Dual practice among doctors, which the literature often refers to as dual (or multiple) job-holding among health workers, is a phenomenon that can be observed in most countries with both public and private health care systems.

The term ‘multiple job-holding’ is defined as working simultaneously in more than one paid job. Any worker can hold several jobs at one time, and health professionals are no exception. Multiple job-holding in the health sector can take various forms. Doctors may combine medical practice with other related activities, such as research or teaching, for example, or with a totally unrelated activity, as in many developing countries. They may also hold more than one job within the public (or private) sector, or in both sectors simultaneously. This article focuses on the last option, that is, dual practice among doctors whose main job is in the public sector but who also do clinical work in the private sector.

Despite the prevalence of multiple job-holding among health workers, the phenomenon is largely undocumented. It is nevertheless allowed in most countries with mixed health systems, with two main exceptions, Canada and China, where it is forbidden by law. As a result, dual practice among doctors is widespread in European countries, prominent examples being Ireland, where 90% of the doctors employed in state hospitals also work in the private sector; and the UK, where 60% of state-employed doctors do so. Data also exist for countries outside Europe, for example, Australia and New Zealand, wherein according to the Royal Australasian College of Physicians, 79% and 43% of public sector doctors, respectively, hold some jobs in the private sector. In less developed countries, the exclusively state-employed doctor is a fading figure, due to low public-sector salaries. Dual practice is therefore widespread in Asian countries (Thailand, Vietnam, India, among others), Africa (Egypt, Zambia, Mozambique, etc.), Latin America (in Peru, almost 100% of doctors are dual practitioners), and also in Eastern Europe, wherein despite a rapidly growing private health market, doctors are reluctant to give up their public sector jobs entirely.

Just like many others, doctors may have various reasons for holding more than one job. Possibly, the most powerful being economic motivation. The intuition is that, what with overtime restrictions in the main job, people will be willing to earn extra income by taking on a second job, if it is sufficiently well paid. A recent empirical study for Norway by Godager and Luras, provides the evidence that, after a decrease in income due to shortage of patients, general practitioners have reacted by increasing the hours devoted to community health service. Other reasons leading doctors to hold more than one job include: (1) complementarities between jobs, either in terms of income (public sector stability combined with private sector earnings that are higher on average, albeit more variable) or nonmonetary advantages (opportunities to expand professional contacts or obtain recognition and prestige within the profession), and also technological and training complementarities (a second job can enable doctors to widen their experience and/ or learn new techniques); (2) professional and institutional factors relating to workload and work satisfaction, or ineffective organization, structural deficiencies, and unsatisfactory working conditions in the public health sector; and (3) personal characteristics (age, gender, household structure, etc.).

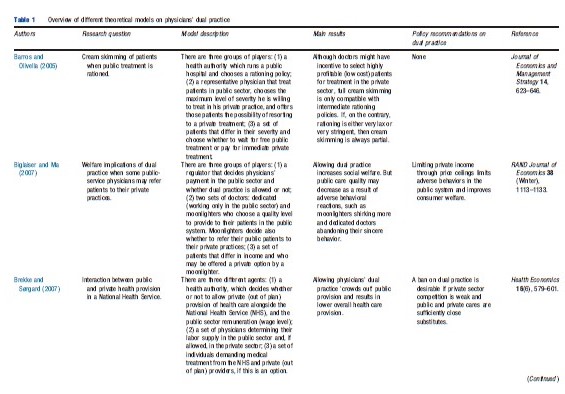

The economic theory underlying dual practice is still scant and relatively recent. Few theoretical models have been developed to analyze the issue (see Table 1 for a summary of the theoretical literature), and there is a notable lack of empirical studies on the subject.

Dual Practice: A Context For Discussion

Despite the prevalence of dual practice among doctors in the majority of mixed health systems, there is a surprising lack of evidence regarding the potential impact on the efficiency of health care resource management. Although allowing health professionals to hold more than one job may have some positive consequences, it may also give rise to a degree of opportunistic behavior that could compromise the efficiency and quality of public health provision. This is why dual practice among doctors is subject to social controversy. Detailed below are some of the arguments for and against dual practice, together with their theoretical underpinnings.

Costs Of Dual Practice

It is generally acknowledged that dual practice may have three potentially negative consequences for public health provision: (1) poorer care quality, (2) longer waiting times and waiting lists, and (3) higher costs. Although these three problems are directly interlinked (e.g., longer waiting times can lead to poor quality of care), in the remaining part of this article they are presented as independent issues, along with the related, but limited, scientific literature.

The problem of the deterioration of the quality of care in public health services due to dual practice on the part of doctors is directly linked to incentives. Dual practice doctors may have incentives to dedicate as much time and effort as possible to their private work, and therefore fail to complete their hours effectively in their public jobs either by making less effort or by taking on a lower work load. Unjustified absenteeism and shirking by health professionals are quite common in many developing countries, although there is evidence, albeit anecdotic, that these are not unknown phenomena in western economies. However, the empirical studies that report this behavior are unable to separate the effect of dual practice from that of poor organization and general lack of motivation toward effort.

Potential shirking of professional responsibilities has been widely studied in the economic literature. Inherent in these research models is the notion of asymmetric information, relating to the fact that employers cannot observe the efforts of their workers (or the result of that effort) and supervision is costly. As contracts cannot be contingent on effort, doctors may have other incentives attributing to their less than the socially desirable level of effort into diagnosing and treating patients, with negative repercussions for health care quality.

When doctors are dual providers, the reduction in their care quality may result not from lack of dedication to the public job, but from their strategic undermining of patients’ perception of public health care (a more subtle kind of physician-induced demand) so that more patients opt for private treatment. The motives for this are mainly economic, driven by the fact that the public sector pays a fixed salary, whereas in the private sector incentive schemes are more common. In a paper by Brekke and Sørgard (2007), dual practice leads doctors to skimp on their effort in the public sector in order to process fewer public sector patients and thus increase the demand for private treatment. In Biglaiser and Ma (2007), it is shown that only a fraction of doctors, who are classified as ‘moonlighters’, provide minimal service quality in the public sector and have incentives to refer patients out of the public system. Although the quality of public health care could still diminish, the authors show that this need not be the case, given that health authorities can utilize the savings in public health costs resulting from the diversion of patients to the private sector to improve the quality of service from ‘dedicated’ doctors working exclusively in the public health sector. Finally, Delfgaauw (2007) suggests that average public health care quality (interpreted in their model as the probability of receiving high quality care from an altruistic doctor) suffers because of dual practice, thus penalizing the poor who cannot afford private treatment.

A large part of the literature focuses on the design of contracts incorporating incentives to encourage desirable behavior. It is generally agreed that, for doctors working exclusively in one sector, to strike the optimum balance between cost and performance, it is necessary to combine a purely prospective payment system with partial cost reimbursement (i.e., adopting a mixed payment system). If doctors are dual providers, the effectiveness of incentives to discourage opportunistic behavior on the part of doctors does not depend entirely on the type of payment system used in the public sector. It also depends on how they would be paid in a potential second job. It has been suggested that a mixed payment system is also the best alternative for dual practitioners, although the cost reimbursement rule is likely to be more complicated. Depending on whether the relationship between public and private practice is one of substitution or complementarity, the optimal rule will yield a higher or lower return on costs than when doctors do not hold two jobs at the same time (Rickman and McGuire, 1999).

Another issue being closely linked to the deterioration of the quality of public health care is the fact that health care delivery by dual practitioners is sometimes associated with longer waiting times and longer waiting lists in the public sector. The origin of this problem may also be twofold. Firstly, it may be the result of incentives for doctors to shirk in the public sector and save their efforts for the private sector. Secondly, dual practitioners may have strategic incentives for enabling public sector waiting times and waiting lists grow. Along these lines, Iversen (1997) shows that if admissions to public sector waiting lists are rationed, the waiting time for patients will increase when their doctors are allowed to work in the private sector in their free time. Doctors will be motivated by the desire to increase their private earnings, in this case by maintaining long waiting lists in the public sector so that more patients are willing to pay for private treatment.

Table 1 Overview of different theoretical models on physicians’ dual practice

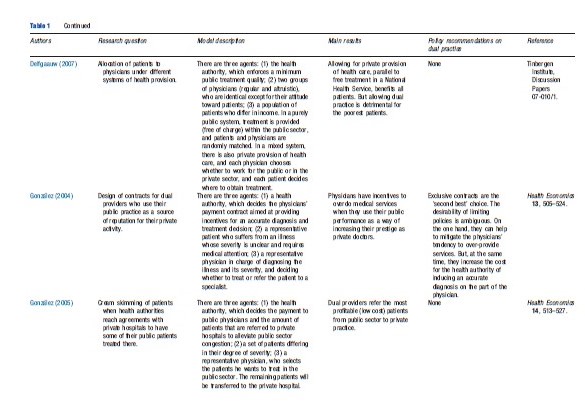

Table 1.1 Continued

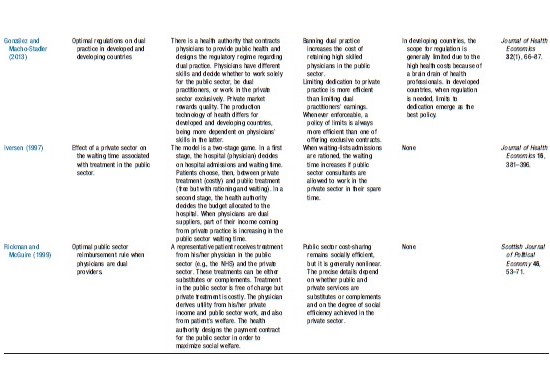

Table 1.2

Finally, dual practice by doctors can increase public sector direct costs in various ways. These include opportunistic behavior, such as the appropriation of material paid by the public sector or the use of public sector equipment to treat private patients. Although this kind of behavior is more frequent in developing countries, there is anecdotic evidence to show that it also takes place in western economies.

The cost of public health care may also increase if doctors have incentives to practice ‘cream skimming.’ This means selecting patients for treatment on the basis of either seriousness of their condition or their likelihood of recovery. In an environment of asymmetric information, cream skimming can often be the result of a prospective payment system, which encourages overtreatment of patients with minor ailments and under-treatment of serious cases. In a context with dual practitioners, cream-skimming may be explained as the result of doctors having incentives to refer less serious cases to their private practices, and leave more serious cases to the public sector. Barros and Olivella (2005) and Gonza´lez (2005) studied this phenomenon in a context of public sector waiting lists. The second of these studies shows that doctors holding more than one job have (purely economic) incentives to divert less serious (thus, less costly) cases to the private sector when the health authority decides to use private hospitals to alleviate congestion in the public sector, a policy that has recently been applied in many EU countries. Barros and Olivella (2005) stress that, when public treatment is rationed, the actual scope for cream skimming depends on the waiting list admission criteria used by the health authority. In fact, the scope for cream skimming is limited both by laxity, which results in a waiting list with a higher proportion of mild cases who will be less willing to pay for private treatment, and by extreme strictness, which reduces waiting times. Therefore, according to these authors, only an ‘intermediate’ policy will allow dual providers to divert less serious patients to their private practices, thus affecting public health costs.

Finally, it could be argued that dual practice is sometimes accompanied not by shirking but by precisely the opposite kind of behavior. Doctors may try to build their professional reputation and prestige through their work in the public sector and thus increase their private sector earnings. In this case, public health care would not suffer, but treatment costs might increase through doctors prescribing stronger (and more expensive) treatments (Gonzalez, 2004).

Benefits Of Dual Practice

Allowing doctors to work in the public and private sectors at the same time also carries some benefits for public health care provision.

In many countries, by allowing dual practice, governments are able to retain their best health professionals at less cost. If a high percentage of doctors abandon the public sector, care quality will be badly affected. This is potentially a serious problem in developing countries, where low salaries imply there is often a shortage of doctors in the public sector. An article by Gonzalez and Macho-Stadler (2013) illustrates this possibility using a theoretical model where doctors differ in their levels of skill, which is understood as their capacity to deliver adequate health care. A ban on dual practice reduces the number of doctors working in the public sector. The impact this causes on the total amount of public health provision is particularly significant if the private market rewards quality and thus draws the more skilled doctors away from the public sector.

Also, allowing doctors to work in the private sector to supplement their public sector salaries can have the positive effect of reducing the prevalence of informal payments, which are so widespread in developing and transitional economies. Informal payments constitute an informal market for health care within the confines of public health care networks, and, compromises governmental efforts to improve efficiency and equity in the delivery of health services. It was to reduce this problem that Greece legalized dual practice by doctors in 2003.

When there are complementarities between the tasks performed in different jobs, working in different working environments can enrich the professional experience of dual practitioners. Sometimes, working in the private sector allows doctors to access new technologies and improve their knowledge and technical expertise. This benefits both their private and public sector patients. The latter could benefit not only directly, if the new techniques or technology are introduced in public hospitals, but also indirectly, through improvements in professional skill and experience.

Finally, the incentives of dual providers to direct their public sector patients into the private sector can be potentially beneficial in aggregate welfare terms. This is the case if the diversion involves higher income patients who are able to afford private treatment. Thus, the more altruistic kind of doctor may advise poor patients to seek free treatment in a public hospital, and refer only those who can afford it to their private practice. This is precisely the conclusion reached in the paper by Biglaiser and Ma (2007) mentioned earlier, in which allowing dual practice is found to result in welfare gains. The motivation is twofold. Firstly, there is a saving in public sector costs, where the numbers of patients being treated will decrease as some are diverted to the private sector. Secondly, efficiency will improve because patients in the private sector will receive medical treatment of quality for which they are willing to pay. This type of argument must be treated with some caution, however, because only if there are real differences in quality between public and private health provisions, will there be patients willing to pay for private treatment. This could mean that the rich and the poor would receive unequal medical treatment, that is, a clear two-tier system. There is also some empirical evidence to show that people from low income, poorly educated groups are often the most likely to respond to inducement, to use private services and pay for private treatment instead of using the subsidized public health service.

An Overview Of Dual Practice Interventions

Whether physicians’ dual practice should be regulated in some way, and how health authorities should best intervene are two difficult questions for which the literature has not yet found unanimous answers. As mentioned already, previous theoretical studies are rather ambiguous when it comes to identifying the ultimate impact of dual practice on the efficiency and quality of public health care provision. More importantly, there has been no solid empirical research to enable us to quantify the costs and benefits of allowing (or banning) dual practice.

The reality is that dual practice by doctors is regulated in a fair number of countries, although regulations differ enormously from one country to another. Canada and China are two examples of the very few countries where dual practice is prohibited. There is disagreement in the literature as to the effectiveness of prohibition. Brekke and Sørgard (2007) find that the banning of dual practice is an efficient policy in cases where the private health sector is not highly competitive, or patients perceive public and private health care as substitutes. In both these situations, the crowding-out effect of physicians’ dual practice on public health care is so strong that dual practice is welfare-reducing and banning is desirable. Gonzalez and Macho-Stadler (2013) nevertheless stress that a ban on dual practice does not appear to be a good strategy. In developed countries, professional ethics and self-regulation are well established and can reduce the incidence of unacceptable behavior. At the same time, dual practice enables governments to retain highly qualified professionals at a relatively low cost. In these countries, therefore, the gains from banning dual practice would not offset the costs. In less developed countries, although the institutional environment is weak and the work environment permissive, prohibition still appears undesirable. These countries often suffer from a heavy ‘brain-drain’ of doctors from the public sector in search of better job opportunities. If the prohibition of dual practice means that even fewer doctors are attracted to the public sector, the poorest patients, who cannot afford private treatment, will find quality health care frankly difficult to access. Finally, prohibition is not found to be a good strategy in Biglaiser and Ma (2007) because it cancels out the efficiency gains being generated by dual practitioners diverting those patients who are willing to the private sector where they can obtain better quality treatment in return for payment.

If prohibition is not the best solution, what other options are available? Governments worldwide have tackled this issue in a wide variety of ways. Some countries, such as Italy, Portugal, or Spain, among others, have taken the alternative of offering doctors some kind of premium (a salary bonus or promotion points) in exchange for voluntarily restricting their professional activity to the public sector. The limited theoretical literature on the subject suggests that this kind of policy is optimal only in certain circumstances: (1) when it is not possible to design incentive contracts to encourage desirable behavior for health professionals (Gonzalez, 2005) and (2) when other regulations – particularly, dual practice restrictions – are difficult to implement (Gonzalez and Macho-Stadler, 2013).

In developing countries, exclusive contracts are a still less desirable option. Leaving aside the financial constraints affecting these countries, exclusive contracts will inevitably attract more poorly skilled doctors with less chance of making money in the private sector. Poor countries sometimes lack sufficient clinical technology and clearly defined treatment protocols, and doctors often work in isolation. As a result, the quality of treatment in the public sector largely depends on the skill of the doctor. Thus, the efficiency gains from this policy will tend to be minimal (Gonzalez and Macho-Stadler, 2013).

Another measure adopted by some countries is to place restrictions on dual practice. For instance, the UK has placed an upper limit on the amount of money dual practitioners are allowed to earn in the private sector. Biglaiser and Ma (2007) examined this option and show that, when the probability of doctors’ shirking depends on their earning potential in the private sector, it is socially optimal to allow dual practice but cap doctors’ private earnings, by means of price-ceilings. This enables the health authority to compensate for the loss in public sector health care quality due to dishonest doctors’ shirking, with efficiency gains derived from dual practice, as mentioned above. Gonzalez and Macho-Stadler (2013) show that it will always be more efficient to limit doctors’ dedication to private practice rather than the earnings they make from it, because the latter will only affect highly skilled doctors, who will have to reduce their dedication to private practice to comply with earning constraints. Although this may be the case, it is also no less true that limits on dedication to private practice are much harder to implement and enforce than the ceiling on earnings.

Finally, regulations in countries such as Austria, France, Germany, Ireland, and Italy are oriented toward offering doctors incentives to enable their private practice from public hospitals, while specifying the maximum amount of private work that can be provided within public facilities. This kind of policy has the advantage of facilitating supervision, reducing opportunistic behavior, and easing the enforcement of restrictions.

Most dual practice control policies have been introduced in developed countries, wherein theoretically speaking, professional ethics and existing control mechanisms provide a guarantee against serious side effects. In the developing world, however, there is little control over dual practice, despite growing interest in the problem among public decision-makers in such areas. Gonzalez and Macho-Stadler (2013) show that despite the risk of opportunistic behavior among dual practitioners in developing countries, direct regulation of dual practice is unlikely to be desirable because it carries the risk of pushing away the best doctors and thus reducing the population’s access to quality health care. Furthermore, the implementation of any of these policies will require credible contracting institutions, which developing economies mostly lack. Therefore, in contexts such as these, regulations will only work subject to improvements in the contractual and institutional framework.

References:

- Barros, P. P. and Olivella, P. (2005). Waiting lists and patient selection. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy 14, 623–646.

- Biglaiser, G. and Ma, C-t. A. (2007). RAND Journal of Economics 38, 1113–1133.

- Brekke, K. R. and Sørgard, L. (2007). Public versus private health care in a national health service. Health Economics 16(6), 579–601.

- Delfgaauw, J. (2007). Dedicated doctors: Public and private provision of heath care with altruistic physicians. Tinbergen Institute, Discussion Papers 07-010/1.

- Gonzalez, P. (2004). ‘‘Should physicians’’ dual practice be limited? An incentive approach. Health Economics 13, 505–524.

- Gonza´lez, P. (2005). On a policy of transferring public patients to private practice. Health Economics 14, 513–527.

- Gonza´lez, P. and Macho-Stadler, I. (2013). A theoretical approach to dual practice regulations in the health sector. Journal of Health Economics 32(1), 66–87.

- Iversen, T. (1997). The effect of a private sector on the waiting time in a national health service. Journal of Health Economics 16, 381–396.

- Rickman, N. and McGuire, A. (1999). Regulating providers’ reimbursement in a mixed market for health care. Scottish Journal of Political Economy 46, 53–71.

- Eggleston, K. and Bir, A. (2006). Physician dual practice. Health Policy 78, 157–166.

- Ferrinho, P., Van Lerberghe, W., Fronteira, I., Hipo´lito, F. and Biscaia, A. (2004). Dual practice in the health care sector: Review of evidence. Human Resources for Health 2, 1–17.

- Garc´ıa-Prado, A. and Gonza´lez, P. (2007). Policy and regulatory responses to dual practice in the health sector. Health Policy 84, 142–152.

- Garc´ıa-Prado, A. and Gonza´lez, P. (2011). Whom do physicians work for? An analysis of dual practice in the health sector. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 36(2), 265–294.

- Holmstrom, B. and Milgrom, P. (1991). Multitask principal-agent analyses: Incentive contracts, asset ownership, and job design. Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization 7(Special issue), 24–52.

- Socha, K. Z. and Bech, M. (2011). Physician dual practice: A review of literature. Health Policy 102(1), 1–7.