Many developed countries require occupational licenses for everyone from surgeons to interior decorators. Licensing in effect creates a regulatory barrier to entry into licensed occupations, and thus results in higher income for those with licenses. However, licensing is assumed to protect the public interest by keeping incompetent and unscrupulous individuals from working with the public. According to data collected in a 2008 national survey of the US workforce, 76% of all nonphysician medical occupations were licensed, the highest among all occupations in the survey conducted by the Krueger (2008). The goal of this article is to outline the major tensions between the monopoly face of licensing and the consumer protection face of occupational regulation in the health care industry. To do this, a theory of licensing is presented, which includes how it is used and some of the controversies surrounding its implementation, and the limited empirical results examining its effectiveness in enhancing quality or restricting competition.

To distinguish various forms of regulation, licensing, certification, and registration is defined below.

- Licensing: Licensing refers to situations in which it is unlawful to carry out a specified range of activities for pay without first having obtained a license. This confirms that the license holder meets prescribed standards of competence. Workers who require such licenses to practice include doctors, lawyers, and nurses.

- Certification: Certification refers to situations in which there are no restrictions on the right to practice in an occupation, but job holders may voluntarily apply to be certified as competent by a state-appointed regulatory body. Two examples of certification would be a certified financial analyst or a certified respiratory therapist.

- Registration: Registration refers to situations in which one can register one’s name and address and qualifications with the appropriate regulatory body. Registration provides a standard for being on the list, but complaints from consumers or improper listing of credentials can result in removal from the list.

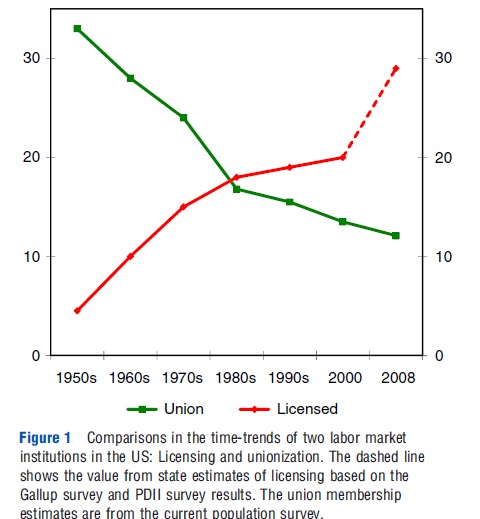

Licensing has been among the fastest growing labor market institutions in the US. Figure 1 shows the growth of occupational licensing relative to the decline of union membership since the 1950s. By 2008, occupational licensing in the US had grown to 29% of the workforce, up from below 5% in the 1950s. In contrast, unions represented as much as 33% of the US workforce in the 1950s, but declined to less than 12% of the US workforce by 2008. Much of this change was because of the shift from manufacturing employment to service sector employment such as medical services (e.g., nurses), where unions have continued to grow.

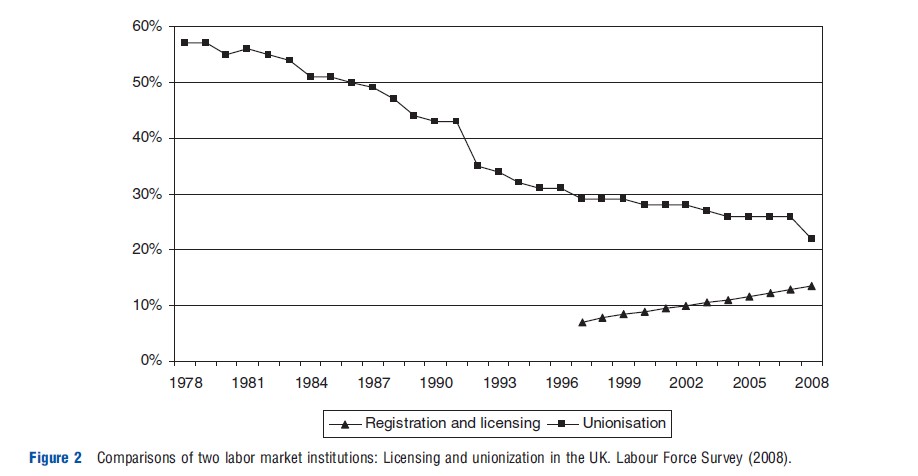

A similar trend exists for the UK with declining unionization trends, but growth in occupational licensing. Figure 2 shows that these trends in UK for the period 1978–2008 are consistent with the US trend line. In contrast to the US, approximately 14% of the UK workforce are licensed, but only approximately 22% belong to unions (Hummphris et al., 2011). The data were compiled from the British Labour Force Survey for both unions and licensed occupations. With the growth in the service industries, the percentage of the workforce in licensed occupations appears to be rising in the UK.

The Theories Of Occupational Licensing

Here, the evolution of theories of occupational licensing is reviewed, ranging from the mechanistic ones to those that utilize human capital theory. It begins by outlining the simplest theory of occupational licensing, which draws more heavily on administrative procedures than on economics. Insights from more complex theoretical models is then incorporated that challenge some of the straightforward assumptions of the simple theory and which thereby provide richer insights into the operation and effects of regulation.

An Administrative Theory Of Licensing

A simple theory of occupational licensing envisions a costless supply of unbiased, capable gatekeepers and enforcers. The gatekeepers screen entrants to the occupation, barring those whose skills or character suggest a tendency toward low-quality output. The enforcers monitor incumbents and discipline those whose performance is below standard with punishments that may include revocation of the license needed to practice. Assuming that entry and performance are controlled in these ways, the quality of service in the profession will almost automatically be maintained at or kept above standards that are set by the gatekeeper to the profession. Within this approach only those who have the funds to invest in training and the ability to do the work are able to enter the occupation.

Introducing economics to this otherwise mechanical model by noting that a key discipline on incumbents – the threat of revoking one’s license – may not mean much if incumbents can easily re-enter the profession, such as by moving to a new firm, or by shifting to an alternative occupation with little loss of income. Because grandfathering (i.e., allowing current workers to bypass the new requirements) is the norm when occupations seek to become licensed, incumbent workers are usually supportive of the regulation process. In the absence of grandfathering, lower skilled workers in the occupation may have to seek alternative employment. For example, if sales skills are the key to both providing licensed sales of heart monitors and the nonlicensed selling of shoes or cars, then individuals may shift between these lines of work with little loss of income.

Under these circumstances, meaningful discipline for license holders may require deliberate steps to ensure that loss of license entails significant financial loss. Such additional steps could include imposition of fines, improved screening to prevent expelled practitioners from re-entering the occupation, or requiring all incumbents to put up capital that would be forfeited upon loss of the license. To offset the possibility that incumbents could shift to other occupations with little loss of income, entry requirements could be tightened to limit supply and create monopoly rents within the licensed occupation. The threat of losing these monopoly rents could, in principle, give incentives to incumbents to maintain quality standards. This may also result in some increases in human capital investments in order to attain the additional requirements. The rents could also motivate potential entrants to invest in high levels of training in order to gain admittance. This suggests that licensing can raise quality within an industry by restricting supply, raising labor wages and output prices. Increasing prices may signal either enhanced quality because of perceived or actual skill enhancements or restrictions on the supply of regulated workers.

State-regulated occupations can use political institutions to restrict supply and raise the wages of licensed practitioners. This is assumed to be a once-and-for-all income gain that accrues to current members of the occupation who are ‘grandfathered’ in, and do not have to meet the newly established standards (Perloff, 1980). Generally, workers who are ‘grandfathered’ are not required to ever meet the standards of the new entrants. Individuals who attempt to enter the occupation in the future will need to balance the economic rents of the field’s increased monopoly power against the greater difficulty of meeting the entrance requirements.

Once an occupation is regulated, members of that occupation in a geographic or political jurisdiction can implement tougher statutes or examination pass rates and may gain relative to those who have easier requirements by further restricting the supply of labor and obtaining economic rents for incumbents. Restrictions would include lowering the pass rate on licensing exams, imposing higher general and specific requirements, and implementing tougher residency requirements that limit new arrivals in the area from qualifying for a license. Moreover, individuals who have finished schooling in the occupation may decide not to go to a particular political jurisdiction where the pass rate is low because both the economic and shame costs may be high.

One additional effect of licensing is that individuals who are not allowed to practice at all in an occupation as a consequence of regulation may then enter a nonlicensed occupation, shifting the supply curve outward and driving down wages in these unregulated occupations. If licensing requirements contain elements of required general human capital, then it is possible that these workers may raise the average skill level in their new occupation.

Applications To Health Care

Standard economic theory of the effects of occupational licensing regulations on prices and quantities in the health care industry begins with the analysis of Friedman and Kuznets (1945) and Friedman (1962). In this line of reasoning, licenses act as a barrier to entry that can restrict supply and increase wages and other prices relative to a counterfactual competitive market. By contrast, paternalistic arguments and the existence of asymmetric information favor regulating health service providers. The issue is that because providers (e.g., physicians, nurses and physical therapists) may know more about a patient’s health condition and the available treatment options, consumers may unwittingly receive low-quality care and possibly that this low-quality care will have larger and sometimes irreversible consequences. Governments might fear that by allowing ‘lower skill’ providers – such as nurses relative to doctors – to provide health services they may be exposing consumers to increased risk. In some situations the risks could also impose externalities: for instance, if low-skill health providers increase the transmission of an infectious disease then there might be a case for regulation. This raises two issues. One is that a paternalistic regulator might want to increase the quality of care received in the market. Another is that a regulator might want to ensure that providers have a minimum level of competency to minimize the negative consequences of asymmetric information. Both of these issues are supported by evidence and analysis.

A major argument for the licensing of medical occupations is that it eliminates or reduces the patient’s health risk of seeking the services from an occupation. If testing and background checks ‘eliminate charlatans, incompetents, or frauds’ (Council of State Governments, 1952), then consumers may be willing to pay a higher price for the services offered by the regulated occupation. A review of the body of theory from experimental economics and psychology shows that consumers value the reduction in downside risk more than they value the benefits of a positive outcome (Kahneman et al., 1991). This preference by consumers for the status quo or reducing the risk of a highly negative outcome has been called ‘loss aversion,’ which is an element of prospect theory developed by Kahneman and Tversky (1979). For example, as discussed earlier, social welfare may be increased substantially by minimizing the likelihood of a poor diagnosis as a consequence of going to an incompetent physician, because the incompetent physicians have been weeded out as a result of licensing. Consequently, licensing may also reduce patients’ perceived benefits of receiving nonstandard but potentially highly effective treatment from an unlicensed practitioner of traditional medicine. Using the power of the state to both limit the downside risk of poor quality care and reduce the possibility of an upside benefit may be a trade-off that maximizes consumer utility or welfare. Evidence of the acceptance of this trade-off can be found in the growth of occupational licensing during the past century across virtually all nations that have been studied.

The gains from an unregulated service can be potential benefits from free market competition of lower prices and greater innovation without the constraints of a regulatory body, such as a licensing board. This upside potential gain can be achieved through both the use of nonstandard methods or new research that has not been approved by the licensing agency as appropriate for the service (Rottenberg, 1980). Deviations from the prescribed methods of providing a service are discouraged by licensing boards, and may even be found to be illegal. For example, not having a dentist on site is illegal in the US when providing a service such as teeth cleaning. Dental hygienists generally are not allowed to ‘practice’ without a dentist on site, with the ‘site’ being defined by statute or the dental board. In addition, dental hygienists are not allowed to open offices to compete with dentists. Although this policy reduces the chance that a dental hygienist will fail to find a major disease that may require immediate attention, it also reduces the ability of the hygienist to provide the limited services that particular patients require. Moreover, there is little leeway for the dental service industry to provide new or innovative services without the risk being found in violation of the licensing laws. The licensing laws give rise to the labor relations concept of ‘featherbedding,’ whereby dentists are on the premises – but do little work.

Consequently, regulation through licensing medical services can be the equivalent of a closed shop in unionized markets. Theoretically, higher wages are likely to result from restricted labor supply. Because closed shops in unionized markets are illegal in both the US and the UK, it is interesting that, with respect to organized labor markets, the equivalents of closed shops are nevertheless permitted in licensed occupations.

Illustrations In Medical Markets

One illustration of the potential outcome of licensing in medical markets is presented by the Nobel laureate economist Milton Friedman. Consistent with his work cited earlier in this section, he finds licensing to have an overall negative influence for consumers. The argument can be found on YouTube as follows (Milton Friedman – Health Care in a Free Market, YouTube video, 9:03, from a question-and-answer session with medical professionals at the Mayo Clinic in 1978, posted by ‘LibertyPen,’ 25 September 2009): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-6t-R3pWrRw – Milton Friedman

Further illustrations of the influence of licensing on markets can be found in commercial media as well. For example, libertarian commentator John Stossel poses additional questions regarding the value of licensing in an excerpt from his television show that featured several episodes on occupational regulation (‘Stossel Show – Licensing! (Part 1/6),’ YouTube video, 9:43 (part 1), posted by ‘TheChannelOfLiberty,’ 17 March 2010). The excerpt on YouTube, at the link below, serves as an overarching illustration of the influence of licensing on labor and consumer markets: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v ¼ f0JGu4tlmmk – The Stossel Show – Licensing

On a more practical basis, however, the entry requirements for many health care occupations are often presented as including the requirement for being licensed, as illustrated in another YouTube video (‘How to Get Medical Jobs: How to Become an Occupational Therapist,’ YouTube video, 0:50, posted by ‘expertvillage,’ 26 September 2008): http://www.youtube.com/watchv=GM9ohB2qyQM

As with many occupations in the health care field, the requirements for being licensed are becoming more stringent. For example, the requirement for becoming a physical therapist in the US has increased within the past 5 years from 2 years of post-high school training to requiring a doctor of physical therapy in order to conduct many of the required tasks.

Empirical Evidence In Licensed Health Care Markets

The initial empirical work in medical markets was based on data from the 1930s. The classic and often cited study completed through the National Bureau of Economic Research by Nobel Prize-winning economists Milton Friedman and Simon Kuznets estimated that the 33% earnings premium of physicians relative to dentists could be attributed to more than just 1 year’s difference between the requirements to become a doctor versus a dentist (Friedman and Kuznets, 1945). They estimate that the difference in earnings between doctors and dentists should be approximately 17% based on human capital and other observable factors, but that the additional 16% residual gap is in large part a consequence of physicians’ greater ability to restrict labor supply. Milton Friedman’s book, Capitalism and Freedom, argues that physicians were able to obtain substantial earnings gains over dentists during the 1920s and 1930s because they were able to limit new student enrollment in medical school (Friedman, 1962). More recently, however, a reversal of these trends has taken place.

During a relatively recent period of time (1990–2000), the number of new physicians increased by almost 22% (Public Use Sample, US Census, 2000). In contrast, the total number of dentists during the same period of time decreased. Dental school enrollment increased by only 1% each year during the 1990s, and the number of dentists in the US declined by almost 2% over the decade as a result of both retirements and individuals leaving the occupation (Public Use Sample, US Census, 2000).

A more general review of empirical research on licensing (in the US?) found that licensing is associated with consumer prices that are 4–35% higher than those found among unlicensed occupations, depending on the type of commercial practice and location (Kleiner, 2006). Kleiner and Kudrle (2000), for example, found that tougher state-level restrictions and more rigorous pass rates for dentists were associated with hourly wage rates that were 15% higher than in states with few restrictions, with no measurable increase in observable health benefits.

Occupational licensing appears to increase wages in several nations in the European Union (EU), but the estimates usually are lower than in the US. In the EU nations with greater overall wage disparities, such as in the UK, wages in the licensed occupations of medical practitioners, pharmacists, pharmacologists, and dental practitioners were an estimated 6–65% higher than otherwise similar workers in unlicensed occupations (Kleiner, 2006). In contrast, physicians and dentists in France earn an estimated 8–21% more than their unlicensed colleagues, whereas workers in those professions in Germany, which has lower overall wage disparities, have similar wages relative to unlicensed occupations.

In Europe, according to Dubois et al. (2006), a recent trend in the case of medicine and allied professions has been a shift from a system of self-governance that has traditionally granted professional associations’ disproportionate power in setting and monitoring standard toward one that grants the state more influence in the process.

Given the high level of licensing within the health care occupations, it is not surprising to find that one of the evolving issues is the question of who is responsible for tasks, and how the government determines the market. For example, dentists control the market for dental care and in most US states dental hygienists must work for a dentist and cannot open their own establishments (Kleiner and Park, 2010). The result is that in those few US states that allow hygienists to open their own offices they make approximately 10% more and have faster employment growth relative to hygienists in more restrictive states.

A complementary study by Wanchek (2010) found that using a detailed dental hygiene professional practice index and a simultaneous equation approach to reduce the potential influence of endogeneity of wages and employment, entry requirements are negatively correlated with dental hygienists’ employment and that practice restrictions that limit hygienists’ ability to do tasks within the dental office are negatively correlated with their wages. Higher wages and lower employment of hygienists both reduce access to care, as observed in the prevalence of dental office visits. Finally, the author finds that the results are consistent with a state’s entry and practice regulations jointly affecting access to oral healthcare.

Similarly, for nurses and doctors, in those US states that allow nurses to do simple procedures, such as ‘well-baby’ exams without the supervision of a physician, health insurance spending is approximately 10% lower (Kleiner et al., 2012) than in more restrictive states with no apparent influence on the quality of health care. Licensing not only influences wages and prices relative to unregulated situations, but also influences wages and prices across regulated occupations.

Kyoung-Hee Yu and Frank Levy (2010) examined the reasons why one might expect it to be more difficult to do offshore licensed professional work than manufacturing work in a globalized world. The authors conduct numerous interviews and provide data on a specific case: the offshoring of diagnostic radiology from the US, the UK, and Singapore, and find that regulation of the occupations matters. As far as professional services in healthcare are concerned then, institutional barriers are real and useful for the professions in terms of restricting entry. To the extent that institutional frameworks differ across nations, globally integrated markets have yet to emerge for professional services in healthcare.

Conclusions

Licensing can in effect create a regulatory barrier to entry into licensed occupations, and thus results in higher income for those with licenses. Although more research is needed for a definitive answer, preliminary evidence points to licensing raising wages and prices in health care, but with no clear influence on the quality of care or with a clear impact on downside outcomes such as hospital readmissions, repeat visits to a health care professional, or deaths due to incompetent or unscrupulous purveyors of health care services. More detailed analysis using experimental data and field experiments with elements of random assignment would enhance the ability to make policy recommendations regarding the licensing of health care occupations.

References:

- Council of State Governments (1952). Occupational Licensing Legislation in the States. Chicago: Council of State Governments.

- Dubois, C. A., Dixon, A. and McKee, M. (2006). Reshaping the regulation of the workforce in european health care systems. In Dubois, C. A. (ed.) Human resources for health in Europe, pp. 173–192. Berkshire: WHO – Open University Press.

- Friedman, M. (1962). Capitalism and freedom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Friedman, M. and Kuznets, S. (1945). Income from independent professional practice. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Hummphris, A., Kleiner, M. and Koumenta, M. (2011). How does government regulate occupations in the UK and US? Issues and policy implications. In Marsden, D. (ed.) Employment in the lean years. Policy and prospects for the next decade, pp. 87–101. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. and Thaler, R. (1991). The endowment effect, loss aversion, and status quo bias. Journal of Economic Perspectives 5(1), 193–206.

- Kahneman, D. and Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometrica 47(2), 263–292.

- Kleiner, M. (2006). Licensing occupations: ensuring quality or restricting competition? Michigan: W.E. Upjohn Institute.

- Kleiner, M. and Kudrle, R. (2000). Does regulation affect economic outcomes? The case of dentistry. Journal of Law and Economics 43(2), 547–582.

- Kleiner, M., Mairer, A., Park, K. W. and Wing, C. (2012). ‘Relaxing Occupational Licensing Requirements: Analyzing Wages and Prices for a Medical Service,’ Working Paper, Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota.

- Kleiner, M., and Park K. (2010). ‘Battles Among Licensed Occupations: Analyzing Government Regulations on Labor Market Outcomes for Dentists and Hygienists.’ NBER Working Paper 16560. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Krueger, A. B. (2008). Princeton Data Improvement Initiative (PDII), Conference Report. Princeton, New Jersey: Trustees of Princeton University.

- Perloff, J. (1980). The impact of licensing laws on wage changes in the construction industry. Journal of Law and Economics 23(2), 409–428.

- Princeton Data Improvement Initiative (2008). Princeton University.

- Rottenberg, S. (1980). Introduction. Occupational Licensure and Regulation, pp. 1–13. Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute.

- US Census 5-Percent Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS) Files (2000).

- Wanchek, T. (2010). Dental hygiene regulation and access to oral healthcare: Assessing the variation across the US states. British Journal of Industrial Relations 48(4), 706–725.

- Yu, K. H. and Levy, F. (2010). Offshoring professional services: Institutions and professional control. British Journal of Industrial Relations 48(4), 758–783.

- Kleiner, M. and Krueger, A. (2010). The prevalence and effects of occupational licensing. British Journal of Industrial Relations 48(4), 676–687.

- Kleiner, M. M. and Krueger, A. B. (2013). Analyzing the extent and influence of occupational licensing on the labor market. Journal of Labor Economics S173–S202.