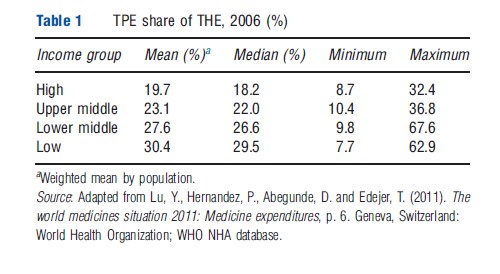

Pharmaceuticals used to treat a variety of health conditions continue to be a critical aspect of quality healthcare. However, consistent access to medicines in many low- and lower-middle income countries persists as a major challenge. Although there has been a global increase in proportion of gross domestic product (GDP) spent on health, there are significant inequalities in the spending on pharmaceuticals across countries. When looking at the share of pharmaceutical expenditures to total health expenditure (THE) by country income group, one can see large differences between the mean spending in high- income countries, compared to low-income countries. This may be reflective of multiple factors including disease burden, health system infrastructure, differences in cost of service delivery and health policies (Table 1).

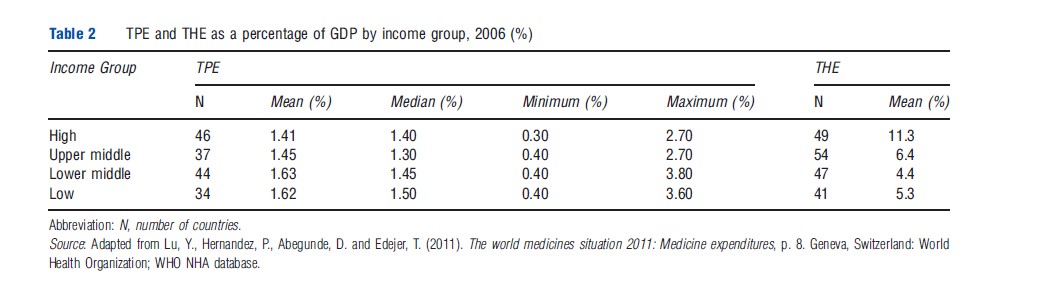

In 2006, 1.5% of the global GDP represented pharmaceutical spending. Pharmaceutical expenditures are negatively associated to GDP by income group with total pharmaceutical expenditure (TPE) as a share of THEs ranging from a mean of 1.41% in high-income countries to a mean of 1.62% in low- income countries. Lower-income countries spend a greater percentage of their total health costs on pharmaceuticals relative to their GDP (Table 2).

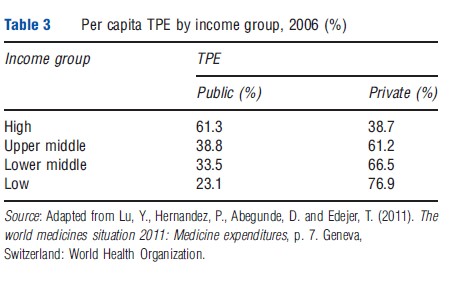

Further, among lower-middle and low-income countries, the private sector is where a large share of pharmaceutical expenditures are made. A considerable portion of this spending is based on a community’s ability and willingness to pay for health products. In many low- and middle-income countries numerous individuals purchase pharmaceuticals using out-of-pocket (OOP) monies. Up to 50% of THEs are made using OOP monies of which, up to 90% go toward the purchase of medicines. The opposite trend appears to be true for high-income countries where health insurance and other financing or pricing policy may be in place (Table 3).

According to IMS Health, the largest segment of global spending growth for pharmaceuticals is expected in pharmaceutical markets in emerging economies such as China, Brazil, India, Russia, Mexico, Turkey, Poland, Venezuela, Argentina, Indonesia, South Africa, Thailand, Romania, Egypt, Ukraine, Pakistan, and Vietnam or pharmaceutical markets in emerging economies. Population growth, new healthcare reforms, and economic growth are expected to increase spending in these markets. In 2006, global spending on pharmaceuticals within pharmaceutical markets in emerging economies was 14% compared to developed markets including the European Union, Japan, the US, Canada, and South Korea. In 2011, this share increased to 20% and in 2016, it is predicted to increase to 30%. Given the forecasted increases in global spending, ensuring consistent access to medicines will remain a central focus for healthcare stakeholders. This article will outline the traits of pharmaceutical sectors within low- and lower-middle income country health systems. Further understanding of these system traits will enable strategic reform and improvements in this sector.

Pharmaceuticals And Health Systems

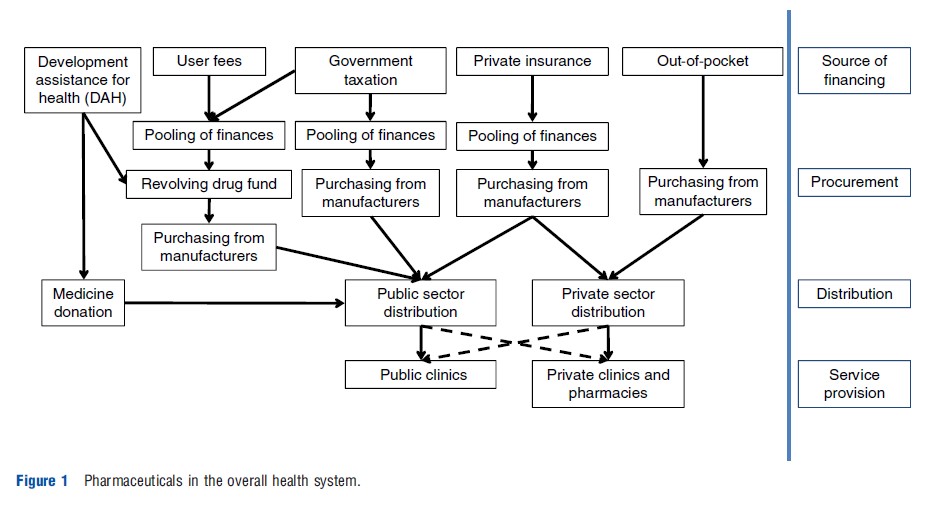

Health systems vary in form, but irrespective of the form of the health system, pharmaceuticals play a critical role within it to prevent and treat health conditions. It is important to understand the organization of each country’s pharmaceutical sector in order to ensure consistent access to pharmaceuticals. Elements of financing, procurement, distribution, and service provisions must be effectively aligned to reach patients with medicines. Each of these components contributes to the overall effectiveness and efficiency of the health system.

Efficiency in a health system is a metric by which performance may be measured. Health system efficiency includes both technical efficiency – the method for producing a good or service at minimum cost – and allocative efficiency – the right collection of outputs provided in a health system to achieve overall health improvement goals. Evidence shows that in health systems with similar health expenditures per capita, technical and allocative efficiency help explain differences in population health outcomes (Figure 1).

Technical efficiency of the pharmaceutical subsystem within national health systems implies achieving best pharmaceutical related health outcomes at the lowest cost. The degree of technical efficiency varies with the structure by which financing is collected and potentially pooled to be used to procure medicines. For example, pooling arrangements may optimize technical efficiency of national health systems through the purchase of larger volumes of medicines at the most competitive prices. Allocative efficiency for pharmaceuticals in national health systems consists of product selection and resource allocation decisions that ensure medicines of greatest need and health benefit are available.

Technical efficiency and allocative efficiency couple together sustainability and equity goals of the health system. Further discussion of the elements impacting health system efficiency will be reviewed in individual detail in the sections that follow.

How Are Pharmaceuticals Financed?

In the overall health system the financing function typically: (1) collects revenue from multiple sources, (2) pools funds and spreads risks across groups, and (3) allocates funds to purchase goods and services. Within the general structure of health financing, pharmaceuticals may be financed through a variety of mechanisms.

Out-Of-Pocket Spending

OOP spending typically makes up a large portion of financing for medicines in developing countries. Individuals make OOP payments most often for outpatient and chronic care. Spending of this kind typically impacts lowest income households, usually part of the informal economy, to the greatest degree. OOP can account for up to 50% of total healthcare expenditure in low- and middle-income countries, whereas in higher income countries this amount is estimated to be much less (approximately 15%). Of OOP expenditures, up to 90% are spent on medicines.

OOP spending may be individually financed from personal savings or through borrowing funds and accepting debt. In a study of 15 African countries done by Leive and Xu in 2008, approximately 30% of all households surveyed financed their OOP health expenditures by borrowing or selling assets. This form of healthcare financing is largely dependent on the populations’ willingness and ability to pay for medicines.

Private Prepaid Funds

Prepayment of healthcare services and medicines is another financing mechanism available in certain contexts. Prepayment schemes are usually managed by health plans within countries. For example in South Africa, a separate healthcare company Yarona Care has developed prepayment schemes at discounted rates. Patients may purchase vouchers in advance for their expected health needs and redeem them throughout the year. Vouchers are priced to save community members money and guarantee them a network of quality service providers. This system presumes individuals have sufficient funds and are willing to pay for services in advance. Within populations with a high burden of chronic diseases, the expectation to pay for services and medicines throughout the year may be greater. Within populations with fewer long- term conditions to manage (or poor awareness and few available services for such conditions) and/or a larger emphasis on episodic care, individuals may be less inclined to purchase care in advance as their expectations for healthcare costs may be less certain.

The prepayment method of healthcare financing provides a structure to help improve healthcare resource allocation and planning at an individual level. It may also integrate technology to minimize administrative management and associated costs of voucher utilization as with the South African care model.

Revolving Drug Funds

Revolving drug funds (RDFs) involve a one-time investment of capital utilized to develop a self-sustaining medicine supply system. In low-income countries capital funds are often provided by external organizations as part of development assistance for health (DAH). Once established, RDFs are reimbursed through the sale of drugs. Funds are pooled before placing new orders of medicines directly with suppliers. RDFs create a consistent pool of monies with buffer financing to ensure timely procurement of essential medicines and consistent access for patients. RDFs act as a separate fund of money protected from fluctuations in available government resources and shifting political priorities. A fund of this nature does necessitate its own administrative management as well as cooperative coordination between invested stakeholders and funders. RDFs are a financing strategy utilized by multiple national healthcare systems in low- and lower-middle income countries to promote access to medicines.

Ensuring success of an RDF requires thoughtful consideration of the country context. Previous research has outlined a set of guidelines essential for a successfully implemented RDF. Where elements are lacking within these guidelines, further preparation or planning may be required before establishment of a revolving drug fund and/or alternative methods for improving access should be examined.

Private Insurance

Private healthcare insurance is typically paid for or provides care directly to employees by their employment firm. Employers offer insurance as a benefit to their employees, however, employees typically still pay copayments on medicines and premiums for services. The risk pooling that takes place is usually dependent on the size of the employer and/or the size of the insurance company offering a health plan to the employer. Employee-based insurance plans are less common in lower and lower-middle income countries as many individuals work in the informal economy.

Private health insurance funds, separate from employersupported insurance are voluntary and typically less common in most developing market contexts. Individuals contract with an insurance entity that pools the risk of all members. In general, individual private health insurance funds have low membership, low contributions, low coverage and weak regulatory environments. Private health insurance may be organized as a nonprofit entity or a for-profit entity. Typically nonprofit entities charge premiums just as for-profit entities. Nonprofit insurance plans are often arranged by religious groups, civic groups, hospitals and physician associations. Namibia and South Africa represent two countries where private-for-profit health insurance is relatively common. Private-for-profit health insurance providers represent the predominant prepaid plans in these contexts. For-profit insurance plans are funded through equity from private stakeholders as well as premium payments by enrollees. Uptake may be low as a result of the inability to afford annual fees and/or the perception that services and practitioners available for service are poor quality and so advanced payment is seemingly less appealing. Individuals may rather purchase healthcare only when necessary in these instances.

Community Health Insurance

Community-based health insurance (CBHI) is a voluntary insurance mechanism in which an organization coordinates a community of payers in order to pool risk to cover all or part of healthcare costs. At times, the organization may be a buyers’ cooperative managed by representatives of the community. Studies examining the impact and effectiveness of CBHI in low-income countries have found that there is little evidence to support community-based insurance as a viable healthcare financing mechanism. Although successful in certain specific contexts, in general CBHI is not able to sufficiently mobilize financial resources. There is some evidence that suggests CBHI relieves some of the burden of OOP for patients and increases utilization of healthcare. Even with CBHI, ensuring benefits reach the lowest income community members continues to be a challenge in healthcare financing. This is a specific population group where access to care is only marginally affected by CBHI as many individuals cannot afford premiums or contributions to the insurance scheme.

In general, CBHI does not address barriers to accessing health care (i.e., affordability, perceptions of care quality, and geographic distance to healthcare facilities). Additionally, reimbursement processes tend to be burdensome for plan participants. Certain specific examples demonstrate that dropouts of CBHI membership are common. The result of this is a smaller risk pool, which may in turn have a negative impact on the attractiveness of the health plan and future enrollment. Further research is needed to systematically summarize the characteristics of contexts where CBHI has shown a larger impact.

Social Health Insurance

Social insurance plans are a universal coverage health financing program in which membership is required for a population and members are provided a nationally determined benefit package of care. The World Health Organization has recently promoted social health insurance (SHI) plans as a means to reduce the burden of OOP on lower-income community members. Social insurance programs are typically financed through mandatory contributions from workers, self- employed, enterprises, and government. Most programs determine levels of contribution based on income along with contribution ceilings. Unemployed individuals within certain contexts are typically covered by others’ contributions or by government assistance. Health risks are typically pooled across larger populations than with community-based insurance programs and private insurance (employer-based, nonprofit, and for-profit) programs and over a longer period of time in lower- and lower-middle income countries. A prerequisite to SHI is having a sufficient portion of a given population participate in the formal economy. In lower- and lower-middle income populations that have larger informal economies, payments into a national SHI may place a higher burden on the formal economic members.

The costs of running a SHI program are greater, with complex administrative, allocative and accountability mechanisms. Variations of SHIs exist across Europe, Latin America, and parts of Asia where the programs have been instituted. In these contexts, entire populations are included for coverage or coverage may be more selective with medicine coverage provided to a portion of individuals. Some SHI arrangements allow for individuals to opt out voluntarily whereas others cannot afford to include all individuals and so selectivity becomes financially necessary. Social insurance programs typically determine a formulary of covered services and essential medicines which the program will finance. These lists are often based on World Health Organization (WHO) recommended essential medicines, however, updates to lists may be slow with access to medicines potentially lagging behind healthcare need.

Taxation

This form of financing is collected in large pools of funds that are not controlled by consumer payments. For members of the formal economic sector, indirect taxation through purchases and direct taxes on income may be an effective way to collect revenue to fund public healthcare. Indirect taxes may include taxes of goods or services (e.g., alcohol or tobacco purchase taxes) or taxes on lotteries and betting. Direct taxes are typically taxes on personal income, business profits and transactions, imports and exports, and property. A portion of taxes is typically allocated to healthcare through the ministry of health.

Balance Of Power In Procurement: Manufacturer, Payer, And Patient

In national procurement arrangements the balance of power between manufacturers and purchasers is more often seated with the manufacturer especially for patented medicines. For medicines that are only available from a single source (i.e., patented products or in some cases single registered manufacturer in the country), both pricing (i.e., affordability) and production (i.e., availability) are influenced to a great degree by the decisions of the monopolistic manufacturer.

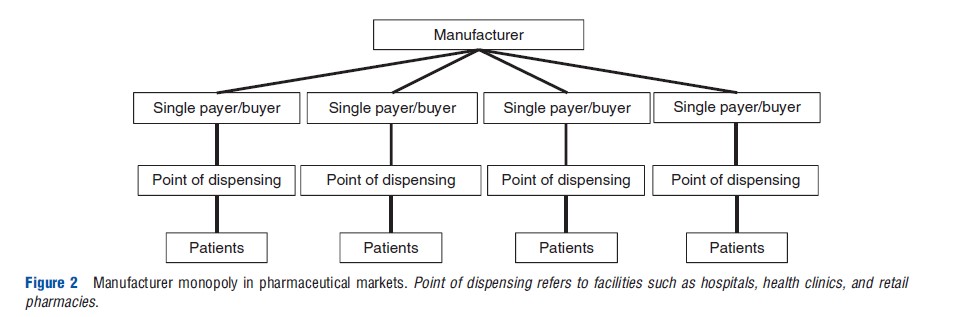

In developing country markets there is often fragmentation of orders among multiple purchasing groups. This results in lack of coordination and significant wastage of resources (Figure 2).

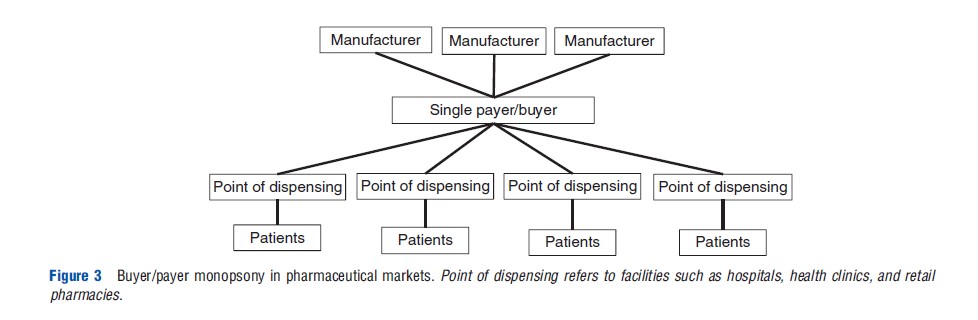

In some instances the opposite may also be true (i.e., a single large buyer has influence over supplier(s)). In contexts where one group is responsible for the majority of purchasing for a specific product, the single buyer may be better able to negotiate prices with the manufacturer. With multisource products (i.e., products with more than one manufacturer supplying to the market) the purchasing body achieves the best possible prices (Figure 3).

In Australia and many countries in Europe, government is the principal payer for pharmaceuticals and the market resembles a monopsony. In Australia, the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) selects appropriate pharmaceutical reimbursement levels. In the US, Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) help align the balance of power between manufacturers and purchasers. PBMs provide services to health plans including price discount negotiation with retail pharmacists, rebate negotiation with manufacturers, and managing mail-order prescription services and claims processing systems. PBMs also help health plans develop appropriate medicine formularies, review prior authorization for specific products and substitution scenarios for generic versions of brand name drugs. In their relationships with both retail pharmacies and pharmaceutical manufacturers, PBMs manage payment for retail and mail order drugs. Acting on behalf of health plans, PBMs have been able to obtain discounted prices and improved process efficiencies. In other country contexts, more than one, but still a small number of payers may purchase from suppliers. This would most closely resemble a monopsony with the balance of power still with the payers; however, a continuum of different procurement scenarios and related balances of power exist between the two extremes, monopoly and monopsony.

In many low and middle-income countries pooled procurement creates a balance of power between buyers and suppliers. These procurement arrangements influence affordability and the end patient price of drugs by pooling orders at a global level from multiple groups or countries and negotiating orders through bids from multiple suppliers. Pooling arrangements may take place within country or across multiple countries. Various pooling schemes are outlined in the section that follows.

Pharmaceutical Procurement And Distribution In The Public Sector

Medicine purchasing within the public sector may take place in multiple ways. Typically, procurement of medicines is based on epidemiological needs, funds availability, and sales and stock information collected from service facilities. Many countries rely on a registered list of essential medicines to determine which pharmaceuticals ought to be procured or reimbursed. Procurement varies based on the health system context and in many countries where health infrastructure continues to evolve so too does the procurement and distribution architecture. In health systems that are more centralized, often in geographically smaller countries, procurement is typically done by the ministry of health or a centralized agency acting on behalf of the ministry of health. In health systems that are decentralized, often larger countries with more extensive healthcare infrastructure, procurement of pharmaceuticals may be appropriated to the state or equivalent regional level.

National Pharmaceutical Procurement

Brazil provides an example of decentralized procurement of medicines. In Brazil, the Regulatory Council of the Pharmaceutical Market (CMED) approves medicines prices and adjusts products available on the market annually. The CMED helps to regulate purchasing prices paid by the government for medicines included in the Ministry of Health’s essential medicines list. Procurement within the Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS) is entirely decentralized and performed by the Federal Union, 5564 municipalities, 26 states and the Federal District. Current evidence suggests that this fragmented administrative structure although allowing certain flexibilities may lead to allocative inefficiencies of financing. Specifically, in municipalities with smaller populations, procurement of medicines is often more expensive because of lower negotiating power on smaller quantities purchased.

Several strategies have been recommended to mitigate these procurement inefficiencies including development of pharmaceuticals in public production laboratories, creation of consortiums of municipalities to engage in small-scale pooled procurement, predetermined pricing regulation that is consistent across states and centralization of purchases for pharmaceuticals at the national level for products manufactured by single provider and/or those that have the most expensive pricing and/or products that require importation. Of these strategies, municipal consortiums for medicine procurement have been implemented and examined in southern Brazil. The Intermunicipal Health Consortium (CIS-AMMVI) improved access to medicines by reducing the purchase price and the number of stock-outs. These benefits may impact smaller municipalities most as they are able to reach economies of scale and better negotiate prices in a larger tender process.

Similar to the strategy to set pricing standards across states or equivalent regions, Mexico has implemented the Coordinating Commission for Negotiating the Price of Medicines (CCPNM) and other health inputs. This national-level entity coordinates across public health institutions to collect background information including economic documentation to assist in annual negotiations for public procurement prices for patented medicines. Pricing negotiations are reported to save the country substantial financial resources; however, the political will and sustainability of this group may be less certain in the future. A coordination commission of this nature requires ongoing political support, appropriate performance indicators, and predetermined methods for assessing impact and transparency with key stakeholders.

Several centralized procurement models were setup in India at the state level to ensure consistent access to medicines. The Delhi Model Drug Policy pooled procurement for all hospitals within the state with a storage and distribution center. This policy not only organized procurement but it also pushed for implementation of standard treatment guidelines and a standard essential list of medicines, which fed into the development of a formulary for the state. In addition, a nongovernmental organization (NGO), Delhi Society for the Promotion of Rational Use of Drugs (DSPRUD) was contracted to implement technical activities related to the state policy. The Delhi model was largely seen as a success increasing access to medicines in many government hospitals.

Similarly, in Tamil Nadu, the state instituted a centralized drug purchase organization, the Tamil Nadu Medical Services Corporation Limited (TNMSC). TNMSC was developed to create a systematic method for streamlining the purchase, storage, and distribution of essential medicines in the public sector. TNMSC setup information systems including the provision of computers to warehouses for tracking stock in and out of storage and passbooks at clinics and hospitals to record inventory received. The TNMSC procurement gave structure to the previously fragmented purchasing structure. It laid out guidelines for the selection of suppliers, payment procedures, and standard essential medicines. This pooling mechanism has helped to purchase medicines at lower prices and to better ensure consistent availability of products. This model is now being used as a national benchmark for centralized procurement within each Indian state.

Centralized pooling of procurement for pharmaceutical products increases the level of influence a community of buyers may have on suppliers. Pooling higher volume orders enables suppliers to reach more efficient production at economies of scale. Buyers are better able to realize these efficiency savings because they are aligned and can negotiate in a unified fashion for lower prices. Pooling may also provide benefits to suppliers as they will be provided with a forecast of demand from a larger community of purchasers rather than relying on each individual tender. As a result, they may be better prepared with installed manufacturing and supply capacity to serve the needs of their buyers. However, in nationally centralized systems the administrative and management costs required to ensure information is collected and pooled in a timely fashion may be challenging and complex. Decentralized purchasing creates more flexibility among purchasers to order whenever necessary. The result is a procurement system that is more responsive to fluctuations in demand and may be better able to prevent stock outs. The tradeoff between the flexibility of decentralized purchasing and lower prices obtained through centralized purchasing should be considered according to each context.

Global Pharmaceutical Procurement Groups

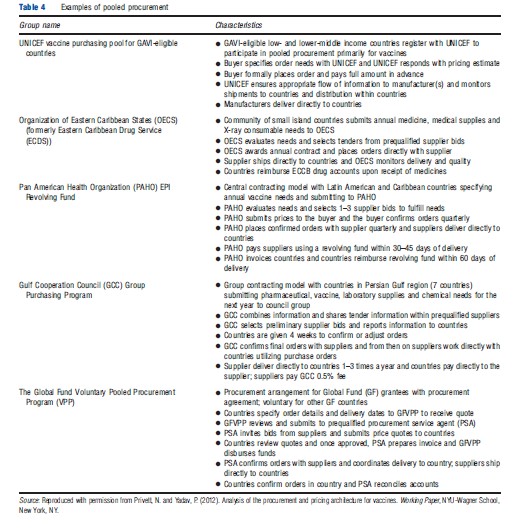

Global pooled procurement of medicines enables countries to negotiate contracts with suppliers at the global level. As with pooling within countries, pooling orders across countries provides smaller countries or countries requiring fewer medicines for specific diseases with increased negotiating power. Joint procurement arrangements typically involve an organizing, intermediate buyer. Often, donor agencies will help facilitate this intermediate step either by setting up a new intermediary buyer as the Partnership for Supply Chain Management in the case of President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief or working with existing procurement groups as with vaccines for GAVI-eligible countries procured through United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) (Table 4).

Multiple actors in the pooling mechanism may introduce the same inefficiencies and delays in payment and shipments as with traditional individual tenders. In certain pooling arrangements, revolving funds are used to address delayed payments from buyers to ensure payment is assured to suppliers and medicines are received as needed. Revolving funds require additional management and may be relied on too heavily to fill in financing gaps. Global pooling arrangements may not be best suited to all contexts. Countries with limited domestic resources to purchase medicines (highly resource constrained) as well as contexts with large purchasing volumes and thereby individual purchasing power (i.e., Brazil, India, China) may not be well-suited to a multicountry pooling mechanism.

Setting Prices/Price Ceiling Or Reimbursement Levels For Pharmaceuticals

Because pharmaceuticals constitute a large portion of the overall health expenditure, payers and governments use different levers for managing the prices of pharmaceuticals. The exact nature of the method used depends on the way the overall health system is organized.

The most direct form of controlling prices is a statutory price control used at the ex manufacturer, wholesaler, retailer, or some combination of these levels in the distribution chain. Most countries in Europe, Australia, Canada, and many Francophone African countries use such an approach. In many instances the health authorities set a price for a medicine based on the prices for that product in other countries in its region, income class, or countries with other similarities. For example, the prices in Greece are selected to be the average of the three lowest prices in the European Union (EU). In some countries medicine prices are set based on a comparison with medicines that have similar active substances. In India the price of a select group of medicines (scheduled drugs) is regulated whereas others are not regulated. Indonesia, South Africa, and many other lower middle-income countries also have such schemes.

Most countries in the EU regulate their wholesalers and retailer margins in addition to control on ex manufacturer prices. The wholesaler and retailer markup regulation takes multiple forms such as fixed percentage markup, fixed absolute markup, and regressive markup (i.e., the markup decreases with increases in the product price resulting in incentives for the channel to also stock and promote lower cost products). For example, in Spain for products with a selling price lower than h22.90 the wholesale margin is 10.3% of the price; for products priced higher than h22.90 and lower than h150, a margin of 6% on the portion of the price higher than h22.90 is charged; and for products above h150 a 2% margin is allowed on the part of the price over h150. South Africa and India use a single exit price regulation where the retail price is set once the price negotiations with the manufacturer are carried out.

A less direct form of price control is through the use of formularies, which specify which drugs will be used for which condition and the price to be paid for it. In return for putting a drug on the formulary the payer (insurance company or hospital) asks the pharmaceutical company to offer discounted prices. In some cases these pricing negotiations are carried out on behalf of the payer by specialized organizations called PBMs.

Some countries such as the United Kingdom (UK) and Australia also use pharmacoeconomic assessments and health technology assessments (HTAs) to set the prices of new medicines. This involves a cost–benefit analysis of the new medicines relative to existing treatments. Based on HTA, recommendations are made on the price and reimbursement level for the medicine evaluated. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) of the UK is a pioneer in the use of such techniques.

More recently risk-sharing between the manufacturer and the payer is gaining ground in some countries such as the UK. Under such arrangements the pharmaceutical company gets a smaller price/reimbursement level at the start and as health outcomes are realized from the use of the product the remaining reimbursement is made. These are like payment by result schemes where part of the payment is based on outcomes achieved in practice. Numerous examples exist, but a noteworthy one is where the pharmaceutical company agreed to pay NHS if the product atorvastatin failed to reduce LDL-C levels to agreed targets and a risk-sharing program for Borte-zomib used to treat multiple myeloma.

Domestic Production Versus Import Of Pharmaceuticals

Economic And Public Health Views On The Issue Of Pharmaceutical Access

Domestic production as a strategy to increase access through the reduction of production and shipping lead times, decline in importation costs and the development of the local economy is an important component of the ongoing debate around improving access to medicines. Within this discussion there is often tension between economic interests and public health interests. Domestic production of pharmaceuticals is thought of as a means to create new jobs and increase the skill-level of local communities. However, this industrial economic argument for local production may sometimes be at odds with public health interest to improve access, both availability and affordability, of medicines. If quality medicines cannot be produced efficiently and cheaply in the local context, local production may not be the best investment of resources.

It is reasonable to expect that countries would want to become self-sufficient with their production, especially as they have seen domestic pharmaceutical industries developed in other developing country markets (i.e., India, China, Brazil, South Africa). However, historical examples should be considered with thorough understanding of the current realities of global trade, regulation, international economics of the pharmaceutical industry as well as the aforementioned assumed tension between economic and public health interests. Global trade, more specifically patent policy as a part of the Trade Related aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) agreement, has been cited by many as a complex, resourceintensive area to navigate for developing country governance structures. Context-specific information will help to establish the case for national manufacturing self-sufficiency when appropriate.

Domestic Production Business Models

Pharmaceutical companies in low- and middle-income countries are broadly organized into four main business models. The first is a pharmaceutical subsidiary of a large multinational company. The locally situated business will manufacture branded products for local and regional markets. The second business model consists of generic manufacturers producing a large portfolio of generic drugs for the global market. These drugs typically meet global quality standards and are competitively priced. The third business model consists of domestic generic manufacturers with a national focus on operations. Most manufacturers that fall into this category produce drugs for their country of residence or neighboring countries. Some, but not all manufacturers meet good manufacturing practices (GMP) standards for their products. Small-scale local manufacturers make up the fourth business model. These manufacturers typically serve local or regional markets and often do not meet GMP standards. Sometimes, small-scale manufacturers may be owned or managed by a local NGO or large hospital group. The portfolio of medicines produced is often focused on fewer drugs.

In addition to the aforementioned business models, domestic production of drugs may be setup as a combination of models. The level of production in locally situated manufacturing facilities may also vary based on the governing business model. Typically, most domestic production of medicines in low- and middle-income countries focuses on formulation and packaging of products. Chemically synthesized products (i.e., the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API)) are typically purchased and imported for local formulation into a complete product. Chemical synthesis tends to be a more complicated process; however, many generic manufacturers serving the global market are able to produce APIs for sale to others and/or as a part of their drug production. At any level of production pursued by domestic manufacturers, large capital investments are required up front to finance initial production facility development and technology transfer. Joint ventures like Cipla Ltd. Joint venture with Ugandan manufacturer Quality Chemicals and GlaxoSmithKline’s joint venture with South African manufacturer Aspen may provide some examples of ways domestic production may begin in new developing country markets.

Domestic Production Decision-Framework

The decision to pursue domestic production versus importation of medicines is dependent on quality costs, regulatory costs, size of the local market, competitiveness within the local market, availability of skilled manpower, and economic status of the country. In certain contexts, domestic production does not make economic sense and investments would be better made elsewhere (i.e., investment in healthcare infrastructure or stimulation of the existing local market). Successful domestic production requires a functional ecosystem to support business sustainability. An active national regulatory authority is needed to manage quality reviews and enforcement of standards. Further, international trade regulations may require additional investment of resources, both time and money, to compile with global policy. To cover initial capital costs related to regulatory requirements and installation of capacity, significant market share and sales volumes are needed to reach economies of scale. Without these elements, domestically produced drug prices may remain high and will struggle to be competitive both locally and globally. To address the issue of access to medicines through domestic production, countries should conduct a thorough market analysis considering the current business ecosystem. Batson, Evans and Milstein developed a framework that may be used for pharmaceuticals and vaccines to determine the production model that works best given a country’s market size, GDP per capita income and current technical capacity.

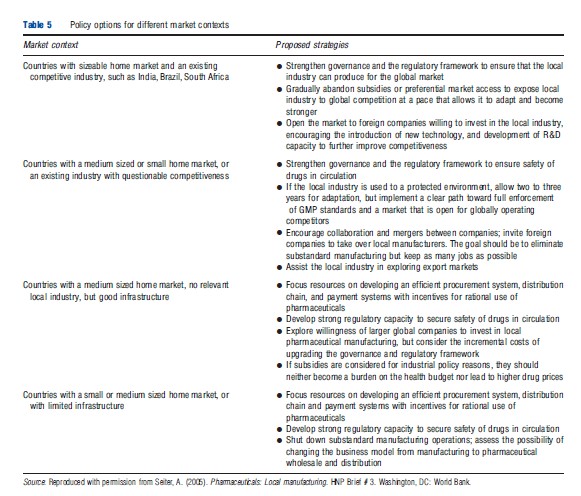

Similarly, strategic policy options, similar to those Seiter outlines for different market contexts should be considered to create the appropriate mix of domestic investments (Table 5).

How Are Medicines Distributed?

Medicine distribution may take place through supply systems that are run by governments or the public sector, the private sector and NGOs or faith-based organizations (FBOs). Within each of these supply chains, characteristics such as the type of commodity, geography, flow of finances, cost of commodities, public versus private treatment seeking will be different based on the country context. Generally, procurement, distribution and provision of pharmaceutical goods are managed across groups with involvement from public, private, and NGO/FBO sectors.

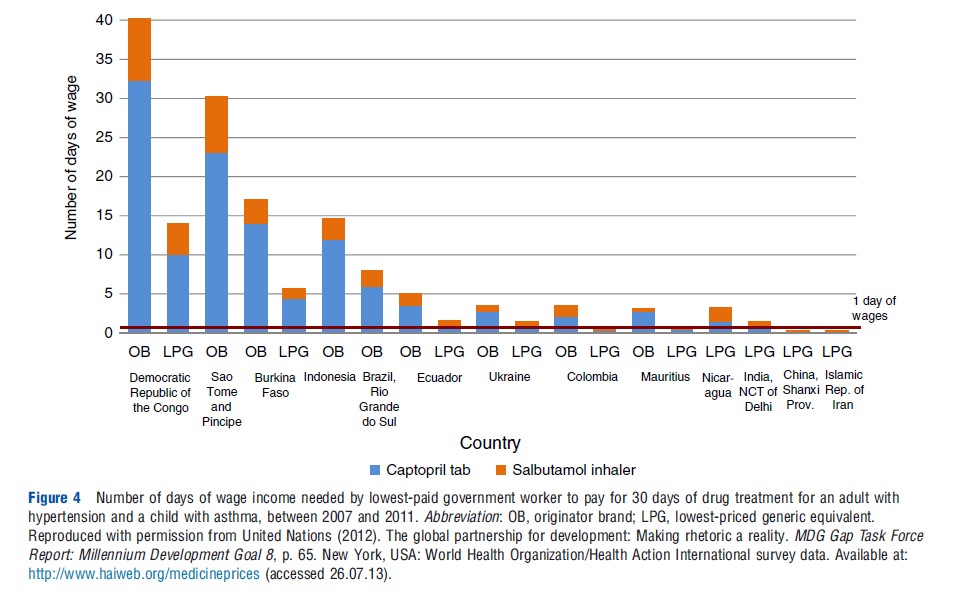

Private Sector Distribution

Private sector supply chains for medicines typically include a network of importers, wholesalers, sub wholesalers, pharmacies, and drug stores. In most emerging markets, pharmaceutical manufacturers sell products to national importers and wholesalers. Beyond the national level, there are often a large number of intermediaries between manufacturers and patients (wholesaler, sub wholesaler/stockist, retailer). Many private sector wholesaler networks struggle to reach more remote communities and so they rely on others to increase their distribution networks. Markups at each tier of the supply chain results in higher overall markups on medications. As a result, a complicated private sector distribution chain may negatively impact affordability to the patient. This may in turn impact a manufacturer’s ability to increase sales volumes and once economies of scale have been met, lower price points (Figure 4).

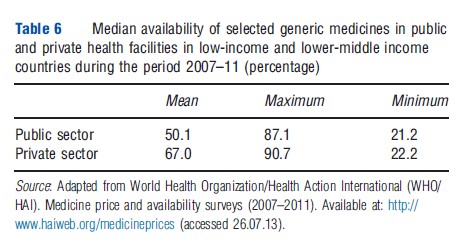

Fragmentation and opacity of information as a result of fragmentation across groups may cause poor coordination in distribution of medicines. Poor coordination impacts availability of health products as stock information may be poorly communicated; however, this may be less of a concern in the private sector, than in the public sector, as business profits may provide a greater incentive for better reporting in the private sector. In addition to availability, poor coordination may also impact the ability to track suboptimal and poor quality products entering the private sector medicines market (Table 6).

Public Sector Distribution

In most public sector distribution systems, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa, a centrally located warehousing and distribution point, often called a central medical store (CMS) manages the top tier of distribution. CMS then distributes medicines to regional or district stores depending on the geographic characteristics (i.e., the size of the country and relative distribution network) and product or programspecific supply systems. Often donor funding for specific products and/or health programs creates multiple vertical supply systems in the public sector.

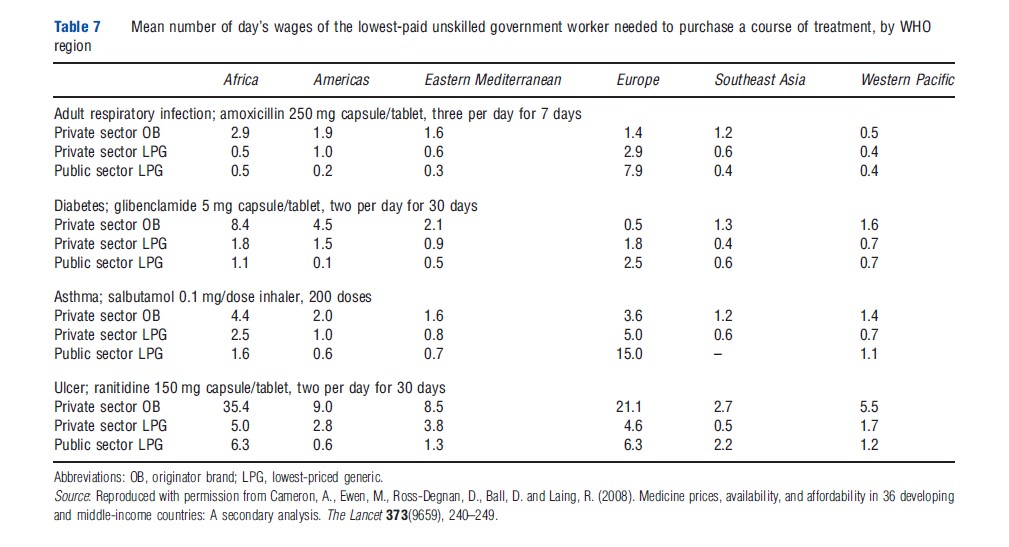

In many public sector supply systems, the risk of stockout at the health clinics is high because of skeletal distribution and reporting systems. As is such, availability tends to be lower in the public sector when compared to the private sector (see Table 5). In some cases, where pharmaceuticals are not free, increasing the prices of certain medicines covers distribution costs. This approach may lead to disparate access to certain medicines for which there are no vertical funding systems. In general, medicines provided in the public sector are more affordable to patients when compared with prices to mean number of day’s wages in the private sector (Table 7).

Nongovernmental Organization/Faith-Based Organization Distribution

NGOs and FBOs may also play an important role in distribution of pharmaceuticals in emerging markets. Distribution managed by NGOs and FBOs is often context specific, however, typically arranged according to a customer’s own prearrangement, courier services, drug supply organization delivery services, or direct delivery services. Medicines are often purchased according to customer inventory needs (pull system) or given through prepacked kits of essential medicines (push system). The level of involvement of NGOs/FBOs sector varies considerably across countries.

Summary

Pharmaceuticals play an integral role in the prevention and treatment of a variety of health conditions. Consistent access to pharmaceuticals remains a challenge in many national health systems. This is despite increasing levels of healthcare investment through domestic expenditures and large increases in DAH for low-income countries. This article reviewed the attributes of pharmaceutical sectors within low and lower-middle-income country health systems. Such analysis is important to ensure the long-term sustainability of national health systems and also to ensure that DAH investments have the intended impact of improving access to medicines.

An optimally designed health system will operate at a high level of technical and allocative efficiency. In this form, pharmaceuticals may be purchased and distributed at the lowest cost possible and the most appropriate set of pharmaceuticals will be provided to serve the needs of each specific population. To achieve these goals, elements of financing, procurement, distribution, and provision of pharmaceuticals must be effectively aligned.

For pharmaceuticals functions of collecting funds, pooling funds and spreading risks across groups, and allocating resources to purchase products often occur through a hybrid of multiple financing strategies. The most common forms of financing include OOP payments, private prepaid funds, RDFs, private healthcare insurance, CBHI, SHI, and government taxation.

With financing secured, pharmaceuticals must be purchased at prices to ensure affordability and long-term sustainability of the manufacturers. When thinking about different procurement structures it is important to consider the influence of different stakeholders in decision making. In decentralized models, purchasing power is distributed to a larger number of individuals within the health system. Decentralized procurement may provide individuals with more autonomy and flexibility, in turn lowering the number of stock outs. Conversely, decentralized procurement may also disempower smaller groups when negotiating lower prices with national or global suppliers. In nationally centralized systems the administrative and management costs required to ensure information is collected and pooled in a timely fashion may be challenging and complex. However, if done well, centralized systems with single payers, do improve the negotiating power of the payer as compared to the supplier. The tradeoff between flexibility with decentralized purchasing and lower prices with centralized purchasing should be assessed according to each context. Beyond national pooling, international pooled procurement arrangements are often used to facilitate pharmaceutical purchasing in low- and lower-middle income countries.

During purchasing and once pharmaceuticals have arrived in country, payers and governments use different levers to manage the prices of medicines. Price controls utilized include creating a comparison pricing standard, regulating wholesale and retail margins on pharmaceuticals, directive formularies as a part of health plans and health technology assessments. Outcomes-based pricing and risk-sharing arrangements are also gaining popularity in countries such as the UK especially for expensive chronic care medicines.

Another option often considered by countries to reduce medicine costs is to develop a domestic market for pharmaceutical production. Domestic production is thought to increase access to medicines through the reduction of production and shipping lead times, decline in importation costs and the development of local economy. Although it is reasonable to expect countries to seek self-sufficiency, not every context can support a domestic pharmaceutical industry. The decision to pursue domestic production versus importation of medicines is largely dependent on quality costs, regulatory costs, the size of the local market, competitiveness within the local market, and the economic status of the country.

Once a source is identified and medicines have been purchased, distribution is the final step required to ensure access. Pharmaceutical distribution often takes place through a combination of public sector, private sector, and NGOs/FBOs. Fragmentation within each of these sectors and across sectors often equates to poor information flows and opacity in the distribution chain. Improvements and investment in national healthcare distribution systems may facilitate more consistent availability and affordability of pharmaceuticals.

References:

- Batson, A., Evans, P. and Milstein, J. B. (1994). The crisis in vaccine supply: A framework for action. Vaccine 12, 963–965.

- Cameron, A., Ewen, M., Ross-Degnan, D., et al. (2009). Medicines prices, availability, and affordability in 36 developing and middle-income countries: A secondary analysis. Lancet 373(9659), 240–249.

- Carrin, G. (ed.) (2011). Health financing in the developing world: Supporting countries’ search for viable systems. Brussels: University Press Antwerp.

- Ekman, B. (2004). Community-based health insurance in low-income countries: A systematic review of the evidence. Health Policy and Planning 19, 249–270.

- Gomez-Dante´s, O., Wirtz, V., Reich, M., Terrazas, P. and Ortiz, M. (2012). A new entity for the negotiation of public procurement prices for patented medicines in Mexico. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 90, 788–792.

- Kanavos, P., Das, P., Durairaj, V., Laing, R., Abegunde, D. O. (2010). Options for financing and optimizing medicines in resource-poor countries. World Health Report: Background Paper, p. 34. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Kaplan, W. and Laing, R. (2005). Local production of pharmaceuticals: Industrial policy and access to medicines. Health, nutrition and population discussion paper. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Lu, Y., Hernandez, P., Abegunde, D. and Edejer, T. (2011). The world medicines situation 2011: Medicine expenditures. Geneva: WHO.

- Pauly, M. V., Zweifel, P., Scheffler, R. M., Preker, A. S. and Bassett, M. (2006). Private health insurance in developing countries. Health Affairs 25(2), 369–379.

- Ranson, M. K., Sinha, T., Chatterjee, M., et al. (2005). Making health insurance work for the poor: Learning from the Self-Employed Women’s Association’s (SEWA) community-based health insurance scheme in India. Social Science and Medicine 62(3), 702–720.

- Roberts, M., Hsiao, W., Berman, P. and Reich, M. (2008). Getting health reform right: A guide to improving performance and equity. New York: Oxford University Press.

- World Health Organization (2005). Social health insurance: Sustainable health financing, universal coverage and social health insurance. Fifty-Eighth World Health Assembly: Provisional Agenda Item 13.16. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Yadav, P., Smith, R. and Hanson, K. (2012). Pharmaceuticals in the health sector. In Smith, R. and Hanson, K. (eds.) Health systems in low- and middle-income countries: An economic and policy perspective, pp. 147–168. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Yadav, P., Tata, H. and Babaley, M. (2012). The World Medicines Situation 2011: Storage and supply chain management. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.