Health status improvements over the past 400 years have been steady, with a surge over the last century that is nothing short of spectacular, and a period during which economic progress has soared. Vaccines, antibiotics, and other medical advances have contributed to reductions in illness (morbidity) and mortality. Economic growth has shown equally impressive gains catapulting much of the world into higher income status with all of the associated consumption and health benefits that higher incomes allow. Richer people are better educated and nourished, and can afford investments that improve population health (3.9 Cutler and Lleras-Muney).

With economic advances and health status moving in tandem, the question is: Do health improvements spur growth, or do income increases determine progress in population health, or both? The evidence is mixed and hampered both by the lack of an acceptable and universal measure of health status and by the empirical difficulties inherent in controlling for reverse causality as well as nonlinearities.

Measurement of both growth and health pose challenges for both empirical estimation and for policy implications. For growth, the measurement is either of a static level of income, itself difficult to measure, or the dynamic of economic growth. Both may drive improvements in health, or serve as proxies for other achievements of higher-income countries such as education, effective public health interventions, or strong institutions, all of which correlate with improved health status.

The existing health metrics are inadequate to the task of effectively measuring the links between growth and health. No single measure exists to capture mortality and morbidity. Mortality only occurs once and is therefore a rare event. Common reliance on infant mortality reflects the high concentrations of deaths in the first year of life, and the availability of accessible and comparable data across countries. As infant mortality effectively captures differences across population health it is the measure of choice (1.1 Murray). Life expectancy serves a similar purpose but fails to capture health status as effectively, relegating its use to comparing broad national trends. More recent measures include life satisfaction and emotional well-being, malnutrition, and stunting (a measure of long-term malnutrition).

Accumulated evidence on the relationship between health and growth indicates that both directions of causality are plausible but neither is definitive. Existing evidence from cross-country macroeconomic studies analyze country-level relationships. More heterogeneous, microeconomic investigations provide analytic underpinnings for interpreting the findings of macroeconomic empirics and offer insights into some of the causal pathways of the relationships between health and growth and growth and health. These are discussed here.

How Have We Become So Healthy?

Mankind has become increasingly healthier over the past four centuries, and significantly so since 1900. Life expectancy at birth in the USA rose from 46 years and 48 years for men and women, respectively, in 1900, to 75 years and 81 years in 2010; a shift mirrored elsewhere in the industrialized countries, and observed in many developing countries as well. The major factors driving progress include improved nutrition, rising education, and advances in public health (1.7 Sahn). In contrast, health care investments have had far more modest effects on population health.

On the basis of his Nobel winning historical research on food production, malnutrition, and productivity Fogel (2004) estimates that improvements in the quantity and quality of food contributed to 40% of observed mortality declines since 1700, much of it during the twentieth century. Better nutrition raised agricultural output stemming famines and undernutrition. Parallel public health investments combined to steadily raise health status. Together labor productivity rose spurring economic growth.

Hygiene has also played a major role. In examining the explanation for mortality declines in England and Wales during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries historical research finds that immunizations, expanded access to piped water and sanitation, separation of water and sewerage, and better nutrition enhanced citizens’ abilities to ward off infections, thereby reducing morbidity and mortality levels. Scientific knowledge of disease transmission contributed importantly to public health, and led to reductions in transmission of water and foodborne diseases that further improved health status (4.1 Cookson and Suhrcke, 4.3 Mills). Again, the evidence shows no measurable effect of medical interventions on survival.

Over the centuries both health and economic growth have improved. The question is the possible causal relationship between them to inform policy on raising both health status and incomes. One important conclusion is that health investments have valuable social and household benefits; whether these benefits translate into faster economic growth is simply a search for further benefits.

Correlates Of Population Health And Income

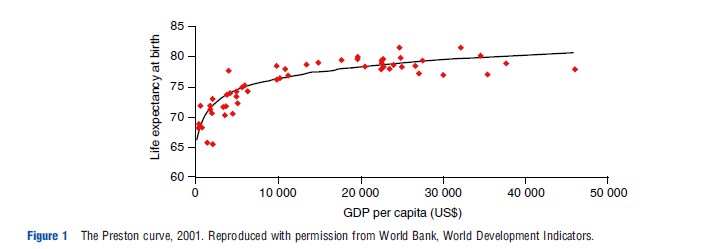

The first empirical estimation of the relationship of income and health status was offered by Preston (1975) using life expectancy as a proxy for health status. More recent data confirm his finding of a concave relationship between gross domestic product (GDP) and life expectancy (Figure 1) and show the same relationship as his original results, with the relationship becoming stronger over time as poor countries catch up to the wealthier world in life expectancy.

For the lowest income countries, small shifts in income lead to disproportionately higher life expectancies, often reflecting the first moves toward the demographic transition, as well as progress in public health. Preston attributed declines in mortality less to income and more to public health interventions and has suggested the combined importance of adequate calories, income, and education, echoing Fogel and others’ historical conclusions.

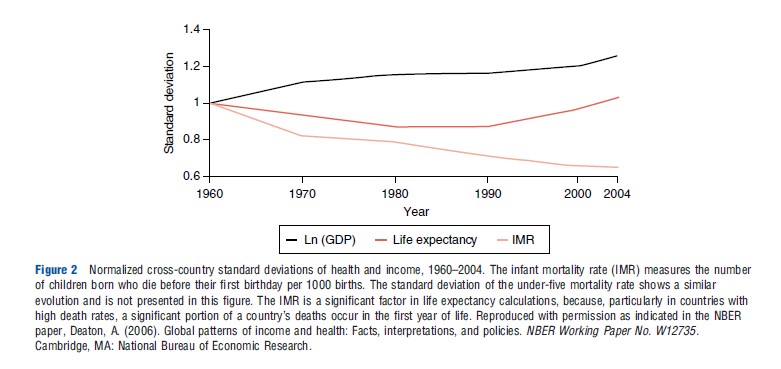

Extending Preston’s cross-sectional evidence with longitudinal data Deaton (2006) shows divergence among GDP, life expectancy, and infant mortality suggesting that the relationship between growth and health does not hold within countries over time. Each of the curves in Figure 2 is the standard deviation of the variable relative to its value in 1960. Thus, although country-level health indicators have converged per capita incomes have progressively diverged. If that is indeed the case then changes in income appear to be unrelated to health status measures.

Other researchers have argued for a strong and consistent relationship between growth in per capita incomes and reductions in infant and child mortality, and life expectancy based on cross-country, time-series data, and they point to poor economic performance as a cause of child mortality. They conclude that causality moves from income to health. Research examining the impact of income on emotional wellbeing in the US drawing on the Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Index shows that emotional well-being rises with log income but only to an annual income of US$75 000 after which there is no association. So income buys increasing well-being but at the lower end of the income scale.

Macroeconomic studies under the World Health Organization’s (WHO) 2001 Commission on Macroeconomics and Health initiative produced evidence of the link between health and economic growth concluding that health investments will make countries richer. The evidence affirms correlations, but causality remains elusive due to the inability to adjust for reverse causality, and the problem of omitted variables. There are a number of variables that affect both health and growth such as climate and disease prevalence complicating efforts to measure the effects of one on the other.

Subsequent research on the relationship between health and changes in income explore the dynamics of health and income shifts. In a highly controversial study geography is used as an instrumental variable for health status to address the endogeneity problem. The study finds a high correlation between population health and economic growth. Subsequent research reviewed 13 studies of cross-country regressions and all repeat the same strong results. Considerable debate and challenge has ensued on the appropriateness of geography (distance from the equator) and its importance to growth. Subsequent empirical studies from multiple researchers show that once the effect of geography on a country’s choice of institutions is controlled for, geography has little independent effect on growth.

Creative efforts were made to address the endogeneity problem including examination of twentieth-century breakthroughs in science such as drug therapies and insecticides and new global institutions such as WHO, but none find any independent effect on income growth though these new interventions did contribute to increases in population. Recent efforts to include microeconomic measures on the impact of health on productivity in a macroeconomic accounting framework find some modest gains in GDP. Incorporating general equilibrium effects to account for the diminished returns to labor with rapidly rising population have little effect as improvements in life expectancy do not lead to increases in per capita income or worker productivity.

Thus, despite creative approaches the controversy on whether health spurs growth remains a conundrum.

Individual Health And Productivity

Examining the same sets of relationships between income and health at the household level allows insights into how the factors interrelate to produce better health or higher incomes, and results in more robust findings. The downside of microeconomic studies is their limited generalizability, given the importance of different contexts in explaining effectiveness of interventions.

Morbidity And Income

Illness undermines productivity, in patterns similar to those Fogel identified between malnutrition and productivity. This cost-of-illness approach examines the short and longer term impacts of illness on education, labor productivity, employment, and economic activity.

A study of hookworm eradication in the American South tracking the impact of local infection control on education enrollment, attendance, and literacy suggests the importance of vector control in both education and incomes over lifetimes. The phasing in of hookworm control allowed an assessment of the patterns and extent of responses to eradication. Areas with higher pre existing infection rates saw bigger improvements after eradication. A parallel set of studies for malaria in the US c. 1930 and in Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico in the 1950s traced the effects of eliminating childhood exposure to malaria on adult literacy and earnings. The study concludes that ‘‘persistent childhood malaria infection reduces adult income by 40 to 60 percent.’’ Similar but less dramatic effects emerged from malaria eradication across Indian states in the 1950s, where literacy and primary completion rates rose by 10% in malaria-free areas (1.12 Cohen).

More recent experiments suggest the potential value of targeted treatment measures on schooling and earnings. In a study of randomly assigned deworming treatment for school children in western Kenya a 25% increase in student attendance was found among those receiving medication, although there was no effect on school performance, possibly due to the lack of any change in other inputs at the school.

Expanded access to antiretroviral treatment in many countries of sub-Saharan Africa has offered a laboratory to test the impact of interventions. In western Kenya those under treatment are 20% more likely to join the labor market and increase their weekly hours worked by 35%. In another study in the tea-growing region of western Kenya human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive tea pickers with 6 months on antiretroviral treatment increased their number of days worked and therefore their wages. Wage earnings rose from 75% to 89% of the wages of non-HIV-positive workers, thereby almost regaining the lost earning levels.

The impact of potential and actual parental death from HIV has shown some unexpected effects. In areas of high HIV prevalence across southern Africa children are less likely to go to school, take longer to go through school, and are less likely to graduate from primary school. More than half of the explanation is attributed to the expectations of a shorter life of parents, which will affect life chances of children rendering schooling of marginal benefit to future income. This complements evidence on the life chances of orphans emanating from an analysis of 10 Demographic and Health Surveys. Orphans in sub-Saharan Africa are significantly less likely to be in school as compared with their peers. Similar results emerge for Indonesia. However, country-level evidence is inconsistent in Africa. In Tanzania no impacts on schooling of HIV deaths of parents were found, perhaps because extended family members take on parenting roles for orphans (1.13 de Walque; 1.27 Thirumurthy).

A related and dramatic achievement in reducing the cost-of-illness is the multidonor program in the Niger Delta in West Africa where since the late 1990s pesticide spraying has controlled the black flies that had rendered the area uninhabitable. A total of 25 million hectares of rich agricultural land has been recultivated in reclaimed areas demonstrating yet again the value of public health interventions (1.16 Gre´ pin).

All of these studies document augmented productivity and impacts on education or output from improvements in health status, or measure the costs of poor health on these same indicators. Interventions at the household level as well as targeted regional investments in public health activities can have important effects on education and productivity (3.9 Cutler and Lleres-Muney).

Limited evidence exists on the link between income and health. Analysis of a unique data set for South Africa permits quantification of the impact of old-age pensions in South Africa on health status. Where households pool income, including pensions, the overall health status of the household improves through positive effects on nutrition, living conditions, and stress levels of adults. Surveys typically fail to capture income pooling, and this study allows good insights into how pooled incomes can influence investments that enhance health status.

Investing In Early Childhood Development And Adult Performance

Targeted investments and the impact on economic well-being have received increasing attention with particular focus on children. Mounting multisectoral evidence from economics, psychology, and neuroscience makes the case that investments in disadvantaged young children have profound effects on learning, earnings, and adult health. Recent overviews point to factors such as maternal undernutrition, poverty, poor health, and unstimulating home environments as strongly associated with adult cancer incidence, mental illness, lower incomes, and lower birthweight of offspring. A review of microeconomic studies concludes that nutrition and possibly other dimensions of health compromise productivity. Heckman (2007) emphasizes the economic importance of noncognitive skills and their importance in future economic and social behavior, which in turn influence productivity and earnings. The US research suggests that the economic rate of return to preschool attendance among disadvantaged children dwarfs returns to other, later academic investments (3.1 Royer and Bauer; 4.13 Karoly).

Longitudinal studies provide strong evidence of the value of early childhood interventions. Low birth-weight negatively affects long-run adult outcomes such as height, intelligence quotient (IQ), educational attainment, and earnings. Bolstering early nutrition interventions translate into greater cognitive development, physical stature and strength, greater learning, higher adult productivity, and healthier offspring. A 35-year longitudinal study in Guatemala traced adult participants who had received a randomly distributed nutrition supplements as school children. Women had 1.17 more years of schooling, their children were 179 g heavier at birth, and their children were 30% taller as adults compared with the children of those who had not received the supplement. Men in the treatment group earned an average wage of 46% above those who only received the calorie-based supplement (1.3 Soares; 1.7 Sahn).

Consistent, robust evidence on returns to early childhood investments confirms the importance of targeted interventions for disadvantaged children. Although often difficult because many young children remain at home, targeted early childhood programs have a clear payoff in higher productivity and earnings over a lifetime and better health in adulthood. They also offer the possibility of breaking the intergenerational cycle of poverty.

Health-Related Interventions And Health: Implications For Policy

If economic progress simply solved the problems of mortality and morbidity, then public policy would no longer be concerned with public health and health care needs would be met. Similarly, if investments in health provided the needed impetus for growth resource allocation decisions would be straightforward. However, circumstances are more complex and targeted policy decisions influence economic growth and population health.

Part of the interest in the growth to health link is to determine whether economic progress means more investments in health. A panel study of all countries in the 2010 WHO database examines the elasticity of public health spending with respect to national income controlling for demographics, source of financing, and other characteristics. A dynamic model using a lagged dependent variable adjusted for endogeneity shows results consistent with earlier studies in that GDP and public health expenditures move in tandem, but contrary to other studies finds significant elasticities below 1.0 for all but the lowest income countries, and lower values for the dynamic model results. So under this specification, income growth does not translate into commensurate increases in health spending.

If greater health investments could assure both better health status and rapid economic growth, then spending on health would need to be a priority given the large social and economic benefits. However, ample evidence suggests that spending alone falls short of even achieving health goals. The link from health spending to health outcomes is weak, and cross-country evidence shows minimal correlation between spending and health outcomes. As global access to important preventive and treatment technologies does not differ dramatically and funding is on the rise, it suggests that institutions and other factors such as education underpin the divergence between spending and outcomes. Chronic absenteeism, inadequate budget execution, illegal payments, and poor management combined with a severe lack of accountability translate into absence of the very technologies that can save lives at the point of service, such as drugs, supplies, and equipment, which in turn means low returns on investment. Poor governance in service delivery suggests government failure, effectively government interventions that have gone wrong. Without sound institutions, public health investments will not improve health, let alone economic growth (1.22 Government Regulation and Corruption – no author).

So despite advances in technology, countries experience marginal gains where countries lack institutions that can ensure effective delivery and financing of health care services. However, the discrepancy extends to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, where studies of survival rates for specific diseases do not correlate with either total or public spending.

Debate on the path to better health and economic growth will continue given the inconclusive nature of the evidence. Better research and measurement will help to hone the findings and provide stronger policy guidance; but stronger institutions to ensure effective health care delivery will require equal attention.

References:

- Deaton, A. (2006). Global patterns of income and health: Facts, interpretations, and policies. NBER Working Paper No. W12735. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Fogel, R. (2004). The escape from hunger and premature death, 1700–2100: Europe, America and the Third World. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Heckman, J. (2007). Investing in disadvantaged young children is good economics and good public policy. Testimony before the Joint Economic Committee, Washington, DC, June 27.

- Preston, S. H. (1975). The changing relation between mortality and level of economic development. Population Studies 29(2), 231–248.

- Bleakley, H. (2007). Disease and development: Evidence from hookworm eradication in the American South. Quarterly Journal of Economics 122(1), 73–117.

- Bloom, D., Canning, D. and Sevilla, J. (2004). The effect of health on economic growth: A production function approach. World Development XXXII, 1–13.

- Commission on Macroeconomics and Health (2001). Macroeconomics and health: Investing in health for economic development. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Cutler, D. and Miller, G. (2005). The role of public health improvements in health advances: The twentieth century United States. Demography 42(1), 1–22.

- Grantham-McGregor, M., et al. (2007). Development potential in the first 5 years for children in developing countries. Lancet 369, 60–70.

- Jack, W. and Lewis, M. (2009). Health investments and economic growth: Macroeconomic evidence and microeconomic foundations. In Spence, M. and Lewis, M. (eds.) Health and growth, pp. 1–39. Washington, DC: Growth Commission.

- Lopez-Casasnovas, G., Rivera, G. B. and Currais, L. (eds.) (2005). Health and economic growth: Findings and policy implications. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Spence, M. and Lewis, M. (eds.) (2009). Health and growth. Washington, DC: Growth Commission.