In most countries, private health care insurance is provided by managed care organizations (MCOs). They appeared in the late 1990s as an alternative to the traditional fee-for-service health insurance contract. Their main role is to administer and manage the provision of health care services to their clients within a general objective of cost containment in the health care sector. In this sense, an MCO is a middleman contracting with health care providers on the one side and with enrollees on the other. The latter obtain advantageous fees when visiting in-plan providers and the former guarantee a larger base of clients. The most common types of these organizations are preferred provider organizations (PPOs) and health maintenance organizations (HMOs).

An HMO offers health care insurance to individuals as a liaison with providers (hospitals, doctors, etc.) on a prepaid basis. HMOs require members to select a primary care physician, a doctor who acts as a gatekeeper to direct access to specialized medical services whenever the guidelines of the HMO recommend it.

A PPO offers private health insurance to its members (health benefits and medical coverage) from a network of health care providers contracted by the PPO. The main characteristics of a PPO are:

- health care providers contracted with the PPO are reimbursed on a fee-for-service basis;

- enrollees in a PPO do not require referral from a primary care physician to access specialized care;

- enrollees sign a contract defined by a fixed premium, a copayment on the health care services received, and possibly, a deductible;

- enrollees have freedom to visit out-of-plan providers (with a possible penalty in the form of the payment of a greater share of the provider’s fees);

- drug prescription may be covered as well when enrollees patronize participating pharmacies; and

- preventive care procedures (check ups, cancer screenings, prenatal care, and other services) may also be available.

To summarize, a PPO is a particular instance of integration between upstream providers and downstream third-party payers. The aim of this article is to describe how providers compete to become preferred providers.

The PPOs Market Place

Competition in the health care market takes place at different levels. MCOs (and in particular, PPOs) compete to attract enrollees and providers compete for patients and compete to be selected by PPOs. Often, this competition develops in the framework of a regulated market by some public agency aiming at achieving some social welfare goal.

Most of the literature on PPOs deals with the selection of providers, with competition among providers (hospitals and physicians), and with the effects of the design of the insurance contracts on competition. Usually, it is assumed that individuals have already chosen an insurance contract. Some of these individuals may become ill and seek health care services. Sick individuals are referred to as patients. They are the focus of attention of the demand side of the market. Generically, individuals are supposed to make their choices to maximize their level of satisfaction. Focusing the attention on the choice of a PPO, an individual compares on the one hand the premium, co-payment, and deductibles of alternative insurance contracts and on the other hand, the set of in-plan providers. Also, the individual will try to guess how transparent is the information provided by the PPO on medical costs and its negotiation capacity as these are elements characterizing an insurance contract. Also, the individual may consider the plans of the PPOs to enlarge the present set of enrolled providers. All in all, the best plan for an individual reflects the balance between (expected) health care needs, the freedom to choose providers, and his(her) budget constraint. Finally, enrollees should have proper incentives to use the in-plan providers so that the PPOs fulfill their role in the health care system.

In the supply side of the market, one of the reasons for the appearance of MCOs is the need for cost containment in the health care system. As a consequence, managed care has transformed the way hospitals compete for patients and physicians. From competing in quality and provision of services and amenities, managed care introduces the so-called ‘selective contracting’ of providers. This means that not all available providers in a community are able to contract with the managed care plan. Accordingly, hospitals and physicians compete to be selected as in-plan providers. An issue appears on the size of the PPOs. The negotiation between a provider and a PPO to become in-plan determines the discounts that in turn, are linked to expected utilization. Therefore, the PPO faces a dilemma. Limiting the number of providers in-plan favors achieving the utilization levels, and thus the capacity to offer better deals to enrollees. But a too short list of in-plan providers may discourage individuals to contract with the PPO because it limits the freedom to choose. Empirical evidence seems to point to the prevalence of the obtention of lower prices associated with this selective contracting due to the capacity of the managed care plan to control the number of providers and idle capacity. Also, the size of the managed care plan may be an additional element toward lower prices. The selective contracting mechanism has induced a process of integration between providers and insurers. In this integration, we find upstream health providers deciding first the prices charged to the insurers for a bundle of services, and next insurers deciding the premiums of the (menu of) contracts offered to individuals. The interesting finding is that net revenues, upstream or downstream, result from the combination of a competition effect and a coordination effect. The former reflects the impact of downstream competition on upstream providers; the latter captures the efficiency gains from integration. A PPO, by maintaining some separation between providers and insurers, softens premium competition with respect to the other more integrated structures like HMOs. Accordingly, PPOs emerge as more profitable than HMOs, adding an argument to the popularity of PPOs.

Surprisingly enough, there is very little literature on the process of selecting providers and on competition among providers when different reimbursement rules apply, according to the provider chosen by the patient. Generally, patients have to bear part of the cost of the treatment provided by an in-plan care provider. If an out-of-plan care provider is visited instead, the patient pays the full price and obtains the indemnity from the insurer specified in the insurance contract. It should be clear that the setting of the indemnity associated with the out-of-plan provider is a crucial element in the choice of an insurance contract. Three alternatives can be envisaged, capturing three organizations of the health care systems.

The first one simply does not provide coverage for choices outside the preferred provider set. This is called a pure preferred provider system that captures a pure public system of health provision, such as the Spanish one, where a patient visiting a private provider (instead of a public one) has to bear the full cost of the treatment (unless the patient has some duplicate private insurance). The second alternative, labeled fixed copayment rule, defines an indemnity equal to what the patient would have obtained had she(he) visited a preferred provider (that is the price of the in-plan provider is used as reference price to determine the indemnity). This alternative captures the idea of indemnity based on a reference price inspired by some features of the French system. Also, it captures some important features of the pharmaceutical sector. Finally, the third alternative, the so-called fixed reimbursement rate rule, considers the same co-payment rate on all providers. It is equivalent to the scenario where all providers have been selected by the insurer. This captures some features of the German system, where, together with the public providers, there is a fringe of private providers regulated through bilateral agreements.

There is also an alternative way to endogenously form the PPO. This is the so-called any willing provider mechanism. Under this approach a third-party payer announces a reimbursement rate and the set of health plan conditions. Any provider finding these acceptable is allowed to join the network.

When providers make simultaneous decisions on prices and qualities, this set-up approaches the primary care sector, whereas when decisions are sequential, first (high-cost, long- run decision on) qualities and then (low-cost, short-run decisions on) prices, the set-up approaches the specialized health care sector. When the market is organized around profitmaximizer providers, the fixed-co-payment rule on the primary health care sector is enough to make providers choose the optimal (welfare-maximizing) price and quality levels. In contrast, there is no way to attain such an outcome in the specialized health care sector, unless some regulation is introduced. This issue is discussed next.

Alternatively, the mixed public–private provision of health care and the regulation of the market by a public health authority can also be considered. Two scenarios are envisaged. In the first one, an agency regulates both price and quality of the public provider and acts as a Stackelberg leader whereas private providers are followers. It turns out that the first-mover advantage of the public provider coupled with a fixed copayment rule are sufficient instruments to achieve the first-best allocation. In the second scenario, regulation takes the form of a three-stage game where the regulator sets the level of quality to maximize welfare, then the private providers decide their quality levels, and finally providers compete in prices in a mixed oligopoly fashion. Now, leadership by direct operation of one provider does not ensure achievement of the social optimum, due to the strategic effects resulting from the sequential nature of the decisions. Comparison of these two ways of modeling the role of a public regulator allows to derive some normative conclusions on the implementation of price controls in the health care systems of some European Union member states. All governments have looked at ways to contain health expenditures. Direct and indirect controls over health care providers have been imposed in some countries where co-payments play an important role. In several countries, controls on prices (pharmaceuticals, per-day treatment in hospitals) exist, whereas in others, no such controls exist. Copayment changes have been frequent in the European countries, mostly limited to the value of the co-payment, whereas maintaining its structure (fixed reimbursement rates). Moreover, co-payments are designed with insurance coverage in mind (typically, they have an upper limit). No role as a market mechanism underlies the choice of the structure and the value of co-payments. Thus, the relative unsuccessful episodes of cost containment through co-payments is not totally surprising. The structure of the co-payment has been kept constant, although the results reported highlight the fact that changing its structure would have a greater impact.

Anticompetitive Scrutiny Of PPOs

It has been mentioned in the Section Introduction that a PPO can be seen as the vertical integration between upstream providers and downstream third-party payers. As it is well-known in the economics of regulation, vertical relations may jeopardize market competition. This is so in the private health care market as well.

In the UK, concerns on limits to competition in the provision of private health care, has prompted the Office of Fair Trading (OFT) to its scrutiny. In particular, attention is focused on the level of concentration among providers of private health care, barriers to entry, restrictions on the ability of medical professionals to practice, and consumers’ access to providers. The report appeared in December 2011 (the report can be downloaded at http://www.oft.gov.uk/shared_oft/market-studies/ OFT1396_Private_healthcare.pdf) led the OFT to undertake a public consultation on its findings which closed in January 2012 (see the associated press release in http://www.oft.gov.uk/news-and-updates/press/2012/26-12). A special report on this study has been published by Health Insurance in January 2011 (issue 158, pp. 14–15, see http://content.yudu.com/A1r4do/ HIJan2011/resources/index.htmreferrerUrl=), assessing the viewpoints of private hospitals and doctors, and insurers. They share aims but also face difficult trade-offs. Although insurers agree with hospitals and doctors on the need to guarantee prices and patient flows, they disagree on the patients’ capacity to choose among a variety of providers. Finally, hospitals and doctors align with insurers on preventing shortfalls but disagree on the meaning of ‘keeping costs at a reasonable level.’ The European Union antitrust authorities are virtually silent on anticompetitive issues around PPOs.

In the USA, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) acknowledges the changes occurring in the health care market place, so that antitrust enforcement is essential to guarantee the performance of a health care system based on the systems of delivery of health care competing for consumer acceptance. In its report of 2004, the FTC remarks that its activity addresses two basic questions. One refers to the current role of competition in health care and how it can be enhanced to increase consumer welfare. The second one deals with the way antitrust enforcement protects existing and potential competition in health care. Regarding the PPOs, two areas of activity of the FTC are highlighted: bundled discounts and network joint ventures. Bundled discounts refer to the combined sale of two or more products and services at a lower price than the sum of the prices of those goods and services when bought separately. An instance of bundled discount would be proposing discounts to insurers in tertiary services if the insurers made a PPO the sole provider for primary, secondary, and tertiary services. The proper test to prove the existence of bundling requires to show that the price of the bundle is lower than the seller’s incremental cost. This is not simple because antitrust laws do not provide clear guidelines.

Physician network joint ventures are under the scrutiny of the FTC because they may reduce and even eliminate competition among the participants in the venture, and they may rise impediments to effective competition among different networks or health plans operating in the same market. Some providers excluded from the network joint ventures have filed complaints of monopolization of the market. However, evidence to support such complaints is difficult to obtain.

A different phenomenon widely studied is hospital mergers. Besides the traditional arguments of enhance efficiency and market power, another motive behind hospital mergers is the improvement of the bargaining position against MCOs. Some empirical evidence suggests that most consolidation of competing hospitals favor price increases in their markets, so that the market power motive seems to offset the efficiency argument.

Silent PPOs

In the early 1990s in the USA, a practice started by which one health plan was selling or renting its provider network (and the network discount rates) to another insurer without the provider’s knowledge. This practice has been labeled as ‘silent PPO.’

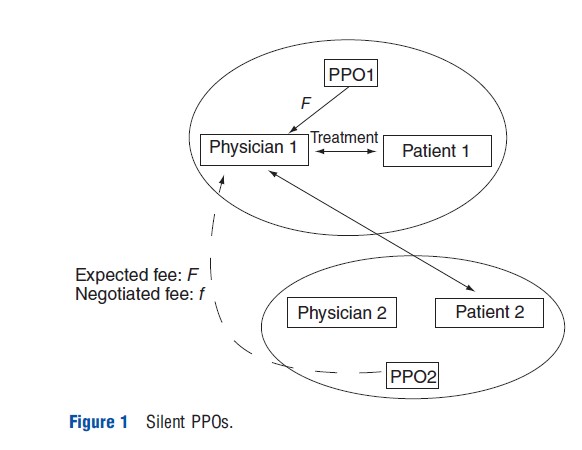

To illustrate, remember first that a physician’s reimbursement, when providing out-of-network services, is higher than the in-network fee. Now, consider a physician member of a certain PPO who receives the visit of a patient whose insurance company has no agreement with this physician’s practice. Typically, these insurers are organizations without networks of their own. Accordingly, the physician expects to receive the full bill charge from the patient’s insurer. The patient’s insurer when receiving the bill (and without the knowledge of the patient) assesses whether the physician belongs to a network with a negotiated discount. Then, it enquires about the possibility of the physician’s PPO allowing the patient’s insurer to use its negotiated discount (this is called the secondary discount market). If so, the physician receives a discounted reimbursement instead of the full payment for the treatment provider, so that even though the patient’s insurer does not belong to the PPO, it reimburses the health care services as if the physician would be an in-plan provider. In short, out-of-network services are reimbursed at in-network prices. Figure 1 illustrates the discussion considering a scenario with two PPOs. Physician 1 in PPO1 receives a fee f when treating an in-network patient, and expects a fee F>f when treating an out-of-network patient.

In principle, this need not be an illegal practice. It depends on the terms of the agreement between the insurer and the provider. Such agreements may contain an assignment provision allowing the health plan to offer the contract conditions to anyone willing to pay the agreed fees. Sometimes, there is written consent for the assignment to occur, sometimes there is no express consent or advance knowledge of the provider of such extension of the benefits to other health plans.

Initially, the term ‘silent’ PPO referred to a PPO where the contract was silent with regard to the commitment of the PPO to direct and encourage its patients to visit the in-plan providers. In the early 2000s however, the term changed to refer to improper and illegal practices. The American Medical Association (AMA), the American Hospital Association (AHA), and the American Association of Preferred Provider Organizations (AAPPO) have taken stance against these practices, and actively tried to encourage legislative actions against them. The problem arises because the providers (physicians and hospitals) realize the situation ex-post, once the treatment has been provided and billed. Accordingly, it falls in the hands of the providers to ensure that only patients enrolled in the PPO receive the discounted fees, whereas outside patients are billed the full price of the treatment received.

Final Remarks

Preferred provider organizations are the most popular forms of private provision of health care. It balances in the best way the trade-off between insurers and individuals on the one hand, and between insurers and providers on the other. That is, the freedom of individuals to choose providers and the terms of the insurance contract on the one hand, and the base of patients and the discounted fees on the other, with respect to other forms of managed care.

All these agents meet in the market place, where two features are of particular concern. The first one, the structure of PPOs vertically integrating upstream providers and downstream third-party payers, raises the inquiry from the antitrust authorities. The second refers to the degree of transparency of the terms of the contracts between insurers and providers that have promoted legislative initiatives to prevent the better informed party from taking advantage of imperfect information.

References:

- Barros, P. P. and Martinez-Giralt, X. (2002). Public and private provision of health care. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy 11(1), 109–133.

- Barros, P. P. and Martinez-Giralt, X. (2008). Selecting health care providers: ‘‘Any willing provider’’ vs. negotiation. European Journal of Political Economy 24(2), 402–414.

- Boonen, L. H. H. M. and Schut, F. T. (2011). Preferred providers and the credible commitment problem in health insurance: First experiences with the implementation of managed competition in the Dutch health care system. Health Economics, Policy and Law 6, 219–235.

- Boonen, L. H. H. M., Schut, F. T., Donkers, B. and Koolman, X. (2009). Which preferred providers are really preferred? Effectiveness of insurers’ channeling incentives on pharmacy choice. International Journal of Health Care Finance and Economics 9, 347–366.

- Capps, C. S. and Dranove, D. (2004). Hospital consolidation and PPO prices. Health Affairs 23(2), 175–181.

- Capps, C. S., Dranove, D., Greenstein, S. and Satterthwaite, M. (2002). Antitrust policy and hospital mergers: Recommendations for a new approach. The Antitrust Bulletin 47(4), 677–714.

- Eggleston, K., Norman, G. and Pepall, L. M. (2004). Pricing coordination failures and health care provider integration. Contributions to Economic Analysis & Policy 3(1), article 20.

- Federal Trade Commission (2004). Improving health care: A dose of competition. A Report by the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice. Available at: http://www.ftc.gov/reports/healthcare/040723healthcarerpt.pdf (accessed August 2012).

- Fuller, D. A. and Scammon, D. L. (2000). Antitrust concerns about evolving vertical relationships in health care. Journal of Business Research 48, 227–232.

- Gaynor, M. and Haas-Wilson, D. (1999). Change, consolidation, and competition in health care markets. Journal of Economic Perspectives 13(1), 141–164.

- Greany, T. L. (2007). Thirty years of solicitude: Antitrust law and physician cartels. Houston Journal of Health Law and Policy 7(2), 189–226.

- Hurley, R. E., Stunk, B. C. and White, J. S. (2004). The puzzling popularity of the PPO. Health Affairs 23, 56–68.

- Morrisey, M. A. (2001). Competition in hospital and health insurance markets: A review and research agenda. Health Services Research 36(1), 191–221.

- Steadman, K. A. (2006). Silent preferred provider organizations. What is all the noise about? FORC Journal 17, 4 ed., article 3.