Dentistry is the field of medicine that is concerned about diseases of the teeth and other tissues and bone structures in the oral cavity. It is different to a degree from other medical services in its product attributes, market characteristics, and the level of government involvement. Although dental disease is not completely predictable, it is less random than other diseases and disorders, some of which can have potentially immediate catastrophic effects. In addition, preventative services make up a much larger portion of the care provided than for other health care services. When treatment of dental caries (tooth decay) is needed, patients are often presented with the option of restoration or removal. This type of choice may not exist for many other medical problems. These characteristics of dentistry allow consumers more flexibility in when and what they purchase. In addition, consumers are generally better informed about dental services. They can often observe and identify their disorder and have more contacts and familiarity with the limited number of dental diseases, diagnostic tools, and procedures than they would with conditions in other fields of medicine. Although poor dental health can affect one’s general health in many ways over time and impede workforce performance and childhood development, dental diseases are not communicable unlike some diseases. Dentist services are generally provided by small, independently owned providers in a situation approximating pure or monopolistic competition in contrast to physicians who are more likely to be organized in larger consortia of providers such as hospitals and health groups with significant local market control. These features suggest that dental care may function more like a standard product market than other health care services where market failures are more pronounced.

Oral health has improved markedly in high-income countries over the last several decades. In contrast, many low-income countries have experienced deterioration in oral health in recent years. The improvements in high-income countries can be attributed to a variety of factors, including increasing incomes, expanded access to dental insurance, improved technology, dietary changes, and fluoridation. Many developing countries are seeing an increase in the prevalence of dental caries, largely due to an increase in consumption of sugars and inadequate exposure to fluorides.

In the US, dental service prices have increased at a much faster clip than other goods and services and even slightly faster than other medical services. However, expenditures on dental care are still a relatively small share (less than 5%) of total health care costs in the US. Unlike the large expenditures going toward medical care, the public sector in the US funds only approximately 6% of the costs. Most of the funds are for low-income children’s programs (i.e., Medicaid and CHIP) and military and veterans care. Private insurance accounts for about half of spending with out-of-pocket funding the residual.

There are also notable differences in the physician and dental workforces. Dentists make up a relatively large percentage of the total health care provider labor force, with an estimated 181 725 active dentists in the US in 2010 compared to 784 199 active physicians who work on all other parts of the body combined. However, although approximately 80% of physicians are specialists and 20% are general practitioners, the reverse is true for dentists. Moreover, dentists are increasingly more likely to rely on auxiliaries to assist with dental procedures and to provide preventative care. New laws and legislation have been introduced to expand the range of services provided by auxiliaries even further. In contrast, other countries, such as New Zealand and the UK, rely more extensively on the use of mid-level oral health care providers.

Although problems in dentistry have featured less prominently in discussions about health care reform, the field is presented with its own set of challenges. Industrialized countries such as Japan and many members of the European Union offer public dental insurance. In the US and elsewhere, a relatively large percentage of the population is uninsured, resulting in serious inequities in access to care. In the US, disadvantaged individuals, minorities, and rural residents are much less likely to exhibit good oral health. In addition, dental labor markets may not work as efficiently as they could if they were less impeded by licensure/regulatory requirements that do little to enhance patient welfare.

The following sections examine these areas in further detail in order to provide a more comprehensive picture of the economics of dentistry in the present day. The first section looks at the chief focus of dentistry: improving oral health. It reviews determinants of oral health, the economic and general health consequences of poor oral health and trends in oral health outcomes. The second section examines dental demand and its determinants, including availability of insurance, time and out-of-pocket costs, public programs, oral health conditions, and other factors. The third section reviews important issues with respect to dental service supply including the supply and distribution of dentists. The fourth section considers the expanding role of other dental care providers in the US and elsewhere.

Oral Health

Determinants Of Oral Health

There are many factors that ultimately determine an individual’s oral health, including oral hygiene habits and behaviors, dietary choices, tobacco use, genetics, use of dental services, income, tastes and preferences , and age. One way to conceptualize individual choice about oral health outcomes is to use Grossman’s well-known model of health capital in which individuals choose between spending time producing health and purchasing medical services. Health depreciates with age, whereas education increases one’s efficiency at producing health at all ages. In the dental context, people demand oral health. Oral health can be produced with various productive inputs. Individual behavior, such as brushing and flossing regularly and consuming less sugar, constitutes one type of input. Other inputs can be purchased such as checkup exams, cleanings, filling and caps for carious teeth, or extraction and replacement with bridges and dentures. People can also consume other goods, such as fluoridated water or fluoride supplements that improve oral health. How much of each input a person purchases in the market depends on a variety of factors including the price or opportunity cost of the services, the present quality of teeth, tastes and preferences for good teeth, age, etc. Applying Grossman’s model to oral health, people demand less dental care as the cost of care and the time needed to produce oral health increases, suggesting people do make trade-offs between good teeth, consumption of other goods, and time.

People vary in their tastes and preferences for good oral health outcomes. Studies have found lower perceived need for care in rural areas and among individuals with a low socioeconomic status, which may be due to the social environment and expectations for good teeth. Family environment, particularly among children, is an important factor in health outcomes. In the US, whether a parent visited a dentist is strongly correlated with whether the child also had a dental visit. Similar results are observed in China. A survey of adolescents (11, 13, and 15 years old) from eight Chinese provincial capitals found that there is a strong relationship between oral health behaviors and the socioeconomic status of parents, school performance, and peer relationships. Looking at Medicaid programs, even when states increased children’s Medicaid provider compensation to levels comparable to private insurance, utilization rates do not rise to the level of those with private insurance. The lower utilization rates suggest that there are significant nonfinancial barriers among low-income populations in seeking dental care, which could be interpreted as a lower preferences for good oral health outcomes, increased costs of gaining access to dental services or a shortage of providers.

Age also plays a role in the demand for oral health care services. In the US, the elderly tend to have low utilization rates. In 1999, 53.5% of adults 65 and older reported that they had visited a dentist, the lowest rate of any adult age group. Although costs are a factor, even when services are available for free or at a reduced cost or when insurance is available, utilization only increases slightly. Low income and less educated elders often have lower expectations of good oral health in their old age. As a result, they may be more accepting of pain as a normal part of aging rather than an indicator of the need for oral health care.

Consequences Of Poor Oral Health

Economic Consequences

Oral disease has negative economic consequences for both individuals and society. Oral disease increases consumers’ direct spending on care and also creates indirect expenditures through lost worker productivity. These expenditures could be reduced with a greater investment in preventative care including better oral hygiene habits, decreased prevalence of families consuming unflouridated water, and greater use of dental sealants and fluoride varnish.

Adults also suffer reduced hours of work and earnings when burdened with oral disease. Much of the loss in hours of work appears to accrue to lower income individuals and is often a result of delaying treatment until symptoms are severe. Time lost from work tends to be correlated with previous time lost, low income, being nonwhite, and having poorer oral health. Interestingly, preventative visits account for the most episodes of lost time, but the fewest hours of lost work, suggesting that delaying treatment resulted in greater treatment need. Not only is there a loss in productivity due to the time needed to receive treatment, but poor oral health also appears to affect earnings more generally. The implementation of community water fluoridation during childhood increases earnings for women by 4%, but does not have an effect on men’s earnings. These findings are consistent with a differing effect of physical appearance on earnings of women and men.

Among children, oral disease is correlated with greater absenteeism and poorer academic performance. For example, children with oral health pain are three times more likely to miss school due to pain and that missing school due to pain results in poorer school performance. However, the absence for routine oral care is not correlated with poor school performance.

Medical Consequences

Traditionally, oral health was viewed in terms of esthetics or localized pain and was compartmentalized from overall health. Recent research, however, has found numerous links from oral health to overall health and well-being, including a correlation with general health, nutrition, digestion, speech, social mobility, employability, self-image and esteem, school absences, quality of life, and well-being. Both bacteria and inflammation resulting from oral disease appears to have a negative association with other chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, stroke, adverse pregnancy outcomes, respiratory infections, diabetes, and osteoporosis.

Oral Health Over Time

Over the past few decades, oral health has improved dramatically for the average individual in high-income countries. Adults have fewer dental caries, the prevalence of dental sealants has increased, and the elderly are less likely to have edentulism (i.e., the loss of some or all teeth) and periodontitis. Over the past few decades, the prevalence of cavities in US children has declined, as has the mean number of missing teeth and percentage of edentulous adults. Among the reasons for this general trend are increased utilization of dental care caused by expanded dental insurance coverage and higher incomes, improved quality of dental care, better oral hygiene practices, widespread adoption of fluoridation in public water supplies and fluoride in dental hygiene products, and greater prevalence of sugar substitutes.

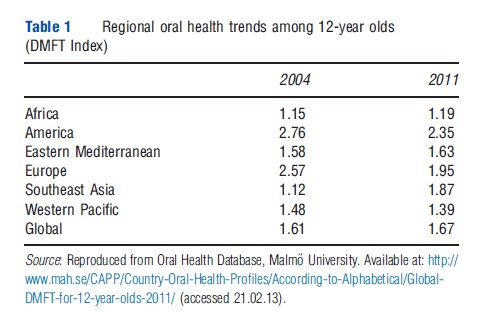

Worldwide, trends in oral health are more mixed. International comparisons of oral health typically rely on the Decayed, Missing and Filled (DMFT) Index. In general, high-income countries have high, but decreasing rates of dental caries. Lower income countries tend to have low levels of dental caries, but the prevalence of caries is increasing. In recent years, there have been an increase in the DMFT index for 12-year olds in the World Health Organization Regions of Africa, Eastern Mediterranean, and Southeast Asia, but a decrease in the Americas, Europe, and the Western Pacific (see Table 1). The result is that the difference in caries experienced by high and low-income countries over the past two decades has narrowed. The consequence of low levels of oral health care can also be observed in the likelihood of caries being treated. In low-income countries, almost all caries remain untreated, in middle-income countries the proportion of the DMFT index that is filled is only 20%, and in high-income countries the rate is 50%. Within all countries sociobehavioral risk factors play a significant role in oral health outcomes. The increasing consumption of sugar, particularly in areas with inadequate fluoride, and high use of tobacco, is a major risk factor.

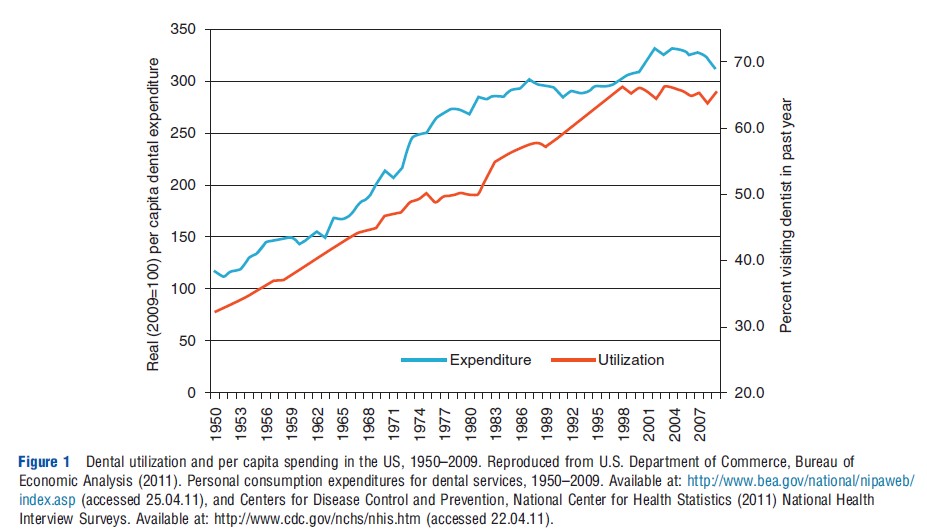

In the US, utilization of dental services, defined as the percent of adults with a dental visit in the past year, increased dramatically from a little more than 30% in 1950 to more than 65% in 2009 (see Figure 1). Real per capita expenditures have more than doubled over the same time period from $116 to $312 per person. As a result of general improvements in oral health, demand for dental services has shifted toward preventative, diagnostic, and cosmetic care and away from restorative work.

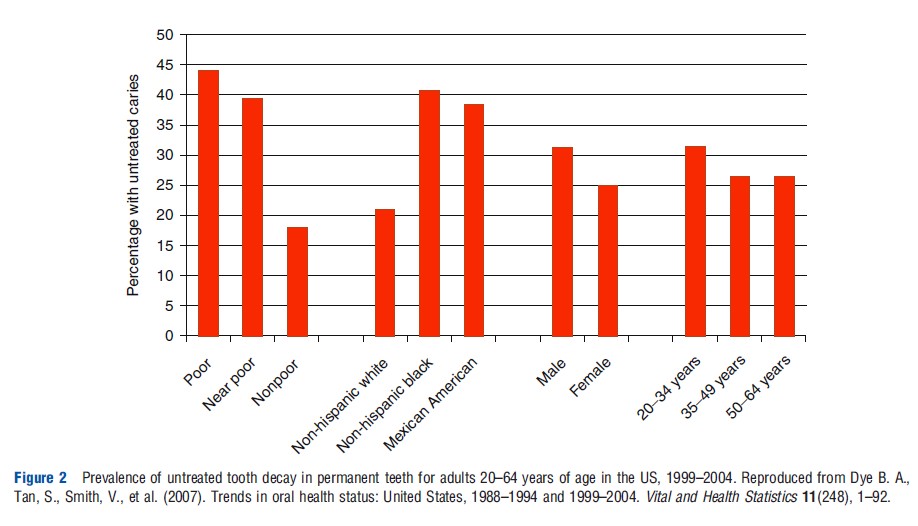

Despite this general trend, there are still segments of the US population that have continued to suffer from generally poorer oral health, such as low-income, minority, and rural populations. Adults 20–64 years of age who are below or near the poverty level (less than 200% of the Federal Poverty Level) are more than twice as likely to have untreated tooth decay than the nonpoor (see Figure 2). Moreover, black and Mexican-American adults are twice as likely to have untreated tooth decay as whites. Similar disparities are found among children. The rate of untreated dental disease among low-income children is significantly higher than that of high-income children. Among 14-year-old white children, the use of dental sealants, a preventive service, is almost four times that among African-American children.

Rural US populations often have poorer oral health than their urban counterparts. Among the reasons for the disparity are lower rates of dental insurance and higher rates of poverty. There are also differences in culture and environment, which may affect the perceived need for dental care. Lower levels of water fluoridation due to reliance on wells and small water supplies may also play a role. Beyond these factors, rural populations also must contend with a lower per capita supply of dentists and longer distances to providers. In 2008, there were22 nonspecialist dentists per 100 000 population in rural areas in the US and 30 per 100 000 in urban areas. Additionally, a higher proportion of rural dentists were more than 55 years old.

Determinants Of Dental Demand

Private Insurance And Income

Countries vary in their use of public or private dental insurance. By reducing the out-of-pocket cost of care, dental insurance can be an important component in the decision to seek dental care. Having private dental coverage significantly increased the proportion of individuals visiting a dentist. In the US, approximately 54% of the population has private dental insurance and 12% has public insurance, leaving 34% without coverage at all. Among those with private dental coverage, 56.9% had a dental visit, whereas only 32% with public coverage had a dental visit and 27% with no dental coverage had a dental visit in 2004. Among people with a dental visit, having insurance is associated with more visits per year and higher dental expenditures. However, some positive correlation between dental insurance and utilization would be expected due to adverse selection. Individuals who expect to need dental care are more likely to buy coverage. Thus, those with insurance would be expected to have higher rates of utilization.

The extent of dental insurance used in other industrialized countries varies. For example, in Norway dental care is provided by private practitioners without public or private insurance, whereas Sweden offers dental services to all adults either free of charge or with a large subsidy. In low-income countries, dental insurance is rare. Oral health services are often provided at urban hospitals where the focus is on pain relief and emergency care rather than prevention or restoration.

Income is also an important component of dental utilization. Of those who are poor in the US only 26.5% had at least one dental visit, whereas the rate was 57.9% among high-income individuals in 2004. However, higher income families are much more likely to have dental coverage. Nonetheless, even after controlling for dental coverage, lower income individuals without coverage are less likely to report a dental visit.

Out-Of-Pocket Monetary Cost

Not only is having dental insurance important, but also the generosity of coverage matters. Unlike medical insurance, dental care routinely requires a substantial out-of-pocket payment. In the 10 largest US states, for example, 49.1% of dental expenditures are paid out of pocket, relative to 16.2% for all health care expenditure. Furthermore, utilization of dental services increases significantly as cost-sharing declines. Enrollees in free plans have 34% more visits and 46% higher dental expenses than enrollees in the 95% coinsurance plan. The mix of dental services may also be sensitive to the degree of cost sharing where prosthodontics, endodontics, and periodontics are more responsive to changes in coinsurance. In general, insurance has had a pronounced effect on the use of more expensive dental care, almost doubling the likelihood that a user will obtain bridge work and increasing the probability of a crown by 38%. Dental insurance, however, has had little or no effect on the use of X-rays and dental cleanings.

Evidence from the RAND Health Insurance Experiment, conducted between 1974 and 1982 in the US, found that dental services were significantly more responsive to cost sharing than other out-patient health services during the first year, but not during subsequent years. The high response during the first year was due to a transitory surge, with individuals taking care of a backlog of problems when low-cost or free care became available. This response was significantly higher than that for other outpatient health services and was observed primarily among low-income groups.

Public Dental Insurance

Although private dental insurance is clearly linked to greater dental utilization, the same trend does not exist with public dental insurance in the US where dental insurance primarily targets low-income children. The most common form of public dental insurance is Medicaid, which typically covers children through age of 20 years, although some limited dental coverage is often available for adults. Medicare for seniors does not include dental coverage. Most US states have found that both enrollment and utilization are both low for Medicaid dental insurance. Nationally, among the children without dental insurance, approximately 3 million are likely eligible for public insurance but had not enrolled. Among those enrolled, often only 20–30% of children actually receive dental care in a given year.

There are several reasons for the low utilization rates. A major hindrance to utilization is that reimbursement rates for dentists serving Medicaid recipients is significantly below usual and customary dental fees in most states, reducing the number of dentists willing to accept Medicaid patients. Dentists also cite administrative difficulties (prior authorization and eligibility verification) and an excessive number of broken appointments as reasons for not accepting Medicaid patients. In fact, Medicaid utilization rates are typically not related to the absolute number of dentists in a county, but rather to the number of dentists accepting Medicaid patients. This suggests that simply increasing the number of providers may not be sufficient to increase use of dental services in underserved areas.

Some states have developed innovative Medicaid programs that have dramatically increased utilization rates. For example, in 2000, Michigan implemented a Medicaid program, Healthy Kids Dental, where in select counties a private insurance carrier, Delta Dental, administered the program and reimbursed dentists at the private rate. The results of the program were to increase utilization by 31.4% overall and 39% among continuously enrolled children. Furthermore, the program resulted in a substantial increase in dental participation and a decline in the distance between providers and the children receiving care.

Time Costs

Beyond the direct monetary costs of dental care, there are also indirect costs to seeking care such as the time spent traveling to care and waiting on service. The empirical evidence on the importance of these costs is inconclusive and measuring the effects is complicated by the fact that individuals often bundle their purchases of dental services with other goods and services, and that provider prices may vary in response to expected wait times. Furthermore, wages, which are the opportunity cost of visiting a provider during working hours, tend to be lower in rural areas. As a result, the cost of the extra travel time is at least partially offset by the lower opportunity cost of time.

Other Variables

Money is not the only determinant of the demand for dental services. Dental anxiety may curtail demand for some individuals. Educational achievement probably affects awareness of the benefits of dental care and may make it possible to lower the costs of obtaining dental care. As one would expect, an immediate need for care as measured by presence of tooth pain or gum bleeding has been found to be associated with a greater likelihood of seeking care. Less obviously, a very low state of dental health may actually lower an individual’s need for care. Although poorer quality dentition on average might indicate greater need for care, lost teeth no longer need preventive care and costly restoration procedures over an individual’s lifetime. This is one reason why studies investigating the effect of community water fluoridation on dental demand have been inconclusive. Although fluoridation is effective in reducing decay, it results in the retention of more teeth over a lifetime, which could increase the need for care during a person’s life.

Determinants Of Dental Service Supply

Roughly speaking, the supply of dental services can usefully be broken down into three parts: the supply of dental professionals, the hours those professionals choose to work, and the mix of services offered by dentists, hygienists, and auxiliaries. In the short run, supply of all trained dental professionals and the mix of services offered by each type of professional is relatively fixed. It takes time to gain the required education and begin practicing, and the service mix is largely determined by state licensing regulations. The third factor, hours worked, can respond relatively rapidly to changes in wages.

Dentist Profession

The chief dental care provider is a dentist. Typically, industrialized countries require a dental degree from a university to become a licensed dentist. In the US, entry into the profession requires a graduate degree consisting of four years of training leading to a Doctor of Dental Surgery degree or the equivalent Doctor of Dental Medicine degree. The first two years include basic medical and dental science and the second two years focus on clinical training. In many other countries, a dental degree is provided as a bachelor’s degree program.

Graduates of accredited dentistry programs in most countries must also obtain a license to practice dentistry. In the US and Canada, graduates must pass a national licensure board exam and meet other state or province licensure requirements in order to practice. European countries, alternatively, permit free movement within the European Economic Area once a dentist is licensed to practice. However, other restrictions, such as the ability to treat patients participating in Germany’s sickness funds, limit the mobility of dentists.

Dental schools and many other institutions (generally, universities with medical schools, or large hospitals) offer advanced education programs of one to six years duration that train dentists to provide better quality clinical care or specialty care such as endodontics, periodontics, orthodontics, prosthodontics, and oral/maxillofacial surgery.

Supply Of Dentists

Supply Over Time

Higher wages may induce fairly rapid changes in the supply of dentists’ services as some dentists postpone retirement or work more hours. However, higher wages could also induce some dentists to work fewer hours, choosing to substitute leisure for work, a phenomenon referred to by economists as a backward-bending labor supply curve because increasing wages have the unexpected effect of reducing the amount of work people are willing to provide. Among dentists in the US, this choice to work less as wages rise may in fact be occurring at the margin. Dentists work, on average, far fewer hours than physicians. Therefore, higher wages could actually reduce the amount of services available. In the long run, expanding the number of licensed dentists will require an expansion of the number of spaces available in dental schools either through expansion of existing schools or the building of new ones.

It is interesting to note that, if dentists are indeed on the backward-bending portion of their supply curve, then increasing the supply of dentists has a larger effect on the supply of dental services than it does on the supply of dentists. Insofar as the added dental graduates drive dentist wages down, then, on average, already licensed dentists will expand their hours. In this way, each new graduate increases the supply of dental services by more than their own contribution of hours to the labor force.

In estimating the supply of dentists needed in the coming years, changes in productivity should also be taken into account. Since 1960, there have been significant fluctuations in productivity, ranging from an increase of 3.95% annually from 1960 to 1974, 0.13% annually from 1974 to 1991, and 1.05% growth annually from 1991 to 1998. The first increase was due to the use of high-speed drills and more auxiliary labor, whereas the 1991–98 increase was likely due to general economic expansion and the further increase in auxiliary employment.

The composition of the dentist workforce can also influence the supply of services. Studies have found differences in hours worked between male and female dentists, as well as differences by the age of the dentist. Older dentists, particularly males, worked fewer hours. Having children reduced the hours work among female dentists. Men and women are equally productive on a per hour basis, but women work part-time twice as often, at least up through age 45.

Internationally, the dentist-to-population ratio varies significantly. Low-income countries tend to have very low dentist to population ratios. In Africa, for example, the dentist-to-population ratio is 1:150 000 compared to 1:2000 in most industrialized countries. Furthermore, most dentists are located in big cities, resulting in even lower dentist-to-population ratios in rural areas.

However, simply increasing the number of dentists may not solve the problem. Between 1985 and 1998, the number of dentists in Syria increased from 2000 to 11 000, resulting in a ratio of 1:1500 dentists per population. The Care Index (F/DMFT 100%) of the child population remained unchanged and adults only increased from 17% to 33%. Similarly, in the Philippines the dentist-to-population ratio is similar to high-income countries at 1:5000, but the Care Index of children remains very low. The likely explanation is that the majority of the population cannot afford restorative work even when dentists are available.

Licensure And Regulation

Occupational licensure has been shown to be an important source of variation among US states in the supply of dentists, other dental professionals, and dental services. Each state sets its own licensure requirements for both new dentists and for those moving into the state. Licensed dentists who wish to move to a new state must obtain a license in that state. This process can be facilitated if states have reciprocity agreements in which state dental licensing agencies agree to recognize the validity of each other’s license, or if they have licensure by credential in which states will grant licenses to practicing dentists who have met certain criteria, such as being in continuous practice for a specified period of time.

There are both benefits and costs to occupational licensure. On the one hand, licensure is intended to reduce uncertainty for consumers by ensuring a minimum level of competency or through greater standardization in care. On the other hand, licensing may increase cost and reduce supply by limiting entry into a market. It could also potentially reduce quality by screening out the most qualified individuals. Individuals with a high opportunity cost of time may opt not to enter a profession because of the high cost of obtaining a license.

Licensure generally does not have a significant direct effect on the quality of oral health outcomes, but can influence prices and the supply of dentists. For example, dental records from US Air Force enlistees reveals that stricter regulation has no effect on overall quality of outcomes. Restrictive licensing does, however, raise prices for consumers and earnings for dentists. A state that increased from low or medium to high restrictiveness could expect an 11% increase in the price of dental services. State-mandated restrictions on the number of branches of a dental practice and on the use of dental hygienists also results in higher prices.

Distribution Of Dentists Within US States

Where dentists settle within the US depends in large part on the size of the state’s population and the state’s per capita income, both of which are correlated with the per capita number of dental providers. Within the health care sector overall, there is virtually no relationship between the state of degree production and employment. Rather, the production of advanced degrees tends to be concentrated in large, densely populated states, and providers disperse across the country after degree completion. Often, however, providers do return to their home state after degree completion.

A separate issue from the total number of dentists in a state is how they are distributed within the state. The distribution of providers within states and the decision to locate to rural and/ or underserved areas has been studied more thoroughly in the context of physicians than dentists, although many of the findings can be applied to the dental profession. For medical students, having a rural upbringing and specialty preferences for rural practice mattered. For medical schools, a commitment to rural curriculum and rotations were the most significant factors in encouraging graduates to locate in rural areas. Similar results were found when UCLA/Drew Medical Education Program students participated in medical rotations in South Los Angeles, an impoverished urban area. After 10 years, 53% of graduates were located in an impoverished or rural area, compared with 26% of other UCLA graduates, even after controlling for race and ethnicity.

Applying these results to dental education, a recent national demonstration project involving 15 schools established goals of increasing senior students’ time providing care to underserved patients, educating students to treat underserved populations and expanding enrollment of underrepresented minorities. Results reveal that the quantity of time spent in community settings increased from 10 to 50 days, the participating schools developed courses in cultural competency and public health, and underrepresented minority enrollment increased. However, support from a government sponsored loan repayment program was the most significant predictor of plans to go into public service. Alternatively, increasing educational debt was the most significant barrier to public service plans.

Dental Auxiliaries And Other Providers Of Oral Health Services

Types Of Oral Health Providers

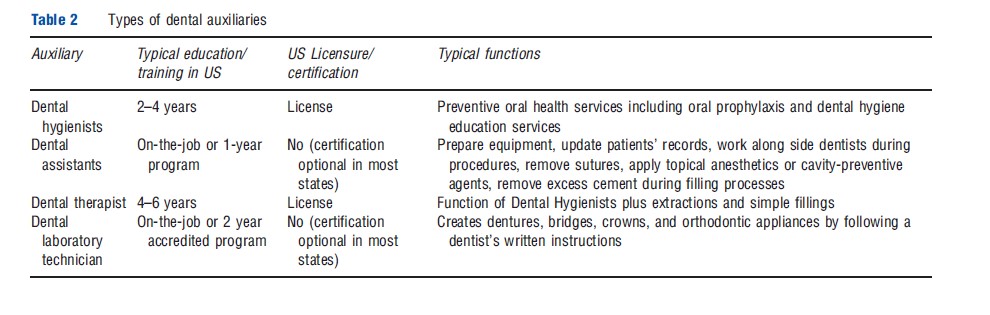

In addition to dentists, there are a variety of dental auxiliaries and other health professionals that provide oral health services. They include dental hygienists, dental assistants, dental therapists, and dental laboratory technicians. Regulations, training requirements, and the specific functions performed by each auxiliary type varies from country to country, and not every country licenses each type of auxiliary. Table 2 summarizes the training, licensure, or certification typically required, and the functions typically performed by dental auxiliaries found in the US. Dental hygienists focus on preventative care. Dental assistants provide more direct aid, working alongside the dentist. Most states have enacted provisions to permit dental assistants to conduct more tasks after obtaining additional certification.

Dental therapists are less widespread in the US. As of 2011, only Minnesota and some remote parts of Alaska permitted dental therapists. The safety and effectiveness of dental therapists tend to be high. In Alaska, dental therapists exercise good judgment, provide appropriate care, and have highly satisfied patients.

In contrast, dental therapist is a well-established profession in a number of countries. In New Zealand, where dental therapy began in 1921, dental therapists focus on children. The result is more than 60% of children from 2 to 4 years old utilize public oral health services, with an average cost of US $99 the per child. Currently, there are at least 54 countries that use dental therapists, most often staffing school-based programs.

Beyond these standard auxiliaries, individuals may receive oral health care from other providers. Primary care physicians, for example, can be involved early in oral health through a number of possible interventions including screening, counseling, referral to dentists, application of fluoride varnish, and the provision of supplemental fluoride. However, many pediatricians are not actively providing oral health services. More than 90% of pediatricians said that they should examine teeth for caries and educate families, but only 54% did so for more than one-half of their patients between the ages of zero and three. Only 4% of pediatricians regularly applied fluoride varnish. The most common barrier is lack of training.

Regulation Of Dental Hygienists

The experience of the dental hygiene profession in the US illustrates the potentially negative effects of restrictive licensure practices for dental auxiliaries. In the US, state dental boards are typically responsible for regulating the dental hygiene profession, making dental hygiene the only licensed profession regulated by another profession. States vary significantly in both their entry requirements, including what is required to obtain a licensure by credentials, and in their scope of practice restrictions, which range from allowing only basic teeth cleaning and polishing services to conducting more complex or potentially hazardous procedures such as administering anesthesia and conducting restorative functions. States also regulate the level of supervision required by dentists, ranging from direct supervision to complete autonomy.

The consequence of restrictive scope of practice regulations is to increase the demand for dentists, while underutilizing hygienists. The US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) estimated that the price effects of state-imposed restrictions on the number of dental auxiliaries that dentists are permitted to employ or the functions hygienists can perform resulted in a 7–11% increase in prices, which cost consumers approximately $700 million in 1982. In 2003, the FTC issued a complaint against the South Carolina Dental Board for prohibiting hygienists from providing teeth cleaning services to Medicaid children. The case was eventually settled. The restrictions dentists have placed on hygienists suggest that dentists view expanded dental hygiene services as a substitute for dental services. What the evidence suggests is that hygienists may also serve as a complement to dentists allowing dentists to specialize in more complex procedures.

The consequence of regulations restricting the use of hygienists and other mid-level providers is often to eliminate the lower cost, lower quality segment of the market. The elimination of the lower cost market segment is troubling when it serves to prevent lower income individuals from purchasing important services and simply forgo treatment that would improve health outcomes. Researchers have found a correlation between restrictive dental hygiene regulations and dental hygienist salaries, dental office visits, hygienist employment levels and, ultimately, access to oral health care.

Conclusion

Oral health has generally been improving in industrialized countries, along with increased utilization and per capita spending on dental care. However, the US experience illustrates that such improvements can occur while significant disparities persist. Tooth decay continues to be a major problem among its low-income, rural, and minority populations. The trend goes the opposite direction for low-income countries where the prevalence of dental caries is increasing from previously low levels because of the adoption of developed nation diets without the corresponding dental care infrastructure.

There are both economic and medical consequences of poor oral health, yet the solutions for improving oral health outcomes are far from clear. Insurance and income are both strong predictors of demand for dental services, but as the US illustrates low reimbursement rates and administrative difficulties can render public insurance for low-income individuals less effective at raising utilization rates. The availability of oral health services is likely to increase in the coming decades. If the international pattern follows that of developed countries, the supply of dentists is likely to increase with rising incomes and greater need in developing countries in the coming decades. Dental auxiliaries and other oral health providers may also play an increasingly important role in the provision of dental services as oral health systems modernize. Without adequately funded and managed public programs to target disadvantaged populations and prudent consumer-friendly regulations, much of this increase in dental service will bypass many of those most in need.

References:

- Baelum, V., Van Palenstein Helderman, W., Hugoson, A. and Yee, R. (2007). A global perspective on changes in the burden of caries and periodontitis: implications for dentistry. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation 34, 872–906.

- Beazoglou, T., Heffley, D., Brown, L. J. and Bailit, H. (2002). The importance of productivity in estimating need for dentists. Journal of the American Dental Association 133(10), 1399–1404.

- Dye, B. A., Tan, S., Smith, V., et al. (2007). Trends in oral health status: United States, 1988–1994 and 1999–2004. Vital and Health Statistics 11(248), 1–92.

- Glied, S. and Matthew, N. (2010). The economic value of teeth. Journal of Human Resources 45(2), 468–496.

- Kleiner, M. M. (2006). Licensing occupations: ensuring quality or restricting competition? Upjohn Institute.

- Kleiner, M. M. and Kudrle, R. T. (2000). Does regulation affect economic outcomes?: The case of dentistry. The Journal of Law and Economics 43(2), 547–582.

- Lewis, C. W., Boulter, S., Keels, M. A., et al. (2009). Oral health and pediatricians: Results of a national survey. Academic Pediatrics 9(6), 457–561.

- Liang, J. N. and Ogur, J. (1987). Restrictions on dental auxiliaries. Washington, DC: Federal Trade Commission.

- Petersen, P. E., Bourgeois, D., Ogawa, H., Estupinan-Day, S. and Ndiaye, C. (2005). The global burden of oral diseases and risks to oral health. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 83(9), 661–669.

- Skillman, S. M., Doescher, M. P., Mouradian, W. E. and Diane, K. B. (2010). The challenge to delivering oral health services in rural America. Journal of Public Health Dentistry 70(Suppl. s1), S49–S57.

- S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) (2000). Oral health in America: A report of the Surgeon General. Rockville. MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health. Available at: http://www.surgeon general.gov/library/oralhealth/ (accessed 29.04.11).

- Wanchek, T. (2010). Dental hygiene regulation and access to oral healthcare: assessing the variation across the U.S. states. British Journal of Industrial Relations 48(4), 706–725.

- Wing, P., Langelier, M., Continelli, T. and Battrell, A. (2005). A dental hygiene professional practice index (DHPPI) and access to oral health status and service use in the United States. Journal of Dental Hygiene 79, 10–20.

- World Health Organization (2001). Global oral health data bank. Geneva: World Health Organization.