Heterogeneity in hospital costs has often been used to convince citizens and policy makers of the extent of inefficiency in hospital care provision. Classification of hospital stays into diagnosis related groups (DRGs) has made it possible to place patients into groups that are supposed to be medically homogenous and to compare the cost of stays for similar cases in different hospitals. In a paper devoted to the political history of Medicare’s transition to prospective payments per DRG, Mayes (2006) cited the unbelievably rapid growth rates of hospital costs in the USA: approximately 15% per year during the 1970s. However, there was still doubt about the contribution of inefficiency to such growth rates. Once DRGs were defined, policy makers finally reacted to differences in costs between hospitals for the same procedures. The introduction of prospective payments per DRG was decided on for Medicare, with the goal of forcing hospitals to increase efficiency. Similarly, in France, the debate on reforming hospital payments advanced in 1997, when the Ministry of Health decided to make public the differences in costs between French hospitals. Large differences in costs that were difficult to justify pointed to large differences in efficiency across hospitals, and showed that some of them were quite inefficient.

Nowadays, there is a general trend in all developed countries toward improving efficiency in hospital care through implementation of prospective payment systems (PPSs). Following the example of Medicare in 1983, other payers in the USA adopted PPS for inpatient care. European countries first adopted a global budget system to contain hospital costs during the 1980s, before turning to PPSs per DRG.

The Basic Inspiration Of Prospective Payment Systems

The assumption at the root of a PPS is that any deviation in cost for a stay in a given DRG is because of inefficiency. Economists use the term ‘moral hazard’ to refer to the idea that the payer (the insurer or the regulator) cannot observe, much less monitor the efforts undertaken by hospital managers to minimize costs. Paying hospitals a fixed price per stay in a given DRG provides a powerful incentive for managers to minimize costs. Indeed, hospitals are supposed to keep the rent earned when their costs are lower than the fixed price. Conversely, they risk running operating losses if their costs are above DRG payment rates.

This payment scheme provides a perfect incentive for cost reduction because the payment is a lump sum per stay defined irrespective of a given hospital’s actual cost. Yet, the regulator has an informational problem: she does not know how much care costs when the hospital is fully efficient (i.e., the ‘true’ minimal cost for a stay in a given DRG). The level of the lump sum defined by the regulator can lead the hospital to bankruptcy or generate rents that are costly for tax payers (or the insured). This informational problem is solved by assuming that hospitals are homogeneous. In that case, differences in costs are caused only by moral hazard. Hence, an appropriate rule of payment is to offer each hospital a lump sum payment per stay defined on the basis of average costs observed in other hospitals for stays in the same DRG.

Shleifer’s yardstick competition model provides the theoretical foundation for a PPS. This model is based on rather unrealistic assumptions: homogeneity of hospitals, homogeneity of patients for the same pathology, and fixed quality of care. Many studies have underscored the great diversity in hospitals’ conditions of care delivery (teaching status, share of low-income patients, local wage level, etc.). Input prices can differ depending on location; care quality may vary, as may the severity of illnesses of admitted patients. These studies highlight the risks of such a PPS, namely selection of patients and a lowering of care quality. Indeed, hospitals which are subject to exogenous factors that lead to higher costs have to find ways to lower costs in order to avoid bankruptcy.

Sources Of Heterogeneity In Hospital Costs

To avoid such problems, the regulator must design payments that allow for exogenous and legitimate sources of cost heterogeneity. This idea was formalized early on by Schleifer in his paper, published in 1985, one year after the beginning of Medicare’s payment reform. He considered the case where the regulator can allow for the predicted impact on costs of observable characteristics that cannot be altered by the hospital. At first, Medicare adjusted its payments by a regional cost-of-labor index and gave extra payment to teaching hospitals. Currently, Medicare payments are adjusted for teaching hospitals, for a disproportionate share of indigent patients, and for local wage rates. In England, the national price per HRG (the English DRG) is adjusted for unavoidable differences in factor prices for staff, land, and building construction. More generally, in European countries, payment rates are adjusted for structural variables such as teaching, status, and region.

There is a theoretical debate on how observable causes of cost differences between hospitals should be allowed for in a PPS. Mougeot and Naegelen (2005) pointed out that most theoreticians implicitly assume that prospective payments are combined with a lump sum transfer. They show that this transfer should generally take the form of a tax paid by the hospital. Indeed, in a PPS hospitals whose costs are lower than the price per DRG receive a surplus, called a rent, which is costly to the tax payer. Social welfare will be maximized if this rent is extracted through a tax. But such a tax is not feasible in practice, given that most health care agencies do not have the power to ‘fine’ hospitals. If lump sum transfers are not feasible, it is possible to adjust fixed prices per DRG in order to reflect exogenous cost differences between hospitals. In this case, price adjustment should not necessarily be proportional to the extra cost; it can be optimal to discriminate against low-cost or high-cost hospitals by setting the price adjustment above or below marginal cost.

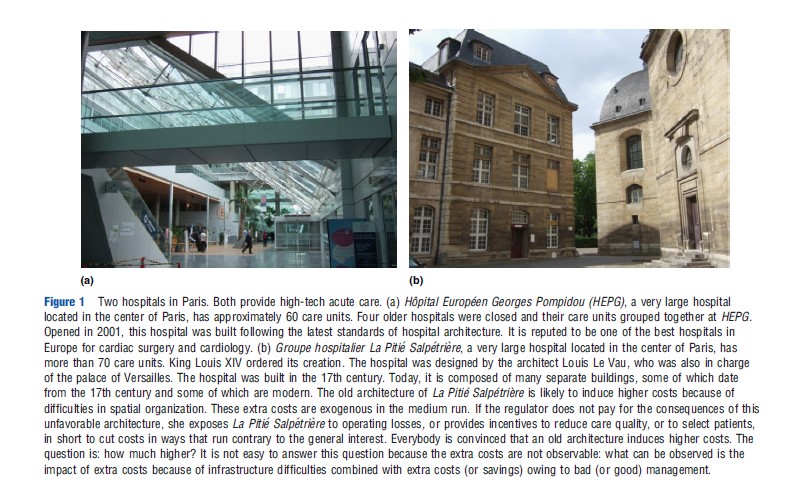

However, the main difficulty is that many sources of cost variability are not observable by the regulator, or the regulator cannot measure their impact on hospital costs. Figure 1 concerns two hospitals in Paris. The Hopital Europeen Georges Pompidou was built recently, whereas most of La Pitie´ Salpetriere is very old and bears all the weight of its long history. Even if the regulator is convinced that La Pitie´ Salpetriere has extra costs because of the age of its buildings, the magnitude of these extra costs cannot be measured. At best, the regulator can observe the impact of additional costs because of poor infrastructure combined with extra costs (or savings) due to bad (or good) management, or combined with many other sources of cost variability: care quality, scale and scope economies, other hospital characteristics.

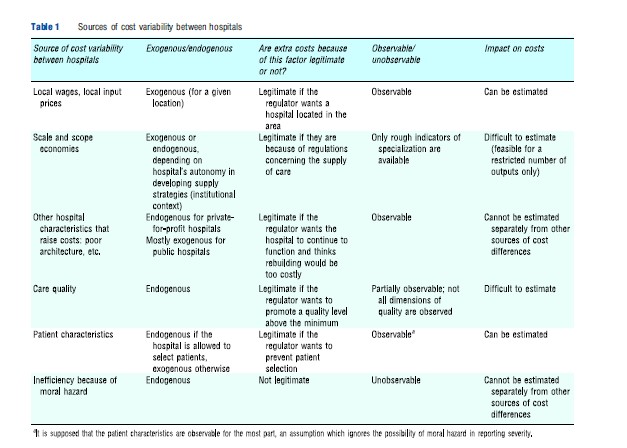

How can unobservable sources of cost heterogeneity be dealt with? How can we distinguish between differences in cost because of cost containment efforts and differences that cannot be reduced because they are a result of exogenous unobserved sources of hospital heterogeneity? Before turning to this question, the possible sources of cost heterogeneity are characterized by splitting them into six large categories (see Table 1). This classification is rather simplistic and debatable, but it may help in understanding what is at stake in the question of hospital heterogeneity.

For each source of cost variability, it is essential to know whether it is exogenous or endogenous, legitimate or illegitimate, and whether its impact on costs can be evaluated. A factor is considered to be exogenous if the hospital manager cannot influence its level. Legitimacy is based on citizens’ willingness to pay ( preferences ). Consider for instance a hospital located in an area with limited road access. This induces higher transportation costs and possibly higher wages. Are people willing to pay an extra amount for a hospital located in this area? If the extra cost is considered illegitimate, the regulator will not adjust the DRG rate and the hospital must either reorganize or close down. Similarly, indigent patients induce higher costs because their hospital stays are generally longer. If the care system is supposed to offer similar access to care to every citizen, adjusting payments to avoid selection of patients is legitimate. The exogeneity of a cost factor may depend on hospital status: in France, patient characteristics are exogenous for public and private nonprofit hospitals, which are not allowed to select patients, whereas patient characteristics can be considered endogenous for private-for-profit hospitals.

Economies of scale are obtained when a lot of activity in one type of care service results in a lower cost per stay. Economies of scope arise when an appropriate mix of care services results in a lower cost per stay. Very narrow specialization is generally linked to scale economies, combined with scope diseconomies. Scale and scope economies may be exogenous or endogenous, depending on the hospital’s autonomy in developing supply strategies. The institutional context plays an important role: in the National Health Service of England, hospitals that are run by Foundation Trusts (FTs) have more freedom to shape their supply of care than other hospitals. In France, scale and scope economies are endogenous for private-for-profit hospitals but exogenous for public hospitals. The latter have a given capacity and their mandate obliges them to offer a broad mix of services in order to meet needs. Hence, extra costs because of diseconomies of scope for a private-for-profit hospital can be deemed illegitimate, if the hospital is not constrained by a public mandate.

The fact that a source of cost heterogeneity is observable does not imply that its impact on costs can be evaluated. As in the example of La Pitie´ Salpetriere, the regulator cannot measure extra costs associated with the age of the hospital buildings separately from other sources of extra costs. The factors considered in the table are shown in blue cells when their impacts on costs are likely to be difficult to estimate: they include moral hazard, of course, as well as some hospital characteristics, but also care quality and scale or scope economies. Indeed, quality is multidimensional and rather difficult to observe. Scope economies are not easy to detect because currently available econometric tests are feasible only for a very small number of types of care services, which is not satisfactory, given the number of DRGs (at least several hundred) or Major Diagnosis Categories (several dozen).

How To Pay For Unobservable Heterogeneity?

Fixed payments per DRG put pressure on hospitals to compete. Because payments levels are set at average cost, hospitals which are affected by exogenous factors that induce higher than average costs risk losses. If they are already operating at full efficiency, they cannot realize further savings through efficiency gains. Hence, careless implementation of a PPS is likely to create undesirable incentives for selecting patients and lowering care quality. A regulator who aims at maximizing social welfare must design a payment system that creates virtuous incentives for enhancing hospital efficiency, without providing deleterious incentives for patient selection and quality reduction.

To address this question, many theoretical papers have tried to improve the basic model by lifting assumptions relative to patient and hospital homogeneity, and by allowing for endogenous levels in the number of procedures and quality of treatment. Using various theoretical frameworks and hypotheses, these papers show that social welfare can be improved through a mixed payment system that combines a fixed price with partial reimbursement of the actual cost of treatment per stay. To deal with unobserved sources of heterogeneity in costs, the regulator can construct a menu of contracts that combine a lump-sum transfer with partial reimbursement of actual costs. When the hospital chooses a contract, it reveals its unobserved cost component. Currently, however, such a payment scheme is not implemented in any health system. In fact, the theoretical design of the contracts often relies on unobservable variables or functions, such as, for instance, the function describing the disutility of the hospital manager’s cost reduction efforts. Hence, such theoretical designs are hardly used in reality.

Another strategy is to use econometrics to evaluate unobservable sources of cost heterogeneity. The sources of hospital cost heterogeneity are summarized in Table 1. A hospital’s activity is more or less costly, depending on its infrastructure, the existence of economies of scale or of scope, the quality of care and the cost reduction effort provided by the hospital manager (moral hazard). Moral hazard can be split into two components: long-term moral hazard and transitory moral hazard. Long-term moral hazard is supposed to be time invariant: the hospital management can be permanently inefficient. An example of permanent inefficiency would be an obsolete elevator which is very slow and subject to frequent breakdowns and which is not replaced for several years. Transitory moral hazard is linked to the manager’s transitory cost reduction efforts. For instance, the manager can be more or less rigorous, each year, when negotiating prices for supplies or for services provided to the hospital by outside firms. It would be optimal for social welfare to eliminate long-term moral hazard as well as transitory moral hazard. However, it is very difficult to separate long-term moral hazard from other sources of cost heterogeneity which are legitimate.

The use of a three-dimensional nested database makes it possible to identify transitory moral hazard. It is then possible to design a payment that allows for hospital heterogeneity in costs, while still providing incentives to increase efficiency because it does not reimburse costs due to transitory moral hazard (see the technical appendix).

A fully PPS reimburses each stay with a fixed price regardless of the actual cost of the stay: The payment systems currently implemented in most countries take some observable sources of cost heterogeneity, such as local input prices, into account. A preferable method of payment would be to allow for observable and some unobservable sources of cost heterogeneity, provided they are time invariant. With such a payment rule, the regulator reimburses each hospital for extra costs that might correspond to undesirable long-term moral hazard, but which can as well correspond to legitimate heterogeneity. Nevertheless, this method of payment creates incentives to increase efficiency because it does not reimburse extra costs that are a result of transitory moral hazard.

The general idea is that the regulator has no means to disentangle legitimate and illegitimate sources of timeinvariant cost heterogeneity, i.e., to separate the wheat from the chaff. In this context, it might be preferable to accept to pay for long-term moral hazard in order not to penalize hospitals which have legitimate sources of cost heterogeneity. Is this view unreasonable? The question becomes an empirical one: if transitory moral hazard has a substantial impact on cost variability, it would be possible to achieve large gains in efficiency even while paying for permanent sources of hospital cost variability.

An empirical estimation has been carried out by Dormont and Milcent (2005) on a sample of stays for acute myocardial infarction in French public hospitals. It appears that the cost variability because of transitory moral hazard was quite sizeable. Simulations show that substantial budget savings – at least 20% – could be expected from implementation of a payment rule that takes all unobservable hospital heterogeneity into account, provided that it is time invariant. This payment rule is easy to implement if the regulator has information about costs of hospital stays. A drawback is that it gives higher reimbursements to hospitals which are costlier because of permanently inefficient management. However, it has the great advantage of reimbursing high quality care. Moreover, it can lead to substantial savings, because it provides incentives to reduce costs linked to transitory moral hazard, whose influence on cost variability can be sizeable

Technical Appendix: Designing Payments That Allow For Cost Heterogeneity Between Hospitals

The use of a three-dimensional nested database, with information recorded at three levels (stays–hospitals–years), makes it possible to identify transitory moral hazard and to estimate its effect on hospital cost variability. For a given DRG, we can observe the cost Ci,h,t of the stay i, which occurred in hospital h in year t. This cost can be decomposed as follows: Ci,h,t = Ci,h,t+a+ηh+εh,t+ui,h,t . If stays for the same DRG always had the same cost, the cost would always be equal to the constant a. A fully PPS is based on this assumption, which implies that the other terms of the right-hand side of the equation would be equal to zero.

As stated above, there are some legitimate sources of cost variability, some of which are observable: patient characteristics, local input prices. The impact of these characteristics on costs can be estimated: we denote this cost heterogeneity as Ci,h,t . Given the observable characteristics, cost variabilitythen depends on the sum of three random variables: ηh+εh,t+ui,h,t . The term ui,h,t represents unobservable heterogeneity between patients: its average is equal to zero at the hospital level. Hence, for given observable hospital characteristics, hospital costs are affected by the terms ηh and εh,t. These random variables are not observed but can be estimated with a three-dimensional database.

By definition, the term ηh specifies time-constant unobservable hospital heterogeneity. It can be seen as the result of several components summarized in Table 1. In short, a hospital’s activity is more or less costly, depending on several factors: its infrastructure, the existence of economies of scale or of scope, the quality of care and the cost reduction effort provided by the hospital manager (moral hazard). As a component of a time-invariant term (ηh), the moral hazard involved here is long term: the hospital management can be permanently inefficient. It would be optimal for social welfare to eliminate long-term moral hazard as well as transitory moral hazard. However, long-term moral hazard cannot be separated from the other components of ηh , which are legitimate sources of cost heterogeneity.

The term εh,t is defined as the deviation, ceteris paribus, for a given year t, of hospital h’s cost in relation to its average cost. It can be seen as the result of transitory moral hazard, measurement errors and unobserved transitory shocks affecting hospital costs. Actually, measurement errors and unobserved transitory shocks are likely to be of slight importance. Indeed, a measurement error belonging to εh,t would be patient invariant by definition. In other words, it would be replicated for each stay in the same hospital during the same year, which is unlikely. As for transitory shocks, they should be observable if they are justifiable. It is true that any hospital can be affected by a shock in a given year: an electrical failure, for example. However, the regulator would be well advised to classify a priori these incidents as moral hazard, in order to give hospitals incentives to declare them, when the extra costs they induce are justifiable and exceptional. Hence εh,t is mostly made of moral hazard: an econometric test run on French data by Dormont and Milcent (2005) gave empirical support to this conjecture. More precisely, εh,t is an indicator of transitory moral hazard (indeed, all time-invariant components ofunobserved hospital heterogeneity are represented in the term ηh).

A fully PPS reimburses each stay with a fixed price Pi,h,t = a, whatever the actual cost of the stay Ci,h,t. The payment systems currently implemented in most countries take some observable sources of cost heterogeneity into account. With our notation, the reimbursement then equals: Pi,h,t= Ci,h,t + a. A preferable method of payment would be to allow for observable and some unobservable sources of cost heterogeneity, provided they are time invariant. The payment would be equal to: Pi,h,t = Ci,h,t + a+ηh . With such a payment rule, the regulator in effect tailors reimbursement to each hospital. Indeed, the component ηh is specific to hospital h. It might correspond to undesirable long-term moral hazard, but it can also correspond to legitimate heterogeneity. This method of payment can nevertheless create incentives to increase efficiency because it does not reimburse extra costs that are due to transitory moral hazard (εh,t is not a component of payment Pi,h,t).

References:

- Dormont, B. and Milcent, C. (2005). How to regulate heterogeneous hospitals? Journal of Economics and Management Strategy 4(3), 591–621.

- Mayes, R. (2006). The origins, development, and passage of Medicare’s revolutionary prospective payment system. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 62(1), 21–55.

- Mougeot, M. and Naegelen, F. (2005). Hospital price regulation and expenditure cap policy. Journal of Health Economics 24, 55–72.

- Chalkley, M. and Malcomson, J. M. (2000). Government purchasing of health services. In Culyer, A. J. and Newhouse, J. P. (eds.) Handbook of health economics, vol. 1A, pp 847–890. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Laffont, J. J. and Tirole, J. (1993). A theory of incentives in procurement and regulation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Ma, A. (1994). Health care payment systems: Cost and quality incentives. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy 3(1), 93–112.

- Miraldo, M., Siciliani, L. and Street, A. (2011). Price adjustment in the hospital sector. Journal of Health Economics 30, 112–125.

- Mougeot, M. and Naegelen, F. (2012). Price adjustment in the hospital sector: How should the NHS discriminate between providers? A comment on Miraldo, Siciliani and Street. Journal of Health Economics 31, 319–322.

- Shleifer, A. (1985). A theory of yardstick competition. RAND Journal of Economics 16, 319–327.