Nurses’ unions are widespread in the developed world. In the European Union, 90% of Denmark’s nurses are members of a union (Danish Nurses’ Organization, 2009), and in the UK, nurses (along with teachers and other professional workers) have the highest union density of any occupation (Metcalf, 2005). Organized labor for the nursing profession is prominent in non-EU countries as well, with nearly one-quarter of Australian nurses belonging to a union (Daly et al., 2004), and 87% of Canadian nurses are represented by organized labor (Informetrica Limited, 2011), though OMalley (2012) reports the figure as lower (62%).

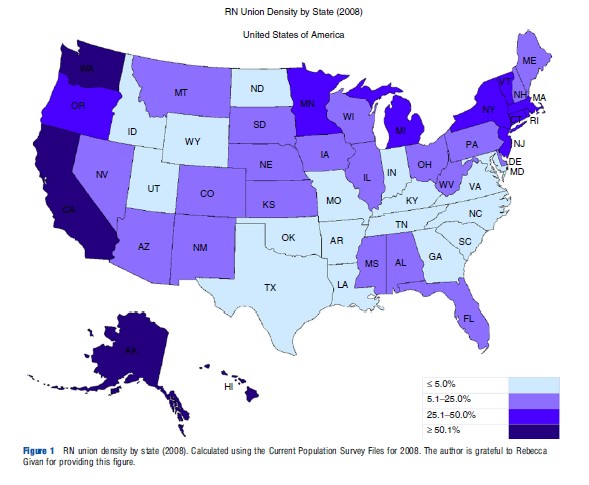

In the USA, the health care sector has been the most active sector of the economy for union organizing in recent years (NLRB, 2004). The percentage of health care practitioners reporting union membership has increased from 12.9% in 2000 to 13.3% in 2010 (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2011), versus a corresponding decrease in overall union membership rates during that time period from 13.5% to 11.9% (Hirsch and Macpherson, 2013a). In addition, the number of unionized health care practitioners has grown by 38% to nearly 960 000 during this same period, versus a 9.5% decrease in the number of unionized members in the overall economy. Union representation among nurses is particularly strong; 18.7% of registered nurses (RNs) were represented by unions as of 2010 (Hirsch and Macpherson, 2013b) and as Figure 1 indicates, these rates are even higher in states such as Washington (61%), Hawaii (55%), California (53%), and New York (46%).

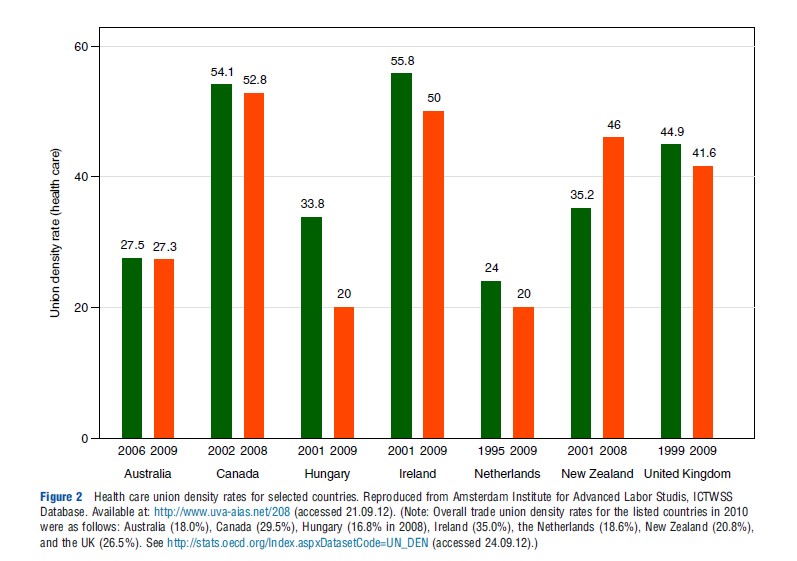

Although a complete international comparison of trends in the union density rate for nurses is limited by data availability, the Amsterdam Institute for Advanced Labor Studies gathers data on the overall health care sector union density rate for a small group of countries, which is included in Figure 2. For each of the seven listed countries, the health care sector union density rate exceeds that of the overall trade union density rate. However, with the exception of New Zealand, the data show a slight downward trend in the union density rate for health care workers.

Nurses play a significant role in the delivery of health care. They are the most numerous health professionals in most Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, with particularly high numbers of nurses per capita in the Nordic countries, Belgium, and Ireland (OECD, 2011a). In the USA, the nursing profession comprises the largest group of health care employees, holding 2.6 million jobs in 2008. Employment in the nursing profession has grown substantially in the past three decades, and if current trends continue, nurse employment is expected to surpass 3 million by 2014 (Health Resources and Services Administration, 2010). In addition, health care production is particularly labor intensive; 60% of hospital costs are labor related (American Hospital Association, 2010) and nursing services constitute the single largest item in most hospital budgets (Public Policy Institute of California, 1996). Consequently, the presence of labor market institutions such as nurses’ unions have the potential to substantially affect both the provision and cost of health care, an industry that accounted for an average of 9.6% of Gross Domestic Product in OECD nations (OECD, 2011b), and greater than 17% of spending in the US economy in 2009 (Martin et al., 2011).

Central to the understanding of the effects of nurses’ unions in the health care sector is the understanding of the two distinct ‘faces’ of unionism. The first, as characterized in Freeman and Medoff (1984), is to exercise market power when bargaining with employers in order to obtain more favorable working conditions for their members, including higher wages, and improved conditions of employment. The other, not necessarily incompatible role of unions is to facilitate a ‘collective voice’ that enables workers to channel their discontent into improved workplace conditions and productivity-enhancing industrial relations policies. Because these forces operate simultaneously within a unionized firm, the fundamental question for understanding the overall impact of unionism relates to the relative magnitude of each of these effects. Consequently, much of the economics literature on unions has focused on an empirical assessment of these two sides of unionism. Several research studies have established that unionized sector workers earn more and have better benefits than their nonunion counterparts (Mellow, 1979; Lewis, 1986; Freeman and Kleiner, 1990; Jakubson, 1991; Wunnava and Ewing, 1999; Hirsch and Schumacher, 2001), whereas evidence on the union productivity effect is less definitive (Fuchs et al., 1998; Doucouliagos and Laroche, 2003; Hirsch, 2007, 2008). Furthermore, as Hirsch (2007) indicates, the importance of each side of unionism is very much dependent on the legal and economic environment in which unions and firms operate, as well as the skill level of the employees who are organized (Card, 1996).

This article critically reviews the literature on nurses’ unions. Because most studies of nurses’ unions rely on data from the USA, in what follows the focus is primarily on the role of these unions in the US economy (unless otherwise noted). The article proceeds in four steps. First, the section ‘‘Organized Labor in the US Health Care Industry’’ provides a brief overview of the legal and regulatory issues surrounding union organizing in the health care industry. The second section ‘‘Nurses’ Unions and the Labor Market for Nurses,’’ summarizes the evidence on the effects of nurses’ unions on the labor market. In the section titled ‘‘Nurses’ Unions and Firm Performance’’ I review evidence on the productivity effects of nurses’ unions on the firms in which they are employed. I conclude by focusing on priorities for future research.

Organized Labor In The US Health Care Industry

The growth of organized labor in the US health care industry is a relatively recent phenomenon when compared with that of other traditionally unionized sectors of the economy. Although initially covered under the prounion Wagner Act of 1935, collective bargaining in health care institutions was limited by the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) of 1947. This Act, which outlined unfair practices on the part of unions, also excluded both government and nonprofit hospitals from the right to unionize, asserting that unionization could disrupt the provision of necessary charitable services and open the way for ‘‘strikes, picketing and violence which could impede the delivery of health care’’ (Zacur, 1983, p. 10). Clark et al. (2002) note that although eight states enacted legislation granting some collective bargaining rights during this time, most employees in the sector did not have a right to unionization.

After intense lobbying efforts by hospital employee organizations, in 1974, President Nixon signed Public Law 93- 360 (PL 93-360) reversing the 23-year exclusion. This law subjected all nongovernmental health care facilities to federal labor law, as governed by the NLRA, and in particular nurses, as 66% of nurses were employed by hospitals at the time (Aiken et al., 1981). In the 4 years following this amendment, there were over 1000 hospital union certification elections (Scott and Simpson, 1989), and an increase in the percentage of hospitals with collective bargaining agreements to 23% in 1976 versus 3% in the early 1960s (Huszczo and Fried, 1988).

In the 15 years following the passage of PL 93-360, a protracted case-by-case bargaining unit determination process enabled hospitals to strategically challenge the bargaining unit determination in each union election, in order to reduce the resolve of employees voting to unionize (Keefe and Rakich, 2004). However, in a final rule published by the National Labor Relations Board in 1989 and affirmed by the US Supreme Court in 1991, eight separate bargaining units were clearly delineated, one of which included registered nurses. Tomey (2004) and Keefe and Rakich (2004) show that this ruling further opened the health care industry to unionization, and increased the number of union elections won in the years following this ruling.

Although these recent protections extended to health care workers have increased the ease with which workers are able to organize, despite these protections, the collective bargaining rights of nurses continue to be disputed. For example, recent cases have disputed the rights of nurses to organize on the grounds that they represent supervisory personnel and are thus exempt from the protections afforded by the NLRA (see NLBR v. Kentucky River Community Care, Inc., 532 US 706, 2001 and Oakwood Healthcare, Inc., 348 NLRB 686, 180 LRRM 1257, 2006). Nonetheless, union representation among nurses remains strong, and is growing.

Nurses’ Unions And The Labor Market For Nurses

One of the most important potential impacts of nurses’ unions is their effect on the labor market for nurses. Unions have been shown to significantly raise wages in the overall economy (Fuchs et al., 1998; Hirsch and Schumacher, 2004), and registered nurses have realized significant gains in wages in the three decades following the passage of PL 93-360. According to the 2010 National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses, real wages (in 1980 dollars) for registered nurses increased by 54% from 1980 to 2008, from US$17 400 in 1980 to nearly US$27 000 in 2008 (average nominal wages for RNs in 2008 were nearly US$67 000). Furthermore, nurses’ unions have recently claimed credit for securing wage increases for their employees, as well as the implementation of employment-related regulation such as minimum nurse-to-patient ratios in California, and the introduction of federal minimum staffing legislation in Congress (California Nurses Association, 2009).

Effects on Employee Compensation

Despite the growing numbers of unionized nurses in the USA, most studies analyzing the effects of nurses’ unions on wages are somewhat outdated. Before the passage of PL 93-360, evidence of only a small and sometimes statistically insignificant union wage effect was found in studies relying mostly on data from aggregate metropolitan areas or statelevel data for their estimates (Feldman and Scheffler, 1982). Link and Landon’s (1975) analysis of the interaction of union and monopsony effects was a notable exception during this period, in that it used a hand-collected data set from individual hospitals. Their results show a 5–10% gain in the wages for hospital nurses due to unionization, with particularly strong gains for lower skilled nurses.

Following the change in the NLRA in 1974, a number of studies attempted to quantify the effects of unions in hospitals, and most focused at least in part on the effects of union membership on nurses. Feldman and Scheffler (1982) use a national probability sample of hospitals drawn from the American Hospital Association (AHA) survey, and present results indicating that both hospitals and unions have market power. Their findings indicate an overall effect of unions on nurses’ wages of approximately 8%, with more substantial wage gains for unions established for at least 10 years at the time that their sample was collected. Adamache and Sloan (1982) in their study of a sample of hospitals in 1979 find a smaller union wage premium of 5% for hospital nurses, although they do not reject a union wage premium of up to 20%. Their study is also unique in that their estimates imply substantial union spillover effects, equating to a 10% wage premium at surrounding hospitals if 75% of hospitals in a market have formal collective bargaining agreements. Furthermore, their analysis of the effects of market structure on nurse wages finds no evidence that unions possess countervailing power that offsets the effects of monopsony. Groshen and Krueger (1990) also find evidence of a wage premium for nurses of approximately 4%, although their results suffer from similar limitations of earlier studies on union wage premiums in that their unit of analysis is a metropolitan area rather than a hospital.

Two more recent studies by Schumacher and Hirsch (1997) and Hirsch and Schumacher (1998) adopt a distinctly different approach to identifying the union wage premium for nurses, arguing that measurement of the union wage premium using firm-level data, as has been attempted in previous studies, may distort the true union wage premium. Specifically, they emphasize the potential for overstating the true union wage premium if such a wage differential corresponds to unmeasured skill differentials across unionized and nonunionized workers. Hirsch and Schumacher (1998) demonstrate that although cross-section regression estimates of the union wage premium in their sample produce a statistically significant union wage premium estimate roughly equivalent to those found in previous studies (approximately 3.2%), a specification that estimates the union wage premium using the change in wages for individuals who switch into or out of union membership over a 1-year period suggests a statistically insignificant estimate of 1.1%. This implies that the cross-section union wage differential may represent a compensating differential for unmeasured worker ability. Schumacher and Hirsch (1997) further this point in their work analyzing the magnitude of hospital wage premiums, finding a substantial wage premium realized by hospital nurses, with little of this premium due to union membership. Though the authors acknowledge that their identification strategy is likely to bias the results toward an underestimate of the true union wage effect, their findings parallel those of Bruggink et al. (1985) who find no direct impact of nurse unions on RN wages.

In the only analysis of the effects of unions on the distribution of wages, Spetz et al. (2010) find little difference in the pay structure of unionized versus nonunionized nurses. Though a number of their findings fail to achieve statistical significance, notable in their study are results indicating that nurses’ unions decrease the disparities in income between nurses with dissimilar levels of education, and also lower the return to experience for unionized nurses. They conclude that, contrary to Freeman (1980, 1982), who found strong evidence that unions reduce wage dispersion and rationalize the wage structure, unions’ primary effect in hospitals is to raise wages with no noticeable effects on the wage distribution.

Explanations For The Evidence On Union Wage Premiums For Nurses

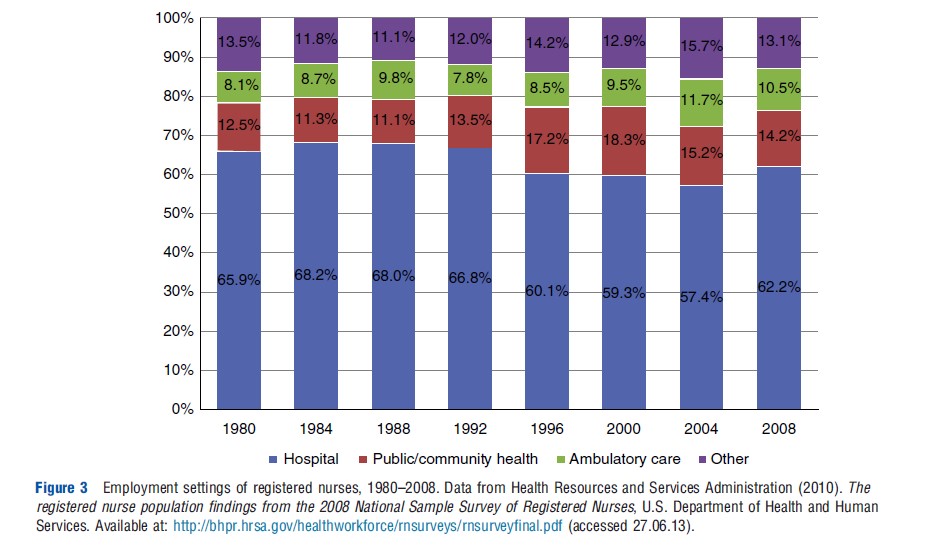

Although the estimates of the union wage premium for nurses is substantially lower than the 15% average effect that persists in the overall economy, a number of factors likely contribute to the underestimation of the true premium. First, as Kaufman (2007) notes, the effects of unions may vary when wages and employment are not determined within a competitive labor market. Reports of nursing shortages in the USA in every decade since the 1950s, coupled with the concentration of nursing employment in relatively few settings, have led economists to characterize the nursing market as the ‘‘textbook example of monopsony’’ (Hirsch and Schumacher, 2004, p. 1). Figure 3 indicates that approximately 60–70% of nurses are employed by hospitals, and more than 85% are employed by either hospitals, ambulatory care, or community health centers.

The existence of monopsony power can generate union wage effects that differ from those predicted by the standard competitive model where the market power of unions over labor supply is assumed to enable them to bargain for higher wages. Specifically, a union’s market power in a monopsonistic labor market may be partially offset by an employer’s dominance in the labor market, resulting in a wage level closer to that which would prevail in a competitive, nonunionized market. Thus, depending on the relative bargaining position of the firm versus the union within a market, collective bargaining in a monopsonistic labor market could lead to smaller wage premiums than would prevail in a competitive labor market, and studies estimating the union wage premium that omit variables that are correlated with hospital monopsony power could tend to underestimate the true union wage effect. Although empirical support for monopsony is mixed (Adamache and Sloan, 1982; Hirsch and Schumacher, 1995, 2005; Matsudaira, 2010), a sufficient number of studies have found evidence consistent with the presence of monopsony power for firms that employ nurses, which lends credibility to this argument (Hurd, 1973; Link and Landon, 1975; Bruggink et al., 1985; Robinson, 1988; Sullivan, 1989; Currie et al., 2005; Staiger et al., 2010).

Second, both Sloan and Steinwald (1980) and Salkever (1984) find that union effects vary depending on the number of years a union has existed, with greater wage effects found for older, more established unions. Given the relatively new status of nurses’ unions during the period when many of these studies were conducted, the full impact of bargaining may not yet be fully established. Third, as Nicholson (2003) notes, economists such as Pencavel (1984) and MaCurdy and Pencavel (1986) have modeled unions as utility-maximizing entities that negotiate with firms over both worker rents as well as the quantity of union members employed. Although no studies have explicitly focused on the employment effects of nurses’ unions, the inclusion of minimum staffing language in most union contracts (Clark and Clark, 2006), as well as recent efforts by unions to mandate staffing levels at hospitals and nursing homes, is consistent with these models. Finally, Adamache and Sloan (1982), and Hirsch and Schumacher (1998) find evidence of a substantial union threat effect, wherein nonunion employers may offer higher wages to their workers to reduce the threat of unionization. As Ichniowski et al. (1989) indicate, failure to adequately control for threat effects may underestimate the full effect of unions on employee compensation.

Nurses’ Unions And Firm Performance

What unions do to productivity is one of the key factors in assessing the overall economic impact of unions. Given the importance of nurses for the firms in which they are employed, nurses’ unions have the potential to substantially affect firm performance. Health care production is particularly labor intensive, with nurses accounting for 30% of hospital costs (McCue et al., 2003). Nurses are a crucial part of the hospital production function and are, as one hospital Chief Executive Officer said, ‘‘the heart and soul of the hospital’’ (Draper et al., 2008, p. 2). The nursing staff in a hospital is by far the most productive labor input, with a marginal product nearly three times as large as that of any other hospital input (Jensen and Morrisey, 1986).

Hirsch (2007) identifies three routes through which unionization-induced productivity gains can be realized: (1) union-induced wage increases may induce increases in technical efficiency; (2) reductions in turnover costs; and (3) productivity-enhancing personnel policies resulting from increased employee involvement in the production process. Although wage increases have been found to induce factor substitution and reduce quality for nursing homes (Cawley et al., 2006), a number of studies document the beneficial effects of turnover reduction and increased employee involvement in hospital settings in both the USA and the UK (Propper and Van Reenen, 2010; Cebul et al., 2008; Phibbs et al., 2009).

Nurses’ Unions And Hospital Output

Older studies analyzing the long-term performance effects of nurses’ unions in the hospital industry have generally concluded that unions adversely affect health care production, and that the effects are especially relevant for hospitals with an established union presence. Sloan and Steinwald’s (1980) estimates indicate that average hospital costs increase 2–3% in the year collective bargaining is introduced, with larger effects of 4–6% for more established unions. Salkever (1982, 1984) also finds evidence of larger union effects for established unions. His analysis suggests that union impacts on total costs are not positive during the first 2 years of unionization, but that a union presence increases hospital costs by 3.3–9% overall. Though not focused on nurses specifically, Sloan and Adamache’s (1984) analysis of a national sample of AHA member hospitals shows an increase in hospital costs per adjusted patient day and adjusted admission of 3.5% and 4.1%, respectively, at unionized hospitals in which there were no recent incidents of labor strife. Their results are larger for unionized hospitals with a recent strike or job action; costs per adjusted admission in these hospitals are 9–10% higher than at nonunionized hospitals.

Of note in this literature are the suggested mechanisms through which these cost increases occur. Sloan and Adamache (1984) attribute their findings entirely to the cost impacts of the union wage effect, implying no union productivity effect. Salkever (1984) and Groshen and Krueger (1990), however, attribute their findings primarily to nonwage factors. Salkever (1984) estimates that nonwage components account for two-thirds of the cost increase due to unionization, whereas Groshen and Krueger (1990) indicate that unionized hospitals are more limited in their ability to adjust wages and staffing levels than are nonunionized hospitals. Furthermore, both of Salkever’s studies attribute hospital cost increases to employee groups other than nurses; when nurse unions are separately analyzed, he finds negative and insignificant effects of RN unions on costs.

Register’s (1988) analysis of the union effect on hospital production was the first to examine the productivity effects of unions using data collected after the introduction of Medicare’s Prospective Payment System (PPS). Although hospital reimbursement was cost-based before the introduction of PPS in 1983, under PPS, hospitals were reimbursed a fixed amount for each diagnosis-related group regardless of the actual expenses incurred in caring for a patient. Because this created new incentives for efficient operation, it became more important to realize beneficial union productivity effects after the introduction of PPS. His study finds evidence of productivity effects using both a national sample and state-specific data, and indicates that average costs at unionized hospitals are approximately 9% lower than at nonunionized hospitals.

Effects On Quality

Although the aforementioned studies base their conclusions on measures of hospital output such as total discharges and patient days, none of these studies are able to account for the quality of production. Quality is a major concern in health care, and is often thought of as a more important dimension of production than in other industries (Gaynor, 2006). Furthermore, quality is costly; Romley and Goldman (2008) find that an interquartile improvement in hospital quality would increase hospital costs by nearly 50%. Thus, an analysis of the effects of nurses’ unions on hospital production that fails to account for the role of nurses’ unions on the quality of hospital services could lead to erroneous conclusions regarding the full extent to which unions affect productivity.

Seago and Ash (2002) and Ash and Seago (2004) are the only studies to directly address this concern in their study of 344 California hospitals from 1993. Their studies analyze the effects of nurses’ unions on heart attack mortality, using riskadjusted heart attack mortality rates collected as part of a California Hospital Outcomes Project. Their findings indicate that risk-adjusted heart attack mortality rates for hospitals with unionized nurses are 5.5% lower than at nonunionized hospitals. Though their identification strategy cannot rule out the potential for nonrandom selection of unions into highquality hospitals, they argue the potential for the selection of unions into low-quality hospitals is likely as well, given the potential for poor employee morale in these facilities. Consequently, though their study addresses the issue of patient selection in a particularly thorough manner given the constraints of their data, their discussion stops just short of arguing for a purely causal interpretation of their results.

Impact Of The Labor Relations Environment

The state of the labor relations environment can also greatly impact productivity within a unionized firm. A number of multi-industry studies provide evidence that productivity can deteriorate as a result of strikes and labor unrest (Neumann, 1980; Neumann and Reder, 1984; Becker and Olson, 1986; Kramer and Vasconcellos, 1996; Kleiner et al., 2002). Strikes and poor labor–management relations have also been shown to negatively impact the quality of production. For example, Krueger and Mas (2004) found that tire defect rates were particularly high at a tire plant during periods of labor unrest, and Mas (2008) found that workmanship for construction equipment produced at factories that experienced contract disputes was significantly worse relative to equipment produced at factories without labor unrest, as measured by the resale value of the equipment.

Given the importance of nurses to health care production, coupled with the complex nature of health care delivery where workers exhibit a high degree of interdependence (Cebul et al., 2008), it is perhaps not surprising that health care quality has been shown to be particularly susceptible to labor unrest. Mustard et al. (1995) found that the incidence of adverse newborn outcomes increased during a month-long Ontario nurses strike, conjecturing that disruption in the normal standards of care was a contributing factor to the elevated rate of adverse outcomes. Gruber and Kleiner (2012) also find evidence of deterioration in patient outcomes in their study of 50 hospital strikes in New York State. Their results indicate that nurses’ strikes increase in-hospital mortality by 18.3% and 30-day readmission by 5.7% for patients admitted during a strike. Furthermore, their results highlight the importance of employee tenure within a firm, as they find that hospitals staffed by replacement workers during strikes perform no better during these strikes than those that do not hire substitute employees.

Conclusion And Areas For Future Research

Although a considerable literature has investigated the effects of nurses’ unions in the health care sector, the conclusions of this literature are far from definitive. Although the current body of research could be characterized as suggesting that nurses’ unions raise wages and contribute to reductions in firm performance, sufficient evidence exists within this literature to challenge these conclusions. Further research could contribute to our understanding of the role of nurses’ unions in five ways. First, the conclusions of the existing literature are based largely on old data that do not reflect the current state of the health care industry. For example, of the studies examining the production effects of health care worker unions, only Register (1988) uses data from a period following the implementation of PPS, and none of these studies examine the impact of unions after the growth of managed care and subsequent restructuring of the health care system. As Norrish and Rundall (2001) indicate, this restructuring affected aspects of nursing such as staffing ratios, and workload, both of which are likely to affect the role of nurses within the institutions for which they work. Thus, our understanding of the effects of nurses’ unions would greatly benefit from research utilizing more recent data. Second, with the exception of Hirsch and Schumacher’s research on union wage premiums, the aforementioned studies rely on cross-sectional variation to identify their results. Given the potential for selection of unions into firms with higher wages and poor labor relations (which may contribute to reduced productivity), future work should employ updated econometric techniques to better account for this possibility. Third, more work on the impact of nurses’ unions on the quality of hospital production is needed. With the exception of Ash and Seago’s demonstration of a positive relationship between union status and patient outcomes, and Gruber and Kleiner (2012), who find a short-run decrease in quality due to strikes, little attempt has been made to quantify these effects, despite the claims of nurses’ unions that patient care is a priority in negotiations (Clark and Clark, 2006). Fourth, although nurses’ unions are similar in their objectives across countries (Clark and Clark, 2003) and union wage and productivity effects have been documented in a number of developed nations (Blanchflower and Freeman, 1992), little is known about the wage and productivity effects of nurses’ unions in countries other than the USA. Finally, the mechanism by which nurses’ unions affect hospital performance is not well understood. A better understanding of the means by which these unions affect productivity would assist in managerial and public policy decision making.

References:

- Adamache, K. W. and Sloan, F. A. (1982). Unions and hospitals: Some unresolved issues. Journal of Health Economics 1(1), 81–108.

- Aiken, L. H., Blendon, R. J. and Rogers, D. E. (1981). The shortage of hospital nurses: A new perspective. Annals of Internal Medicine 95, 365–371.

- American Hospital Association (2010). Trendwatch chartbook 2010: The economic contribution of hospitals, [Online]. Available at: http://www.aha.org/research/ reports/tw/chartbook/2010/chapter6.pdf (accessed 27.06.13).

- Ash, M. and Seago, J. A. (2004). The effect of Registered Nurses’ Unions of heartattack mortality. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 57, 422–442.

- Becker, B. E. and Olson, C. A. (1986). The impact of strikes on shareholder equity. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 39(3), 425–438.

- Blanchflower, D. G. and Freeman, R. B. (1992). Unionism in the United States and other advanced OECD countries. Industrial Relations 31(Winter), 56–79.

- Bruggink, T. H., Finan, K. C., Gendel, E. B. and Todd, J. S. (1985). Direct and indirect effects of unionization on the wage levels of nurses: A case study of New Jersey hospitals. Journal of Labor Research 6, 407–416.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics (2011). Union affiliation of employed wage and salary workers by occupation and industry, [Online]. Available at: http://www.bls.gov/webapps/legacy/cpslutab3.htm (accessed 24.04.11).

- California Nurses Association (CNA) (2009). The ratio solution: CNA/NNOC’s RNto-patient ratios work – Better care, more nurses. Oakland, CA: California Nurses Association. Available at: http://www.area-c54.it/public/ california%20nurses%20association%202.pdf (accessed 24.05.11).

- Card, D. (1996). The effect of unions on the structure of wages: A longitudinal analysis. Econometrica 64, 957–979.

- Cawley, J., Grabowski, D. and Hirth, R. (2006). Factor substitution in nursing homes. Journal of Health Economics 25(2), 234–247.

- Cebul, R., Rebitzer, J.B., Taylor, L.J. and Votruba, M. (2008). Organizational fragmentation and care quality in the U.S. Health care system. National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 14212.

- Clark, P. F. and Clark, D. A. (2003). Challenges facing Nurses’ Associations and Unions: A global perspective. International Labour Review 142, 29–48.

- Clark, P. F. and Clark, D. A. (2006). Union strategies for improving patient care: The key to nurse unionism. Labor Studies Journal 31(1), 51–70.

- Clark, P. F., Delaney, J. T. and Frost, A. C. (eds.) (2002). Collective bargaining in the private sector. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Currie, J., Mehdi, F. and MacLeod, W. B. (2005). Cut to the bone? Hospital takeovers and nurse employment contracts. Industrial & Labor Relations Review 58(3), 471–493.

- Daly, J., Speedy, S. and Jackson, D. (2004). Nursing leadership. Marrickville, NSW, Australia: Elsevier.

- Danish Nurses’ Organization (2009). Nurse in Denmark? A guide on salary, pension and employment. Available at: http://www.dsr.dk/Artikler/Documents/English/ Nurse%20in%20Denmark.pdf (accessed 05.06.12).

- Doucouliagos, C. and Laroche, P. (2003). What do unions do to productivity? A metaanalysis. Industrial Relations 42, 650–691.

- Draper, D. A., Felland, L. E., Liebhaber, A. and Melichar, L. (2008). The role of nurses in hospital quality improvement research brief, [Online]. Available at: http://www.hschange.com/CONTENT/972/972.pdf (Center for Studying Health System Change) (accessed 09.03.10).

- Feldman, R. and Scheffler, R. (1982). The union impact on hospital wages and fringe benefits. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 35, 196–206.

- Freeman, R. B. (1980). Unionism and the dispersion of wages. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 34, 3–23.

- Freeman, R. B. (1982). Union wage practices and wage dispersion within establishments. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 36, 3–21.

- Freeman, R. B. and Kleiner, M. M. (1990). The impact of new unionization on wages and working conditions. Journal of Labor Economics 8(1, part 2), S8–S25.

- Freeman, R. B. and Medoff, J. L. (1984). What do unions do? New York: Basic Books.

- Fuchs, V. R., Krueger, A. B. and Poterba, J. M. (1998). Economists’ view about parameters, values, and policies: Survey results in labor and public economics. Journal of Economic Literature 36, 1387–1425.

- Gaynor, M. (2006). What do we know about competition and quality in health care markets? NBER Working Paper 12301.

- Groshen, E. L. and Krueger, A. B. (1990). The structure of supervision and pay in hospitals. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 43(February), 134–146.

- Gruber, J. and Kleiner, S. A. (2012). Do strikes kill? Evidence from New York state. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 4(1), 127–157.

- Health Resources and Services Administration (2010). The registered nurse population findings from the 2008 National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available at: http:// bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/rnsurveys/rnsurveyfinal.pdf

- Hirsch, B. T. (2007). What do unions do for economic performance? In Bennett, J. T. and Kaufman, B. E. (eds.) What do unions do? A twenty year perspective, pp. 193–237. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

- Hirsch, B. T. (2008). Sluggish institutions in a dynamic world: Can unions and industrial competition coexist? Journal of Economic Perspectives 22, 153–176.

- Hirsch, B. T. and Macpherson, D. A. (2013a). Union membership, coverage, density, and employment among all wage and salary workers, 1973–2012, [Online]. Available at: Unionstats.com (accessed 31.07.13).

- Hirsch, B. T. and Macpherson, D. A. (2013b). Union membership, coverage, density, and employment by occupation, 2010, [Online]. Available at: Unionstats.com (accessed 31.07.13).

- Hirsch, B. T. and Schumacher, E. J. (1995). Monopsony power and relative wages in the labor market for nurses. Journal of Health Economics 14(4), 443–476.

- Hirsch, B. T. and Schumacher, E. J. (1998). Union wages, rents, and skills in health care labor markets. Journal of Labor Research 19(1), 125–147.

- Hirsch, B. T. and Schumacher, E. J. (2001). Private sector union density and the wage premium: Past, present, and future. Journal of Labor Research 22, 487–518.

- Hirsch, B. T. and Schumacher, E. J. (2004). Match bias in wage gap estimates due to earnings imputation. Journal of Labor Economics 22, 689–722.

- Hirsch, B. T. and Schumacher, E. J. (2005). Classic or new monopsony? Searching for evidence in nursing labor markets. Journal of Health Economics 24(5), 969–989.

- Hurd, R. W. (1973). Equilibrium vacancies in a labor market dominated by nonprofit firms: The ‘‘shortage’’ of nurses. Review of Economics and Statistics 55, 234–240.

- Huszczo, G. E. and Fried, B. J. (1988). A labor relations research agenda for health care settings. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal 1(1), 69–84.

- Ichniowski, C., Freeman, R. and Lauer, H. (1989). Collective bargaining laws, threat effects, and the determination of police compensation. Journal of Labor Economics VII, 191–209.

- Informetrica Limited (2011). Quick Facts prepared for the Canadian Federation of Nurses Unions. Available at: http://www.nursesunions.ca/sites/default/ files/overtime_and_absenteeism_quick_facts.pdf (accessed 04.06.12).

- Jakubson, G. (1991). Estimation and testing of fixed effects models: Estimation of the union wage effect using panel data. Review of Economic Studies 58, 971–991.

- Jensen, G. A. and Morrisey, M. A. (1986). The role of physicians in hospital production. The Review of Economics and Statistics 68(3), 432–442.

- Kaufman, B. E. (2007). What do unions do? Insights from economic theory. In Bennett, J. T. and Kaufman, B. E. (eds.) In what do unions do? A twenty-year perspective, pp. 12–45. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

- Keefe, T. and Rakich, J. S. (2004). A profile of hospital union election activity, 1985–1994: NLRB rulemaking and results in right-to-work states. Hospital Topics 82(2), 2–11.

- Kleiner, M. M., Leonard, J. S. and Pilarski, A. M. (2002). How industrial relations affect plant performance: The case of commercial aircraft manufacturing. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 55(2), 195–218.

- Kramer, J. K. and Vasconcellos, G. M. (1996). The economic effect of strikes on the shareholders of nonstruck competitors. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 49(2), 213–222.

- Krueger, A. B. and Mas, A. (2004). Strikes, scabs, and tread separations: Labor strife and the production of defective bridgestone/firestone tires. Journal of Political Economy 112(2), 253–289.

- Lewis, H. G. (1986). Union relative wage effects: A survey. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Link, C. R. and Landon, J. H. (1975). Monopsony and union power in the market for nurses. Southern Economic Journal 41, 649–656.

- MaCurdy, T. E. and Pencavel, J. H. (1986). Testing between competing models of wage and employment determination in unionized markets. Journal of Political Economy 94(3), S3–S39.

- Martin, A., Lassman, D., Whittle, L. and Catlin, A. (2011). National health expenditure accounts team. Recession contributes to slowest annual rate of increase in health spending in five decades. Health Affairs (Millwood) 30(1), 11–22.

- Mas, A. (2008). Labour unrest and the quality of production: Evidence from the construction equipment resale market. Review of Economic Studies 75(1), 229–258.

- Matsudaira, J. D. (2010). Monopsony in the low-wage labor market? Evidence from minimum nurse staffing regulations. unpublished manuscript, Cornell University.

- McCue, M., Mark., B. A. and Harless, D. W. (2003). Nurse staffing, quality, and financial performance. Journal of Health Care Finance 29, 54–76.

- Mellow, W. S. (1979). Unionism and wages: A longitudinal analysis. Washington, DC: Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor.

- Metcalf, D. (2005). British Unions: Resurgence or Perdition? The Work Foundation, Provocation Series, vol. 1, no. 1. Available at: http://www.theworkfoundation. com/DownloadPublication/Report/68_68_British%20Unions.pdf (accessed 04.06.12).

- Mustard, C., Harmon, C., Hall, P. and Dirksen, S. (1995). Impact of a nurses’ strike on the cesarean birth rate. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 172(2), 631–637.

- Neumann, G. R. (1980). The predictability of strikes: Evidence from the stock market. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 33(4), 525–535.

- Neumann, G. R. and Reder, M. W. (1984). Output and strike activity in U.S. manufacturing: How large are the losses? Industrial and Labor Relations Review 37(2), 197–211.

- Nicholson, S. (2003). Barriers to entering medical specialties. Working Paper 9649. Cambridge MA: NBER.

- NLRB (2004). Sixty-Eighth Annual Report of the National Labor Relations Board for the Fiscal Year Ended 30 September 2003 at Table 16. Available at: http:// www.nlrb.gov/sites/default/files/documents/119/nlrb2003.pdf (accessed 27.06.13).

- Norrish, B. R. and Rundall, T. G. (2001). Hospital restructuring and the work of registered nurses. Milbank Quarterly 79, 55–79, IV.

- OECD (2011a). Health at a glance 2011: OECD indicators. OECD Publishing. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/health_glance-2011-en

- OECD (2011b). ‘‘Nurses,’’ in OECD factbook 2011–2012: Economic, environmental and social statistics. OECD Publishing. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/ factbook-2011-111-en

- OMalley, B. H. (2012). The labor union and the registered nursing profession, [Online]. Available at: http://www.registered-nurse-canada.com/labor_union.html (accessed 31.07.13).

- Pencavel, J. (1984). The tradeoff between wages and employment in trade union objectives. Quarterly Journal of Economics 99(2), 215–231.

- Phibbs, C. S., Bartel, A. P., Giovannetti, B., Schmitt, S. K., Stone, P. W.( 2009). The type of nurse matters: The effects of nurse staffing levels, non-RNs, and contract nurses on length of stay, [Online]. Available at: http://www0.gsb.columbia.edu/ faculty/abartel/Type%20of%20Nurse%20Matters%20-NEJM.pdf (accessed 09.03.10).

- Propper, C. and Van Reenen, J. (2010). Can pay regulation kill? Panel data evidence on the effect of labor markets on hospital performance. Journal of Political Economy 118(2), 222–273.

- Public Policy Institute of California (1996). Research brief: Are hospitals reducing nursing staff levels?, [Online]. Available at: http://www.ppic.org/con-tent/pubs/rb/ RB_1096JSRB.pdf (accessed 27.04.11).

- Register, C. A. (1988). Wages, productivity, and costs in union and nonunion hospitals. Journal of Labor Research 9(4), 325–345.

- Robinson, J. C. (1988). Market structure, employment, and skill mix in the hospital industry. Southern Economic Journal 55, 315–325.

- Romley, J. A. and Goldman, D. (2008). How costly is hospital quality? A revealed preference approach. Working Paper 13730. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Salkever, D. S. (1982). Unionization and the cost of producing hospital services. Journal of Labor Research 3(3), 311–333.

- Salkever, D. S. (1984). Cost implications of hospital unionization: A behavioral analysis. Health Services Research 19(5), 639–664.

- Schumacher, E. J. and Hirsch, B. T. (1997). Compensating differentials and unmeasured ability in the labor market for nurses: Why do hospitals pay more. Industrial & Labor Relations Review 50, 557–579.

- Scott, C. and Simpson, J. (1989). Union election activity in the hospital industry. Health Care Management Review 14(4), 21–28.

- Seago, J. A. and Michael, A. (2002). Registered nurse unions and patient outcomes. Journal of Nursing Administration 32(3), 143–151.

- Sloan, F. A. and Adamache, K. W. (1984). The role of unions in hospital cost inflation. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 37, 252–262.

- Sloan, F. A. and Steinwald, B. (1980). Hospital labor markets: Analysis of wages and workforce compensation. Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath.

- Spetz, J., Ash, M., Konstantinidis, C. and Herrera, C. (2010). The effect of unions on the distribution of wages of hospital-employed registered nurses in the united states. Journal of Clinical Nursing 20, 60–67.

- Staiger, D., Spetz, J. and Phibbs, C. (2010). Is there monopsony in the labor market? Evidence from a natural experiment. Journal of Labor Economics 28(2), 211–236.

- Sullivan, D. (1989). Monopsony power in the market for nurses. Journal of Law and Economics 32, S135–S178.

- Tomey, A. M. (2004). Guide to nursing management and leadership. 7th ed. Missouri: Mosby.

- Wunnava, P. V. and Ewing, B. T. (1999). Union–nonunion differentials and establishment size: Evidence from the NSLY. Journal of Labor Research 20, 177–183.

- Zacur, S. R. (1983). Health care labor relations: The nursing perspective. Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press.

- Bennett, J. T. and Kaufman, B. E. (eds.) (2007). What do unions do? A twenty year perspective. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

- Buerhaus, P. I., Staiger, D. O. and Auerbach, D. I. (2009). The future of the nursing workforce in the United States. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett.