Since the 1990s an increasing number of European countries permit periodic consumer choice of insurer in their social health insurance schemes (e.g., Belgium, the Czech Republic, Germany, Israel, the Netherlands, Russia, Slovakia, Switzerland, and Russia). It can be hypothesized that such consumer choice provides the insurers with effective incentives for efficiency and innovation. However, an unregulated competitive health insurance market also tends toward risk-adjusted premiums and rejection by insurers of high-risk applicants. Therefore, governments in these countries interfered with regulation to make health insurance accessible and affordable for everyone. Risk-adjusted equalization payments are a necessary component of any efficient intervention. Other potential interventions have unfavorable effects: premium regulation creates incentives for selection (which may have several unfavorable effects) and expost compensations to the insurers reduce their incentives for efficiency. However, because risk equalization is technically complex, policymakers are confronted with a complicated trade-off between affordability, selection and efficiency.

Risk equalization is discussed from a European perspective. First its relevance is discussed in the competitive health insurance markets and some technical complications (Section ‘Why Risk Equalization, and How?’). Then a historical perspective of the European experience with risk equalization (Section ‘The European Experience with Risk Equalization: A Historical Perspective’) and future perspectives including its relevance for provider payments and for countries with a National Health Service (NHS) such as England is provided. Finally the conclusions are summarized in the Section ‘Conclusion.’

Why Risk Equalization, And How?

The solidarity principle, which is highly valued in Europe, implies that high-risk and low-income individuals receive a subsidy to make health insurance affordable. Therefore a great challenge for policymakers is: how to combine solidarity with consumer choice of health insurer? In an unregulated competitive insurance market insurers have to break even, in expectation, on each contract, because competition minimizes the predictable profits per contract. Insurers can do so by (1) adjusting the premium to the consumer’s risk (premium differentiation), (2) adjusting the product, for example, coverage and benefits designed to attract different risk groups per product and charge premiums accordingly (product differentiation), or, if the transaction costs of further premium and product differentiation are too high, (3) by adjusting the accepted risk to the premium of a given product (risk selection), for example, by excluding certain preexisting medical conditions from coverage or by not accepting high-risk people. Given the average expenses per risk group, unregulated competition could result in premiums that can differ a factor of 500 or more once health status and age are taken into account.

Although premium differentiation makes coverage less affordable for the high risks, risk selection (by excluding certain preexisting medical conditions from coverage or by not accepting high-risk people) makes coverage less available to the high risks. In both ways, guaranteed access to affordable coverage for the high risks is jeopardized.

To simplify the analysis, it is assumed that health insurers are bound to an open enrollment requirement. This implies that insurers must accept each applicant for a standard coverage. In practice, open enrollment is required in all countries with a competitive social health insurance market. As long as insurers are free in setting premiums, this assumption is nonrestrictive, because insurers are allowed to risk-adjust the premium for each applicant and can offer each type of policy in addition to the policy with the standardized coverage. By this assumption the problem of unavailability that would occur in case of rejection or coverage restrictions, is essentially transformed into a problem of unaffordability (high premiums for high-risk individuals) to be solved by cross subsidies. In this article the author focuses only on the so-called risk-solidarity, i.e., cross subsidies from low-risk to high-risk individuals (and not on income solidarity).

An effective way to achieve risk-solidarity without disturbing competition among the insurers is to give the high-risk consumers a subsidy out of a solidarity fund that is filled with mandatory solidarity contributions from the low risks. Ideally these subsidies are risk-adjusted, i.e., the subsidy is adjusted for the risk factors that the insurers use. For practical reasons the subsidy can be given directly to the insurers. In a transparent competitive market, insurers are forced to reduce each consumer’s premium with the per capita subsidy they receive for this consumer. By giving risk-adjusted subsidies to the insurers the different risks that consumers represent for them are equalized. Therefore this way of organizing risk-adjusted subsidies is referred to as ‘risk equalization.’ In practice, all European countries that apply risk-adjusted subsidies do this in the form of risk equalization (see Section ‘The European Experience with Risk Equalization: A Historical Perspective’).

Sometimes the term risk adjustment is used rather than risk equalization. However, risk adjustment can also be applied to, for example, provider payments. The term risk equalization is used to denote the specific case of ‘risk-adjusted compensations to (the consumers via) the insurers.’

Complementary Strategies

Although sufficiently risk-adjusted equalization payments can be an effective strategy to guarantee affordable coverage in a competitive individual health insurance market, in practice the risk equalization payments are still insufficiently risk-adjusted (see below). Therefore, in addition government may implement one or more of the following strategies:

- A system of ex-post cost-based compensations to the insurers. For example, the insurers are fully or partly compensated by government for an individual’s expenses in excess of a certain annual threshold. These compensations will be reflected in premium reductions, in particular for the high risk-risk enrollees.

- Premium rate restrictions. An extreme form of premium rate restrictions is that the premiums must be community rated, i.e., insurers must charge the same out-of-pocket premium for the same product to each enrollee, independent of the enrollee’s risk. All European countries with a competitive social health insurance market require the out-of-pocket premiums to be community rated.

However, each of these additional strategies has substantial drawbacks, resulting in serious trade-offs.

Ex-post cost-based compensations are not optimal because they reduce the insurers’ incentive for efficiency resulting in an affordability-efficiency trade-off.

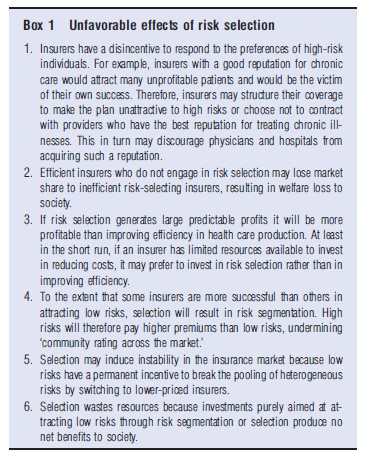

Premium rate restrictions have some major drawbacks as well. Although the goal is to create implicit cross subsidies from the low risks to the high risks who are in the same pool, this pooling creates predictable profits and losses for identifiable subgroups in the pool, and thereby provides insurers with incentives for risk selection, which may threaten affordability, efficiency, quality of care, and consumer satisfaction (see Box 1). Therefore, premium rate restrictions confront policymakers with an affordability-selection trade-off. In addition it is questionable to what extent premium rate restrictions are effective in the long term, because product differentiation may result in indirect premium differentiation. Insurers may offer special products for various risk groups, for example, depending on life-stage, lifestyle, or health status. Such risk segmentation across the product spectrum can be observed in, for example, Australia, Ireland, and South Africa, where premiums must be community rated. In this way ‘community rating per product’ results in low premiums for low risks and high premiums for high risks, which undermines the goal of ‘community rating across the market’.

Product differentiation may not only occur in voluntary health insurance markets, but also in mandatory social health insurance markets. For example, in the Netherlands a substantial variation in the health insurance products is allowed. These products may vary, for example, according to the list of contracted providers, the financial incentives to motivate consumers to use preferred providers, procedural conditions (e.g., yes or no preauthorization by the insurer or by the general practitioner) and the list of covered pharmaceuticals.

The relevance of good risk equalization is that if the equalization payments are sufficiently risk-adjusted (see below) there is no need for the other strategies, each of which confronts policymakers with severe trade-offs. The better the risk-adjusted equalization payments are adjusted for relevant risk factors, the less severe are these trade-offs.

Acceptable Costs; S-Type And N-Type Risk Factors

For the calculation of the risk-adjusted equalization payments it is important to determine the costs and the risk factors on which the payments should be based. The costs of the services and intensity of treatment that are acceptable to be compensated are denoted as the acceptable costs. For example, acceptable costs may be those generated in delivering a ‘specified basic benefit package’ containing only medically necessary and cost-effective care. Because the ‘acceptable cost level’ is hard to determine, in practice the equalization payments are mainly based on observed expenses rather than needs-based costs. However, observed expenses are determined by many factors, not all of which need to be used for calculating the equalization payments. Assume that all risks factors X that determine observed expenses can be divided into two subsets: those factors for which solidarity/subsidy is desired, the S-type factors; and those for which solidarity/subsidy is not desired, the N-type factors. Then the equalization payments should only be adjusted for the S-type risk factors and not for the N-type risk factors.

Decisions about which risk factors should be labeled an S-type or N-type factor, reflect value judgments that differ across countries and among individuals. In most societies health status and gender are likely to be S-type risk factors. Other risk factors may be open for discussion:

- Characteristics of the individual such as lifestyle, taste, income/wealth, religion, being self-employed, race, and ethnicity;

- Characteristics of the contracted providers, such as price level, practice style, utilization review, various health management strategies, and (in)efficiency;

- Characteristics of the region where the consumer is living, such as average price and income level, population density, average distance to hospitals, and whether there is an over-or undersupply of providers; and

- Characteristics of the contracts and financial incentives between plans and providers.

All European countries that apply risk equalization use age as a risk adjuster. This reflects the desired level of intergenerational solidarity and the desired way of paying health expenses over the life cycle in these countries. Nevertheless, age might (partly) be considered an N-type risk factor. Young people on average have relatively low health expenses and high expenses on housing, schooling and children, whereas for the elderly the opposite holds. The Affordable Care Act in the USA (‘Obamacare’) allows the insurers to differentiate their premium by a factor 1:3 for age for products sold via the so-called Exchanges, although the additional age-related variation in health expenses is compensated via risk equalization. In other words, age is partly an S-type risk factor and partly an N-type risk factor.

Region is often a disputable risk factor. It is likely that region captures differences in health status, which most likely are to be compensated. However, region also reflects differences in other risk factors, such as price level, oversupply, inefficiency, practice style, etc., which might not be compensated. The more health related risk factors are explicitly included in the equalization formula, the less will region reflect regional health differences and the more it will reflect regional differences in nonhealth factors.

If it is explicitly decided to adjust the equalization payments only for S-type risk factors and not for N-type risk factors, a logical consequence is that insurers are allowed to ask premiums from the consumers that are related to the Ntype risk factors. If not, the insurers have incentives for selection based on these risk factors.

If the equalization payments are based on observed expenses, as is mostly the case in practice, the calculation of the risk-adjusted equalization payments could be as follows. Assume that E(X) is the best estimate of the expected expenses in the next contract period for a person with risk characteristics X. An estimate of the acceptable cost level could then be E(X) with the values of the N-type risk factors set at an acceptable level (e.g., the acceptable level of the price or supply of health care or the acceptable practice style). Because some components of the vector X have been fixed at some specific value, the acceptable cost level can be written as a function that only depends on the nonfixed values. Hence if X = (Xs, Xn) and Xs has the S-type factors and Xn the N-type factors, then the acceptable cost level would be A(Xs). The risk-adjusted equalization payment could then be a function of A(Xs), for example, it could be A(Xs) minus a fixed amount Y (or a certain percentage of A(Xs), as in the USA Medicare). Negative equalization payments imply payments from the insurer to the subsidy fund. If it is assumed that the average premium (excluding surcharges for administration, selling costs, profits, etc.) equals the average predicted health expenses, the national average of the consumers’ out-of-pocket premiums (i.e., premium minus equalization payment) equals Y. In countries such as Russia and Israel, Y = 0. In these countries the consumers do not pay any out-of-pocket premiums directly to their insurer. In countries such as Switzerland and Ireland, Y equals the average predicted per capita expenses. The Netherlands has an intermediate position, with Y equal to 45% of the average predicted per capita expenses.

Criteria For Risk Equalization

The application of risk equalization in practice is hindered because ideally the following criteria should be fulfilled:

- Appropriateness of incentives: Insurers should have incentives for efficiency and health-improving activities, and no incentives for selection and for distorting information to be used for calculating the equalization payments.

- Fairness: Ideally the risk-adjusted payments should only compensate for so-called acceptable costs, and depend only on so-called S-type risk factors. The payments should sufficiently compensate the insurers for their high-risk enrollees (‘distributional fairness’ and good predictive value), and should be sufficiently stable over time.

- Feasibility: the required data should be routinely obtainable for all potential enrollees without undue expenditures or time. The data should be resistant to manipulation by the insurers and government should be able to control the correctness of the data. There should be no conflict with privacy and ideally the system should be acceptable to all parties involved. Information that is routinely collected, standardized, and comparable across different insurers and measures that are easily validated have greater feasibility than measures that require separate data collection, validation, and processing.

In practice most potential risk equalization models appear not to fully fulfill these criteria, resulting in complicated trade-offs.

Potential Risk Adjusters

Risk equalization research started in the late 1980s. The calculation of risk-adjusted equalization payments requires a good prediction of each individual’s health expenses based on the individual’s characteristics, which are called risk adjusters. Because it is clear that age and gender alone are insufficient adjusters, the research efforts in the past two decades focused on developing health adjusters.

The inappropriate incentives related to prior utilization as a risk adjuster (‘rewarding high prior utilization’) may be reduced by combining it with diagnostic information. Widely known classification systems are the ambulatory care group system and the diagnostic cost group (DCG) models. Diagnosis-based models begin by identifying a subset of all diagnoses that predict subsequent year resource use. The many codes are grouped into more aggregated groups based on clinical, cost, and incentive considerations. Diagnosis-based risk adjusters tend to do well in predictive accuracy and feasibility. Although these models outperform a model based on age and gender only, there still exist subgroups that are substantially undercompensated.

Health status information can also be derived from the prior use of prescription drugs. Lamers et al. (1999) developed the so-called pharmacy cost groups (PCGs). They classified drugs into different therapeutic classes and further classified them on the basis of empirically determined similarities in future costs. Although PCGs are good predictors of future health care costs, a point of attention is that if the additional subsidy for a PCG-classified enrollee (far) exceeds the costs of the prescribed drugs that form the basis for PCGassignment, the insurer has an incentive to (stimulate the physician to) overprovide medication in order to ensure an increase in the future subsidies. To prevent perverse incentives, Lamers et al. (1999) used only 10% of all prescriptions to define the PCGs.

Disability and functional health status have been shown to be relatively good predictors of future expenditures, even after controlling for demographic factors and prior utilization. These indicators reflect someone’s ability to perform various activities of daily living and the degree of infirmity, and seem to be an almost ideal adjuster.

There are different opinions about the usefulness of mortality as an additional risk adjuster (see e.g., Lubitz, 1987). Van Vliet and Lamers (1998) argued that mortality should not be used as a risk adjuster because most of the excess costs associated with the high costs of dying are unpredictable. Although cause-of-death information is theoretically attractive, practical concerns include reliability, validity, availability, manipulation, auditing, privacy of the data, and perverse incentives.

The only country with a competitive health insurance market that applies mortality as a risk adjuster is Belgium. In countries with a noncompetitive health insurance market it is not unusual to use mortality as a risk adjuster.

Do We Need Perfect Risk Equalization?

It is important to emphasize that in the case of premium rate restrictions the predictable profits and losses need not be reduced to zero. One should take into account an insurer’s costs of selection and the (statistical) uncertainty about the net benefit of selection. A bad reputation resulting from selection activities such as keeping patients from the highest-quality care can be a high cost to an insurer. In addition, the information that is necessary for risk selection is not for free. So a ‘perfect’ risk equalization formula is not necessary. It should be refined to such an extent that insurers expect the costs of selection (including the cost of a bad reputation) to outweigh its benefits. By making the risk groups in the risk adjustment algorithm more homogeneous, the costs of selection increase although on average its profits fall. But it is still an unanswered question how much ‘imperfection’ is acceptable.

The European Experience With Risk Equalization: A Historical Perspective

The application of risk equalization in Europe started in the early 1990s, when several European countries started to radically reform their social health insurance system. In Belgium, Czech Republic, Germany, Israel, the Netherlands, Slovakia, and Switzerland the regulatory regime was changed such that the consumers have a guaranteed periodic choice among risk-bearing social health insurers, who are responsible for providing or purchasing health care for their enrolees. In some countries the social health insurers are called sickness funds (e.g., in Belgium, Germany, and Israel). In this article they will be indicated as ‘(health) insurers.’

Risk Adjusters And Ex-Post Cost-Based Compensations

Before 2000 all these countries used predominantly demographic risk adjusters, in combination with community-rated out-of-pocket premiums. Some countries used disability and/ or region as an additional risk adjuster(s). A disadvantage of predominantly demographic risk adjustment is that community-rated premiums create large predictable profits and losses for subgroups like the chronically sick, resulting in incentives for risk selection.

All European countries experience(d) severe implementation problems. Especially in the first years there was a serious lack of relevant data, in particular at the level of the individual enrollee. All in all the European experience indicates, in accordance with the experience in the USA that even the simplest risk equalization mechanisms are complex and that there are many start up ‘surprise problems.’

Several countries used ex-post cost-based compensations as a complement to imperfect risk equalization, for example, Belgium and the Netherlands. In Israel the insurers receive a fixed payment for each person who is diagnosed with one of the following ‘severe diseases’: end stage renal failure requiring dialysis, Gaucher’s disease, talasemia, hemophilia and acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Germany (until 2002) and Switzerland do not have any form of ex-post cost-based compensations. Consequently, the incentives for selection in Germany and Switzerland are high.

Risk Selection

It is hard to give clear evidence of selection activities in practice. Even if insurers perform risk-segmenting activities, they may argue that it is not ‘selection,’ but normal commercial behavior because they are specialized in certain segments of the market. In addition, selection activities in the form of ‘not investing in better care for unprofitable subgroups’ are difficult to detect because it is not known what would have happened if insurers had put in place appropriate incentives. Therefore, rather than hard evidence of selection, the following anecdotal evidences of selection activities reported in the European countries are cited:

- Selective advertising/using the internet;

- Accessibility problems;

- Health questionnaires;

- Delayed reimbursements;

- Offering health insurance via life insurers who make specific selections based on health inquiries;

- Selectively terminating business in unprofitable regions, for example, by closing offices in high-cost areas;

- Opening clinics in healthy regions;

- Employer-related (group) health insurer;

- Via limited provider plans such as health maintenance organizations and preferred provider organizations;

- Offering high rebates in case of a deductible;

- Information to unprofitable enrollees that they have the right to change insurer;

- Turning away applicants on the telephone and ignoring inquiries and phone calls;

- Special bonuses for agents who are successful in getting rid of the most expensive cases by shunting them off to competitors; and

- Voluntary supplementary insurance.

Acceptable Costs

Belgium is the only country in which the distinction between S-type and N-type risk factors is a relevant policy issue in practice. It was decided that medical supply should not be included in the risk equalization system. Schokkaert and Van de Voorde (2003) illustrate the nontrivial impact of this political decision on the health insurers’ results.

Although the Dutch government formally announced that the risk-equalization formula should only be based on age/ gender/health, in practice the Dutch risk equalization model also contains risk factors such as region and being self-employed. These risk factors partly reflect health status (an S-type factor) and partly other risk factors (N-type factors). A correction for the biased weights in the current risk-equalization formula would have substantial financial consequences for the Dutch insurers.

Improvements Of Risk Equalization

An effective way to prevent risk selection is to complement the demographic risk adjusters with health indicators. Then, (1) it is harder for the insurers to define who the preferred risks are; (2) on average the predictable profits/losses are less; and (3) there are less possibilities for insurers to select the preferred risks, than in the case that risk equalization is only based on age/gender. Since 2000 the risk equalization systems in several European countries have been improved by adding relevant health-based risk adjusters.

In the Netherlands the risk equalization model was extended with PCGs in 2002, with DCGs in 2004 and with an indicator of multi prior year high expenses in 2012. In Germany the incentives for risk selection were reduced by the implementation of an ex-post risk pooling for high costs insured in 2002, and by implementing a health adjuster in 2003 (yes/no being registered in an accredited disease management program). In 2009 a health-based adjuster was added that compensates for 80 severe diseases and costly and chronic diseases, based on diagnostic information and/or prescriptions. In Belgium risk adjusters based on inpatient diagnostic information and information about chronic conditions based on outpatient prescribed and reimbursed drugs were added in 2008. In Switzerland prior hospitalization has been included as a risk adjuster in 2012.

However, all these improvements in risk equalization are not necessarily a sufficient guarantee that selection will be reduced. Several arguments explain why selection may not be a major issue in the early stage of the implementation of a risk equalization mechanism in a competitive health insurance market, and why over time selection may increasingly become a problem. First, in the early stage many players, for example, consumers, health insurers, managers and providers of care, may be unfamiliar with the rules of the game. However, over time they will be better informed and can be expected to react to incentives for risk selection. Second, in the early stage the differences among health insurers with respect to benefits package, premiums, and contracted providers are relatively small. Over time they may increase. Third, most risk equalization systems have been implemented in the mandatory social health insurance system. Traditionally these health insurers are driven by social motives rather than by financial incentives. However, over time new insurers and increasing competition can make the market more incentive driven. As soon as one insurer starts with profitable selection, the others are forced to copy this strategy. Finally, one may argue that selection is not so much of a problem because doctors may be reluctant to discriminate among risks because of medical ethics. However, present ethics may change over time if the entire delivery system becomes more competitive.

How Good Are The Risk-Equalization Formulas In Practice?

Currently the most sophisticated risk-equalization formulas can be found in the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, and the USA-Medicare. How good are these formulas?

The results of an evaluation of the Dutch equalization formula 2007 indicates that this formula provides insufficient compensation for groups defined on health status, prior utilization, and prior expenses. These groups can be easily identified by the insurers. In case of an average premium, the average predictable losses per adult in these subgroups are in the order of hundreds to thousands of Euros per person per year. For example, given an average community-rated premium the average predictable loss per adult for 21% of the population who report their health status as fair/poor, equals €541. The results also indicate predictable losses for groups of insured whose disease is included as a risk-adjuster in the equalization formula, for example, heart problems and cancer. Clearly not all of these patients fulfill the criteria to be classified as a patient eligible for a high equalization payment. It may be expected that other sophisticated risk equalization algorithms, such as the ones used in Belgium, Germany, and the USA-Medicare, yield similar results.

Lessons From The European Experience

In totality the European experience indicates, in accordance with the experience in the USA, that even the simplest risk equalization mechanisms are complex and that there are many start up ‘surprise problems.’

In all countries the criterion ‘appropriate incentives’ did not appear to be a dominant one in choosing among different risk equalization models. On the contrary, redistributive effects among the insurers, feasibility (including acceptability) and fears for complexity were quite dominant criteria. In addition, one should not preclude, especially in the early days of risk equalization, an insufficient understanding of the problem. For example, the decision by the Swiss parliament in 1994 to limit the duration of the risk equalization model to a period of 13 years only can be easily countered. In autumn 2004 the Swiss parliament prolonged the formula for another 5 years, but voted once more against all propositions to improve the risk equalization formula. This decision reflects the compromise between the 49% arguing for further improvement and the 51% defending a deregulated liberal social health insurance.

Another country where risk equalization is a highly political issue is Ireland. Over a period of more than a decade there have been significant obstacles to the introduction of risk equalization because of political, legal, and implementation issues.

Another lesson is that even sophisticated risk equalization formulas currently in practice are not yet sufficiently refined and do not eliminate all incentives for risk selection that are caused by the community rating requirement.

Future Perspective Of Risk Equalization In Europe

Given that current risk equalization schemes in most countries are far from perfect, the first priority should be further investment in improvement. Investment is needed both in better data and in research and development of better risk adjusters. In addition policymakers should seriously consider the use of ex-post cost-based compensation and reconsider the use of community rating. Policymakers must understand that risk selection is not inherent to the competitive insurance market, but is primarily the result of one possible form of regulation (i.e., community rating), and that alternative forms of regulation result in other outcomes.

Improving Risk Equalization

Current risk-equalization models in Europe can be improved by adding new health adjusters such as indicators of mental illness, indicators of disability and functional restrictions, multiyear DCGs rather than one-year DCGs, multiyear prior expenses and multiyear prior hospitalization and the enrollee’s choice of a voluntary high deductible. In addition insurers might ex-post receive an ex-ante determined fixed amount for certain high-cost events (e.g., pregnancy) or diseases. New research efforts should in particular focus on individuals who are in the top 1% or top 4% of health care expenditure over a series of years because current risk equalization formulas perform worst for these groups.

The more risk equalization is improved, the more chronically ill people are likely to become preferred clients for efficient insurers, because the potential efficiency gains per person are higher for the chronically ill than for healthy persons. However, it is still questionable whether in practice a sufficiently refined risk equalization system is feasible. For example, approximately 6% of the Dutch population suffers from one or more of the 5000–8000 rare diseases for which the current formula does not compensate insurers and for which it is hard to find suitable risk adjusters. Because of the small number of people with each of these rare diseases the coefficients of the risk adjusters may change substantially from one year to the next, which conflicts with an essential precondition for ideal risk adjusters.

Improving Ex-Post Cost-Based Compensation

Ex-post cost-based compensation can be an effective complement to imperfect risk equalization, but also involve a selection-efficiency trade-off because they lower incentives for insurers to operate efficiently. However, the severity of the trade-off can be lowered by replacing existing compensation schemes with other forms of risk-sharing. Countries that currently have a uniform system in which insurers are retrospectively compensated for expenses above a threshold incurred by any enrollee (e.g., Germany), would be better off with a differentiated system in which a retrospective compensation is only given for individuals belonging to a small group of high risks determined in advance, for example, based on expenditures and hospitalization in the previous years. In this way it would be possible to increase insurers’ financial risk without significantly increasing their incentives for risk selection.

A Better Understanding Of The Regulatory Regime

Regulation of a competitive social health insurance market is a complex issue. Because many policymakers do not have sufficient understanding of the problem and the potential solutions society is often confronted with suboptimal regulatory regimes. An example is community rating. Most (if not all) policymakers confuse community rating as a goal and as a tool. Because their policy goal is that everybody in the community should pay more or less the same premium, they use mandatory community rating as a tool to achieve this goal. However, community rating creates incentives for risk selection, which may result in the adverse effects outlined in Box 1. Therefore, although community rating has some important advantages (short-term affordability, transparency, and low transaction costs of organizing cross subsidies), it also has serious negative effects in the long term, particularly as a result of insurers’ disincentives to provide good quality care to the chronically ill. Nevertheless, all European countries with a competitive social health insurance market require premiums to be community rated (although this most likely is in violation with the European regulation).

The major rationale for a competitive social health insurance market is to encourage insurers to be prudent purchasers of health care on behalf of their enrolees. Policymakers must understand that a condition sine qua non for achieving this aim is that insurers are adequately compensated for each enrolee – that is, they must receive a risk-based revenue related to each enrolee’s predicted health care expenses, either from the enrolee in the form of a risk-rated premium or from a risk equalization scheme. Insurers will then focus on efficiency rather than on risk selection, and chronically ill people will become the most preferred clients for efficient insurers, rather than undesired predictable losses. This will in turn stimulate insurers to contract with providers who have the best reputation for high-quality well-coordinated care for chronically ill people.

An alternative for community rating is to allow risk-adjusted out-of-pocket premiums within a bandwidth, for example, a factor of two or four, in combination with subsidies for certain groups to improve affordability. Insurers are then free to charge risk-adjusted premiums provided their maximum premium does not exceed the minimum premium per product, for example, by a factor of two or four. With good risk equalization, the overwhelming majority of the premiums will be within the bandwidth. Policymakers might give this strategy a serious thought. Any information surplus the insurers might have would then be focused on premium differences rather than on selection. If the insurers are required to identify any risk factors they use for differentiation of their premiums, government could try to include the S-type risk factors in the equalization formula in subsequent years. (By definition government does not want to subsidize the N-type risk factors.) In this way the reduction of solidarity that results from the insurers’ freedom to differentiate their premiums, may well be a short-term sacrifice to a long-term solution.

A Wider Application Of Risk Equalization In Europe

So far most of the risk equalization literature in Europe focused on the social health insurance markets where consumers have a periodic choice of insurer. However, risk-adjusted payments can also be applied to noncompeting purchasers of care, for example, as risk-adjusted budgets for regions within a NHS such as in England, Italy, or Spain.

The recently proposed reforms in England to abolish the primary care trusts, to allocate approximately 75% of the NHS-budget to new general practitioner (GP)-consortia and to give the consumers a free choice of GP make the formula on which resources are allocated in the English NHS even more complicated. The formula must then be calculated at the individual consumer level, rather than at the small-area level. If one individual moves from one GP-consortium to another, this person’s budget must follow the consumer. Therefore, the proposed health reforms provide England with a new challenge: how to prevent risk selection by the new GP-consortia? A first version of a person-based resource allocation formula for the NHS has already been developed.

England has a long tradition of research on resource allocation formulas. Therefore, the rich input of this English knowledge about resource allocation formulas, substantially enhances the risk equalization knowledge in Europe. A first issue is the concept of ‘health.’ In the risk equalization literature traditionally some crude proxies for health are used, such as DCGs, PCGs and other information derived from prior utilization, without much discussion about the validity of these indicators. In England, decades ago the discussion had already started about the concepts morbidity, need and demand, and about the difference between health status and need, or the various concepts of need, such as normative, felt, expressed, and comparative. Second, England has a long tradition of applying the supply of health care facilities as a so-called N-type risk factor in the allocation formula. This English experience may give interesting insights to countries as the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Germany, where supply of health care facilities is (still) considered an S-type risk factor. Third, researchers in England considered supply to be a function of health care needs and utilization, and applied econometric techniques to deal with this endogeneity problem. These insights will enrich the traditional risk equalization literature, where this endogeneity has been overlooked.

Provider Payment

Risk adjustment algorithms can also be used in the purchaser–provider relation. The rationale is that purchasers may give a risk-adjusted capitation payment to (a group of) providers of care to deliver a defined set of services to their enrollees and may try to share some of their financial risk with the providers of care. A simple form of capitation is the payment to GPs for the services they deliver themselves. If consumers have a choice among capitated providers, which mostly is the case, risk selection is an issue. It becomes more complicated if the providers’ capitation payment also includes an ex-ante determined budget for several forms of follow-up care, as in the case of GP-fundholders. These follow-up costs may range from care prescribed by the GP, for example, prescription drugs, laboratory, and physiotherapy, to all follow-up costs (the so-called total-fundholder). In the latter case, in fact the GP functions as an insurer.

The functioning and effects of risk-adjusted capitations may strongly depend on the number of persons per capitated entity: for example, 2000 (a GP) or 2 000 000 (an insurer). In case of a small number of persons the conditions of the law of the large numbers are not sufficiently fulfilled, and the capitated provider may be confronted with a substantial financial risk because of large deviations from the statistically expected result. Forms of financial risk-sharing between the purchaser and the capitated provider of care can then be applied. Risk-adjusted capitation payments and forms of financial risk-sharing (‘bonuses’) are essential elements of so-called pay-for-performance programmes. In these programmes it is crucial that the physicians’ payments are sufficiently adjusted for the case-mix composition of their practices.

It is a great challenge to apply risk adjustment on the level of the physician and to analyze the consequences of the crucial differences and similarities between capitation payments for insurers and for primary care physicians.

Conclusion

Some conceptual issues for understanding the complexity of risk equalization have been discussed and an overview of risk-adjusted equalization payments in Europe has been provided. Most of the experience in Europe is with risk-adjusted payments to insurers in competitive health insurance markets. However, the relevance of risk adjustment for provider payment is increasing.

In practice, the risk equalization algorithms in all countries are imperfect and substantially undercompensate the high-risk enrollees. In addition, all European countries also implemented premium rate restrictions in the form of community rating. Consequently, the health insurers are confronted with incentives for risk selection, which may threaten affordability, efficiency, quality of care, and consumer satisfaction. There is evidence that risk selection is a serious issue in European countries. Some countries reduced the insurers’ incentives for selection by giving them ex-post cost-based compensations. But these compensations also reduce their incentives for efficiency, resulting in a selection-efficiency trade-off. An alternative option that European countries may consider is to allow insurers to differentiate their premiums within a bandwidth, in combination with subsidies for certain groups to improve affordability.

The conclusion is that good risk equalization is an essential precondition for reaping the benefits of a competitive health insurance market. If insurers are confronted with substantial financial incentives to be irresponsive to the preferences of the chronically ill, the disadvantages of consumer choice of health insurer may outweigh its advantages. However, (also) the European experience indicates that in practice the implementation of even the simplest risk equalization scheme is very complex. This holds even more for the implementation of health-based risk equalization.

References:

- Lamers, L. M., van Vliet R. C. J. A. and van de Ven W. P. M. M. ( 1999). Pharmacy costs groups: A risk adjuster for capitation payments based on the use of prescribed drugs? Report (in Dutch) of the Institute of Health Policy and Management. Rotterdam: Erasmus University.

- Lubitz, J. (1987). Health status adjustments for Medicare capitation. Inquiry 24, 362–375.

- Schokkaert, E. and Van de Voorde, C. (2003). Belgium: Risk adjustment and financial responsibility in a centralised system. Health Policy 65, 5–19.

- Van Vliet, R. C. J. A. and Lamers, L. M. (1998). The high costs of death: Should health plans get higher payments when members die? Medical Care 36(10), 1451–1460.

- Ash, A., Porell, F., Gruenberg, L., Sawitz, E. and Beiser, A. (1989). Adjusting medicare capitation payments using prior hospitalization data. Health Care Financing Review 10(4), 17–29.

- Bevan, G. (2009). The search for a proportionate care law by formula funding in the English NHS. Financial Accountability and Management 25(1), 391–410.

- Ellis, R. P., Pope, G. C., Iezzoni, L. I., et al. (1996). Diagnosis-based risk adjustment for Medicare capitation payments. Health Care Financing Review 12(3), 101–128.

- Lamers, L. M. and van Vliet, R. C. J. A. (1996). Multiyear diagnostic information from prior hospitalizations as a risk-adjuster for capitation payments. Medical Care 34(6), 549–561.

- Newhouse, J. P. (1996). Reimbursing health plans and health providers: Efficiency in production versus selection. Journal of Economic Literature 34(3), 1236–1263.

- PBRA Team (2009). Developing a person-based resource allocation formula for allocations to general practices in England. London: The Nuffield Trust.

- Pope, G. C., Kautter, J., Ellis, R. P., et al. (2004). Risk adjustment of Medicare capitation payments using the CMS–HCC model. Health Care Financing Review 25, 119–141.

- Rice, N. and Smith, P. (2001). Capitation and risk adjustment in health care financing: An international progress report. Milbank Quarterly 79(1), 81–113.

- Stam, P. J. A., van Vliet, R. C. J. A. and van de Ven, W. P. M. M. (2010). A limited-sample benchmark approach to assess and improve the performance of risk equalization models. Journal of Health Economics 29, 426–437.

- Van Barneveld, E. M., Lamers, L. M., van Vliet, R. C. J. A. and van de Ven, W. P. M. M. (2000). Ignoring small predictable profits and losses: A new approach for measuring incentives for cream skimming. Health Care Management Science 3, 131–140.

- Van Barneveld, E. M., Lamers, L. M., van Vliet, R. C. J. A. and van de Ven, W. P. M. M. (2001). Risk sharing as a supplement to imperfect capitation: A trade-off between selection and efficiency. Journal of Health Economics 20(2), 147–168.

- Van de Ven, W. P. M. M., Beck, K., van de Voorde, C., Wasem, J. and Zmora, I. (2007). Risk adjustment and risk selection in Europe: Six years later. Health Policy 83, 162–179.

- Van de Ven, W. P. M. M. and Ellis, R. P. (2000). Risk adjustment in competitive health insurance markets. In Culyer, A. J. and Newhouse, J. P. (eds.) Handbook of health economics, ch 14, pp. 755–845. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Van de Ven, W. P. M. M., van Vliet, R. C. J. A., Schut, F. T. and van Barneveld, E. M. (2000). Access to coverage for high-risk consumers in a competitive individual health insurance market: Via premium rate restrictions or risk-adjusted premium subsidies? Journal of Health Economics 19, 311–339.

- Van Kleef, R., Beck, K., van de Ven, W. P. M. M. and van Vliet, R. C. J. A. (2008). Risk equalization and voluntary deductibles a complex interaction. Journal of Health Economics 27, 427–443.

- Weiner, J. P., Dobson, A., Maxwell, S., et al. (1996). Risk adjusted Medicare Capitation Rates Using Ambulatory and Inpatient Diagnoses. Health Care Financing Review 17, 77–100.