With increasing globalization, countries have opened up their borders to trade in goods and services, often including health services. This has given rise to heated debates in the media and the academic and professional literature, with proponents arguing that it can improve efficiency and facilitate the sharing of ideas, although opponents argue that international trade in health services will result in increased privatization and hinder domestic decision making. In reality, lack of data makes it very difficult to ascertain the volume of trade in health services and the effect it is having on health systems.

There are different ways in which health services can be traded internationally, involving either patients or health professionals traveling to another country to obtain/provide health services, countries investing in other countries’ health services, and through the remote provision of health services. This article is concerned with the latter form of trade, the remote cross-border provision of health services, also known as international e-health, and its impact on the national health system of the countries involved in it.

The article reviews both the positive and negative contributions that international trade in e-health services may offer to national health systems. In doing this, it will briefly comment on the different types of trade relationships the countries may engage in, and in turn, how this can affect the impact international e-health has on their health systems.

This article is structured as follows. First, it defines e-health and outlines examples of its different uses. This is followed by an account of how national health systems of countries engaging in international e-health (both as exporters and importers) are affected by it e-health, before outlining the different types of trade relationship e-health can be traded under. The article concludes with key messages.

What Is E-Health?

E-health can be defined as the application of information and communication technologies across the whole range of health care services. Given that the scope of this article is on international e-health, it will be defined as the use of information and communication technologies to deliver health services across an international border.

Although traditional communication technologies can be used to deliver health services remotely – for instance, by using the postal service to send samples to be analyzed in remote laboratories – the term e-health is concerned with the use of nontraditional information and communication technologies. As it will be seen, most e-health services take place through the use of the Internet.

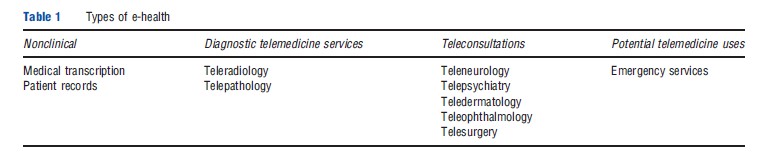

Table 1 shows the different uses of e-health, which can be clinical and nonclinical. Nonclinical health services include medical transcription, where doctors record their notes and these are transcribed remotely, often overnight, and electronic patient records. However, the most potential use for this type of trade in health services lies within the provision of clinical services. This is known as telemedicine. Telemedicine can be divided into different subsets, depending on the type of care that is provided, as shown in Table 1.

An important use of cross-border telemedicine is the remote provision of diagnostic services. The most popular of these has so far been teleradiology, where images, such as X-rays, are transferred electronically to radiologists remotely for interpretation. Teleradiology is often done across different time zones, which allows for images to be processed overnight, a process known as ‘nighthawking.’ Similarly, telepathology involves sending images of processed samples (such as microscope images) for interpretation.

A final (and emerging) use of telemedicine is to provide consultations at a distance. This can be done when the experts are physically located far from the patients. This practice has given rise to specialties such as teledermatology, telepsychiatry, and teleophthalmology, and has the benefit of permitting access to expertise to patients who would not have otherwise been able to travel for it. The use of cross-border provision of surgery and emergency services has been considered as a potential area of growth in the global e-health market, but its use has not been explored as yet in any major initiatives.

To What Extent Do Countries Engage in E-Health?

The size of the global e-health market is difficult to estimate, as there is currently no systematic collection of data on the amount of e-health trade that takes place or the revenues made from it. However, estimates in the literature indicate that it is happening on a large scale and generating significant revenues, with the global e-health market estimated to be worth between US$1 billion and US$1 trillion (Mutchnick et al., 2005). This lack of reliable data poses problems for health planners, as they are not aware of how much e-health trade is taking place, and for policy makers, who then base their decisions on ideology rather than evidence.

The size of the global e-health market is difficult to estimate, as there is currently no systematic collection of data on the amount of e-health trade that takes place or the revenues made from it. However, estimates in the literature indicate that it is happening on a large scale and generating significant revenues, with the global e-health market estimated to be worth between US$1 billion and US$1 trillion (Mutchnick et al., 2005). This lack of reliable data poses problems for health planners, as they are not aware of how much e-health trade is taking place, and for policy makers, who then base their decisions on ideology rather than evidence.

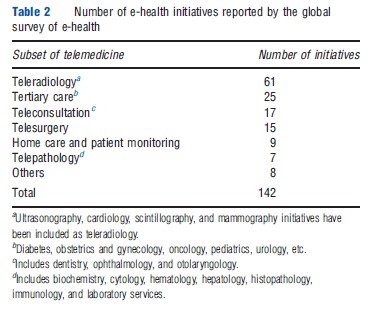

The World Health Organization’s Global Observatory for e-health conducted a global survey of e-health in 2009 to map out all e-health initiatives that are currently taking place across the globe. The results from this survey are summarized in Table 2; they include all e-health initiatives (national and international), so the true size of the international e-health market will be smaller.

Of these initiatives, teleradiology, some tertiary care, and telepathology are the areas that currently hold greatest promise for international e-health trade.

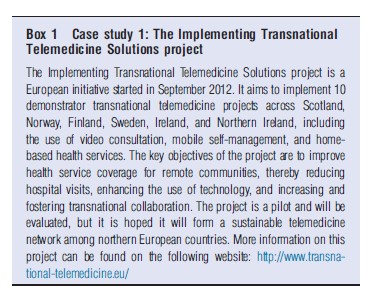

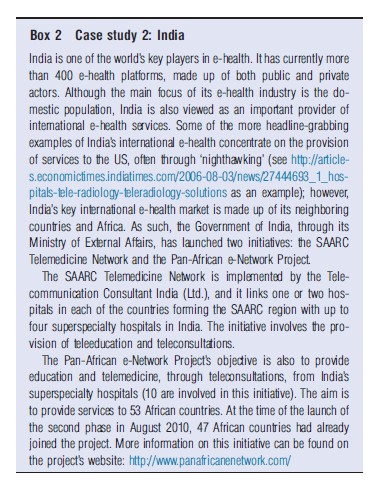

Although e-health is not bound by physical location, there are some factors that influence which countries trade with which, such as common language and data management protocols. This has resulted in a significant proportion of e-health trade taking place regionally. Examples of such regional trade initiatives are summarized in Boxes 1 and 2.

How Can Countries Benefit from International E-Health?

When discussing cross-border e-health trade, countries can be divided into ‘exporting’ and ‘importing,’ depending on whether they provide or ‘purchase’ e-health services, respectively. Exporting countries tend to be low- and middle-income countries, which have invested in technology and can provide services for a fraction of the cost of their higher income counterparts. The top three exporters of e-health services are India, the Philippines, and Cuba. However, the importing countries tend to be high-income countries, whose health systems are facing budget restrictions and efficiency calls. The USA is the top importer of e-health services. Given that the impact e-health has on countries is dependent on whether they are importers or exporters, it will be discussed separately.

Importing Countries

The most important benefit the importing countries stand to gain from outsourcing health care services to exporting countries is a financial one. This is because most exporting countries are low and middle income, and can therefore provide health services remotely for a fraction of what they would cost in the importing country, mainly due to the fact that the health professionals’ salaries can be up to 10 times lower. This is particularly relevant in the current financial situation, where many importing countries are facing budgetary restrictions and are looking to make their provision of health services more efficient.

The second means by which the importing countries can benefit from outsourcing health care services internationally is by decreasing the waiting time. The health systems of many high-income countries suffer from long waiting lists, particularly for elective procedures. By outsourcing some of their health services, such as diagnostics, the importing countries can significantly reduce waiting lists. In addition, the fact that the importing and exporting countries are often situated on different time zones allows for services to be carried out overnight, greatly improving the efficiency of the health care system in the importing countries. Furthermore, due to the importance of early diagnosis in certain conditions such as cancer, patients can be diagnosed and started on treatment sooner, which will lead to improved prognosis and lower costs.

A further advantage of engaging in e-health trade facing the importing countries is the improvement in coverage of remote areas. Remote populations are very expensive to serve and often hard to access. Therefore, providing the services remotely would greatly reduce costs and improve the quality of health care coverage of remote populations.

Finally, outsourcing of routine diagnostic and curative services to the exporting countries can reduce the workload of health care professionals in the importing country and allow them to concentrate on the more complicated cases and therefore, improve specialization and skill set in the country.

Exporting Countries

Exporting countries can also benefit greatly from engaging in international provision of e-health services. Similar to the importing countries, the key benefit is a financial one, as they can generate foreign income. As highlighted earlier, the e-health market is of substantial size; although no official figures are available, it is estimated that the telemedicine market holds a huge potential for the importing countries. For instance, in India, it is estimated to be worth h37.4 million, with projections to reach h374 million (Financial Express. Telemedicine: An answer to ailing India. 5 November 2007; http://www.financialexpress.com/news/telemedicine-an-answerto-ailing-india/236263/0). It can therefore particularly benefit the exporting country’s health system if it is invested back in it. This is of particular importance given that the exporting countries are typically low- and middle income and often have underfunded health systems.

Exporting countries can also benefit from providing e-health services by reversing their ‘brain drain.’ The brain drain is a phenomenon caused by health professionals migrating in the pursuit of higher salaries, improved quality of life and career prospects. It particularly affects the low- and middle-income countries, which suffer severe shortages in human resources for health. It is also some of these countries that have started exporting health services, such as e-health, and can therefore take advantage of the higher salaries and career opportunities the e-health posts offer to attract some of these workers back to the country and thereby increase their human resource base in the health sector.

To be able to provide e-health services to the importing countries, the exporting countries need to remain competitive and meet international standards. They therefore often make significant investments in technology and on improving the available skill set of their health workforce. This will also benefit the local population as the technology and health professionals available will unlikely devote all of their time to providing e-health services to other countries, and can then be used to provide domestic services, thereby providing the opportunity of using the international market to subsidize their domestic services. In fact, some of the key exporters of e-health services, such as India, have important domestic e-health services, with considerable potential for expansion.

What Do Countries Risk by Engaging in E-Health?

The section Exporting countries has highlighted the great potential that both importing and exporting countries have for benefiting from international e-health trade. Next, the risks these countries face when entering this type of trade in health services are discussed.

Importing Countries

The key risk the importing countries face when engaging in e-health trade is data security and privacy. Data sent over to the exporting countries are extremely sensitive in nature as they include health records, and there must therefore be absolute guarantee that confidentiality will be preserved. In fact this tends to be the main barrier to engaging in this type of trade, with countries only trading with those who have similar or trusted data management protocols.

In addition, the importing countries also face the risk that the quality of the services provided by the exporting countries would be lower than that they themselves can offer. This can be further compounded by language and cultural differences, as well as the different training the health professionals receive in different countries, which hinder the ability of health professionals to communicate with each other and the patients and agree on a course of action. A related concern is liability: Who is responsible if something goes wrong? If countries engage in e-health trade, malpractice will eventually occur, and when it does, it is not clear whose responsibility it would be. There are concerns that the importing countries would face expensive lawsuits, which would offset any savings made from e-health trade.

Finally, the importing countries risk job losses if some health services are performed in other countries. Furthermore, whereas allowing health professionals in the importing countries to specialize and concentrate on complicated cases is clearly an advantage, if all the uncomplicated cases are dealt with abroad, this may hamper the ability of new health professionals to be trained as they will not be exposed to them.

Exporting countries

Exporting countries also face some risks when providing international e-health services. Given the revenues to be made by providing e-health services to other countries, there is a risk that resources will be diversified toward this, at the cost of health services the domestic population needs. This may worsen rather than improve the national health system. In addition, if e-health services are provided through the private sector (as is often the case), the revenues generated may not be invested back into the health system.

Another risk the exporting countries face is the creation of an internal brain drain. The higher salaries and career opportunities offered by international e-health may not just attract health workers who had migrated, but also health workers currently employed by the public health system. This may actually exacerbate rather than ameliorate shortages in health professionals and again, worsen the domestic health system.

Trade Agreements

It is important to note that the potential risks and benefits countries face when engaging in e-health international trade outlined in this article are influenced by the type of trade relationship they engage in. There are three types of trade relationships countries can engage in: multilateral, regional, and bilateral. This section briefly summarizes each type of trade relationship and highlights how they can each influence the extent to which national health systems are affected by international e-health.

Currently, most e-health takes place under a multilateral system, where many countries trade with each other. This takes place under the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS), under the auspices of the World Trade Organization. The GATS categorizes services into four modes, which can all be applied to health services. Mode one covers the cross-border provision of services, which in the case of health would be e-health. Mode two involves consumption of services abroad (in the case of health medical tourism). Modes three and four deal with foreign direct investment (for instance, in a hospital) and the movement of natural persons (health care professionals), respectively. Under this form of trade agreement, countries can freely trade with others. The benefits and concerns described above mainly apply to the current system of multilateral trade, where it is more difficult to implement safe guards on data safety and quality of care and countries may find it difficult to define litigation procedures.

Cross-border e-health trade can also take place regionally. In fact, this seems to be the case in many instances. Countries are more likely to import health services from countries that have similar language, culture, and training standards. This has led to the development of different regional e-health initiatives, such as the Implementing Transnational Telemedicine Solutions project, the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) Telemedicine Network, and the Pan-African e-Network Project initiatives described in Case studies 1 and 2.

The final type of trade relationship countries may engage in when importing/exporting e-health services is a bilateral one. This would take place between two countries, an exporter and importer, where a contract would be drawn between the two outlining conditions under which trade will take place. The benefits outlined above would still apply to this type of relationship. However, there is potential to capitalize on them, for instance, by stating clearly in the contract what proportion of the revenues has to be invested back into the health care of the domestic population of the exporting country. Furthermore, some of the risks can be averted or reduced. For instance, the contract can state what data management protocols will be used, the minimum-required qualifications of the providers, and a program for the exchange or training of human resources to alleviate shortages in the exporting country. Despite these apparent benefits, bilateral relationships in e-health (and health services more generally) tend to be underresearched and underutilized.

Conclusion

This article has covered the definition and different uses of ehealth before outlining how countries – and their health systems – stand to gain or risk losing from engaging in this type of trade. The article then briefly reviewed the different types of trade relationships and how these can affect the impact international e-health trade has on both the importing and exporting countries. It is important to emphasize the dearth of data on e-health trade (and trade in health services in general), which makes it difficult for the health planners to plan their services, and base their decisions on ideology rather than evidence. Notwithstanding this, countries considering whether to engage in international e-health should consider bilateral initiatives, as these offer the possibility of controlling some of the risks, while still reaping the benefits from this type of trade.

References:

- Mutchnick, I. S., Stern, D. T. and Moyer, A. (2005). Trading health services across borders: GATS, markets and caveats. Health Affairs W5, 42–51.

- Blouin, C., Drager, N. and Smith, R. D. (2005). International trade in health services and the GATS: Current issues and debates. World bank, Washington, D.C.

- Chanda, R. (2002). Trade in health services. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 80(2), 158–163.

- Gerber, T., Olazabal, V., Brown, K. and Pablos-Mendez, A. (2010). An agenda for action on global e-health. Health Affairs 29(2), 233–236.

- Khan, H. A., Qurashi, M. M. and Hayee, I. (2008). Better healthcare through telehealth. Commission on Science and Technology for Sustainable Development in the South. Islamabad: New United Printers.

- Lougheed, T. (2004). Radiologists get that long distance feeling. Canadian Medical Association Journal 170, 1523.

- Mars, M. and Scott, R. E. (2010). Global e-health policy: A work in progress. Health Affairs 29(2), 237–243.

- Martınez A´ lvarez, M., Chanda, R. and Smith, R. D. (2011). How is telemedicine perceived? A qualitative study of perspectives from the UK and India. Globalization and Health 7, 17–24.

- McLean, T. R. (2006). The future of telemedicine & its Faustian reliance on regulatory trade barriers for protection. Health Matrix 16(2), 443–509.

- Scott, R. E. (2009). Global e-health policy: From concept to strategy. In Wootton, R., Patil, N. G., Scott, R. E. and Ho, K. (eds.) Telehealth in the developing world, pp. 55–67. Ottawa: International Development Research Centre (IDRC).

- WHO (2010) Telemedicine: Opportunities and developments in member states: Report on the second global survey on eHealth 2009 (Global Observatory for eHealth Series, Volume 2). Available at https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44497/9789241564144_eng.pdf.