By the end of 2009, the year in which Mexico first reported human infections with the H1N1 influenza A virus that then spread globally to cause a pandemic, 70 715 Mexicans had been reported with confirmed H1N1 infection of whom 1316 (~5%) had died. During this same period, though there were no official travel or trade bans from th,1e Mexican Government or international bodies such as the World Health Organization (WHO), Mexican tourism and trade in pork decreased both nationally and internationally. Temporal decreases in output from the pork industry contributed to a pork trade deficit of an estimated US$27 million, whereas an estimated loss of one million overseas visitors translated into an estimated economic loss of approximately US$2.8 billion.

The economic losses related to H1N1 outbreak in Mexico were clearly influenced by the unfounded perception by tourists and travel agencies that the risk of becoming infected with H1N1 was somehow greater in Mexico than elsewhere, even though the virus had spread throughout the world; and by a misunderstanding among pork trade partners that the pandemic was being amplified by infected pigs, despite the fact that it was human to human transmission, in which swine played no role, that was responsible for the global spread of the pandemic. In other countries, there were official recommendations, apparently based on this same misunderstanding that also caused negative economic impact. In Egypt, for example, slaughter of pigs was ordered by the Egyptian Government early in the pandemic, even though the H1N1 virus had already been demonstrated to be highly transmissible from human to human, and despite the recommendation of the World Health Organization for Animals that culling of pigs was not scientifically justifiable.

Countries around the world were affected as the H1N1 pandemic spread, and economies suffered. In Spain, for example, the direct economic impact of illness from H1N1 influenza on health services utilization, and indirect costs from work absenteeism, for example, has been estimated at €6236.00 per hospitalized patient. In Canada, it is estimated that the cost of the increased patient load to hospitals caused by H1N1 between April and December 2009 was Canadian $200 million.

The World Bank predicts that a pandemic caused by a different influenza virus, the highly infectious and virulent avian (H5N1) influenza virus, could cost the world economy as much as US$800 billion a year from direct patient costs, and indirect costs from lost lives, travel, and trade. The H5N1 virus is currently continuing to cause disease among poultry, but is only able to infect humans sporadically when they come in contact with infected chickens.

As influenza viruses are highly unstable, however, the H5N1 influenza virus could mutate or combine with other influenza viruses circulating in nature to a form that spreads easily from human to human, resulting in an influenza pandemic with much higher mortality than the H1N1 pandemic. To prevent such a scenario, attempts are being made to eliminate the H5N1 virus by culling entire flocks of infected poultry, mainly chickens. This precautionary measure, recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Food and Agriculture Organization, is causing lost revenue and poultry-replacement costs that have been estimated to be in billions of US dollars.

Emerging infections such as H1N1 and H5N1 influenza are the newly identified infectious diseases in humans caused by viruses that have breached the species barrier between an infected animal and a human. They are by definition new, and sometimes they are called novel infections. As they are new they are poorly understood, and their full potential to cause disease and death in humans is not known.

Unlike influenza, there are other emerging infections that cause human disease but are unable to spread from human to human. Economic cost associated with these infections is due to patient management and decreased work productivity while sick; and if there is death, from the lost years of work. An example is rabies: humans are infected by the bite of a rabies infected animal, become sick and die, but do not spread the infection to other humans unless an organ is obtained from them postmortem, and grafted into another human. The direct cost of treating persons exposed to rabies has been estimated (conservatively) to be US$40 in Sub-Saharan Africa and US$49 in Asia, a cost that equals 5.8% and 3.9%, respectively, of the average annual per capita gross national income. Additional indirect costs attributed to persons with rabies occur because of death and permanent removal from the workforce. It is estimated that the economic impact from rabies each year in the United States is approximately $300 million, where an average of two human infections occur each year.

Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) is another example of an emerging infection that does not spread from human to human. BSE, or mad cow disease, was identified in the United Kingdom (UK) during the 1980s. To rid cattle populations of infection, precautionary culling of herds with infected cattle was required. When it was understood that humans could be infected with BSE from cattle and cattle products in 1996, culling activity increased, and the economic loss in the UK during the following year was estimated to be US$1.5 billion. Countries that had imported cattle from the UK also culled infected herds at a considerable economic loss.

Another emerging infection – monkeypox virus in the United States – was caused by human contact with infected prairie dogs bought as pets. The prairie dogs had been infected with the monkeypox virus in pet shops by other animals imported from West Africa as exotic pets. The outbreak was stopped and there were no deaths. Though the overall direct costs for diagnosing and managing illness were not calculated, nor were the costs from the bans on pet sales by pet shops and their furnishers, they were significant to health insurance companies and to the trade in animals as pets.

Occasionally, an infection emerges at the human/animal interface, is able to spread easily from human to human, and then becomes endemic in human populations with long-term associated economic cost. HIV is one such emerging infection. Thought to have crossed the species barrier from nonhuman primates to humans sometime during the early twentieth century, it is spread from human to human mainly by intimate sexual contact. Owing to the long, symptom-free incubation period, HIV had already spread throughout the world’s population by the time it was first identified in 1981. Since then the cumulative economic impact of AIDS on GDP has been estimated by various economists with a wide range of costs – one of these, the estimated direct costs in 2009 to achieve universal access to treatment and care alone was US$7 billion.

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS): A Case Study On The Economic Cost Associated With Emerging Infectious Disease Outbreaks

An outbreak of an emerging infection, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome virus, occurred in the Guangdong Province of China in late 2002. In China, SARS spread from infected persons to other family members and to health workers, and from them to others in the community, causing an outbreak associated with severe illness and death. In February 2003, when SARS was still unrecognized as a new and emerging infection in China, it crossed the border from the Guangdong Province to Hong Kong in a doctor, who had been treating patients with SARS. He himself had become sick, and during a one-night stay in a Hong Kong hotel spread SARS to other hotel guests. Before they had any major symptoms, infected hotel guests travelled by plane to other Asian countries, North America, and Europe where they became sick and spread infection to others.

SARS had never before been seen in humans. There were thus no vaccines, medicines, or predetermined measures that could be used for its control. As the virus continued to spread from human to human, there was concern that like HIV, it would become yet another endemic infection, sustaining itself indefinitely in humans. Precautionary measures to prevent international spread of the infection were immediately recommended by the WHO – it was first recommended that persons who were ill with similar symptoms and contact with geographic areas where outbreaks were occurring defer their travel until they were well.

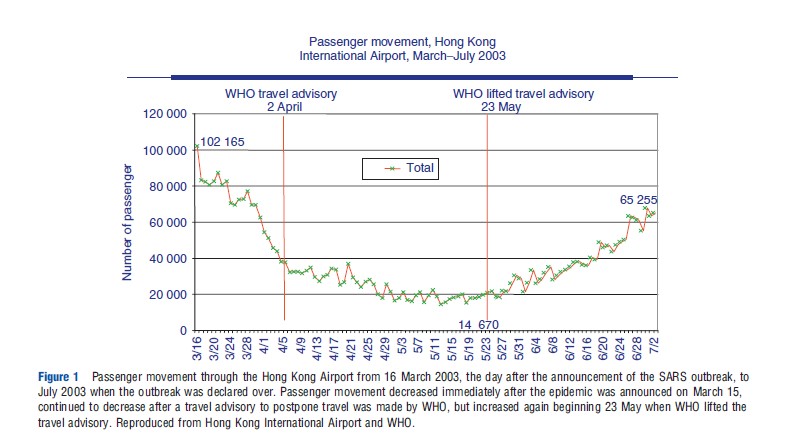

These precautionary measures caused a decrease in international air travel from geographic areas where outbreaks were occurring. Concern and panic ensued, however, among populations from other geographic areas as well – clearly demonstrated in a decrease in passenger movements through international airports. The precautionary prevention measures recommending that persons who were ill with SARS-like symptoms postpone travel resulted in a decrease of passengers who were ill, but many well passengers perceived the risk of travel as being great. This resulted in a steady decrease in passenger movement, clearly shown in Figure 1, where passenger movements at the Hong Kong International Airport decreased soon after the outbreak was announced.

When SARS spread throughout a major housing complex in Hong Kong, among persons who had not been in contact with each other it was hypothesized that SARS might be spreading through an environmental factor such as an insect or water in addition to face to face contact. This led to stronger precautionary recommendations – to postpone or cancel travel to areas where outbreaks of SARS were occurring and a human contact could not be identified as a source of infection for each person with SARS. When WHO made this stronger precautionary recommendation on 2 April, a sustained decrease in passenger movement occurred in Hong Kong throughout the month of April and until 23 May, when the WHO removed the precautionary travel advisory.

Overall, Hong Kong International Airport had had an approximate decrease of 70% in passenger movements in April 2003 compared with April 2002, and aircraft movements decreased by an estimated 30%. In April 2003, the number of flights cancelled each day was approximately 164, representing more than 30% of all flights cancelled, and resulting in an estimated loss in landing fees of a minimum of $3.5 million per day.

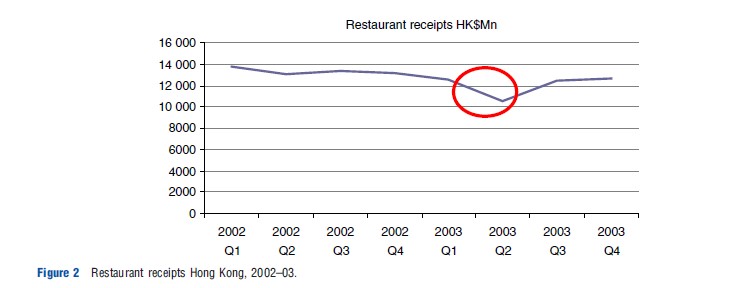

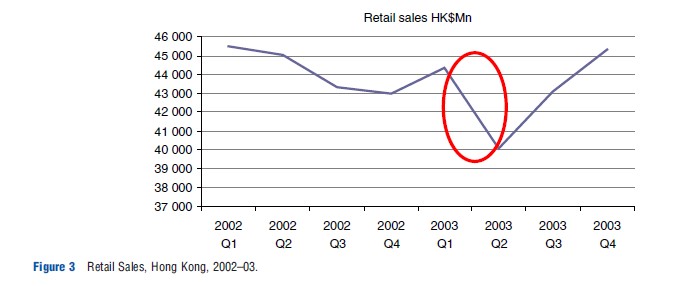

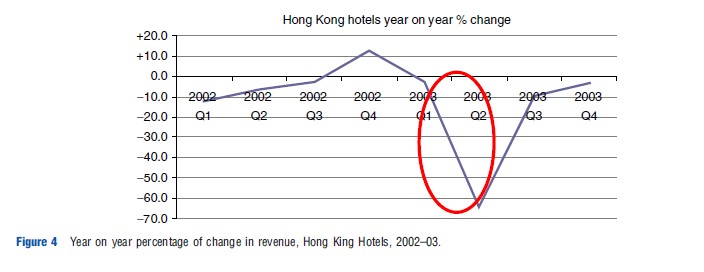

During this same period, income from restaurants, hotels, and retail sales decreased because of panic and misperception of the risk among the Hong Kong population that resulted in decreased consumer activity. Figures 2–4 provide clear examples of the decreases in economic activity that occurred.

The SARS outbreak caused ended in July 2003, with 8096 reported cases from 37 countries of which 1706 (21%) were fatal. The Asian Development Bank estimated the economic impact of SARS at approximately US$18 billion in East Asia – around 0.6% of gross domestic product. However, fortunately recovery was rapid once international spread had been stopped.

The International Health Regulations And International Spread Of Infectious Diseases

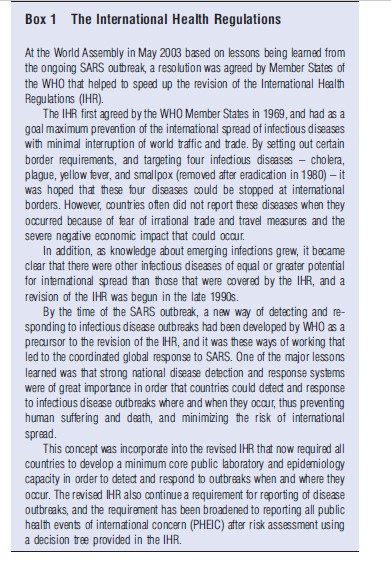

Attempts to limit the international spread of infectious diseases were first recorded in Venice in the fourteenth century when quarantine was used to keep ships and individuals at land border crossings in isolation for 40 days in an attempt to stop the spread of plague. Quarantine was widely used during the following centuries to attempt to limit the spread of plague and other diseases such as cholera, yellow fever, and smallpox; and during the nineteenth century a series of sanitary conferences within and between Europe and the Americas focused on these same four diseases demonstrated the concern. In the early twentieth century these sanitary conferences were broadened, under the League of Nations, to include all its member states. In 1969, the WHO Member States had agreed to a set of regulations aimed at ensuring the maximum security against the international spread of diseases with a minimum interference with world traffic.

The IHR 1969 were revised in 2005, incorporating many of the lessons learned during the SARS outbreak, and now ensure broader disease coverage, and in addition require countries to develop core capacities in public health laboratory and epidemiology in order to detect and respond to diseases where and when it occurs, and before it spreads internationally (Box 1).

Several disease threats have occurred since the revision of the IHR, including the H1N1 pandemic in 2009. The risk assessment when H1N1 first emerged was conducted by WHO and the IHR emergency committee. Though WHO recommendations based on this risk assessment clearly stated that travel and trade should continue as before, irrational trade and travel measures were imposed by several countries as described earlier in this article, and they resulted in the consequent economic losses described.

The outbreak of Escherichia coli (E. coli) that caused hemolytic-uremic syndrome in Germany occurred after the revision of the IHR as well. Though the outbreak resulted in an unexpected direct economic burden on the German health system, it also resulted in a severely negative economic impact on the European agricultural sector. Initial laboratory testing wrongly suggested that the outbreak was associated with consumption of salad greens and tomatoes imported from various countries neighboring Germany, and with consumption of cucumbers imported from Spain. Once this link was published in the mass media, the market for cucumbers fell and Spanish farmers began to experience losses of up to an estimated US$ 200 million per week. Polish, Dutch, and Italian farmers had similar losses, and German vegetable farmers had a drop in real income of 2.8%.

At the same time, Russia banned vegetable imports from the entire European Union (EU), an annual 600 million Euro market for EU farmers. As the outbreak investigation continued, however, it became clear that the outbreak was linked to ingestion of bean sprouts from an organic farm in Lower Saxony and the EU then compensated farmers in the European vegetable industry with 200 million Euros.

These two outbreaks suggest that the IHR 2005 are not completely effective in clear and effective risk communication, nor in preventing unnecessary negative economic impact. A recent outbreak of a novel coronavirus in the Middle East, however, gives cause for hope that the revised IHR do indeed offer a means of ensuring maximum security against the international spread of infectious diseases, while minimizing interference with travel and trade.

Reports of persons infected with this newly identified SARS-like virus were made to the WHO from countries treating patients with origins in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Jordan, and the United Arab Emirates. The initial reports originated at the time of religious pilgrimage for Hajj. An irrational response could have caused great confusion and a heavy economic and spiritual loss to pilgrims and to Saudi Arabia, which has increased its investment each year to provide for the health security of pilgrims.

An immediate and transparent risk assessment was made under the framework of the revised IHR, and the risk was then communicated widely. The Hajj was unaffected by the reports of the risk assessment, and surveillance of Hajj pilgrims for severe respiratory symptoms was conducted during the pilgrimage and after pilgrims had returned to their home country.

Only time will tell whether the new ways of working and communicating risk under the IHR will continue to help prevent unnecessary panic and confusion when an outbreak occurs and spreads internationally; and prevent the irrational reaction that increases their negative economic impact.

References:

- BBC. (2011a). E. coli cucumber scare: Spain angry at German claims. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-13605910.

- BBC (2011b). E. coli: Russia bans import of EU vegetables. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-13625271.

- Bloom, E., de Wit, V. and Carangal-San Jose, M. J. (2003). ERD Policy Brief No. 42 – Potential economic impact of an avian influenza pandemic in Asia. Asian Development Bank. Available at: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/28082/pb042.pdf.

- Heymann, D. L. and Rodier, G. (2004). SARS: A global response to an international threat. Brown Journal of World Affairs, Winter/Spring X(2), 185–197.

- Smith, R. D., and Sommers, T. (2003). Assessing the economic impact of public health emergencies in international concern: The case of SARS. Globalization, Trade and Heath Working Papers Series. Geneva: World Health Organization

- The World Bank. (2005). Avian flu: Economic losses could top US$800 billion. World Bank News and Broadcast. 8 November 2005..