expect that the economist’s prescription for efficient healthcare delivery would be widespread use of pay for performance contracts. Unfortunately economic theory does not support such a simple policy prescription. The qualifications on the fundamental PA result are almost as far reaching as the result itself.

The first qualification has to do with the basic statistical properties of performance measures. Clinical outcomes are often influenced by some unknown combination of good actions (taken by the healthcare provider and/or the patient) and good luck. Because of the great diversity of possible medical conditions a patient can manifest and the limited number of patients in a physician’s panel of patients, it is not at all clear that an individual physician’s practice offers enough observations to reliably distinguish good luck from good medical practice.

Noise in performance measures becomes even more important when agents are risk averse. To see this, consider a setting in which physicians operate under a contract that rewards them for coming in under a threshold level of costs for their entire panel of patients. If costs vary substantially in a year due to actions outside of a physician’s control, then large payouts for coming in under target add a considerable component of randomness to a physician’s compensation. For risk-averse physicians, the increase in the variability of payments that result from incentive pay imposes a real cost. To make matters worse for incentive design, income variability rises with the intensity of the incentive. As a practical matter, insurers or HMOs that ignore the cost of this increased risk when implementing pay for performance will find they will need to pay more to attract physicians to their networks.

The problems posed by the low statistical power of clinical performance measures and the risk aversion of physicians can be mitigated by pooling information across many physicians. From an economic perspective, pooling or averaging performance measures is problematic because it makes agency problems worse. The larger the physician panels across which outcomes are measured, the less will be the effect of an individual physician’s actions on group outcomes. The phenomenon of group incentives weakening as the size of the group increases is well understood in the economics literature where it is often referred to as the ‘free-riding’ problem.

The relevance of free-riding problems is evident when one looks at the pay practices of physicians groups. Physicians who work in group practices often share revenues among themselves. Revenue sharing has the appeal of allowing physicians to buffer variations in income (doctor A’s extra income in a good year will help offset doctor B’s poor income in a down year), but this insurance comes at the cost of weakening incentives. If revenues are equally shared, a doctor in a three person group keeps one-third of each dollar he or she earns. Incentives weaken as the size of the group grows: a doctor in a five-person group keeps one-fifth of the marginal dollar in revenues they earn and so on.

If it is costly or difficult to use incentives to resolve agency problems with meaningful pay for performance systems, organizations might find it profitable to reduce the need for incentives by seeking out physicians who have their principal’s interests at heart. Consider a hypothetical physician who is committed to providing patients with the level of care the patient would choose for themselves if they knew as much as the physician knew and if the marginal cost of care were zero. Finding physicians with such ‘altruistic’ preference may not be as hard as it seems. Many aspects of medical education can be understood as efforts to inculcate this attitude into young physicians. It might appear that having physicians with such pro-social, intrinsic motives eliminates the most important agency problem facing doctors: the problem of ensuring that physicians act in the interests of their insured patients. But physicians face more than one agency problem and it is unlikely that the sort of intrinsic motives just described would resolve the agency problem for the insurers and MCOs that have the responsibility of paying for care. Indeed, if insurance contracts were such that the patients themselves had to pay the direct cost of their care, they also might prefer a physician whose internal values moved them to balance the marginal benefit of care against its marginal cost.

A deeper, but more speculative, limitation on the use of intrinsic motives to resolve agency problems is that these preference may not coexist easily with the use of material incentives. A growing body of theoretical and experimental evidence in economics and psychology points toward the provocative possibility that powerful extrinsic rewards can actually weaken the efficacy of such pro-social motives as altruism, reciprocity, intrinsic motivation, and a desire to uphold ethical norms. If true, this suggests that organizations that rely on a mix of material incentives and intrinsic motivators might be less efficient than organizations that rely solely on one or the other strategy to resolve agency issues.

To sum up, the economics literature suggests that incentives matter, but that high-powered pay for performance schemes may be too blunt a tool for handling the many agency problems that raise the cost and reduce the quality of healthcare. This depressing conclusion is offset by some more recent results in the organizational economics literature suggesting that it may be possible to resolve agency issues with very low-powered incentives by employing physicians in integrated healthcare delivery organizations. It is to that issue that the authors now turn.

Professional Autonomy Versus Integration

Hospitals and physicians together deliver the bulk of medical services in the US, yet they are strangely divided from each other. Within hospitals, physician decisions are central to resource allocation and care processes, yet most physicians are quite independent of hospital management, working (as most still do) in small single-specialty groups that they own. Some physicians have ‘privileges’ at more than one hospital and many more split their time and attention between hospital inpatient care and their office-based practices. It is hard to think of another industry – outside of movie making and construction – that relies so heavily on independent contractors as key decision makers. In virtually every industry that, like hospitals, relies on the mass-production of goods or services, key decision makers are either employees of the enterprise or, much more rarely, its owners. Does this difference matter for the efficiency of the healthcare system? Organizational economics suggests that it might.

For hospitals, the great advantage of having physicians as employees rather than independent contractors is that the employment relationship offers the possibility of resolving agency issues without the distortions created by high-powered incentives. This feature of employment relationships has been most clearly analyzed in the context of multitask models, where agents have more critical tasks to perform than can be included in performance measures. High-powered incentives will, in this context, cause the agent to deliver too much of the metered tasks and not enough of the unmetered tasks. Employment relationships offer a straight-forward fix for these multitask problems because employers have the ability to tell employees the tasks included in their job. By restricting the range of tasks the employee can work on while at work, the employer reduces the opportunity cost of doing the tasks the employer favors. As a result, a small amount of incentive can have a large effect on performance with lower levels of distortion. Put slightly differently, employment relationships differ from market-based relationships in that firms can exert a high degree of influence on employee actions using very little pay for performance. The strength of these low powered incentives is increased when combined with other features of well-run organizations: the careful selection of new employees combined with their subsequent socialization into the goals and procedures of the enterprise. The effectiveness of the combination of appropriate job design, careful selection, socialization, and low-powered incentives is captured by the term of art used in the management literature, ‘high performance human resource systems.’

To see the power of weak incentives in the context of employment relationships imagine that a hospital wishes to improve the way in which surgical tools are sterilized and delivered to operating rooms – a surprisingly complicated process that involves surgeons, operating room nurses, hospital managers, and sterilization technicians. Suppose further that operational efficiency can be improved by reducing the number and variety of surgical tools available to surgeons but that negotiating this change involves meetings and consultations with surgeons. If surgeons are independent contractors paid per operation, any additional meeting takes time away from the next operation. Attending such a meeting then, is a very expensive task for the surgeon and the surgeon requires equally large benefits in order to be induced to participate. This incentive problem is made worse by the fact that the benefits to the independent surgeon of reducing the number of surgical tools in circulation are clearly less than the benefits accruing to the hospital as a whole, especially if the surgeon divides his operating time across a number of hospitals.

Contrast these incentives with those of a surgeon who is employed by a hospital and is paid on salary. In this setting, attending meetings and participating in improving the sterilization process is not nearly so costly to the surgeon because the opportunity cost of his time is relatively low. These incentives to participate are further strengthened by the relationships the physician builds with coworkers and also by the extent of tacit, firm-specific knowledge, acquired over the course of the employment relationship.

Low-powered incentives of the sort discussed can complement higher-powered incentives and may help explain the anomalous findings of the Physician Group Demonstration project, an experiment in pay for performance involving large provider groups. Allowing these groups to keep 80% of their savings (after the first 2% of savings) elicited only small and uneven cost reductions. Very little is known about why some physician groups succeeded and others failed to achieve savings. Free riding can, as seen, undermine the incentive effects of conventional pay for performance – but the low-power organizational incentives discussed in this section can easily ‘scale up’ for large organizations. It is possible that the variation observed in the demonstration project may be the result of unobserved variations in low-powered incentives that can augment under powered explicit pay for performance incentives.

Given their considerable advantages, why hospitals employing physicians and forming large, integrated care delivery systems are not seen? In most economic settings, the efficiency advantages of integrated systems should enable them to generate the resources to attract large numbers of physicians and members. What prevents this from happening? Surprisingly little attention has been devoted to this important issue. The studies that do address it tend to focus on three potential explanations: the nature of economic competition in healthcare, strategic complementarities between payment systems and healthcare delivery, and the sociology of the medical profession. Each of these in turn are considered.

Regarding economic competition, if payers are unable to measure and reward high value-added producers, then it may be that the enhanced efficiency of integrated systems will not translate into a sustainable competitive advantage. Medicare, the biggest single buyer of healthcare services, does not evaluate the benefits associated with new medical technologies when setting prices, and it is forbidden from using cost-effectiveness analysis and from selectively contracting with more efficient physician groups. Medicare regulatory boards charged with evaluating new technology are concerned primarily with whether new drugs or procedures offer positive benefits. Private insurance coverage is heavily influenced by Medicare coverage. In addition, private payers typically use Medicare prices as a reference point in bargaining, and contracts based on value creation are scarce. Indeed it may be that some employers who purchase insurance for employees are not interested in or capable of evaluating the quality of care their employees receive. The key challenge for the ‘failure of competition’ explanation for the absence of integrated systems is explaining why competition in healthcare is different than in other sectors where markets do appear able to assess and reward efficient organizational designs.

In contrast, the ‘strategic complementarities’ explanation for the scarcity of integrated health delivery organizations refers to a generic set of explanations for the failure of advanced production methods to defuse rapidly across industries. Indeed much of this work was originally inspired by the difficulties American manufacturers had in imitating and adopting more efficient ‘lean’ manufacturing techniques that originated in Japan and the difficulties firms had in realizing productivity gains from the revolution in information. Suppose that managers have identified two complementary innovations, A and B. Each innovation on its own produces a small benefit, but introducing A and B simultaneously yields a big improvement in productive efficiency. For concreteness suppose that innovation A involves redesigning job responsibilities in ways that tap the tacit information and problem solving abilities of front line employees to solve customer problems and that innovation B involves hiring more educated workers. Implementing either of these changes is not easy or inexpensive and so it is reasonable to expect firms to experiment with one or the other innovation rather than implementing them both simultaneously. Thus, a firm might try action A and be disappointed in the result and therefore not follow-up with step B, hiring a more highly educated work force. Similarly, firms might start with B, but not see much productivity gain because they did not implement step A and redesign job responsibilities in ways that allow the more educated workers to use their superior problem solving and communication skills. It is only when firms reorganize and reskill the workforce that the powerful complementarities between the two innovations are realized. Put differently, incremental experimentation might not reveal the full productivity benefits of complementary innovations and so the true value of innovations might not be discovered by managers.

If complementarities can impede innovation within one organization, it becomes even harder when the complementary innovations span multiple organizations, i.e., when innovations are what game theorists call strategic complements. According to this argument the full efficiency gains of integrated care delivery can only be realized under bundled prospective payment systems. But in communities with highly fragmented care delivery, it is hard to find providers who can carry the risks entailed by such payments. As a result, payers do not innovate away from the status quo fee-for-service payment system and there is little competitive advantage for providers to move out of their currently fragmented delivery organizations. One of the interesting implications of the ‘strategic complementarities’ explanation is that it offers a natural role for public policy. Specifically, the big public payers (Medicare and Medicaid) can force the issue by announcing that they will be moving toward a bundled prospective payment system that will benefit large integrated organizations. This is the intellectual basis for the ACO initiative discussed below.

The third explanation for the relative scarcity of integrated care delivery organizations concerns social norms. The simplest version of the social norms explanation is this: physicians value professional autonomy and do not want to be employed by anyone else. There is considerable historical evidence that physicians as a learned profession did and do value their autonomy. Unfortunately, this fact alone is not likely to support a satisfactory explanation for fragmented delivery systems. If fragmentation between physicians and hospitals was simply the result of a preference for ‘being your own boss,’ then one should observe that physicians working for integrated systems enjoy a significant wage premium to compensate them for the disutility of their status as employees. One is not aware of any study that documents such a pay differential.

More sophisticated models of social norms, however, offer a more promising line of investigation. In models with a more sociological flavor, agents compare their actions with a prescribed set of behaviors or with the actions of others in their reference group.

In a conventional microeconomic analysis, if a physician decides to work as an employee at a hospital, only the hospital and the physician are involved in the transaction. All else equal, if the hospital offers a pay differential that exceeds the value the physicians personally place on autonomy, the physicians will choose to abandon the autonomy of their independent practice and go to work as an employee of the hospital. Things work quite differently, however, when norms enter the picture. Norm violating transactions necessarily precipitate actions or changed perceptions (and loss of reputation) by third-party physicians who are not party to the transaction. The involvement of these third parties allows professional norms to persist even when the gains to individuals from violating norms are large relative to their preference for the norm. The involvement of third parties also suggests that stubbornly persistent norms may be greatly weakened by shocks that change the actions or perceptions of many physicians at once.

Just such a change is currently taking place in the medical profession. For most of the twentieth century, professional norms in medicine, law, and other learned professions were shaped by a labor force composed almost entirely of men, and most of these men had stay-at-home wives. In the 1970s, however, women began entering professions in large numbers and today they account for a significant proportion of the labor force in both medicine and law. For our purposes, the significance of this demographic transition is that these new entrants are likely to be influenced by a different set of norms than the male incumbents. Specifically, these women are often married to male professionals who work long hours and they are for this reason quite likely to have to balance norms of medical practice against family responsibilities. To the extent that employment in a hospital or other large integrated delivery organization enables physicians to have shorter and more predictable hours than working as an entrepreneur in a small practice, women might be drawn to these positions and this may have the effect of undermining the norm of professional autonomy that has played such an important historical role in the US healthcare delivery system.

Norms-based models of professions shift attention from a narrow focus on individual incentives to a broader view that also includes incentives for action governing the entire profession. From this perspective it is interesting to observe that in the early-twentieth century the AMA successfully lobbied for the introduction of ‘corporate practice of medicine’ laws that made it illegal for physicians to be employed by other organizations, especially hospitals. The legal impact of these laws has diminished overtime (as witnessed by the rise of professional hospitalists, an issue taken up below), but their influence is still observed in some states.

If physician professional norms are important for understanding the failure of physician-hospital integration in the US, then they might also be important for understanding other market outcomes in healthcare. Consider, for example, that MCOs compete for patients (who are the paying customers) and for physicians to participate in their network of providers. Patients cannot directly perceive quality and use as a proxy the number of physicians included in the managed care network. The MCOs compete for physicians by offering a combination of salary and cost-containment incentives. MCOs that write contracts with strict cost-control incentives have lower costs and lower premiums but they also have a harder time recruiting physicians to their network of providers than other MCOs do. In equilibrium, MCOs will segment the market. Some will operate with stringent cost-control incentives, small physician panels, and low premiums. MCOs in this part of the market profit by attracting cost-conscious customers. Other MCOs will have more lax cost-control incentives, bigger provider panels, higher premiums, and they profit by attracting customers who put a greater emphasis on provider choice than they do on the cost of insurance. This product differentiation creates disparities in treatment because physicians will use more resources treating policyholders in the high-cost MCOs than the low-cost MCOs. Given the many agency problems in this setting, an increase in competition is likely to cause a decline in medical costs – what some have referred to as a ‘race to the bottom.’

Suppose now, that a physician norm against treatment disparities is introduced, perhaps because physicians do not like to deliver care that uses fewer resources than that delivered by other physicians in the market. This norm makes it more difficult for low cost plans to attract physicians and so they must pay them more (while also reducing cost-containment incentives). With low-cost plans behaving more like high-cost plans, there is less product differentiation and no race to the bottom. Indeed heightened competition reduces product differentiation and increases the overall level of resource utilization in the market. In this way, norms of professional practice can help explain why the managed care revolution of the 1990s failed to deliver on its promise to control the rise of medical costs. The model also can account for the absence of the widely predicted ‘race to the bottom’ in the managed care market of the 1990s.

Coordination, Specialization, And Innovation

The economic ideas discussed so far have been primarily concerned with the problem of motivating physicians. A second less well-developed economics literature focuses on problems of coordinating care among physicians who must specialize in specific aspects of care because no single individual can master all medical knowledge.

In his famous dictum that specialization is limited by the extent of the market, Adam Smith neatly summarized the role that markets play in coordinating the activity of highly efficient, specialized producers. More recent work has augmented Smith’s analysis by considering the amount of specialization that will emerge in different economic settings.

Specialization increases the productive efficiency of a team performing complementary tasks. As specialization increases, however, so does the size of the team as well as the costs of coordinating activities among the increasingly specialized producers. These coordination costs are determined by available technologies, especially communication and transportation technologies, but they can also be influenced by agency problems. Increases in the stock of knowledge increase the payoff to team members of investing in more specialized knowledge. Heightened specialization, it turns out, also increases the payoff to generating new knowledge. Applied to medicine, this suggests a positive feedback in which dramatic increases in medical knowledge coincide with dramatic increases in the number of narrow medical subspecialties.

The trade-off between coordination costs and specialization can be used to analyze the growth of hospitalists. Hospitalists are a new medical subspecialty whose purpose is to care for patients when they are hospitalized and then return them to the care of their primary physicians after discharge from the hospital. Primary-care physicians have superior information about their patient’s specific situation and handing off inpatient care to hospitalists creates the risk that key information will not be communicated. For this reason, the rise of the hospitalist specialty creates coordination costs that were not present under the traditional US model in which primarycare doctors supervised their patient’s care in both ambulatory and inpatient settings. Improvements in communication technologies have the effect of reducing coordination costs and thus increasing the demand for hospitalists, but this is not the whole story.

Coordination costs are also determined by the switching costs of moving from ambulatory to inpatient settings. It is costly for physicians to switch from office-based care to visiting their hospitalized patients, and some of these costs are fixed (think of the time and effort costs of leaving the office and traveling to the hospital to see patients). In the presence of these fixed switching costs, anything that reduces the number of patients a physician has in the hospital will reduce a primary-care physician’s willingness to supervise their patient’s inpatient care. For this reason, reductions in hospital length of stay, increases in the use of outpatient procedures in doctors’ offices or even a reduction in physician work hours and patient load can have the effect of increasing demand for hospitalists.

The efficiency gains from specialization are not the only gains from the use of hospitalists. Hospitalists are often employed by hospitals but they may also work as contractors employed by outside firms or physician groups. Whatever their formal status, hospitals are likely to have more influence over hospitalist activities than they do over independent, primarycare physicians. Hospitals will therefore find their hospitalists relatively easy to engage in process improvement initiatives. By the same token, however, hospitals might use this heightened influence to encourage their hospitalists to shift costs onto other parts of the healthcare system. Recent findings about the effect of treatment by hospitalists on Medicare patients give some cause for concern in this regard.

The theories of specialization discussed so far are appealing, but they do not consider the referral patterns observed in medicine. In medicine, primary-care providers are generalists trained to recognize and treat common and less difficult conditions. When less common or more difficult patients arrive, the primary-care physicians refer them to specialists who have the extra training and experience required to handle these cases. It follows from this that a fall in the time and effort cost of communication with specialists increases the number of conditions that primary-care physicians will refer to specialists whereas a fall in the costs of learning about rare conditions (e.g., via internet search) broadens the number of cases the primary-care providers will handle themselves.

The process of referral from generalist to specialist creates an agency problem. Consider, for example, a patient who approaches her primary-care doctor for treatment for a rash. The primary-care physician can either refer the patient to a dermatologist or treat the condition themselves and generate extra revenues. If the dermatologists’ in-depth knowledge leads to superior and cost-effective treatment, the referral is efficient. Efficient referrals may not occur, however, if the primary-care physician loses too much revenue by referring the patient. Although there may be little concern that an internist will fail to refer a breast cancer patient to a breast surgeon and oncologist, there are a very large number of conditions that fall into a gray area where the skills and knowledge of the generalist and specialist overlap.

In medicine where generalists make the decision to refer to more highly trained specialists, professional partnerships may have a distinct advantage. This is because the revenue sharing agreements in these partnerships allow the referring primarycare doctor to earn some money from the fees the specialist generates. This suggests that to best realize the advantages of efficient referrals, multispecialist groups ought to be composed of physicians working in areas where agency issues are likely to arise. Thus there might be good incentive reasons to include internists and dermatologists in the same group, but not cardiac surgeons.

As already observed, innovation in healthcare has resulted in a division of labor in which specialists with advanced training focus on the most difficult and advanced sort of medical practice. It is also possible, however, that innovations in treating the most common and routine sorts of care might also be very important.

Consider that healthcare delivery in the US must be concerned with treating two very different kinds of medical issues. One the one hand, there are the difficult, hard to assess cases that require sophisticated pattern recognition and nonroutine decision making by the physician (think, here, of the many conditions featured on the TV show ‘House’ whose etiology or treatment protocol is murky). On the other hand, there are the familiar cases whose treatment can be handled by clear, evidence-based protocols. In the typical physician practice, the responsibility for both of these cases falls to the physician. This division of labor makes some sense as individual patients can unexpectedly acquire one or the other type of condition, and their primary-care physician is in an excellent position to coordinate care across both these types of issues. But this approach to coordinating care also increases costs and dampens important innovation. Care for the protocol-based conditions, if broken out of the physician’s practice, will be less expensive because the caregiver is not an expensive or highly trained generalist. In addition, organizations that specialize in protocol-based care for common issues can use the techniques of modern management to implement continuous improvement processes that drive down costs and improve effectiveness. The job of implementing these techniques will be made simpler by the fact that physicians will not play a central role in these organizations. More provocatively there is evidence from other industries suggesting that innovations originating in the low-cost, low-prestige parts of an industry often end up transforming the production processes required for high-end goods and services as well. If this pattern holds true for medicine, improvements in the delivery of care through ‘miniclinics’ and other limited care delivery operations may end up increasing the rate of innovation in the entire industry.

Prospects For Accountable Care Organizations

ACOs are an organizational innovation created as part of the Medicare Shared Savings Program of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act that was signed into law by President Obama in 2010. Although ACOs are only a small part of a huge piece of legislation, they have attracted a great deal of attention from policy-makers, physicians, and managers.

ACOs are a network of hospitals and providers that contract with the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to provide care to a large bloc of Medicare patients (5000 or more). The contracts, which last for 3 years, create a single risk-bearing entity with incentives to control costs. ACOs that come in under their specified cost benchmarks earn a fraction of the savings. To receive these payments the ACO must also meet stringent standards on 65 quality indicators that reflect patient and caregiver experience, care coordination, patient safety, preventative health, and health of at-risk frail and elderly populations.

It is interesting to consider the ACO experiment from the perspective of organizational economics. For the statistical reasons we discussed in the Section on principal-agent models ACOs must enroll large numbers of Medicare patients in order to generate reliable measures of savings. But, as emphasized, implementing pay for performance in large groups creates free-riding problems that can dramatically weaken incentives. Put differently, if the ACO is comprised of independent contractor physicians connected only by a common hospital and a common incentive plan, they are unlikely to achieve the desired changes in provider behaviors. Selection, socialization, training, and careful job design are what gives a large organization the ability to influence the behavior of physicians in large groups. If these elements are missing, it is hard to see ACOs having much effect on the way healthcare is delivered.

To achieve savings, the ACO has to manage the capabilities of hospitals and the primary-care physicians who make up of the ACO. The most straightforward way to manage these very different capabilities would be for hospitals to simply employ physicians, but as discussed there are historical, legal, strategic, and sociological obstacles to achieving this goal. Simply purchasing physician practices, as many hospitals, and PHOs did during the 1990s, will not do the trick, but it may not be necessary for ACOs to employ all their primary-care physicians. Some organizations appear to be able to incorporate a significant number of nonemployed physicians into ACO-like arrangements and this offers some hope for expanding the range of hospital–physician coordination. A critical element in these organizations is to build legitimacy among independent physicians by making them part of the governance of the organization.

Incorporating specialists into the ACO will be challenging because specialists are not required to limit themselves to a single ACO. The economic model of referrals suggests that ACOs can reduce referrals by introducing training and computer-assisted decision support that make it easier for generalists to substitute their own decisions for those of the specialists. It may, for example, be better to train primary-care physicians to treat rashes and acne rather than sending every case of rash or acne to a dermatologist. However, the vast explosion in medical knowledge implies that there are limits to the substitution of generalist for specialist care. In this case, it may be that efficiently managing referrals to specialists will entail bringing some specialists into the ACO. Keeping these specialists fully occupied will also exert upward pressure on the optimal scale of ACOs.

Given their size, it is likely that free-riding issues will cause ACOs to operate with under-powered incentives, i.e., with incentives that are too weak, by themselves, to elicit meaningful changes in behavior. From this perspective it is helpful to think of the ACO’s incentive problem as analogous to the provision of effort when effort is a public good. The experimental literature on public goods provision suggests that the effects of incentives on public good provision depend critically on the ‘meaning’ agents give to the incentive. Well-designed incentives should communicate that they are intended to achieve a socially beneficial outcome rather than threatening individual autonomy or sense of justice. Extending this logic to the case of intrinsically motivated physicians; managing ACOs likely involves paying careful attention to assigning meaning to the payments, but it is unclear if this meaning is more easily constructed within conventional employment relationships or within hybrid organizations in which doctors participate under looser arrangements. Given the medical profession’s long history of battling to preserve its status as an autonomous and learned profession, low-powered incentives in ACOs built on a hybrid organizational form might be workable. However, conventional organizations may have greater opportunities to train, screen, and socialize for physicians who might respond well to low-powered incentives.

To the extent that successful ACO’s have organizational capabilities that rely on training, screening, socialization, and constructing the ‘meaning’ of incentives they likely also involve relational contracts. Relational contracts are based on informal trusting arrangements whose credibility is enforced by the continuing value of the relationship between parties. The great advantage of relational contracts for ACOs is that they can complement more formal relationships such as those involved in pay for performance. Incentives that would be under powered in the sense of a principal–agent model may be quite a bit more effective if performance this period determined the continuation of a valuable ongoing relationship. Relational contracts can also be used to reduce some of the distortions of high-powered formal incentives.

Taken together, our analysis suggests that as a policy intervention, ACOs are likely to have the biggest effect where care is already integrated. Advocates of ACOs know this and see ACOs as emerging from five different practice arrangements. In order of ease of implementation these are: integrated delivery systems that combine insurance, hospitals, and physicians; multispecialty group practices; PHOs; IPAs, and virtual physician organizations.

Conclusions

This article applies the conceptual tool-kit of organizational economics to the economics of physician practices. Our discussion has focused on three broad themes from organizational economics: PA problems (both conventionally economic and behavioral); inefficiencies in the market for organizational form (resulting from social norms and various market failures); and the trade-off between the productivity gains from specialization and the coordination costs specialization entails.

These themes have been applied to important features of physician practices. Much of the attention has focused on understanding the stubborn persistence of fragmented care delivery via small, physician-owned practices, but other important issues have been considered as well. These include: the mixed record of pay for performance – especially in large healthcare organizations; the difficulties of achieving efficient levels of referrals between generalized and specialized providers; and the emergence of a fast-growing new medical specialty, hospitalists, as a result of changes in the tradeoffs between specialization and coordination costs. The final section brings all the themes together in an assessment of the prospects for ACOs, an important public policy initiative in the US aimed at reforming both incentive systems and the organizational forms within which care is provided.

In each of the applications it was found that the ideas of organizational economics yielded genuine and sometimes unexpected insights. This gives one some confidence that the idiosyncratic features of physician practices do not invalidate insights gleaned from the study of other, more standard, economic entities. In the long-struggle to improve healthcare efficiency, organizational economics will likely help providers, managers, and policy makers better understand how best to coordinate and motivate the physicians who guide patient care.

References:

- American Medical Association (2013). Physician characteristics and the distribution in the United States. Washington, DC: American Medical Association Press.

- Boukus, E. R., Cassil, A. and O’Malley, A. S. (2009). A snapshot of US physicians: Key findings from the 2008 health tracking survey. Data Bulletin. Washington, DC: Center For Studying Health System Change.

- Kane, C. K. (2004a). The practice arrangements of patient care physicians, 1999 (revised). Physician Marketplace Report. Chicago: American Medical Association.

- Kane, C. K. (2004b). The practice arrangements of patient care physicians, 2001. Physician Marketplace Report. Chicago: American Medical Association.

- Kletke, P. R. (1998). Trends in physician practice arrangements. Socioeconomic characteristics of medical practices 1997–98. Chicago: American Medical Association.

- Kletke, P. R., Emmons, D. W. and Gillis, K. D. (1996). Current trends in physician practice arrangements. Journal of the American Medical Association 276(7), 555–560.

- Liebhaber, A. and Grossman, J. M. (2007). Physicians moving to mid-sized, singlespecialty practices. Tracking Report. Washington, DC: Center for Studying Health System Change.

- National Center for Health Statistics (2011). Health United States 2010: With special feature on dealth and dying. Washington, DC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Ohsfeldt, R. L. (1983). Changing medical practice arrangements. Socioeconomic Monitoring Report. Chicago: American Medical Association.

- Staiger, D. O., Aurebach, D. I. and Buerhaus, P. I. (2010). Trends in the work hours of physicians in the United States. Journal of the American Medical Association 303(8), 747–753.