Introduction

Importance Of The Theory

Why do consumers purchase health insurance? To purchase anything, the consumer must give up something, and in the case of health insurance, that ‘something’ is the premium payment. Although the nature of the premium payment is clear (to both consumers and economists), what is not clear is the nature of the benefits that consumers receive in return. This represents the central objective and the challenge of health insurance theory: to describe just what it is that consumers receive in return for the premium. If this is known, then why consumers purchase health insurance will be known.

This is an important question because it can affect consumer welfare in fundamental ways. From the perspective of the insurance firm, if insurers knew precisely what it is that people value in insurance, they would be able to design more competitive insurance contracts, contracts that provide more of what consumers want to purchase. From a public policy perspective, policy makers would be able to design more efficient and effective government health insurance programs, implement more equitable subsidies and taxes, and encourage more efficient behavior with regard to the types and amount of health care insured consumers purchase. From a larger social perspective, if it were known why consumers purchase health insurance, politicians would better know the value of health insurance relative to other goods and services, and thereby better understand the importance of health insurance programs compared to all the other programs that government could sponsor.

Complexities Of Health Insurance

Although this might seem like a relatively straightforward exercise, it is not. Insurance contracts have a number of complexities that make them difficult to analyze. Here is a listing of the most important ones. It should be noted that many of these complexities were identified by Kenneth Arrow in his famous 1963 paper on the characteristics of the medical care portion of the economy that make the sector unusual.

First, there is the uncertainty with regard to illness itself: not everyone becomes ill during the contract period and many of the benefits that consumers derive from paying a premium occur only if they become ill. Payoffs that are contingent appear in many types of contracts so they are not unusual, but they always make things more complex because they require the consumer to think about what might happen in the future.

Second, because illnesses vary, there is uncertainty with regard to the cost of treating illness. Some illnesses require health care expenditures that are relatively affordable to the typical consumer, but other illnesses are catastrophically expensive. Not only do the costs of different illnesses vary, but also the resources available to individuals if they were to remain uninsured and had to pay for health care themselves. That is, some consumers who become ill are rich and some are poor. On top of that, the diseases and the procedures used to treat them may also reduce the budget if the consumer is no longer able to work and make income. The variation in economic circumstances of consumers interacts with the variation in the cost of the illness, and both conspire to make a large portion of health care expenditures unaffordable to a substantial segment of the population. This complexity must also be accounted for in the theory.

Third, uncertainty also occurs with regard to the effectiveness of the health care in treating the disease. Sometimes the health care cures the disease, and sometimes it does not. Indeed, sometimes the health care is represented only by the palliative care during the short period before death. Although the variability in the effectiveness of the health care is a consideration in the purchase of insurance, it is clear that modern health care is often effective and for that reason, can be very valuable to the consumer. Thus, the value of the health care covered by the insurance benefit is a consideration in determining why consumers purchase insurance. This is especially true in light of implication of the second complexity that sometimes the health care would not be affordable and thus accessible to the consumer without insurance.

Fourth, the contingent benefit of insurance is based on the consumer transitioning from a state of being healthy to a state of being ill. The change in health state clearly affects how one values medical care – what ‘healthy’ person would value chemotherapy or a leg amputation enough to ‘consume’ it? Sometimes, the change in health state can also affect how consumers value the other goods and services that can be purchased. For example, some illnesses can be in the form of a broken bone or a minor respiratory disease, where it is clear that one is feeling poorly on a temporary basis and the state of illness represents largely an inconvenience. Other illnesses, however, may have severe symptoms in terms of pain and ability to function normally, be chronic, or threaten the lives of the individuals suffering from them. Thus, when thinking about the value of all the benefits of an insurance contract, the consumer would likely need to consider how they would regard the benefits of insurance if they were filtered through the perspective of being in an ill state. In the ill state, consumers may appreciate the various aspects of life – both the medical care and the income to spend on entertainment, travel, and other consumer goods – differently than in a healthy state, and this would bear on how the benefits of insurance are perceived and evaluated. Theorists who desire to model why people purchase insurance would need to acknowledge this change in perspective in order to produce a complete theory.

Fifth, health insurance contracts are not perfect. Although we may think about illness as an exogenous event that we have no control over, in actuality, we have a great deal of control over whether we become ill. For example, whether we develop heart disease is associated with a number of discretionary behavioral choices – whether we smoke, are overweight, exercise, eat cholesterol-laden foods, etc. Insurance contracts (so far) do not distinguish between illnesses that are brought on by the behavior of the insured and those that are caused by factors beyond the control of the individual. The problem this creates for insurance is that sometimes being insured might alter the extent to which a consumer acts to avoid disease. ‘Moral hazard’ is the term that those in the insurance business use to describe the changes that occur in behavior of the insured and ‘ex ante moral hazard’ is the term used by economists to describe the type of behavioral change where the probability of becoming ill increases when an individual becomes insured.

Sixth, most health insurance contracts simply pay for the sick consumer’s health care. As a result, the amount of the insurance benefit when ill is not fixed in advance of becoming ill (nor is the benefit even totally dependent on becoming ill). Insurers often pay for more health care than the ill consumer would pay for if they had remained uninsured. ‘Ex post moral hazard’ is the term used to describe the type of behavioral change where once insured persons become ill, they purchase more health care and incur greater expenditures than they would if they were not insured and were paying for the care themselves.

And finally, the basic idea behind insurance is that many people who are not ill pay into a pool in order to benefit the few members of the pool who become ill during the period of insurance coverage. This means that one of the fundamental incentives for prospective purchasers of insurance is to try to join the pool ‘after’ one becomes ill, in order to avoid paying premiums during the years when one is not ill. This phenomenon is called ‘adverse selection’ and is represented by the tendency of those who purchase insurance to be sicker or more prone to becoming sick, and therefore more costly to insure, than the average person. If the insurer does not catch this bias and charge these people higher premiums, the firm would pay out benefits that are greater than the premiums it takes in. Again, health insurance contracts are not perfect.

Modern health insurance plans often provide other benefits – the ability to bargain down producer prices, the evaluation of new technologies for effectiveness, the screening of physicians and other providers for quality – that add to the complexity, but those that are listed above represent the major complexities associated with the quid pro quo of the traditional insurance contract. In the discussion that follows, we consider how improvements in our understanding of insurance have coincided with increases in the benefits that are recognized to derive from insurance. We begin, however, with the conventional theory that the demand for health insurance is simply related to the avoidance of the uncertainty associated with illness and the loss of income that paying for one’s own health care would entail.

Conventional Insurance Theory

The Gain From Certainty

The conventional theory of demand for ‘health insurance’ was originally borrowed from the theory of the demand for ‘insurance,’ which was concerned primarily with a type of indemnity policy where the consumer possesses a certain asset for which they desired protection from loss. For example, a homeowner might want protection from fire. The consumer has the choice between remaining uninsured and accepting the chance that the asset and its value might be lost to fire, or paying a premium for an insurance contract that would pay the consumer a lump-sum payment equal to the value of the asset if the asset were lost. Assuming that there is no difference between the premium payment and the expected loss if uninsured – that is, assuming that the insurance premium is actuarially fair and nothing extra is included in the premium to cover the administrative costs of the insurer – the consumer is better-off with insurance.

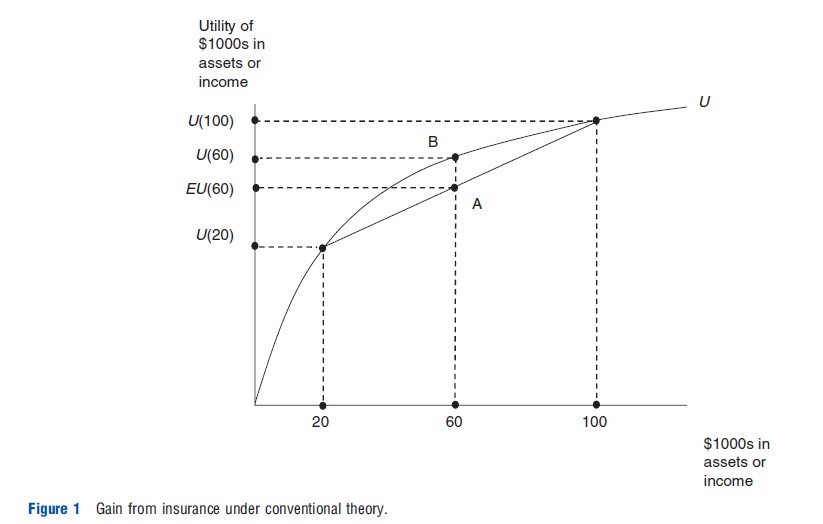

The insurance decision for this type of loss was laid out in 1948 by Milton Friedman and L. J. Savage in what has come to be regarded as the seminal article in the health economics literature (Friedman and Savage, 1948). Figure 1 shows the fundamental relationship that economists assume exists between utility, on the one hand, and either income or wealth, on the other. Utility increases with income or wealth, but at a decreasing rate. The shape of this curve, U, derives from that intuitively appealing principle that consumers would gain more utility from a given amount of additional income or wealth (that is, consumers would value or appreciate it more) if they were poor than if they were rich. For example, a consumer with $20 000 in wealth gains more utility from an additional $1000 than he would if he had started out with $100 000 in wealth.

The gain from purchasing insurance can be demonstrated using Figure 1. A consumer starts out with assets (or income, but for simplicity, the discussion will use assets) of $100 000 and is faced with a 50% chance of becoming ill and incurring a $80 000 loss due to the need to purchase a medical procedure. The utility function, U, indicates the utility of $100 000 is U($100 000) and the utility of $20 000 is U($20 000). Without insurance, the expected value of the consumer’s assets is $60 000 because he starts out at $100 000, but loses $80 000 with a 50% probability, so the expected loss is $40 000. Similarly, with regard to utility, without insurance, the consumer starts out at utility of U($100 000) but falls to U($20 000) with a 50% probability, so the expected utility is EU($60 000) as in Figure 1. Thus, point A represents the expected position of the uninsured consumer facing a loss of $80 000 with a 50% chance.

Assume that the insurer charges the actuarially fair premium, one that reflects only the expected payout and none of the administrative costs or profits. The actuarially fair premium is $40 000 because that is the amount that the insurer expects to payout for each person that is insured for this illness (that is, $80 000 payout times the 0.5 chance of illness, for each person who is insured). If the consumer pays such a premium and purchases insurance, she will have $60 000 regardless if healthy or ill. If the consumer stays healthy, she would start out with $100 000 in assets, would have no health care expenditures and receive nothing in payout from the insurer, but would pay a $40 000 premium, leaving $60 000 in assets. If the consumer becomes ill, she would start out with $100 000 in assets, would incur health care expenditures of $80 000, would receive $80 000 from the insurer, but must pay a $40 000 premium, again leaving $60 000 in assets. Thus, regardless of whether the consumer stays healthy or becomes ill, if she purchases this insurance, she has $60 000 in assets. The utility of $60 000 with certainty is determined by the utility function as U($60 000), and so with insurance, the consumer would be at point B in Figure 1. The gain in utility from insurance is measured by the vertical distance between points B and A, or the difference between U($60 000) and EU($60 000) on the vertical axis. This difference in utility is the welfare gain from buying health insurance under the conventional theory, and represents the sole reason for purchasing it under this theory.

To this theory was added the complexity of loading fees (the additional amount that the insurer includes in the premium to cover administrative costs and profits), but the basic source of the gain remained the same. Friedman and Savage interpreted this gain as satisfying the consumer’s preferences for certainty, as opposed to uncertainty, and many have viewed the benefits of health insurance from this perspective. Based on this theory and the utility gain from the certainty that health insurance contracts provide, Arrow concluded in his 1963 article that the case for health insurance was ‘overwhelming.’ This is the theory that has been used over the years to explain why consumers purchase health insurance.

Limitations Of The Theory

The theory, however, has a number of limitations. First, the theory would only apply to those medical procedures that are affordable. This is because there is no uncertainty if the loss cannot occur, and this would most likely be the case if the cost of the procedure is so high that the ill consumer cannot pay for care. It is possible that the consumer might be able to borrow the additional resources, but an uncollateralized loan for a risky procedure would be difficult to obtain and so this option is limited at best. Saving for the procedure is also possible, but saving when ill may be out of the question because of the ill consumer’s diminished earning capacity and the limitations on time available. Thus, this theory does not recognize that many procedures and health care episodes may be too expensive to be financed privately, save for insurance. This is an important omission because, given that about half of all health care expenditures in the US are incurred by the top 5% of spenders (Stanton and Rutherford, 2006) and that those under 65 in the lowest quartile of the income distribution in the US have virtually no net worth and those in the second lowest quartile of the income distribution have net worths that average close to their annual income (Bernard et al., 2009), procedures that are too expensive for consumers to afford to purchase privately make up a substantial proportion of health expenditures in the US.

Second, the ‘loss’ in this theory is the income or assets lost due to the spending on the medical care. In contrast to the simple destruction of an asset (e.g., a house burning down), the spending on medical care is not really a loss, but part of quid pro quo transaction where the consumer spends income or wealth to obtain medical care. The medical care that the consumer obtains in return for this ‘loss’ may be very valuable, but the value of the medical care does not appear in the model.

Third, the model assumes that the utility that the consumer gains from income or assets when ill is the same as the utility when healthy. For example, it assumes that $100 000 in assets is just as valuable when healthy and being spent on restaurant meals, gas for the car, etc., as it would be when ill and being spent on restaurant meals, gas for the car, and a $50 000 medical procedure that saves the consumer’s life. In fact, this model implicitly assumes that the utility from income is derived ‘only’ from the nonmedical care purchases that one can make with income, and that becoming ill does not alter at all the utility that is derived from these purchases. And as was noted, the utility from income that can be used to purchase medical care when ill simply does not enter the model.

Fourth, as mentioned, the motivation for purchasing insurance under this model was interpreted by Friedman and Savage to reflect the consumer’s natural preferences for certain ones over uncertain ones and that this preferences for certain losses summarized the reason why consumers purchase health insurance. Whether consumers actually do have a preferences for certain losses over uncertain ones has been tested by Kahneman and Tversky. In a series of experiments that led to the formulation of prospect theory (and to a Nobel prize in economics for Kahneman), these researchers found that consumers generally prefer uncertain losses to certain ones of the same expected magnitude, the opposite of what the conventional insurance theory asserted (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979). If this preferences for uncertain losses is generally true of consumers, as the experiments appeared to show, then the demand for health insurance cannot be attributed to a preferences for certain losses.

Fifth, the payoff in this theory is in the form of a lump-sum transfer of income to the insured. Although such a policy is possible and actually exists for some types of insurance, such as personal accident insurance (e.g., policies that pay $50 000 for the loss of sight in one eye), most health insurance policies pay off by paying for care (or a portion of it after some copayment by the insured). Moreover, spending (that is, the loss) with and without insurance is assumed to be the same in this simple model. As a result, this model does not allow for moral hazard.

Moral Hazard Welfare Loss

Of all the limitations of this risk avoidance model, the one that was seized on initially was the lack of recognition of moral hazard – but not all moral hazard, only ex post moral hazard. As mentioned earlier, economists distinguish between two types of moral hazards. Ex ante moral hazard occurs when the consumer takes less care to avoid losses if insured than if not insured. For example, because health expenditures are covered, a consumer might have an increased probability of illness if insured, compared with if uninsured. Ex post moral hazard was defined originally as the additional spending that occurs after one becomes ill, insured versus uninsured. Recently, some economists have suggested that ex post moral hazard is represented only by the portion of the change in this behavior that is due to a response to prices, but that was not the original view. This distinction has come about only recently, because for a long time it was thought that ex post moral hazard was ‘only’ a response to prices.

In a 1968 comment on Arrow’s (1963) article, Pauly wrote what was to become ‘one of the,’ if not ‘the,’ most influential articles in the health economics literature. Pauly’s article led to almost a ‘preoccupation’ among American health economists with the notion that the basic problem with the high health care costs in the US was the consumption of too much care (and, implicitly, not the high prices of health care). This perspective, in turn, led to important policy initiatives in the US over the next 30 or 40 years that focused on reducing the quantity of care: The introduction of copayments into insurance policies, the adoption of managed care, and the promotion of consumer-driven health care (where policies with large deductibles are paired with health savings accounts). Indeed, some economists argued during this period that high prices of medical care were beneficial because they choked off demand by making coinsurance rates more effective.

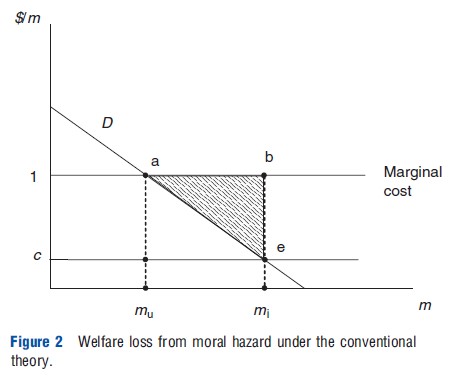

Pauly’s argument recognized that health insurance policies paid off not by paying a lump-sum amount when the consumer became ill, as the Friedman and Savage model assumed, but by paying for any health care that the individual consumed. Thus, the impact of insurance on the consumer’s behavior was essentially to reduce the price of health care, to which the consumer responded by demanding a greater quantity of care. Figure 2 shows the observed or Marshallian demand for health care, D, by the individual consumer and the quantity of health care consumed, mu, if uninsured and if 1 is the price of a unit of medical care, m. If the consumer becomes insured under a contract where the insurer pays for a percentage of care represented by (1–c) with c representing the coinsurance rate, then the price of care that the consumer faces effectively drops to c and the consumer purchases mi quantity of health care. So, ex post moral hazard is represented by the increase in consumption from mu to mi.

The problem with moral hazard according to Pauly’s model is that the additional care is worth less than the cost of the resources used to produce it. If the health care market is competitive, then the market price of health care, 1, would also represent the marginal cost of the resources used to produce the care, that is, the value of the goods and services that the same resources could have been produced in their next most valuable use. The marginal cost curve represents the cost of producing each of the units of health care, given the assumptions of the model. The value of health care is measured by the willingness to pay for it, as shown by the height of the demand curve at each level of m. For example, according to the demand curve, the willingness to pay for the mu unit of medical care is just equal to 1, the market price. If the price were to drop to c because of insurance, the additional health care consumed, that is, the moral hazard, is (mi – mu). The value of this additional care is represented by the area under the demand curve, area aemimu. The cost, however, is the area under the marginal cost curve, or abmimu. Costs exceed the value by the area abe. This area, then, represents the welfare loss associated with moral hazard.

Empirical And Professional Support

With the publication of Pauly’s paper, the conventional theory of the demand for health insurance was now set. The demand for health insurance was represented by the gain from averting the risk of loss, but it was necessary to subtract from this gain the welfare loss from ex post moral hazard. Pauly thought that the loss was potentially so important that the net effect, ‘could well be negative’ (Pauly, 1968, p. 534), implying that insurance could make the consumer worse-off, especially if the government mandated its purchase. In 1973, Martin Feldstein empirically estimated the net gain from health insurance in the US based on conventional theory and concluded that ‘‘the overall analysis suggests that the current excess use of health insurance produces a very substantial welfare loss’’ (Feldstein, 1973, p. 275). Feldstein argued that raising the coinsurance rate to 67% across the board would improve welfare. This view persisted over the remainder of the century and into the next. In 1996, for example, Willard Manning and Susan Marquis found that low coinsurance rate health insurance policies also resulted in a net welfare loss based on conventional theory and concluded that a coinsurance rate of approximately 45%, also across the board and with no limit on out of pocket spending, would be optimal.

During the same period, a health insurance experiment – the most costly social experiment ever performed in the US – was also conducted by the RAND Corporation. The RAND Health Insurance Experiment randomly assigned some participants to receive free care and others to care with some form of cost sharing. As was expected, those assigned to free care consumed more medical care – both physicians services and hospital admissions – than those who had to pay for a portion of the cost of their care, but more importantly, aside from better correction of vision problems, there was no significant improvement in health for those who received more care (Newhouse, 1993). Thus, the influential findings of the RAND health insurance experiment fit the Pauly’s model like a glove: Insurance generated additional care, but the additional care was not very valuable because it did not result in any important improvements in health.

Why Pauly’s focus on ex post moral hazard caught on among American economists is not clear: after all, two other sources of inefficiency in health insurance contracts – ex ante moral hazard and adverse selection – were also broadly recognized at the time. Ex ante moral hazard would have generated a similar welfare loss from the reduction in purchase of efficient health preservation services and the increase in the purchase of inefficient health recovery services once ill (medical care), because the prices of the recovery services were made to be artificially low relative to the prices of the health preservation activities. The inefficiency associated with adverse selection (the nonpurchase of insurance by those who would have purchased insurance were it not for the high premiums caused by adverse selection) was also broadly recognized at the time, but this inefficiency did not rise to the level of a component of the basic theory. Although the confirmatory studies by influential economists were clearly a factor, perhaps even more important for its appeal was that it underscored the importance of competitive prices, which was consistent with the prejudices of economists. Moreover, its diagrammatic argument was accessible, elegant, and easily taught.

Alternative Theory

The Gain From An Income Transfer When Ill

Recently, an alternative theory has been suggested that incorporates all the factors that were limitations to the conventional theory (Nyman, 2003). The basic notion is that health insurance represents a quid pro quo contract where the consumer pays an actuarially fair premium to the insurer when healthy in order to receive a lump-sum income payment if the insured were to become ill during the period of time covered by the insurance contract. If the insured consumer does not become ill, the contract holder simply relinquishes the insurance premium. An actuarially fair health insurance contract is therefore purchased because the utility gained from the additional income if ill exceeds the utility lost from paying the premium if the consumer remains healthy.

This theory is fundamentally different from the Friedman and Savage theory because it does not incorporate a designated loss when ill as part of the insurance decision. That is, there is no loss of assets or income from illness recognized by the theory. As a result, there is no ‘ preferences for certainty’ in this model and no ‘smoothing of income’ across the states of the world, as some have interpreted the Friedman and Savage approach to imply. The only loss of income that occurs in the alternative model is the loss of the insurance premium if the insured person remains healthy. Because the theory does not incorporate a designated loss, the income payment when ill can be any amount and does not need to reflect the spending that would occur without insurance.

Advantages Over Conventional Theory

This theory has a number of advantages over conventional theory. First, the theory is not limited to explaining the demand for insurance coverage for only that portion of medical care that the consumer could otherwise purchase if uninsured (the portion that would generate a loss of income and/or wealth due to such spending), but it also explains why consumers purchase insurance coverage for medical care spending that would exceed the consumer’s resources. Indeed, the access that the insurance payoff provides to that medical care that would otherwise be unaffordable is one of the main reasons why insurance is purchased under this alternative theory.

Second, the value of insurance is directly linked to the value of the medical care that the consumer can purchase as a result of being insured and receiving an income payoff when ill. As was mentioned, some modern medical care is ineffective, but much of it is very effective and can generate large health improvements, both in terms of limiting the negative effects of illness and expanding life expectancy. The health improvements derived from this medical care can be very valuable to consumers, and there is often no alternative (private) means for obtaining this care other than to purchase insurance. This value, entirely missing from the conventional model, is emphasized in the alternative model.

Third, this model recognizes that consumer preferences can be altered when the consumer becomes ill by specifying two utility functions for both consumer commodities and medical care: one when healthy and another when ill. This allows for the consumer to incorporate a different evaluation of consumer goods and services in the two states. For example, is spending on traveling or home improvements as valuable when ill as when healthy? But, more importantly, it allows for a different evaluation of medical care by the consumer in the two states. For example, is spending on a new heart valve or leg amputation as valuable when healthy as when ill? It recognizes that illness changes preferences so that a coronary bypass procedure or course in chemotherapy now becomes valuable, whereas it would reduce utility if purchased when healthy. Under this theory, insurance is the mechanism by which an increase in income occurs at precisely the same time as the onset of illness generates a change in preferences , making it possible to purchase the medical care services that would not be valued or purchased, given preferences when healthy.

Fourth, rather than trying to explain the purchase of insurance by claiming that consumers generally exhibit a preferences for certain losses over uncertain losses of the same expected magnitude – a claim that has been thoroughly discredited and indeed proved to be diametrically opposed to the preferences of most consumers by the empirical studies underlying prospect theory – the alternative theory suggests that preferences for certainty are not part of the demand for health insurance at all. Uncertainty exists in life, clearly, but insurance cannot do anything about it other than to coordinate the uncertain occurrence of illness with an equally uncertain payment of income.

Fifth, the conventional theory focuses on a welfare loss from ex post moral hazard, all of which is deemed to be welfare decreasing because it is generated by a reduction in price and a subsequent movement along the consumer’s demand curve with a payment of income. It is as if a hospital suddenly announced a sale on coronary bypass procedures and additional shoppers flocked to take advantage of the bargain, whether they were ill and needed a bypass operation or not. With the alternative theory, the price reduction is the vehicle by which income is transferred from those who purchase insurance and remain healthy to those who purchase insurance and become ill. As a result, the price reduction applies only to those who are ill enough to need an important health care intervention and the income transfer within the price reduction works to shift out the demand curve of those who are ill. It is as if a hospital suddenly announced a sale on coronary bypass operations and those additional patients who now flocked to the hospital are only those who suffered from coronary artery disease and could not afford to purchase the procedure at the existing market prices.

Welfare Implications Of Moral Hazard

Actually, the moral hazard response to the price reduction under the alternative theory requires some additional explanation because it can be partly a response to the price decrease that is used to transfer income and partly due to the income transfer itself. Indeed, this is one of the important implications of the new theory: Some of the additional spending due to insurance (moral hazard) is efficient and due to the income transfer, and some is inefficient and due to using the price reduction to transfer income. It is the efficient moral hazard that represents one of the most important reasons for purchasing insurance. At the same time, inefficient moral hazard also exists, but it is not quite the same as described by Pauly (1968). A short explanation is required.

As described earlier, conventional theory suggests that the response to insurance can be described as a movement along the observed or Marshallian demand curve. In Figure 2, at the market price, 1, a certain amount of medical care, mu, is demanded. If insurance was purchased, the price of medical care faced by the consumer is c, then mi would be purchased. Thus, conventional theory uses the Marshallian demand curve to show the response to insurance. With insurance, however, the price does not simply drop due to exogenous market forces as would be consistent with the Marshallian demand, but instead, the price reduction must ‘be purchased’ by paying the premium for an insurance contract. Moreover, the greater the price reduction or lower the coinsurance rate specified in the contract, the greater the premium that must be paid. The payment of the premium reduces the amount of income remaining that can be used to purchase medical care after insurance is purchased, and thus reduces the amount of care that is purchased at the lower insurance price. (Medical care is a ‘normal good’ implying that less would be purchased if the consumer had less income.) For example, for a family of 4 making $40 000, an 80% reduction in the price that occurred as a result of market forces would generate a greater increase in the quantity of medical care purchased than would an 80% reduction in the price which the family had to pay for with a $20 000 health insurance premium. This implies that the insurance demand curve is steeper than the Marshallian demand curve used by Pauly, and that the actual moral hazard welfare loss is smaller than would be the case if evaluated by a movement along the Marshallian demand curve.

More importantly, however, the price reduction is the mechanism used in the insurance contract to transfer income out of the insurance pool to the consumer who has become ill. For example, without insurance, a consumer who contracts breast cancer would spend $20 000 of her own money on a mastectomy. If she purchased an insurance contract for $6000 that lowered her price to 0, she would purchase the $20 000 mastectomy, plus the $20 000 breast reconstruction and two extra days in the hospital to recover for $4000, all paid for by the insurer. The additional $24 000 in spending on the breast reconstruction and the two extra days in the hospital represents the moral hazard. Although the price has fallen to 0 to the consumer, the price of the care that the hospital and physicians provide has not changed, and $44 000 must come out of the insurance pool to pay for her care. Of that amount, $6000 represents the premium that she paid originally, but the rest, $38 000, represents the premiums that others paid into the pool and that were used to pay the providers on her behalf. These payments represent a transfer of income to her. If the insurance contract was such that this income transfer were paid directly to the consumer upon becoming ill, it would cause the consumer to purchase more medical care than if uninsured, and thus generate a portion of the moral hazard.

Indeed, by comparing the total moral hazard under a standard insurance contract to the moral hazard under a contract that paid off with a lump-sum equal to the same income transfer, one can distinguish the efficient moral hazard from the inefficient moral hazard. If the insurer had paid off by writing a check to the consumer for $44 000 upon the diagnosis of breast cancer, this additional income may have caused the consumer to purchase the $20 000 breast reconstruction, but not the two extra days in the hospital for $4000. If this were the case, then the $20 000 breast reconstruction would represent efficient moral hazard because the consumer could have used the additional income to purchase anything of her choosing. So, if she chooses to purchase the medical care, one can assume that the additional income has shifted the preinsurance demand curve outward and that the willingness to pay now exceeds the cost of producing the care. The $4000 for the extra hospital days is inefficient and consistent with Pauly’s original concept.

Conventional Versus Alternative Theories Of Moral Hazard Welfare Compared

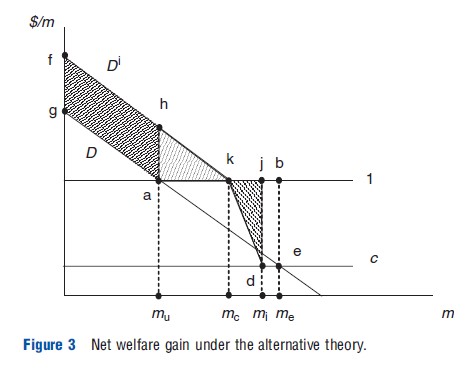

The alternative theory can now be compared directly with the conventional theory of the moral hazard welfare loss. In Figure 3, the Marshallian demand curve D shows the response to an exogenous change in the price for the consumer who has become ill. At a medical care price of 1, the consumer, if uninsured, would consume mu medical care. If the price had fallen to c exogenously, me would be purchased, but that would not represent the response to ‘purchasing of a price of c’ through an insurance contract. Purchasing a price of c through an insurance contract would have generated a smaller demand response because income in the amount equal to the premium payment is no longer available to use in purchasing medical care at the lower insurance price, c. The effect is to make the insurance demand steeper and to reduce spending from me to mi. And as increasingly lower insurance prices (cs) are purchased, the difference between the Marshallian demand and the insurance demand would increase, because of the increasingly greater insurance premiums charged for lower and lower coinsurance rates. At the same time, the effect of the income transfer would shift the Marshallian demand curve to the right, Di, exhibiting this shift directly for all prices above 1, but for prices below 1, both the price and income transfer effects together would be manifested as a simultaneous movement along an increasingly steeper demand curve and a shifting of that portion of the curve to the right.

If a price of c were purchased with the insurance contract, the additional medical care that would be purchased because of using a price reduction to transfer income is represented in Figure 3 as (mi – mc). The welfare loss from this purchase can be represented by triangle kjd. The shifting out of the demand curve caused by the income transfer to Di would result in (mc– mu) additional medical care purchased, relative to the amount that would have been purchased if uninsured. This additional medical care has a welfare value, that is, an increase in the consumer surplus equal to triangle hka. In addition, the transfer of income through insurance would increase the willingness to pay for all the care that was being purchased without insurance, resulting in an increase in the consumer surplus of area fhag. In contrast, under the conventional theory, there would only be a welfare loss defined by a movement along the Marshallian demand and equal to area abe.

Implications Of The Alternative Theory

The implications of the alternative theory are far-reaching, and contrast dramatically to the implications of the conventional theory. Here are some of them.

First, not all moral hazard is welfare decreasing. Some moral hazard purchases are efficient and some are inefficient, and the challenge for policy is to distinguish one from the other in order to apply cost sharing only to the inefficient moral hazard. Thus, the theory is consistent with the concept of value-based insurance design which attempts to apply coinsurance rates only to those areas of insurance coverage that are to be discouraged, and not to others. Contrast this to the policies supported by conventional theory to apply high coinsurance rates to all types of medical care across the board, and with no limit on out-of-pocket spending, in order to reduce all moral hazard spending.

Second, health insurance is more valuable than has been deemed so under conventional theory because of the explicit recognition that insurance provides access to expensive health care that would otherwise be unaffordable and for which there would be no alternative way to access privately. That is, insurance is valuable precisely because of the additional care that it allows the ill consumer to purchase. Indeed, it has been argued that the RAND Health Insurance Experiment was biased by attrition and that the attrition accounts for the lack of a health effect from the reduction in health care use, especially hospitalizations, among the participants assigned to the cost-sharing arm. This means that, far from being welfare decreasing, insurance is welfare increasing, and government programs designed to insure the uninsured represent beneficial public policy.

Third, an insurance policy that pays-off by paying for care represents a stand-in for a contingent claims insurance policy that would pay off by making a lump-sum income payment upon diagnosis. Although there may be a moral hazard welfare cost from the prevalent use of the standard policy, it is likely that the welfare cost of a contingent claims policy would be higher. For example, before a claim could be paid, the insurer would need to hire physicians or other health professional to review each claim and verify that the claimant actually had the claimed diagnosis. Moreover, to specify the various payment adjustments that would be required in the event of the various complications or adverse events that could occur with a diagnosis and its treatment, the insurer would need to hire a number of lawyers, actuaries, economists, accountants, and others to write the contracts and to keep them updated in light of scientific advances, price increases, and other changes that would necessitate adjustments in the payoff. If the moral hazard welfare costs in a standard insurance policy represent the transactions costs of transferring income to those who become ill and if the level of these costs in the standard policy is the lowest of any type of policy, then these costs can essentially be ignored as a necessary inefficiency.

Fourth, by focusing on the moral hazard welfare loss, conventional theory led economists to focus on solutions to the health care cost problem in the US that were related to reducing the quantity of medical care, rather than reducing the price of care: applying coinsurance rates and deductibles, moving to managed care and promoting consumer-driven health care insurance arrangements. These policies seemed to work. Using recent Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development statistics for the Group of 7 (G7) countries (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the UK, and the US), it can be shown that Americans went to the doctor about half as often and spent half as many days in the hospital as citizens of the other G7 countries. Nevertheless, the US spent over twice as much per capita as the comparable average for the rest of the G7 countries. One interpretation of this is that by focusing on the moral hazard welfare loss, conventional theory misled economists to focus on the solutions that would reduce the quantity of health care consumed, when the more important source of the health care cost problem in the US was high prices that were generated by the monopoly power of providers.

References:

- Arrow, K. J. (1963). Uncertainty and the welfare economics of medical care. American Economic Review 53, 941–973.

- Bernard, D. M., Banthin, J. S. and Encinosa, W. E. (2009). Wealth, income, and the affordability of health insurance. Health Affairs 28, 887–896.

- Feldstein, M. S. (1973). The welfare loss of excess health insurance. Journal of Political Economy 81, 251–280.

- Friedman, M. and Savage, L. J. (1948). The utility analysis of choices involving risk. Journal of Political Economy 66, 279–304.

- Kahneman, D. and Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 47, 263–292.

- Newhouse, J. P. and the Insurance Experiment Group (1993). Free for all? Lessons from the RAND health insurance experiment. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Nyman, J. A. (2003). The theory of demand for health insurance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Nyman, J. A. (2007). American health policy: Cracks in the foundation. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 32, 759–783.

- Pauly, M. V. (1995). When does curbing health care costs really help the economy? Health Affairs 14, 68–82.

- Pauly, M. V. (1968). The economics of moral hazard: Comment. American Economic Review 58, 531–537.

- Stanton, M. W. and Rutherford, M. K. (2006). The high concentration of U.S. health care expenditures. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.