The existence of duplicate private health insurance (DPHI), which is observed in many countries with a National Health Service (NHS), is paradoxical at first sight. NHSs are usually characterized by universal coverage of every resident, large and comprehensive benefit packages, very low copayments or free care at the point of delivery, progressive tax financing, and are strongly guided by principles of equity in access to health care. Additionally, residents cannot opt out of the NHS, meaning that they are not given the option of not contributing to the NHSs’ financing and relying exclusively on other forms of health care. Why then would people be willing to pay for private health insurance (PHI) covering roughly the same services as the NHS? This is even more surprising because NHSs have been generally performing quite well over the last decades. This paradox is a major issue in health economics, which health economists have been trying to understand theoretically and to document through empirical work. This article presents these findings.

Before going further, it is important to define the concept of DPHI, often called also double coverage or substitutive PHI. Under DPHI, private insurers offer coverage for health care already available under public delivery systems. Note that DPHI differs from supplementary PHI (SPHI). Under SPHI, patients access additional health services not covered by the public scheme such as luxury care, elective care, long-term care, dental care, pharmaceuticals, rehabilitation, alternative or complementary medicine, or superior hotel and amenity hospital services. Also worthy of remark is that DPHI is distinct from complementary PHI, which complements the coverage of publicly insured services by covering all or part of the residual costs not otherwise reimbursed (e.g., copayments). It is worth noting that there is no full consensus as regards this terminology, as some authors use the concepts of SPHI and DPHI indifferently. DPHI should also be distinguished from ‘parallel private health insurance’ where individuals are covered by one among several parallel insurance systems. These roughly insure for the same health care but an individual is entitled to only one of the insurance systems’ benefits. For example, in the US, an individual in need of health care as a consequence of a workplace accident is covered by the Workers’ Compensation Board and not by Medicare.

Finally, note that an NHS is a necessary but not sufficient condition to observe the emergence of DPHI. According to a large review of health systems in Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, DPHI exists to different extents in the following countries with an NHS (percentages in parentheses indicate the percentage of people enjoying double coverage): Australia (43.5%), Ireland (51.2%), Italy (15.6%), New Zealand (32.8%), Portugal (17.9%), Spain (10.3%), and the UK (11.1%) (Paris et al., 2010). At the same time, double coverage is absent in other NHS-type health systems like Denmark, Norway, and Sweden.

In Section ‘Stylized Facts and Preliminary Insights,’ some stylized facts that allow a preliminary overview about health systems’ performance in the presence of double coverage are presented. Then, the main theoretical concepts that are indispensable to analyze this question are presented in Section ‘Theoretical Concerns: Uncertainty and Information.’ In the Section ‘Empirical Evidence of Uncertainty and Informational Problems: Who Buys Duplicate Private Health Insurance?’, the main results from empirical analyses that have tested several aspects of double coverage, in particular, who is more likely to purchase duplicate private insurance and why is displayed. Finally, Section ‘Political and Financial Sustainability of a DHPI Health Sector’ focuses on the political and financial sustainability of a system with duplicate private insurance.

Stylized Facts And Preliminary Insights

DPHI coverage is usually advocated for at least three reasons:

- It promotes population health.

- It limits public and global health expenditures.

- It increases population choice and health system ‘responsiveness,’ a term defined below in this section.

Roughly speaking, DPHI emerges because the NHS alone will fail to reach these aims. However, is there really a failure of NHS that justifies the emergence of DPHI? In this section, the preliminary evidence as regards these three objectives, for three NHSs, namely Portugal, Spain, and the UK, is provided. These countries are suitable cases for investigation because their public system has long lived without a significant DPHI – actually, the weight of DPHI on total health expenditures only became relatively significant (44%) after 2000.

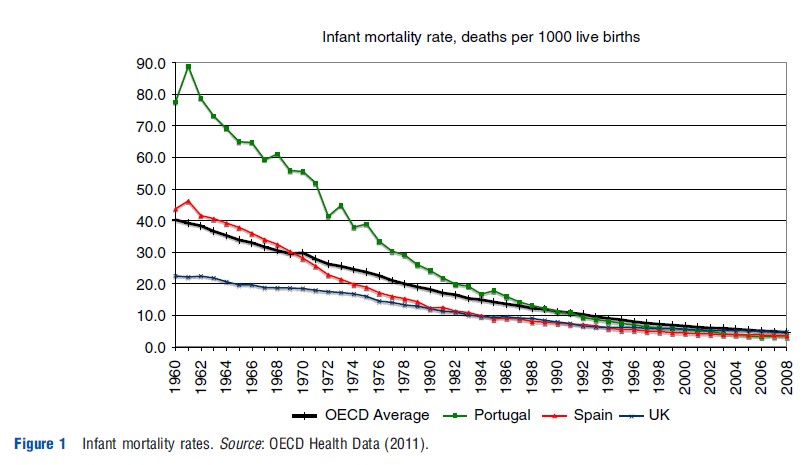

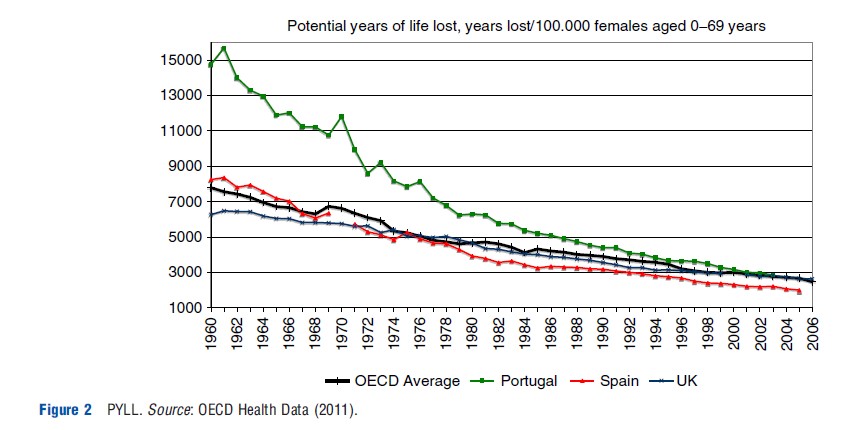

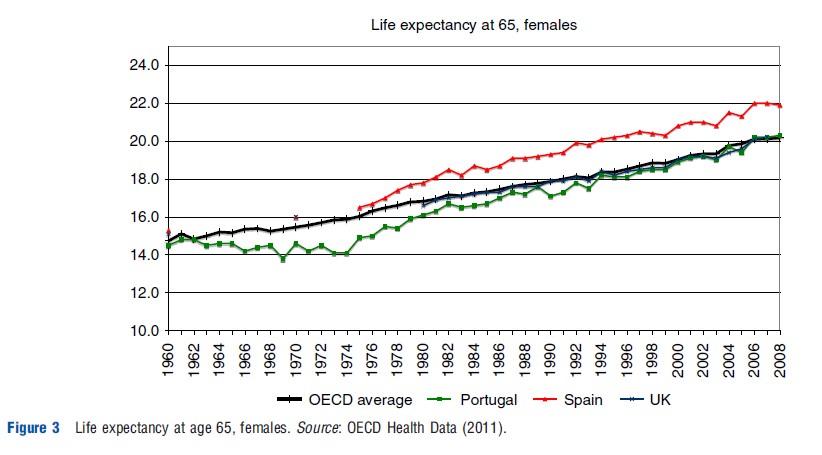

It is of course very difficult to attribute good health outcomes to a health system, because population health depends on many factors. Nevertheless, at first sight, these three public schemes certainly do not do worse than the OECD average. The three indicators commonly used to assess health systems’ performance are considered here: infant mortality, potential years of life lost (PYLL), and life expectancy at 65. In the 1960s, before the creation of the Portuguese and Spanish national services, Portugal had almost double that of Spanish infant deaths (43/ 1000) and four times those of the UK (22/1000) (Figure 1). Yet, since the late 1980s, Spain has reached UK levels, well below the OECD average, and Portugal has fallen below the OECD average since 1990. For the last 35 years both the UK and Spain have been constantly below the OECD female average as regards PYLL, whereas Portugal, starting from very high levels, has been approaching the OECD average (Figure 2). Finally, as regards life expectancy at 65 years, Spanish women live longer than any other, whereas UK women have a similar life expectancy as the OECD average. Portugal, however, has approached the OECD average in the last 20 years having started from significantly lower levels (Figure 3). It seems thus that health concerns might not be the major explanation for the development of DPHI.

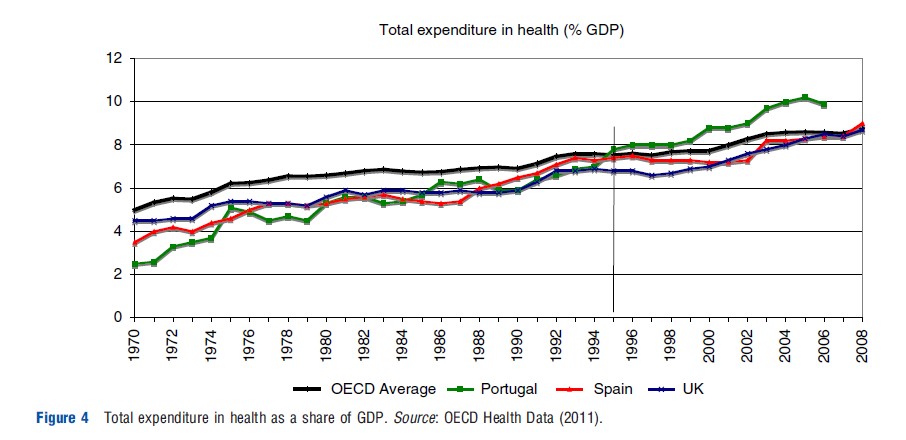

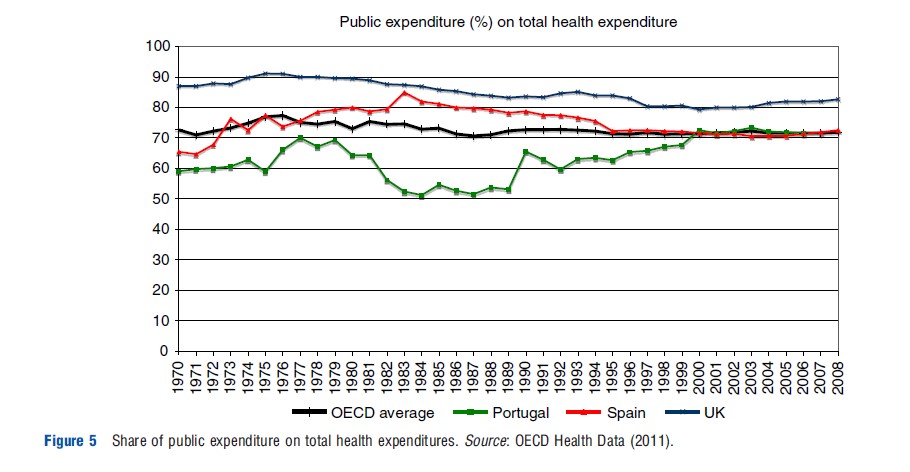

Double coverage is commonly defended as a means to restrain total and public health expenditure. Consistently, Portugal, Spain, and the UK have for long been allocating a lower-than-the-average share of their gross domestic product (GDP) to the health sector. However, the pace of growth in these countries has been quite similar to that observed elsewhere. Values have even got further above the OECD average since the mid-1990s in Portugal and in very recent years in Spain and the UK, coinciding with the development of DPHI(Figure 4). Note also that the share of public expenditures is similar in those countries as compared to the average, and has not decreased with the development of DPHI (Figure 5). Instead, since early 2000 this indicator has been constant for Spain and Portugal and has even increased for the UK. Only a deeper analysis would allow one to draw more definitive conclusions. However, at first sight, public health expenditures were not particularly high before DPHI nor has DPHI been very effective in restraining public and general health care expenditures.

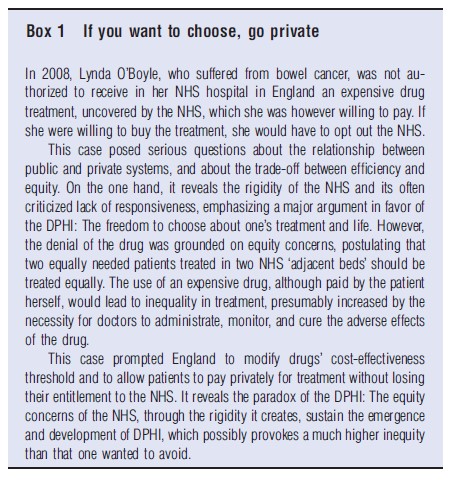

Finally, another argument relates to the supposed public service’s inability to respond to specific aspects of demand, the so-called lack of responsiveness. The NHS is usually strongly guided by the principle of horizontal equity (‘equal treatment for equal needs’); hence it provides comprehensive but needs- based uniform health care, which limits the possibility for patients to express their preference, even if they are ready to pay for them (this rigidity may sometimes create unexpected and morally conflicting situations, see Box 1 ‘If you want to choose, go private’). Additionally, principles of rationality and efficiency have prompted these three countries to adopt measures such as gatekeeping, and access to GP and hospital mainly according to the area of residence, which further limit patients’ choice. Finally, waiting lists are used to restrain health care use considerably, as a means to ration demand in the absence of significant copayments. In 2010, Portugal had 161 621 patients waiting a median time of 3.3 months for elective surgery (there were however, 248 404 waiting a median of 8.6 months in 2005); in Spain 374 000 patients were waiting an average 1.9 months in 2009; and the UK has decreased 900 000 patients waiting more than a median of 20 weeks in the 1980s to 620 000 patients waiting a median of less than 5 weeks in 2010. There are thus elements related to the rigidities of NHS-type systems that may favor double coverage. Note that recent decreases in waiting times have been in part obtained through contracts with private practices, so that the potential benefits of DPHI may play some role in these results.

Theoretical Concerns: Uncertainty And Information

To understand why DPHI coverage emerges, who buys it, and with which consequences, it is crucial to understand some economic concepts related to insurance in general and health insurance in particular. To start with, it is important to realize that the health care sector is affected by uncertainty in mainly two dimensions. First, there is unpredictability with respect to an individual health status and future health care needs. Second, there is uncertainty regarding the precise effects of a given health care procedure on a particular patient.

Regarding health status, some individuals are at a higher risk of developing diseases than others. Such a risk is the result of a combination of an individual’s genetics, aging, behavior, and environmental context. Neither the individual, nor the physicians, nor the insurers know with exactitude the status of the patient’s health. What is more, they may not even share exactly the same information but instead have ‘asymmetric information’ regarding the individual’s health status. Indeed, prior to any screening test or medical intervention, it is common to assume that the individual is more informed about his chances of developing a disease or condition than anyone else. After all, the individual is more aware of one’s family’s health condition, one’s own lifestyle, and one’s environment than one’s doctor or insurer may be. When facing the doctor, the individual may have all the incentives to disclose information – beyond everything, one wants to be treated – this is most often not the case when facing the insurer – ultimately one wants to be paid for all medical care expenses and would prefer to deny any responsibility of the events. The insurance companies’ reaction to this asymmetric information depends very much on the structure of the insurance market but generally issues like ‘adverse’ and ‘propitious selection,’ ‘moral hazard,’ and ‘insurance denial’ emerge. Below, the Sections Adverse Selection, Risk Selection, Propitious Selection and Moral Hazard discuss the extent of these effects in a duplicate health insurance market.

However, the effects of a particular health care procedure on a patient are not certain. Additionally, physicians are better able to assess the effects of medical care than the patient or insurance companies, and it may not always be of their interest to reveal such information. For example, they may increase the number of consultations aiming at greater profits. Consequently, physician’s ‘induced demand’ may arise. Section ‘Supplier-Induced Demand and Dual practice’ deals with induced demand in the context of duplicate insurance market.

Adverse Selection

Suppose some individuals in the economy have a high probability of disease and others a low one, known by the individual but unknown to the insurer. Adverse selection (also referred to as ‘‘screening’’ by some authors) may be a mean for insurance companies to force individuals to reveal their risk type. Indeed suppose they offer two types of contracts: One fully insuring individuals at a price reflecting high-risk individuals’ probability of becoming sick; another offering incomplete insurance coverage at a price reflecting low-risk individuals’ risk. The first contract is too expensive for low-risk individuals and therefore only the high-risk ones would be willing to buy it. The second would offer limited coverage at a price reflecting low-risk individuals’ probability. It would therefore not be attractive to high-risk individuals who have a lot to lose for not being completely insured. Still, low-risk individuals would be willing to buy it. Thus, by limiting the coverage of one such contract the insurance company is able to force individuals to self-select by buying the contract intended for their type and hence distinguish low- from high-risk individuals. In the end, the ‘bad’ type, i.e., the high-risk individuals end up being fully insured whereas the ‘good’ type, i.e., the low- risk individual, is prevented from being fully insured.

Note that insurance companies cannot break even by offering an insurance contract to all individuals at an average price that captures the average risk. Actually, low-risk individuals would find such a contract too expensive and therefore only high-risk individuals would end up buying it. Consequently, such a contract would not be financially viable.

The problem of adverse selection is that low-risk individuals are not fully insured by insurance companies even if they would be willing to pay for insurance. In the NHS, adverse selection is not an issue because uniform health care is provided to all resident population, irrespectively of their risk. Also, the effects of adverse selection in the insurance market are lessened when insurance takes the form of group policies. In this case a uniform coverage is offered to all individuals belonging to the group. This is the case of 50% of the duplicate insurance in Portugal, 20% in Spain, and 15% in the UK. Therefore, other things being equal, it would be expected adverse selection as being stronger in the UK and Spain than in Portugal.

It could be argued that adverse selection is not such an important issue in the context of a duplicate insurance market, as opposed to a complementary or supplementary one. In the context of a complementary/supplementary insurance market, insurance covers services not covered in the public system. Therefore, someone without insurance in this market is not insured for those services not covered by the NHS. In contrast, in a duplicate health insurance market, not being insured in the private market would not be so costly because individuals are ensured care in the NHS. Still, as stressed in the Section ‘Stylized Facts and Preliminary Insights,’ one of the reasons why individuals buy DPHI is because they are deterred by the NHS waiting lists to prompt health care. An NHS with waiting lists is thus offering incomplete health care provision just as a less than-full coverage insurance contract is. Consequently, all individuals face incomplete health care provision at the NHS and, additionally, low-risk ones face incomplete insurance coverage at the private market due to adverse selection. Therefore, also under DPHI there are individuals never fully insured even if they are willing to pay for duplicate insurance.

Empirical evidence of adverse selection is tricky because its effects may be confounded with others (see the Section Empirical Evidence of Uncertainty and Informational Problems: Who Buys Duplicate Private Health Insurance?). Still, if adverse selection alone would be present in the private market, it would be expected to find empirical evidence that some individuals (high-risk ones) are fully insured at expensive prices and others (low-risk ones) only partially insured at lower prices. To assess adverse selection’s unfavorable effects and its relative importance, it is important to identify which health care services are most affected by waiting lists or not provided at all publicly, and to understand which individuals suffer more from adverse selection.

Risk Selection

Another situation that should not be wrongly identified with adverse selection is when insurers select insurees or deny insurance on the basis of individual observable characteristics correlated to risk. For example, PHI is usually denied to individuals 65 years and older because being older is on average associated with higher medical expenses. Still, some of these individuals may be at higher risk of disease than others, which is then not observable. Hence even if insurance would not been denied, adverse selection would arise among the older.

In a duplicate insurance system individuals who are denied insurance coverage are nevertheless entitled to health care at the NHS. They may have to face long waiting times but in principle prompt care is guaranteed for emergencies and urgent situations. Yet, if they wish to buy duplicate insurance they are not able to do it. The situation is however better than in the case in which individuals have to pay the full price of health care if not insured, as it happens when the insurance market is complementary to public provision or in the absence of universal coverage.

Two arguments are commonly used to explain why risk selection exists and who might be denied insurance. First, according to theory, insurers either provide contracts based on true risks or provide different contracts to separate low- and high-risk. However, these are costly procedures which the insurers may not be willing to assume. Second, the empirical literature shows that the variance of health care costs increases with the mean, so that expenditures for high-risk groups are less predictable. Hence, insurers may prefer to provide contracts based on broad categories (age and sex) and then reject high-risk groups directly or indirectly.

In most cases selection is clearly stated in insurance contracts, for example, through an age criterion or through exclusion of benefits from preexisting conditions. Another more subtle form of selection derives from most contracts being short-term (usually 1 year), which enables insurers to modify conditions (or even avoiding renewal, even if this is usually forbidden) once a serious disease has been diagnosed. Contrasting the characteristics of the population receiving health care at the NHS with those relying on DPHI as well can also provide an indication of what constitutes a source of insurance denial. If insurance denial is a fact then there must be empirical evidence that NHS users share some characteristics that DPHI users do not. Still, results should be read with caution because asymmetries may be also due to differences in preference regarding insurance or other issues.

Propitious Selection

‘Propitious selection’ in the insurance market occurs when low- risk individuals buy more insurance than high-risk ones. One possible explanation relates to risk aversion, that is, people with a higher risk concern would tend to be more cautious, hence more likely to purchase insurance. As they are more cautious, they also adopt more preventive behavior and are less prone to health hazards. Note that this is not a problem per se: It is just a consequence driven from the fact that individuals who have a stronger preference for being insured buy more insurance.

Propitious selection may also arise because high-risk individuals underestimate their risk, prompting them to purchase less insurance. A higher willingness to pay among wealthier persons could also explain propitious selection if wealth and health risk are negatively correlated, as it is usually observed.

The empirical testing of propitious selection is not trivial. On the one hand, we would expect to find evidence that those buying DPHI or higher coverage contracts are less prone to health accidents, and hence use less curative health care. On the other hand, if propitious selection is driven by preventive behavior, those who buy health insurance would use relatively more diagnostic tests and preventive health care. Hence empirical analysis requires reliable information on individuals’ health conditions, behavioral, and environmental risks, which are generally difficult to obtain.

Moral Hazard

Moral hazard occurs when an individual facing risk changes one’s behavior depending on whether or not one is insured. For example, dental care insurance may lead individuals to be less cautious about their mouth hygiene, which may be reflected in a higher probability of caries (ex ante moral hazard). Or, in a case a tooth is removed individuals may decide toward a dental implant only in case they are insured (ex post moral hazard).

To induce individuals to exert some effort in the limitation of damages (ex ante moral hazard) or to restrain medical care use (ex post moral hazard), insurance contracts typically impose the individual part of the incurred cost by making use of deductibles and/or coinsurance rates. This means that the consequence of moral hazard is partial insurance (incomplete coverage), just as in the case of adverse selection.

Because moral hazard consists of a reaction to insurance, it is present under an NHS just as in the private market, for the same level of insurance coverage. Still, the two sectors deal with moral hazard in very different ways. The NHS deals with it by rationing health care, for example, through waiting lists, gatekeeping, and limiting individuals’ choices. Actually delayed access to health care is a sort of limited insurance coverage and can thus give incentives to prevention and consequent limitation of damages (ex ante moral hazard) or restrain individual use of medical care (ex post moral hazard). Similarly, in the private market, individuals are typically not fully insured (due to deductibles and coinsurance rates) and the same mechanism applies. The extent to which each sector is affected by moral hazard depends therefore on the importance of incomplete coverage of each sector.

Curiously, a duplicate insurance system may deal well with moral hazard. Indeed, if on the one hand individuals are twice insured, on the other hand, NHS health care and private insurance are mutually exclusive. In other words, as one owns an insurance policy for a given health event, if a patient goes to the NHS, the insurance coverage is not claimed and vice versa. In principle, the patient faces two sectors with incomplete coverage that deal better or worse with moral hazard. In contrast, complementary insurance destroys any incentives to promote prevention or deter unneeded care that may exist in the public sector because the individual is usually fully insured (because privately the individual is insured for the out-of-pocket payment).

To conclude concerning the presence of moral hazard: it is essential to test whether insurance contracts offering more coverage are associated with greater use of health care. Note that even though very different in their causes adverse selection and moral hazard lead exactly to the same observed market effect: Insurance contracts with less coverage are associated to individuals using less health care. As is discussed in the Section Empirical Evidence of Uncertainty and Informational Problems: Who Buys Duplicate Private Health Insurance?, it is not always easy to distinguish the two effects.

Supplier-Induced Demand And Dual Practice

We now turn to the implications of uncertainty regarding the effect of health care on patients. The physician is obviously the most informed and can use this information for his own benefit by increasing health care acts beyond what is adequate and necessary. Obviously physician behavior depends very much on the incentives faced. As a point of fact, supplierinduced demand (SID) is to be expected in the private market where physicians are usually paid by fee for service. Yet, insurance companies have been trying to redesign physicians’ incentives to restrain such practice.

SID should be common to any health care system relying partially or fully in the private market. In this respect, there is no reason to think that a duplicate insurance system is more prone to SID than other systems are. After all, the determinant is the size of the private market and the incentives imposed by insurance companies. Still, in a duplicate insurance system an additional effect comes into action because physicians are often allowed dual practice, i.e., they provide health care both at the NHS and at the private market. There is general awareness that physicians deviate patients toward their private practice where they benefit from additional rents for the health care provided and can induce demand for private benefit. Additionally, SID can easily be transformed in a common and cultural practice because the same physicians act publicly and privately.

Finally, it is important to note that also in an NHS, SID may exist. In an NHS, physicians are usually paid on the basis of a fixed salary, but they may induce health care consumption due to the practice of defensive medicine with a view to avoiding malpractice liability.

It is a challenge to identify empirical evidence of SID. A strategy of identification would be to contrast health care provided across physicians for the same health condition, except that SID can be the norm. For example, in some countries, patients are given another appointment once the results of diagnostic tests are known whereas in others, results and accordingly prescription are given by postal mail or telephone (except for abnormal cases). Also, physicians may be members of a specific culture of medical practice that pushes them toward excess health care. Nonetheless, a duplicate health insurance system allows for the contrast between private and NHS medical practice where differences would be (partially) explained by SID.

Empirical Evidence Of Uncertainty And Informational Problems: Who Buys Duplicate Private Health Insurance?

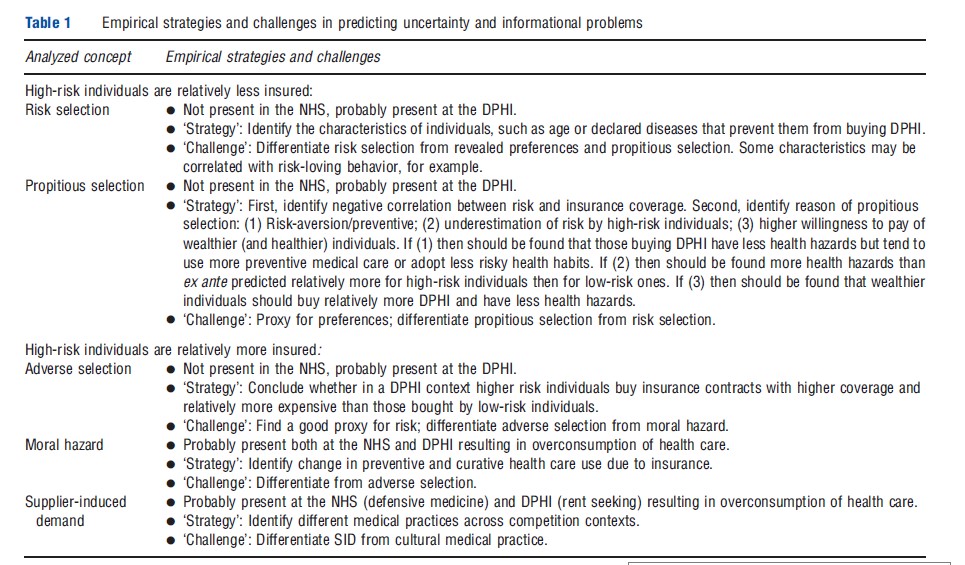

Testing for empirical evidence of uncertainty and informational problems in insurance markets is not easy because several forces can be confounded. Yet, it is important to precisely identify which problems are present because each raises different equity and efficiency concerns and leads to different policy recommendations.

Table 1 summarizes the empirical prediction of each of the effects discussed in the Section Theoretical Concerns: Uncertainty and Information and helps in following the upcoming discussion. One should start to understand whether insurance coverage depends on the type of risk and then follow by inferring which mechanism is at the foundation of such outcome. If it is observed that high-risk individuals buy less DPHI than low-risk individuals it can be due to either risk selection or propitious selection. The empirical challenge consists precisely in identifying which of the two effects is in place because although risk selection and some causes of propitious selection may call for government intervention, that is less the case if propitious selection is due to more risk-averse individuals tending to buy more insurance – after all, individuals just act according to their own preference.

If however, it is observed that high-risk individuals are relatively more insured, adverse selection may be at play and instead, it is low-risk individuals who are denied insurance. Still the measure of risk may be inconclusive. Indeed, in practice, it may just be observed that higher coverage insurance contracts are associated with more health care expenditures. This can be due to not only adverse selection but also due to moral hazard. In other terms, people with private insurance have higher expenditures either because high-risk individuals are more likely to purchase high-coverage contracts (adverse selection) or because people with higher coverage have lower incentives to parsimonious health care use (moral hazard).

A somewhat orthogonal problem to the risk issue is to what extent health care use is induced beyond what is adequate because physicians target higher profits. If this is the case there is SID. Incentives to induce demand may be related, for example, to generous fee for service reimbursement schemes under DPHI, or to very low copayments that ease the inducement process. Hence evidence on moral hazard may indeed be overestimated if the inducement of demand effect is not controlled for. The empirical strategy consists in identifying different medical practices across competition contexts but it is obviously a challenge to distinguish SID from cultural medical practice. Additionally, different medical practices may as well be explained by distinctive regional administrations or governances.

Although disentangling empirically the informational problems is challenging, some research has led to interesting results in the DPHI context. Confirming the seminal results of the Rand experiment, some UK studies have consistently confirmed a decrease in drug consumption which follows an increase in the copayment supporting the evidence of ex post moral hazard. Olivella and Vera-Herna´ ndez (2013) use data of the British Household Panel Survey for the period 1996–2007 to test empirical evidence of asymmetric information and distinguish the different effects at play. They contrast health care use of individuals having bought PHI with that of those who obtained PHI from their employer as a fringe benefit, using three measures of health care use: (1) hospitalization in a fully privately funded hospital, (2) hospitalization in publicly funded hospital, and (3) GP visits. Their reasoning is as follows. People with individual PHI are those who explicitly decided to buy it, and are called ‘deciders’; the other group includes people who obtained PHI form their employer, i.e., they did not decide to buy it and are called the ‘nondeciders.’ Both deciders’ and nondeciders’ insurance contracts are equally affected by moral hazard and thus differences across the two groups cannot be due to moral hazard. Instead, if deciders use more health care services than the nondeciders, then adverse selection prevails (deciders use more care because they are in worse health, hence high risks are more likely to buy PHI). In contrast, if deciders use less health care services, propitious selection or risk selection prevails (deciders use less care because they enjoy a better health, hence low risks are more likely to buy PHI). The authors find that individuals having decided to buy a PHI use more health care irrespectively of the measure used, concluding on the existence of adverse selection.

In contrast with this latter finding, Doiron et al. (2008) suggest evidence of propitious selection in DPHI, using Australian data. They find that healthier individuals purchase relatively more DPHI. In this case, the difficulty is then to distinguish this effect from risk selection by private insurers, which would lead to a similar result. To do so, they observe that people engaging in risk-taking behaviors (smoking, drinking, and lack of exercise) demand less private insurance coverage. Thus the authors put forward that relatively more risk-averse individuals are more likely to buy DPHI. Additionally, the assumption that insurers deny insurance to high-risk individuals seems partly discarded by the higher insurance coverage among people with long-term conditions. These two studies, in different contexts, thus show opposite results. If an earlier literature is considerd, findings are more sustaining that DPHI is associated to a healthier condition, although these studies do not try to explain the correlation.

The empirical evidence of SID has long been and remains a subject of controversy among health economists. Recent natural experiments however show that substantial variations in copayments produce effects that are similar to those observed in the Rand experiment, whose design made the occurrence of SID very unlikely. Hence observed ex post moral hazard is certainly a more plausible explanation than SID for higher health care use under DPHI.

Other empirical issues related to DPHI deserve also to be mentioned, even if less related to the theoretical problems presented in the Section Theoretical Concerns: Uncertainty and Information. To begin with, the decision to buy DPHI cannot be analyzed without considering what happens in the NHS. The demand for private insurance depends on the perceived quality in both public and private sectors. One of the most popular indicators of NHS quality is waiting lists and waiting times, which are easy to obtain and to which people are usually highly sensitive. There is evidence that long waiting lists, expected waiting times, or more generally the perceived quality gap between the NHS and private provision are determinants for people to insure privately. These findings confirm empirically that responsiveness is a relevant factor for the emergence of DPHI.

Finally, most studies confirm the strong relationship between private insurance and high socioeconomic status, in particular, income and education. Supplemental or DPHI is without doubt a normal good, which is more purchased by richer people. Income is hence obviously one of the main determinants of the demand for PHI. This last finding poses crucial questions from a welfare viewpoint because then DPHI may contribute to inequity in health. If DPHI only allows for luxurious services unrelated to quality of clinical procedures (better amenities, faster care, etc.), this may not be such a relevant problem. However, if double coverage allows access to better care that unsatisfactory NHS cannot offer, this is a serious social concern. The higher use of physician services under double coverage would sustain the latter assumption. This conclusion would be reinforced if private insurers, through higher financial capacities, are able to attract better doctors under a dual practice regime. Unfortunately, to our best knowledge, no study has assessed the impact of DPHI on quality of care (probably because quality is quite difficult to measure). The higher health care use under DPHI also questions the efficiency of duplication in a context of scarce resources.

Political And Financial Sustainability Of A DHPI Health Sector

So far, we have examined individual decisions with regard to purchasing private insurance and consumption of health care services in a context of double coverage. In this section, the potential impact of double coverage is discussed at an aggregate level, at the health system, or country level. What could explain the consensus in favor of double coverage? Does the existence of DPHI threaten the political sustainability of the NHS? What is the impact of double coverage on health care expenditures? Does it impose a higher financial burden on the NHS, or does it alleviate this burden?

First, political sustainability is considered. Suppose, as confirmed in the empirical literature, that richer people are more likely to purchase private insurance. These people will thus be paying higher taxes (assuming nonregressive taxation, as it is usually the case) without enjoying one of its major benefits, namely public health care provision through the NHS. Hence they may vote against the existence of an NHS, or at least against paying high taxes to finance it. As low-income people may also want to avoid large contributions and thus prefer lower level of health care provision, in the end the support for high public provision will decrease. However, three factors are likely to modify this finding of public under-provision:

- Opinion polls show the existence of a health-specific altruism and concern for equity in health, hence even richer people may support public provision of health care to the poor.

- Poor people are in most countries exempt from taxes and copayments, so that they favor a higher level of publicly- provided care.

- There is no perfect correlation between wealth and health, hence rich people experiencing poor health may also favor public care because its price will be lower than that of private insurance, even in a context of progressive taxation.

To conclude, the majority will vote for a lower level of public provision but would not choose zero public care. In a nutshell, this theory justifies the preference for a system with double coverage, although with a lower public provision than the one in the absence of a private sector. To our best knowledge, political questions around double coverage have never received empirical validation. The only evidence so far is that people tend to favor increased public spending after it has decreased and the reverse after it has increased (Tuohy et al., 2004). This result may emphasize the consensus for a target level of public expenditures compensated by private ones.

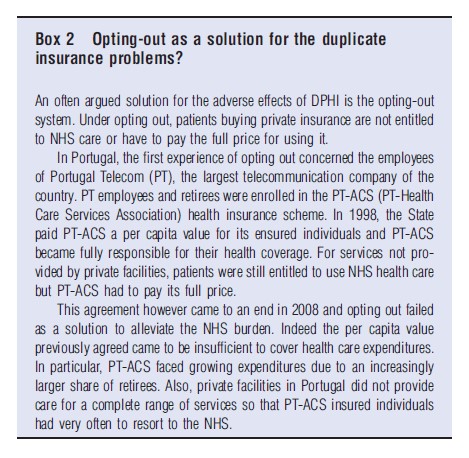

As regards financial consequences and economic sustainability, it is often put forward that DPHI may alleviate the burden on the public sector through providing care to a share of the population. This was one of the major motivations for the governments that favored the emergence of DPHI. However, the impact on total health expenditures depends on many factors. First, it depends on whether private providers are able to offer care at a lower cost than the one they would have experienced in the public sector, which is not that clear. Additionally, private insurers generally reimburse physicians through fee for service whereas salary payments have traditionally characterized NHS-type systems. Therefore physicians are more likely to tend to induce demand in the private sector. Second, double coverage is usually accompanied by dual practice, that is, physicians combining public and private practice, whose effects on health care expenditures are difficult to assess. However, dual practice enables doctors to earn additional revenue in the private sector allowing public institutions to pay lower wages, whereas attracting good doctors. Physicians in the public sector may also provide better care to build a reputation for their private activity, but perhaps also overtreat or induce demand. Physicians may also divert resources and patients from the public sector to their private practices. They may also ‘import’ more resource-consuming practice style of the private sector to their public activity. Finally, it is to be noted that evidence suggests a higher health care use for people with double coverage, in Portugal, Spain, Italy, Ireland, and the UK. In this regard, see Box 2 – Optingout as a solution for the duplicate insurance problems?

In a nutshell, public–private interactions pass through a series of complex mechanisms whose final consequences are difficult to assess. A correlation between public and private health care expenditures is generally observed, but it can hardly be concluded that the former is driven by the latter given that both are influenced by the same determinants. What is granted is that health care expenditures in countries with double coverage have increased at a path that is common to most OECD countries, and its efficiency in achieving good population health is comparable too. Some studies report however that an increase in the private share of total health care expenditures is associated with a subsequent decline in public health spending as a proportion of total public expenditure. This would tend to sustain the hypothesis of the private sector alleviating the burden of the public sector in detriment of other theoretical assumptions. Yet studies consistently show that double coverage is associated with a higher use of health care services.

References:

- Doiron, D., Jones, G. and Savage, E. (2008). Healthy, wealthy and insured? The role of self-assessed health in the demand for private health insurance. Health Economics 17(3), 317–334.

- Olivella, P. and Vera-Herna´ndez, M. (2013). Testing for asymmetric information in private health insurance. The Economic Journal 123, 96–130.

- Paris, V., Devaux, M. and Wei, L. (2010). Health systems institutional characteristics: A survey of 29 countries. OECD Health Working Papers no. 50, OECD publishing.

- Tuohy, C. H., Flood, C. M. and Stabile, M. (2004). How does private finance affect public health care systems? Marshaling the evidence from OECD nations. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 29(3), 359–396.

- Barros, P. P. and de Almeida Simoes, J. (2007). Portugal: Health system review. Health Systems in Transition 9(5), 1–140.

- Boyle, S. (2011). United Kingdom (England): Health system review. Health Systems in Transition 13(1), 1–486.

- Garc´ıa-Armesto, S., Abad´ıa-Taira, M. B., Du´ran, A., Herna´ndez-Quevedo, C. and Bernal-Delgado, E. (2010). Spain: Health system review. Health Systems in Transition 12(4), 1–295.

- OECD (2010). OECD Health Data 2010 – Version: October 2010. Available at: http://www.oecd.org/document/30/0,3746,en_2649_37407_12968734_1_1_1_37407,00.html (accessed 21.07.11).

- Barros, P. P., Machado, M. and Sanz de Galdeano, A. (2008). Moral hazard and the demand for health services: A matching estimator approach. Journal of Health Economics 27(4), 1006–1025.

- Besley, T., Hall, J. and Preston, I. (1999). The demand for private health insurance: Do waiting lists matter? Journal of Public Economics 72(2), 155–181.

- Chiappori, P. -A. and Salanie´, B. (2000). Testing for asymmetric information in insurance markets. Journal of Political Economy 108, 56–78.

- Cullis, J. G., Jones, P. R. and Propper, C. (2000). Waiting lists and medical treatment. Handbook of health economics. Ch. 23. The Netherlands: Elsevier.

- Jones, A. M., Koolman, X. and Van Doorslaer, E. (2006). The impact of having supplementary private health insurance on the uses of specialists. Annals of Economics and Statistics 83/84, 251–275.