Public goods have, for centuries, been part of the economic analysis of government policy at the national level. This has included many goods associated with improving population health, such as water and sanitation. However, in an increasingly globalized world, health is an ever more international phenomenon. Each country’s health affects, and is affected by, events and processes outside its own borders. The most obvious example of this is in communicable disease, where an outbreak such as sudden acute respirator syndrome (SARS) or pandemic influenza in one country very rapidly spreads and affects many others.

It is becoming clear in many areas that matters which were once confined to national policy are now issues of global impact and concern. This has been evidenced, for example, in dealing with environmental problems such as carbon emissions and global warming. These not only affect the nation involved in their production but also impact significantly on other nations; yet no one nation necessarily has the ability, or the incentive, to address the problem. Similarly, health improvement requires collective as well as individual action on an international as well as national level. Initiatives such as the Global Fund to Fight human immuno-deficiency virus (HIV)/ aquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), Tuberculosis, and Malaria reflect a growing awareness of this. However, initiating, organizing, and financing collective actions for health at the global level presents a challenge to existing international organizations. Recognition of this led initially to the development of the concept of Global Public Goods, and more recently the consideration of Global Public Goods for Health, as a framework for considering these issues of collective action at the international level.

What Are Global Public Goods?

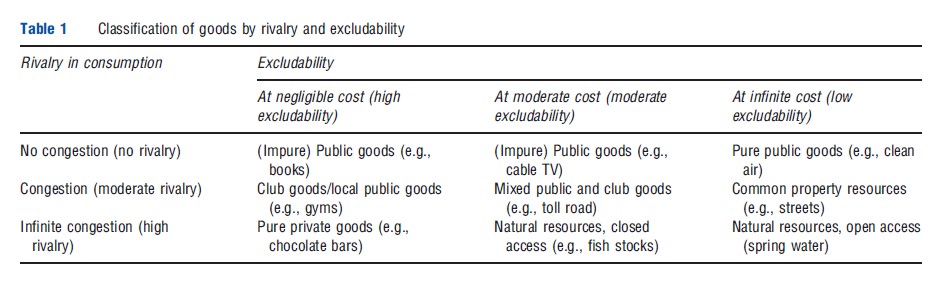

The global public goods concept is an extension of the economic tradition of classifying goods and services according to where they stand along two axes – one measuring rivalry in consumption, the other measuring excludability – as illustrated in Table 1.

Pure private goods are those that are most used to dealing within day-to-day lives, and are defined as those goods (like a loaf of bread) that are diminished by use, and thus rival in consumption, and where individuals may be excluded from consuming them. At the opposite end of the spectrum are pure public goods, which are nonrival (not diminished by use) and nonexcludable (if the good is produced, it is freely available to all). For example, broadcast radio is nonrival (many can listen to it without preventing others from listening to it) and nonexcludable (it is difficult to exclude someone from receiving it). In between these extremes are ‘impure’ goods, such as ‘club goods,’ which have low rivalry but high excludability, and ‘common pool goods,’ which have low excludability but high rivalry. In these cases, exclusion may occur through geographic, monetary, or administrative prohibition, and some goods are rival relative to capacity (e.g., a sewage system with spare capacity is nonrival, but once at capacity, its use becomes rival).

One of the fundamentals of public economics is that the free market – the interplay of individual supply and demand decisions mediated through the price system – will result in the provision of less than the collectively optimal level of public goods. Thus, the nation state has a role to play either in producing the good directly (the traditional approach) or at least in arranging for its production by a private firm (the increasingly popular ‘outsourcing’ strategy).

Note that, importantly, a good need not be a pure public good to suffer from a collective action problem. Collective action problems also apply to private goods which have substantial positive externalities, as these too will be undersupplied (because externalities are not taken into account by private suppliers and consumers). For example, an individual secures only part of the benefit from his/her treatment for tuberculosis, as others benefit from the reduced risk of infection. However, it is only this private benefit that the individual will take into account when considering whether to seek treatment. Where the private benefit is less than the cost to the individual, they will not seek treatment, even though the population as a whole (including the individual sufferer) would be better off if the individual received treatment.

Table 1 Classification of goods by rivalry and excludability

Thus, from a policy perspective it makes little sense to draw too categorical a distinction between private goods with large positive externalities and the pure public good case. In a sense, an intervention that would counter a nonpublic good-related collective action problem, so as to correct the under or oversupply of positive or negative externalities, widely spread among the population, can itself be considered a public good. For example, providing infrastructure capable of delivering timely and effective treatment for tuberculosis, and the policies to provide an incentive for individuals to seek and complete treatment, may have the characteristics of public goods, even though the treatment of an individual is essentially a private good with positive externalities.

Turning to the global level, a reasonable functional definition of global public goods would be public goods that occur across a number of national boundaries, such that it is rational, from the perspective of a group of nations collectively, to produce for universal consumption, and for which it is irrational to exclude an individual nation from consuming, irrespective of whether that nation contributes to its financing. The key issue facing provision of these goods is how to ensure collective action in the absence of a ‘global government’ to directly finance and/or provide the public good.

For an interesting panel discussion of global public goods more generally, which includes the 2001 Nobel Prize winner for economics Joseph Stiglitz, http://www.youtube.com/ watchv=2hmMWADaPJA

How Do Global Public Goods Relate To Health?

As should be apparent from Table 1, ‘health’ itself is a private good, as are the majority of goods and services used to produce health. One person’s (or one country’s) health status is a private good in the sense that he/she (or it) is the primary beneficiary of it. To illustrate this, consider the parallel of a garden: if someone cultivates an attractive garden in front of his/her house, passersby will benefit from seeing it; but it remains a private good, the main beneficiary of which is the owner, who sees more of it and is able to spend time in it. An individual’s health remains primarily of benefit to that individual, although there may be some (positive or negative) externalities resulting from it; typically exposure to communicable disease.

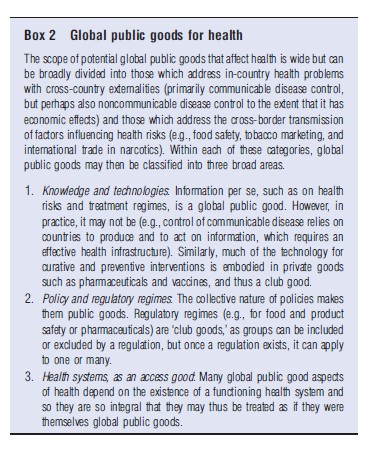

Further, in terms of the goods and services which are necessary to provide and sustain health, such as food, shelter, and use of curative health services, ‘health’ is often rival and excludable between individuals and nations. Nonetheless, there are two important externality aspects of health, both at the local level and across national borders, which may be amenable to conceptualizing as having global public good (GPG) properties: (1) prevention or containment of communicable disease and (2) wider economic externality effects (Box 1). However, there are several global public goods for health which are public goods yielding improvements in health globally. These include aspects of knowledge (and technology) production and dissemination, policy and regulatory regimes, and health systems (Box 2).

The last of these may not be immediately apparent, as it is not a public good but what is termed an access good. These are private goods that are required such that a public good may be accessed. For instance, taking the example of broadcast radio earlier, to obtain this public good one requires a radio (which is excludable and rival) to access it. Thus, in many cases, public goods, such as disease eradication, require a minimum health system (e.g., access to vaccinations) to enable access to them (or, alternatively, to allow production of them). Such private goods may often be considered as if they were public goods to the extent that their provision is a vital element of provision of the public good itself.

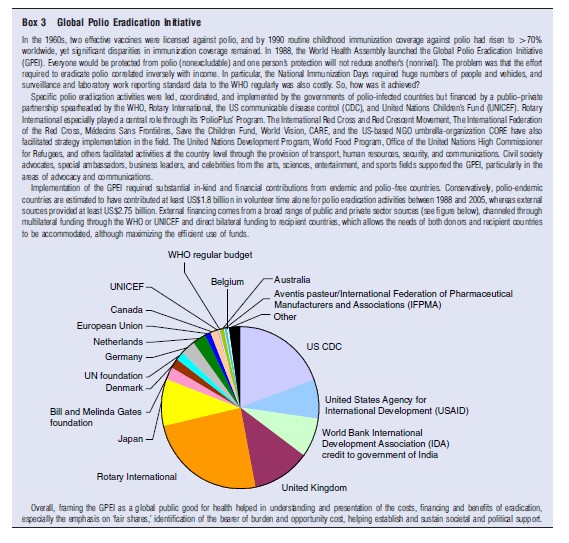

Production And Finance

Clearly, global public goods need to be produced and financed, and the precise details of each of these will vary according to the specific issue at hand. For instance, production of disease eradication will require production to be locally based in the distribution and administration of vaccines, but may be financed through a variety of organizations and with different mechanisms, from local health services to Non-Governmental Organization (NGOs) to private companies, through gifting of vaccines, provision of local health service personnel, and international surveillance. In this respect, the example of polio eradication is provided in Box 3.

The core issue in provision and finance is that national public goods are dealt with by government intervention, through direct provision, taxes, subsidies, or regulation, but in the case of global public goods, the absence of a ‘global government’ means that the collective action problem becomes more complex with the increased number of players involved and the need for effective incentives for compliance. The main potential contributors to provision and/or finance are: (1) national governments; (2) international agencies (including philanthropic foundations and NGOs); and (3) commercial companies. However, these players’ agendas (their preferences or priorities) do not necessarily coincide with each other. The more divergent these agendas are, the lower the chance of the good being produced. Impediments to international cooperation, and the role of international bodies in facilitating it, are, therefore, central to consideration of the provision and financing of GPG.

A significant constraint in global collective action is the ability of countries to pay according to the proportion of the benefits they receive from the good in question, as this undermines the political will to cooperate and limits effective participation. Even the creation of a legal duty does not ensure compliance, as this depends on having adequate resources to fulfill such obligations. Further, where countries with inadequate resources do participate in global programs, financial and human resources may be diverted from other essential activities, with possible adverse effects on health. The opportunity cost of these resources is far greater in developing than developed countries, creating tensions in securing global cooperation and reducing the net health benefits. Circumventing this problem requires that financial and other contributions reflect each country’s ability to contribute, as well as its potential benefits. In practice, this means that financing needs to come predominantly from the developed world. However, it is important here to understand that this does not imply the use of overseas development assistance. Global public goods are not substitutes for aid but a complement to it: presenting an added rationale for international cooperation and assistance. Developed countries benefit from global public goods; yet because their provision is rooted in the national level, it is, therefore, in the self-interest of wealthy nations to assist poorer nations in contributing to the production of such goods. Thus, investment in poor countries is encouraged, not because they are poor per se, but to enable them to make their contribution to goods essential to developed countries.

The provision of global public goods depends on the ability to create arrangements that account for differing incentives and means of developed and developing countries. Thus, where developed countries have the incentives to produce the good and developing countries do not, but where the participation of the developing country is vital, developed countries will be required to fund the costs to developing countries of participating in production of the good. In contrast, when incentives exist for developing countries, but not for developed countries (where diseases are disproportionately incident in poor countries), developed countries might assist in providing incentives for the commercial sector (‘push and pull’ mechanisms such as subsidization for research, advance purchase commitments, and expansion of orphan drug laws) or facilitate market access. This brings us on to mechanisms for financing global public goods.

The provision of global public goods depends on the ability to create arrangements that account for differing incentives and means of developed and developing countries. Thus, where developed countries have the incentives to produce the good and developing countries do not, but where the participation of the developing country is vital, developed countries will be required to fund the costs to developing countries of participating in production of the good. In contrast, when incentives exist for developing countries, but not for developed countries (where diseases are disproportionately incident in poor countries), developed countries might assist in providing incentives for the commercial sector (‘push and pull’ mechanisms such as subsidization for research, advance purchase commitments, and expansion of orphan drug laws) or facilitate market access. This brings us on to mechanisms for financing global public goods.

Here, voluntary contributions are the most straightforward option but are particularly prone to the free-rider problem as each country has an incentive to minimize its contribution. More formal coordinated contributions, negotiated or determined by an agreed formula, are commonly used to fund most international organizations (e.g., the World Health Organization (WHO)). Although limiting the ‘free-rider’ problem, each country has an incentive to negotiate the lowest possible contribution for itself (or the formula that will produce this result). Rewarding contributions with influence, to avoid this problem, skews power toward the richest countries (e.g., the international monetary fund (IMF) and World Bank); but without such incentives (or effective sanctions), countries have little incentive to pay their contributions in full (e.g., the US contributions to the United Nations (UN)). Global taxes, although theoretically the most efficient means for financing global public goods, face substantial opposition, limiting the prospects of securing funding from this source for the foreseeable future. More ‘market’-based systems have been advocated, but as the USA’s withdrawal from the carbon-trading system proposed in the Kyoto Agreement demonstrates, without effective enforcement mechanisms, the free-rider problem remains. More recently, the constructive use of debt has been suggested, to allow the world to consume more goods that are global sooner and pay for them over a longer period. For certain diseases, the risks that they pose and the consequences of poverty that they perpetuate, debt (and hence loans) might make good sense. Buying time also allows the possibility that those countries not able today to help to pay for global public goods, borrow to do so in the future when their economies are more productive. The appropriateness of the precise mechanism chosen will depend on the specific good being considered.

Conclusion

The problem with public goods is that market mechanisms undersupply them. National governments usually provide finance and/or production. At a global level there is no world government. Thus global public goods require some means to ensure collective action to correct market failure at a global level. The advantage of the global public good concept in areas requiring global collective action is that it frames issues and objectives of policy – improving heath – in ways that make explicit the inputs needed (mix of public and private goods, domestic and international inputs, and incentives required) to produce and disseminate the final ‘good.’ Treating the final product as a ‘good’ in this way rather than a policy objective facilitates the analysis of who benefits and loses from its production, identifying (dis)incentives involved and thus facilitating the design of appropriate financing mechanisms.

The concept makes it clear that policy makers and their constituencies need to recognize interdependencies and the futility as well as the inefficiency of attempts to act unilaterally – porous borders have globalized health issues, and international cooperation in health has become a matter of self-interest.

References:

- Commission on Macroeconomics and Health (2001). Macroeconomics and health: Investing in health for economic development. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Kaul, I. and Concei-ca˜o, P. (2006). The new public finance: Responding to global challenges. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Kaul, I., Concei-ca˜o, P., Le Goulven, K. and Mendoza, R. (2003). Providing global public goods: Managing globalization. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Kaul, I., Grunberg, I. and Stern, M. A. (1999). Global public goods: International cooperation in the 21st century. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Sandler, T. (1997). Global challenges: An approach to environmental, political and economic problems, ch. 5. Cambridge, New York, and Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.

- Smith, R. D. (2003). Global public goods and health. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 81(7), 475 (editorial).

- Smith, R. D., Beaglehole, R., Woodward, D. and Drager, N. (2003). Global public goods for health: A health economic and public health perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Smith, R. D. and MacKellar, L. (2007). Global public goods and the global health agenda: Problems, priorities and potential. Globalization and Health 3, 9, https://globalizationandhealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1744-8603-3-9

- Smith, R. D., Thorsteinsdo´ttir, H., Daar, A., Gold, R. and Singer, P. (2004). Genomics knowledge and equity: A global public good’s perspective of the patent system. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 82(5), 385–389.

- Smith, R. D., Woodward, D., Acharya, A., Beaglehole, R. and Drager, N. (2004). Communicable disease control: A ‘Global Public Good’ perspective. Health Policy and Planning 19(5), 271–278.

- Tobin, J. (1978). A proposal for monetary reform. Eastern Economic Journal 4(3–4), 153–159.