Introduction

There is an enormous literature evaluating and comparing health insurance systems around the world, which this article attempts to synthesize while emphasizing systems in developed countries. The authors’ approach is to provide an overview of the dimensions along which health insurance systems differ and provide immediate comparisons of various countries in tabular form. To organize their analysis, they focus their discussion on coverage for the largest segment of the population in all developed countries: workers under the age of 65 years earning a salary or wage, which they call the primary insurance system. They later touch on the features of special programs to cover the elderly, the poor or uninsured, and those with expensive, chronic conditions. They do this not because these groups are less important, but rather because special programs are often used to generate revenue and provide services to these groups, and including these programs in their discussion adds considerable complexity. For the same reason, they also focus on primary insurance coverage of conventional medical care providers – office-based physicians, hospital-based specialists, general hospitals, and pharmacies – knowing that there are many specialized insurance programs for long-term care, specialty hospitals, informal providers, and certain uncovered specialties.

A key feature of their analysis is that they focus on providing a broad framework for evaluating different systems rather than immediately comparing specific countries. They initially distinguish between the alternative contractual relationships used in different insurance settings and the choices available to each agent or decision maker. They then provide an overview of the alternative dimensions in which healthcare systems are commonly compared, which include the breadth of coverage, revenue generation, revenue redistribution across health plans, cost control strategies, and specialized and secondary insurance.

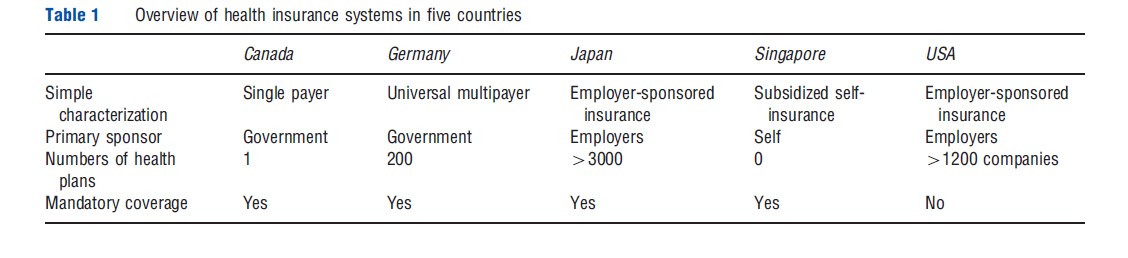

Throughout the article, the authors use the health insurance systems of Canada, Germany, Japan, Singapore, and the USA. As shown in Table 1, insurance systems in these five countries span much of the diversity exhibited by health insurance systems around the globe. These countries include both: the most expensive system (US) and the least expensive (Singapore); single payer as well as multiple insurer; and government-sponsored and employer-sponsored insurance. Unlike many comparisons, the authors try to emphasize the general nature of the institutions used to provide care rather than the specifics of the institutional arrangements. More unified discussion of each country is reserved until after they characterize the dimensions in which healthcare systems can be compared.

Agents And Choices

Agents

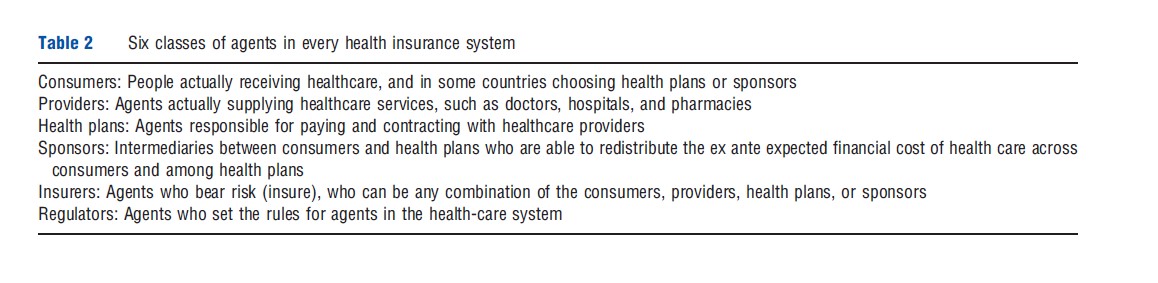

As summarized in Table 2, it is useful to distinguish six classes of agents in all health insurance markets. Consumers are agents who receive healthcare services, but in some systems they may have other choices to make. Providers actually provide information, goods, and services to consumers and receive payments; the article focuses on providers covered by insurance contracts. Health plans are agents who contract with and pay providers, also known in some countries as sickness funds. The sponsor in a health system serves as an intermediary between consumers and health plans, allowing for consumer contributions for insurance to differ from the ex ante expected cost of healthcare across consumers. In most countries, the sponsor is a government agency, although in the USA and Japan the sponsor for most employed workers is their employer. The key role of the sponsor in most countries is to ensure that the insurance contribution by a consumer with high expected costs (such as someone old, chronically ill, or with a large family) is not many times larger than the contribution of a consumer with low expected costs. Despite the enormous complexity of diverse intermediaries in many health insurance systems, consumers, providers, health plans, and sponsors can be viewed as the fundamental agents in every healthcare market.

Two other types of agents deserve mention. Insurers are agents that bear risk in their expenditures. In a given system, they can be identified by asking who absorbs the extra cost of care from a flu epidemic or accident. The insurer is not always a health plan as many health plans do not actually bear risk, but instead simply contract with and pay providers and pass along the expense to someone else. Insurance (or risk sharing) in a healthcare system can be shared by any of the four main agents in the healthcare system. Finally, regulators set the rules for how the healthcare and insurance market is organized, and this role can be played by sponsors (e.g., government), health plans, or providers (such as the American Medical Association in the US). Sometimes the functions of two or more agents are combined in the same agent. For example, some health plans own hospitals, and hence are simultaneously a health plan and a provider.

Systems Of Paying For Healthcare

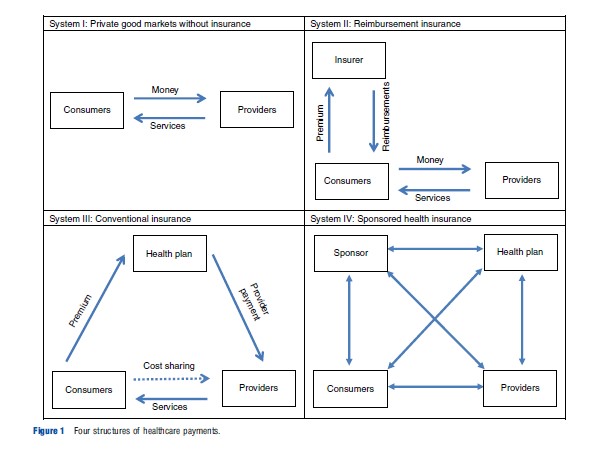

Fundamentally, there are four different ways of organizing payments and contracts in healthcare systems. Schematic diagrams of these are shown in Figure 1. System I is a private good market, in which consumers buy healthcare services directly from providers. This system is still used in all countries for nonprescription drugs and many developed countries for certain specialized goods (e.g., routine dental and eye care, and elective cosmetic surgery,) but is rare for the majority of healthcare services. Most consumers in Singapore and uninsured consumers in the US rely on a private good market, and pay for their healthcare when needed, without insurance.

System II is a reimbursement insurance market, in which consumers pay premiums directly to an insurer in exchange for the right to submit receipts (or ‘claims’) for reimbursement by the insurer for spending on healthcare. Under a reimbursement insurance system the insurers need not have any contractual relationship with healthcare providers, although the insurers will need rules for what services are covered and how generously. As will be seen, System II is the most common for secondary insurance in developed countries, and it is also widely used for automobile and home insurance.

System III is a conventional insurance market in which the consumer pays a premium to a health plan, which in turn contracts with and pays providers. Although popular in theoretical models of insurance System III is not used for the primary insurance system in any developed country, but is sometimes used for secondary insurance programs. Note the key difference in incentives between these two systems: System II incents the consumer, but not the health plan, to search for low price, high-quality providers, whereas System III does the reverse, reducing consumer incentives but enabling the health plan to negotiate over price and quality.

System IV is a sponsored insurance market in which the revenue is collected from consumers (directly or indirectly) by a sponsor who then contracts with health plans, who in turn contract with and pay providers. All developed countries that were studied involve a sponsor, although in some developing countries the sponsor may be a health plan.

Choices

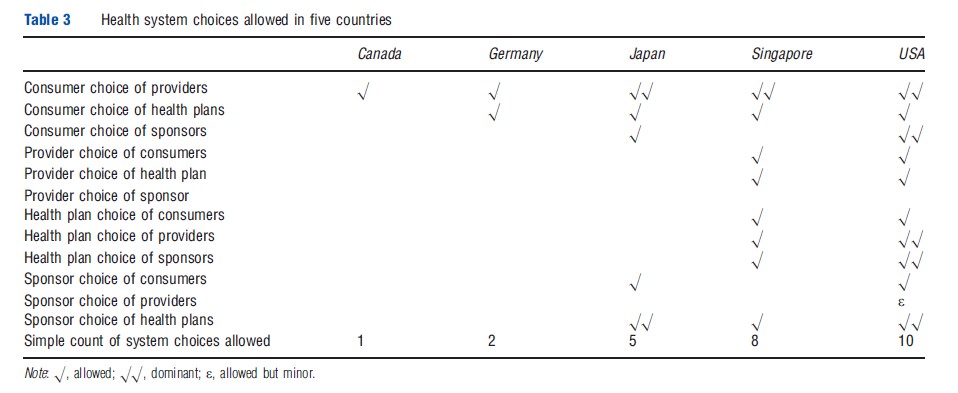

Each of the line segments shown in Figure 1 reflects a contractual relationship, in which money or services are transacted. These relationships are generally carefully regulated. Countries differ in the extent to which they restrict or allow choice in each of these contractual relationships. Although many comparisons of international insurance systems do not emphasize these choices, they vary across countries significantly. Table 3 summarizes them for the five countries that are the focus of this article.

Every developed country insurance system allows consumers to choose among multiple providers, but only a few allow providers to turn down consumers, or charge fees above the plans’ allowed fees (Singapore, the US). In some countries (notably the US, and legal but rare in Germany), health plans may choose which providers they want to contract with, and providers may in turn choose the health plans they contract with (selective contracting). An especially important dimension of choice is whether the primary system has more than one health plan (Germany, Japan, the US), and how choices among health plans are regulated. In countries like the US and Japan, employers implicitly choose who to sponsor when they hire workers, and hence employers play a key role in redistributing the costs of healthcare between young and old, healthy and sick, or small and large families. In the US, consumers and their sponsors (employers) are allowed to choose not to purchase any insurance at all; some Japanese consumers ignore the mandate and do not purchase insurance, making it similar to the US. The 2010 US Affordable Care Act (ACA) will start imposing tax penalties on consumers and employers in 2014 if they do not purchase insurance, but the system will remain voluntary.

Breadth Of Coverage And National Expenses

Breadth Of Coverage

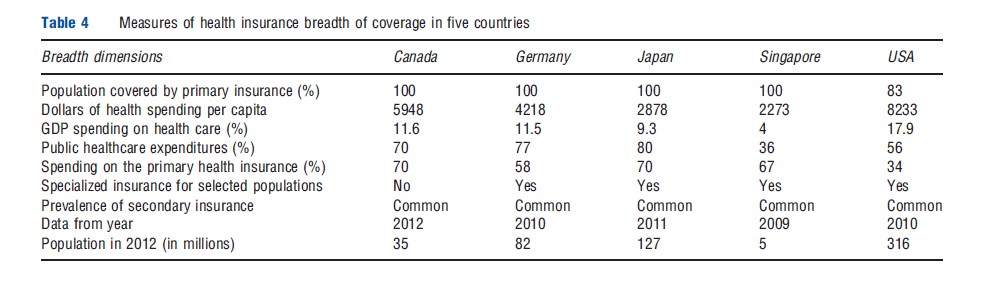

With the exception of the US, all developed countries have universal coverage for their own citizens through their primary insurance programs. As shown in the first row of Table 4, insurance coverage approaches 100% of the population in Canada, Germany, Japan, and Singapore, whereas only 83% of the US population has coverage. The 2010 ACA in the US will increase the percentage covered, but there is considerable uncertainty about how much coverage will increase.

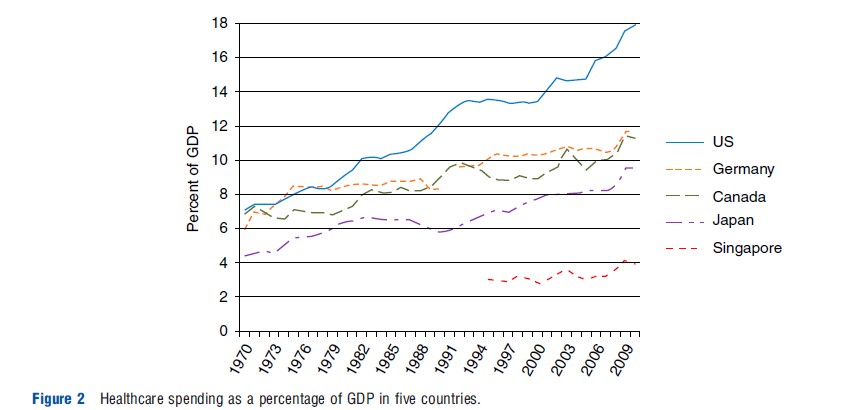

Because these measures are often a focal point of international comparisons of healthcare systems, Table 4 also contrasts the dollars per capita and percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) spent on healthcare. US spending of US$8233 per capita (18% of GDP) is by far the highest, whereas Singapore’s spending of US$2273 per capita (4% of GDP) is by far the lowest. In recent years, not only has the US been the most expensive, but it has also been experiencing more rapid cost growth relative to a share of its GDP (Figure 2).

Countries differ considerably in the proportion of their healthcare spending done by the public versus the private sector. This dimension is commonly a focus of international comparisons, but the proportion is not a direct choice of the country, rather it is the result of all of the other choices and regulations made in the country. Of greater interest is the percentage of spending by the primary health insurance plan or plans. This ranges from 70% in Canada to 34% in the US. Also of interest is the relative importance of the primary insurance program versus various specialty insurance programs. The US has specialized insurance programs for the elderly, the poor, children, and persons with disabilities, which collectively accounts for 56% of total healthcare spending.

Revenue

Revenue Generation

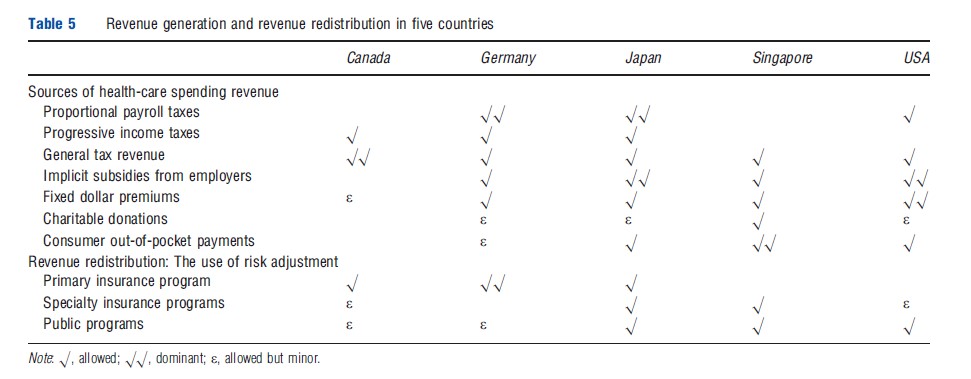

Developed countries vary significantly in how they generate revenue used to fund health plans (Table 5). In most countries, proportional or progressive taxes earmarked for healthcare are used as the primary source of revenue (e.g., Canada, Germany, Singapore, and Japan), although in some cases general tax revenues predominate. In the US and Japan, because employers are the primary sponsors, revenue comes from premiums paid by each worker. In the US, the premium is typically shared between the employer and the employee with the employer being free to choose the portion of the premium paid by the employee. State and federal tax systems partially subsidize health insurance in the US, by allowing these health insurance contributions to be exempt from income taxes, a widely discussed subsidy of health insurance and potential distortion. In Japan and Germany, premium contributions are set by law at a fixed rate, which is evenly split between employees and employers.

Revenue Redistribution

In countries with a single health plan option, there is no need for redistributing revenue between multiple health plans. However, such systems typically have to allocate budgets among different geographic areas, a similar task to reallocating money between competing health plans. In Canada, explicit risk adjustment formulas are used to allocate funds among geographic areas within each province. In systems with multiple competing health plans (i.e., Germany, Japan, the US) risk adjustment is sometimes used to redistribute money away from plans enrolling predominantly healthy enrollees and toward plans that enroll disproportionately sick or high-cost enrollees. Explicit risk adjustment for this purpose is done only in Germany, where age, gender, and diagnoses are used to reallocate money among competing plans. In the German system, redistribution is done not only to adjust for health status, but also to undo unequal revenues due to the average income of health plan enrollees. This is due to the fact that plans enrolling predominantly high-income enrollees will have greater revenues than plans with low-income enrollees, as a proportional payroll tax is used as the dominant revenue source.

Despite having multiple competing health plans, Japan and the US do not use risk adjustment to redistribute revenue, although in the US the ACA will expand the use of risk adjustment to the individual and small group markets. Risk adjustment is already used extensively in the various US public programs offered to the elderly and disabled populations and plans serving low-income and high-medical cost consumers.

HealthCare Cost Control

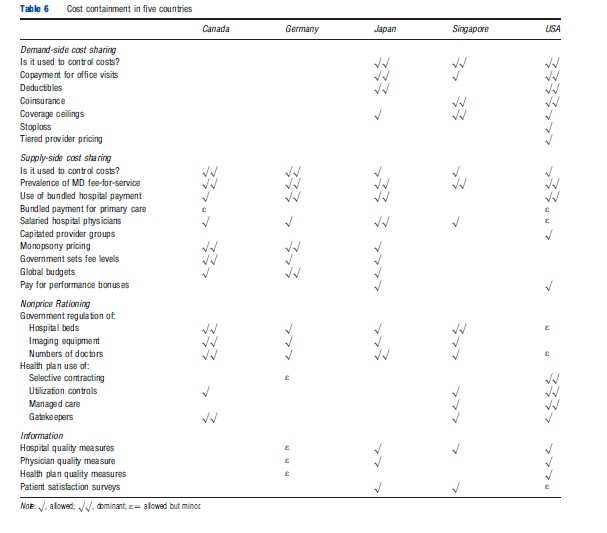

Although every country faces the challenge of controlling healthcare costs, countries vary significantly in their methods for doing so. Fundamentally, there are only four broad strategies for controlling healthcare costs: demand-side cost sharing, or using prices imposed on consumers to encourage them to reduce utilization; supply-side cost sharing, or using prices paid to suppliers to reduce utilization and/or reduce plan payments per unit; nonprice rationing, or setting limits on the quantity of key resources available to provide healthcare, whether done by the government sponsor or by individual health plans; and information provision that influences care provision and demand.

Table 6 summarizes the various cost control features used in the five countries that the article focuses on. It is interesting to note that Japan and the US rely extensively on demand-side cost sharing to control costs, whereas Canada and Germany rely heavily on supply side cost sharing. Singapore utilizes both. A growing number of countries have moved to bundled payment for hospital care, which originated in the US where hospital payments are based on Diagnosis Related Groups (DRGs). This system is now used in Germany, Japan, and many other countries. Experimentation with other forms of bundled payment, such as for primary care and multispecialty clinics, is ongoing but not yet widespread in Canada and the US.

Nonprice rationing techniques are used quite differently in the different countries. In Canada, gatekeepers and provinciallevel restrictions on capacity are common. In the US, the government uses these tools very little, though many private health plans use selective contracting and some managed care plans use gatekeepers, though they are rarely mandatory. Gatekeepers are rare in Germany, Japan, and Singapore. Consumer information about hospitals, doctors, and health plans is of growing availability in the US and Japan, but rare or nonexistent elsewhere.

Specialized, Secondary, And Self-Insurance

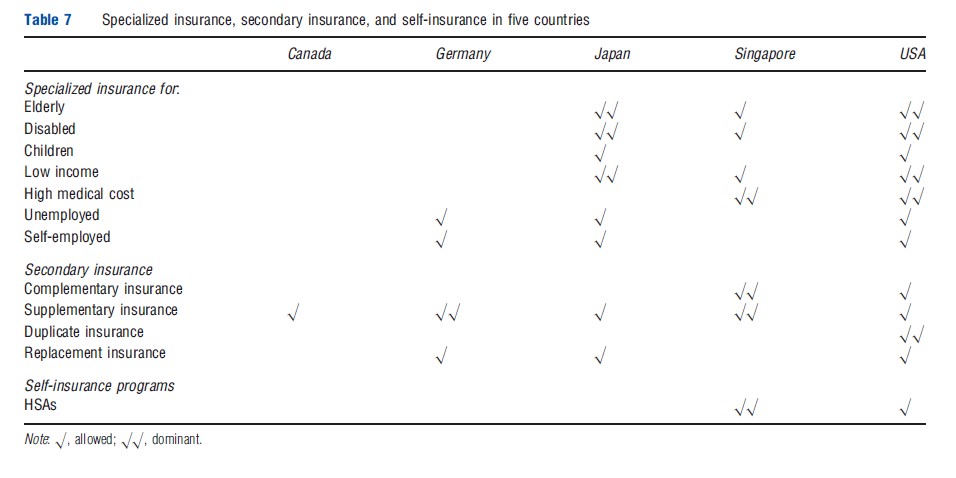

So far the focus has been on characterizing the primary insurance mechanism used by employed adults in each country. Some countries have separate specialized insurance programs, for which only certain individuals are eligible, such as the elderly, people with a serious disability, children, low-income individuals, individuals with high medical costs, the unemployed, the self-employed, and individuals employed in small firms. In some cases, these programs cover a sizable fraction of the population and an even higher fraction of total healthcare spending. As shown in Table 7, specialized insurance programs are very common in the US and Japan. At the other extreme, Canada, with its universal, largely tax-funded system, does not need any specialized programs for subsets of its population.

In addition to specialized insurance for which only certain individuals are eligible, many countries have secondary insurance programs that reduce the cost to consumers for spending not covered by the primary insurance policy. This can be of four forms: supplementary insurance covers services not covered under the primary insurance; complementary insurance provides additional reimbursement for services not covered by the health plan; duplicate insurance provides coverage for services that are already included in the primary insurance program; and replacement insurance serves as a substitute for primary health insurance coverage. Although conceptually distinct, in some countries, a single insurance policy may have elements of all three. In Australia, for example, a single private policy may cover out-of-pocket costs for some services (complementary), cover new services (supplementary), and also allow the enrollee to opt out of using the public insurance system for a specific hospitalization or service (duplicate). Germany allows specified high-income households to purchase replacement policies instead of the primary policy.

The type of secondary insurance available in a country depends on the regulatory environment and the structure of the primary insurance mechanism. For example, replacement insurance is banned in Canada, but encouraged in the US for elderly or disabled Medicare enrollees. In countries where primary health insurance does not utilize consumer cost sharing, consumers will have no incentive to purchase complementary insurance. Almost every health insurance system will create a demand for supplementary insurance, i.e., coverage for services not covered by the primary policy. Chiropractic care, dental care, optometry, physical therapy, and pharmaceuticals are common examples of services excluded from primary insurance but often covered by supplementary insurance. Coverage for nonhospital-based prescription drug spending is in some cases covered in the primary policy (Germany, Japan, and some Canadian provinces) but not in others (many US plans, Singapore), though in Singapore there is a short list of prescription drugs that can be obtained free of charge from approved providers.

A relatively unusual alternative for insurance is self-insurance, in which consumers are required or encouraged to save for their own current and future medical expenses. Self-insurance is typically encouraged through a tax-exempt health savings account (HSA). This mechanism is particularly important in Singapore, where health spending from HSAs comprises the majority of total healthcare spending. HSAs also received increased tax preferences in 2003 in the US, and in 2012 were used by approximately 4% of all Americans. The institutional structure of HSAs varies between the US and Singapore, but both have a common point, in that consumers are encouraged through the tax system to put money in when young. For most consumers the account will grow over time. In some systems (Singapore), unspent money in the account can be used for other household members, or spent on education, housing, or other retirement consumption.

The attraction of self-insurance is that consumers purchase healthcare services with money that is valuable to them, and hence they have more incentive to shop around. The experience of Singapore, discussed further below, provides evidence that the savings can be substantial. However, the challenges of self-insurance are numerous. First, it presupposes that consumers can become enough well informed to shop around intelligently. This is unlikely in most countries where there is inadequate price and quality information for consumer shopping. Countries such as Canada and Germany, which do not use demand-side cost sharing, demonstrate that supplyside incentives can be equally or more effective than demandside cost sharing. Also of concern is that self-insurance works well only for the 80% or so of the population with below average healthcare costs. Individuals with the highest healthcare costs, particularly those with chronic conditions, will tend to spend all of the money in their HSA, and be severely constrained in their ability to afford healthcare. In effect self-insurance fails these consumers when they need it most. Finally, self-insurance raises equity concerns. Studies show that wealthier households accumulate far more resources than low-income households and the tax-advantaged savings are of much lower value to low-income households. Together, both imply that most of the benefits of HSAs go to relatively healthy, higher-income households.

Country-Specific Comparisons

Canada

Canada has a universal single-payer, sponsored health insurance system called Medicare, which is administered independently by the 13 provinces and territories. Every citizen and permanent resident is automatically covered. The only choice available to consumers in the primary insurance system is a choice of providers. The only provider choice is whether to be in the dominant public system, or be an independent private provider, which is rare of most specialties. As of 2012, Canada spends approximately 11% of GDP on healthcare expenditures. Medicare provides medically necessary hospital and physician services that are free at the point of service for residents, as well as some prescription drug and long-term care subsidies. In addition to Medicare coverage, most employers offer private supplemental insurance as a benefit to attract quality employees, and a few Canadians purchase replacement insurance. Each province/territory is responsible for raising revenue, planning, regulating, and ensuring the delivery of healthcare services, although the federal government regulates certain aspects of prescription drugs and subsidizes the provinces coverage of services to vulnerable populations.

Because all services covered by primary insurance are free at the point of service, medical expenditures in this system are financed primarily through general tax revenue, or in some provinces with small income-based premiums, which together cover 70% of healthcare expenditure. Private supplementary and replacement insurance make up for the remaining 30% of medical expenditure. Employment-based supplementary insurance is the status quo among large employers and tends to cover services such as optometry, dental, and extended prescription drug coverage.

In most provinces, there are no selective contracts, hence the consumers are not limited to any particular network of providers; however, gatekeepers are often used so that consumers must obtain referrals from their family physicians to see specialists. Office-based providers are paid fees for the services. Each province/territory sets its own fee schedule. Bundled DRG payments are used to allocate funds to hospitals in a few provinces (e.g., Ontario), but this system of payments is largely invisible to patients. Whereas providers are able to charge alternative fees, the provincial insurance programs will not pay for any of the services not charged at the regulated rates. This means a provider who does not accept the government’s rates must bill the patient, or the patient’s secondary insurance, for the full amount of the fee. The patient will not be reimbursed by the government’s insurance program for any out-of-pocket expenses. It is important to note under most provincial and territorial laws, private insurers are restricted from offering coverage for the services provided by the government’s program.

Although provider shortages and long wait times to receive services push costs down, Canada is also struggling to control rising healthcare costs. The elderly population is increasing in size and it is difficult to maintain the level of benefits Canadian citizens have become accustomed to; cutting covered services is causing frictions in the country.

Germany

The German government sponsors mandatory universal insurance coverage for everyone, including temporary workers residing in Germany. Germany’s primary insurance system is a social health insurance system that covers approximately 90% of the population in approximately 200 competing health plans (called Sickness Funds), with the remainder of the population (primarily high-income consumers) purchasing private replacement health insurance system. Although employers play a role in tracking plan enrollment, collecting revenue from employees and passing it along to a quasigovernment agency, they are not sponsors: Insurance is not employment based in that all plans are available without regard to where a consumer works. Germany spent approximately 12% of GDP on healthcare in 2009.

Germany’s health spending, excluding private insurers, is mostly funded by an income tax. This tax is a fixed portion of income, usually 10–15%, depending on age, that is the same no matter which health plan an individual is enrolled in, and is shared equally by the employee and employer. Health plans are required to accept all applicants and pay all valid claims. Health plans are free to set premiums but due to strong competition there is almost no variation in price. Germans stop having to pay any payroll tax for healthcare at the age of 65 years even while continuing to receive healthcare benefits. Patients are also expected to pay a quarterly copayment to their primary care doctor. Collection of payroll taxes and premiums is managed by employers, although employers play no role in defining choice options and merely pass along taxes and premiums to an independent government agency. Government subsidies are provided for the unemployed or those with low income. Risk adjustment is used to reallocate funds among the competing health plans, based on age, gender, and diagnoses.

In response to the acceleration of healthcare costs, Germany has implemented various cost-cutting measures. These include accelerating the transition to electronic medical records, introducing quarterly consumer payments to primary care doctors (although visits remain free). Nonprice rationing methods are also used; for example, in order to see a specialist, patients must first be diagnosed and receive a referral from a physician who acts as a gatekeeper. Selective contracting by health plans is allowed, but rare.

The German system uses a unique point-based global budgeting system to control annual healthcare expenditures, whereby the targeted expenditures are achieved by ensuring that total payments to all providers of a given specialty are equal to the total budget for that specialty in a year. The Federal Ministry of Health sets the fee schedule that determines the relative points for every procedure in the country. Each year the total spending on a specialty in a geographic area is divided by the number of procedure ‘points’ from specialists in that area to calculate the price per point, and each physician in that specialty is paid according to the number of accumulated points, up to quarterly and annual salary caps.

The primary insurance coverage offered through the funds is among the most extensive in Europe, and includes doctors, dentists, chiropractors, physical therapy, prescriptions, end-oflife care, health clubs, and even spa treatment if prescribed. There are also separate mandatory accident and long-term care insurance programs. A majority of consumers also purchase supplemental coverage from private insurers, and the supplemental coverage typically provides patients with dental insurance and access to private hospitals.

Japan

Japan has a mandatory insurance system that comprises an employment-based insurance for salaried employees, and a national health insurance for the uninsured, self-insured and low income, as well as a separate insurance program for the elderly. The employment-based insurance system is the primary insurance program in which employers play a significant role as sponsors and health plans have considerable flexibility in designing their benefit features. Employment-based insurance is of two kinds, distinguished between small and large firms. Health insurers offer employer-based health insurance that provides coverage for employees of companies with more than 5 but fewer than 300 workers and covers almost 30% of the population. Large employers (an additional 30% of the population) sponsor employee coverage through a set of society-managed plans organized by industry and occupation. Employer-based health insurance coverage must include the spouse and dependents. A public national health insurance program covers those not eligible for employer-based insurance, including farmers, self-employed individuals, the unemployed, retirees, and expectant mothers, who together comprise approximately 34% of the population. Health insurance for the elderly covers and provides additional benefits to the elderly and disabled individuals. Finally, any household below the poverty line determined by the government is eligible for welfare support. Altogether Japan spends approximately 9.3% of GDP on healthcare (2011).

Health insurance expenditures in Japan are financed by payroll taxes paid jointly by employers and employees as well as by income-based premiums paid by the self-employed. Fees paid to the healthcare workers and institutions are standardized nationwide by the government according to price lists. The largest share of healthcare financing in Japan is raised by means of compulsory premiums levied on individual subscribers and employers. Premiums vary by income and ability to pay.

Employers have little freedom to alter premium levels, which range from 5.8% to 9.5% of the wage base. Premium contributions are evenly split between employees and employers. Cost-sharing includes a 20% coinsurance for hospital costs and 30% coinsurance for outpatient care. Employerbased insurance is further subdivided into society-managed plans, government-managed plans, and mutual aid associations. Patients may choose their own general practitioners and specialists and have the freedom to visit the doctor whenever they feel they need care. There is no gatekeeper system.

All hospitals and physician’s offices are not-for-profit, although 80% of hospitals and 94% of physician’s offices are privately operated. Japan has a relatively low rate of hospital admissions, but once hospitalized, patients tend to spend comparatively long periods of time in the hospital, notwithstanding low hospital staffing ratios. In Japan, the average hospital stay is 36 nights compared to just 6 nights in the US. This high average is likely to reflect the inclusion of long-term care stays along with normal hospital stays in the average.

Health insurance benefits designed to provide basic medical care to everyone are similar. They include ambulatory and hospital care, extended care, most dental care, and prescription drugs. Not covered are such items as abortion, cosmetic surgery, most traditional medicine (including acupuncture), certain hospital amenities, some high-tech procedures, and childbirth. Expenses that fall outside the normal boundaries of medical care are either not covered, dealt with on a case-by-case basis, or covered by a separate welfare system.

United States

The US system is at its heart an employment-based health insurance system in which employers play a key role as sponsors of their employees. By one count, there are over 1200 private insurance companies offering health insurance in the US, which are regulated primarily by the 50 states and not at the federal level. These companies offer tens of thousands of distinct health insurance plans, each with their own premiums, lists of covered services, and cost-sharing features. In addition to this private system, there are also many overlapping public specialized insurance programs designed to cover consumers who are elderly, disabled, or suffering from end-stage renal disease (Medicare program), the poor or medically needy (Medicaid), children, veterans, and the self-employed. Because the US relies on both private and public insurance it is sometimes called a mixed insurance system. As of 2012, approximately 17% of the US population was without primary insurance, although many of these consumers are in fact eligible for Medicaid coverage but do not realize it. Altogether, the US spends nearly 18% of GDP on healthcare, the highest of any developed country.

Although the government acts as the sponsor to all of the public specialized insurance programs, employers are the key sponsor for most Americans. Choice is available to almost every agent in the US system: consumers choose providers, health plans, and sponsors; and employers, health plans and providers can generally turn down consumers who they prefer not to insure/employ, enroll, or provide services to. Employers generally contract with health plans while trying to control costs, but find little competition to hold down prices or control utilization. Many health plans negotiate fee reductions with provider groups, who tend to have substantial market power, but fees for medical care services in the US are with few exceptions the highest in the world. Although the US Medicare program sets provider fees for all regions without negotiation, all health plans must negotiate prices to be paid to providers, and the resulting fees reflect bilateral bargaining with market power.

The 2010 ACA dramatically changed many features of the US healthcare system and should greatly reduce the number of Americans who are uninsured. Starting in 2014 consumers who are without insurance will have to pay a tax penalty, and employers above a certain size will have to offer insurance to their full-time employees or pay a penalty. This US system also entails setting up insurance exchanges to cover the self-employed and small employers, who have the hardest time obtaining insurance in the US. The ACA does relatively little to address cost-containment issues, but does work toward expanding the number covered by insurance. It is unclear whether the national reform will work as well as it has in Massachusetts, where it has reduced the percentage that is uninsured to less than 2% of the population.

Cost containment is a huge issue in the US with such high spending in relation to its income. Demand-side cost sharing is used widely, with copayments, coinsurance, deductibles, coverage ceilings, and tiered payments all being used to deter demand. Many health plans use supply-side cost sharing, such as DRG bundled payments, and some are beginning to bundle primary care payment. Tiered provider payment, a form of ‘Value based Insurance,’ is also beginning to be used. Recent innovations include capitated provider networks, known as Accountable Care Organizations and reorganizing primary care providers to work and be paid as a Patient Centered Medical Home. Pay for performance systems and electronic medical records are other innovations being tested. It is too early to know which of these systems will be most successful in controlling costs.

Much can be written about the US public insurance programs – Medicare, Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, and The Department of Veterans Affairs – which also have their own payment systems and cost containment issues. The key point is that there is a huge amount innovation, from which other countries can learn. A positive feature of the US system is the exploration of diverse payment, nonprice, and informational programs to try to control costs. Individuallevel healthcare data is more available from the US than from any of the other four countries studied here. Also, consumer information about doctors, hospitals and health plans are all available and can potentially play a role in consumer choice.

With the exception of Singapore, the US healthcare system is arguably the most unfair healthcare system, with consumers who are poor or ill with chronic illnesses paying a high share of their income for medical care. Healthcare spending is a common source of individual bankruptcy.

Singapore

Singapore has a unique-to-the-world healthcare system where the dominant form of insurance is mandatory self-insurance supported by sponsored saving, although complementary and special insurance programs are also central to their system. Remarkably, despite having a per capita GDP of approximately US$60 000 in 2011, Singapore spent a mere 3–4% of GDP on healthcare (2012). The centerpiece of its system is a mandatory income-based individual savings program, known as Medisave, that requires consumers to contribute 6–9% (based on age and up to a maximum of US$41 000 per year) of their income to an HSA. This HSA can be spent on any healthcare services a consumer wishes, including plan premiums. Funds not spent in a consumer’s HSA can be carried forward to pay for future healthcare, used to pay for healthcare received by other relatives or friends, or if over the age of 65 years, cashed out to use as additional income, though there are some restrictions. A complementary insurance plan, known as Medishield, is available to cover a percentage of expenses arising from prolonged hospitalization or extended outpatient treatments for specified chronic illnesses, though it excludes consumers with congenital illnesses, severe preexisting conditions and those over the age of 85 years. As of 2011, this specialized program, which is optional, covered approximately 65% of the population. The government also supports a second catastrophic spending insurance program, known as Medifund, which exists to help consumers whose Medisave and Medishield are inadequate. The amount consumers can claim from this catastrophic insurance fund depends on their financial and social status. Singapore’s system also includes a privately available, optional insurance program covering longterm care services (called Eldershield), with fixed age of entry based payments. Consumers are automatically signed up for Eldershield once they reach the age of 40 years but they may opt out if they wish. Subsidies are available for most services, but even after the subsidies consumers must pay something out of pocket for practically all services. Some, but not all, subsidies depend on the consumer’s income, and consumers often have a choice over different levels of subsidy.

Funding for all three of the secondary insurance programs (Medishield, Medifund, and Eldershield) comes from general tax revenue. There are also five private insurance companies offering comparable plans, some of which are complementary to Medishield. Singapore has both public and private providers with the public sector providers serving the majority of inpatient, outpatient, and emergency care visits and the private sector serving the majority of primary and preventative care visits. Singapore’s system receives positive publicity for its low percentage of GDP spending on healthcare but has been criticized as not replicable elsewhere. The relatively small population and high GDP per capita allows Singaporeans to avoid some of the costs associated with regulating health insurance in larger, more populous countries. Perhaps Singapore’s most substantial criticism is insufficient coverage for postretirement healthcare expenses. Between potentially diminished savings and being cut off from Medishield at the age of 84 years, there is little support for financing catastrophic illnesses. Other criticisms of the country center on fairness concerns. The system favors high-income over low-income households, as they will have much greater funds contributed to their HSA. Also, consumers with high-cost chronic conditions, such as diabetes and mental illness, will repeatedly deplete their HSA and need to fall back on the various secondary insurance programs. Stigma is also an important cost containment mechanism. Finally, although consumers are incented to shop around among providers, as of 2012 there are no readily available report cards or other information sources available to guide consumers to lower cost or high-quality doctors and hospitals.

Concluding Thoughts

From the above descriptions, it is clear that there are an enormous number of ways that healthcare insurance programs vary around the world. Most country systems can be viewed as combinations or variations on the five systems described here. Although it would be wonderful if there were a way of identifying the characteristics of the most effective systems and the most equitable ones, unfortunately doing so in this article would require going beyond the boundaries of what is feasible. There are several excellent surveys of country healthcare systems, notably from the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development and a series by the Commonwealth Fund that are excellent and are worthy of References:.

References:

- Breyer, F., Bundorf, M. K. and Pauly, M. V. (2012). Health care spending risk, health insurance, and payments to health plans. In Pauly, M. V., McGuire, T. G. and Barros, P. P. (eds.) Handbook of health economics, vol. II. Amsterdam: Elsevier North-Holland.

- Busse, R., Schreyo¨gg, J. and Gericke, C. (2007). Analyzing changes in health financing arrangements in high-income countries: A comprehensive framework approach, health, nutrition and population (HNP). Discussion paper of The World Bank’s Human Development Network. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Cutler, D. M. and Zeckhauser, R. J. (2000). The anatomy of health insurance. In Cuyler, A. J. and Newhouse, J. P. (eds.) Handbook of health economics, vol. I, pp 563–637. Amsterdam: Elsevier North-Holland.

- Davis, K., Schoen, C. and Stremikis, K. (2010). Mirror, mirror on the wall: How the performance of the U.S. health care system compares internationally. New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund.

- Ellis, R. P. and Fernandez, J. G. (in press). Risk selection, risk adjustment and choice: Concepts and lessons from the Americas. Boston, MA: Boston University.

- European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2013) Health systems in transition (HIT) series. Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/en/who-we-are/ partners/observatory/health-systems-in-transition-hit-series (accessed 15.04.13).

- Henke, K.-D. and Schreyo¨gg, J. (2004). Towards sustainable health care systems – strategies in health insurance schemes in France, Germany, Japan and The Netherlands. Geneva: International Social Security Association.

- McGuire, T. G. (2012). Demand for health insurance. In Pauly, M. V., McGuire, T. G. and Barros, P. P. (eds.) Handbook of health economics, vol. II. Amsterdam: Elsevier North-Holland.

- Meulen, R. T. and Jotterand, F. (2008). Individual responsibility and solidarity in European health care. Journal of Medicine and Philosophy 33, 191–197.

- Physicians for a National Health Program (2013) International Health Systems. Available at: http://www.pnhp.org/facts/international_health_systems.phppage=all (accessed 15.04.13).

- Rice, N. and Smith, P. C. (2001). Ethics and geographical equity in health care. Journal of Medical Ethics 27, 256–261.

- Saltman, R. B., Busse, R. and Figueras, J. (2004). Social health insurance systems in Western Europe. Berkshire: Open University Press.

- Thomson, S. and Mossialos, E. (2010). Primary care and prescription drugs: Coverage, cost-sharing, and financial protection in six European countries. New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund.

- Thomson, S., Osborn, R., Squires, D. and Reed, S. J. (2011). International profiles of health care systems. New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund.

- Van de Ven, W. P. M. M., Beck, K., Buchner, F., et al. (2003). Risk adjustment and risk selection on the sickness fund insurance market in five European countries. Health Policy 65, 75–98.

- Van de Ven, W. P. M. M. and Ellis, R. P. (2000). Risk adjustment in competitive health plan markets. In Culyer, A. J. and Newhouse, J. P. (eds.) Handbook of health economics, vol. I, pp 755–845. Amsterdam: Elsevier North-Holland.

- http://www.syndicateofhospitals.org.lb/magazine/jun2011/english/ Health%20System.pdf Syndicate of Hospitals.

- http://www.ciss.org.mx/pdf/en/studies/CISS-WP-05122.pdf The Inter-American Conference on Social Security.

- http://www.kaiseredu.org/Issue-Modules/International-Health-Systems/Japan.aspx The Kaiser Family Foundation.