Decision making is a fact of life, both for individuals and for policy makers acting on behalf of society. All decisions result in costs and benefits. The purpose of economic evaluation is to compare these and determine whether the costs of a policy are justified by the benefits.

Economic evaluations comprise two steps. First, a specific intervention is identified (e.g., a vaccination program), along with any relevant alternative uses of the same resources (e.g., other public health activities). The most desirable of these alternatives is referred to as the opportunity cost, since it represents the opportunity forgone by implementing the intervention. Second, the intervention and its opportunity cost are each assigned a value. The intervention is considered desirable only if it has greater value than its opportunity cost.

The opportunity cost of an intervention is usually dependent upon the point in time at which the costs of the intervention are incurred. For example, a rational decision maker would prefer to incur a cost of $100 next year rather than a cost of $100 this year, if this allows the $100 to be invested for an year and yield a positive return.

Meanwhile, the value assigned to the benefits of the intervention and its opportunity cost generally depends upon the point in time at which these benefits will be experienced. For example, the benefits from a vaccination program due to be experienced 10 years from now may be assigned less value by the policy maker than the benefits realized from an alternative health intervention this year, even if these benefits are otherwise identical. This is known as time preference.

To allow for comparability between costs and benefits experienced across different points in time, it is conventional to represent all future costs and benefits in terms of their present value (i.e., their value today), regardless of when they are actually experienced. Typically, the present value of future costs and benefits is less than their value at the time they are experienced. Calculating present values therefore requires discounting of future costs and benefits. Although in everyday language the term ‘discounting’ is used in a variety of contexts, in economics it is used almost exclusively to describe the steps taken to calculate the present value of future costs and benefits.

Discounting is conducted as follows. First the costs and benefits are disaggregated into time periods (usually years). Then the costs and benefits in each time period are assigned weights, with lower weights assigned to more distant time periods. These weights are usually given by

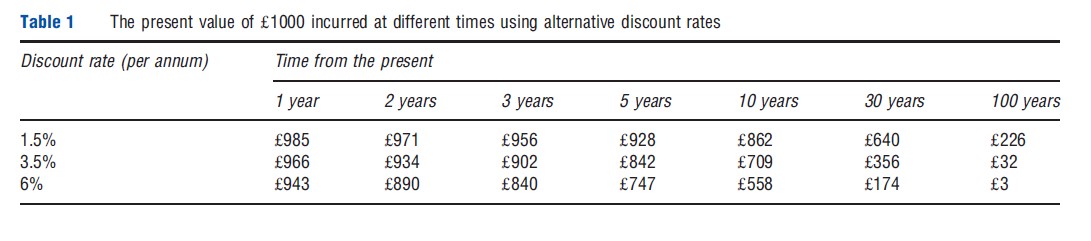

where t represents the time period and d represents the discount rate. Costs and benefits incurred in the current time period (t=1) are not discounted. As a result of compounding, the discount applied to costs and benefits in the distant future can be substantial. For example, since 2003 the UK Treasury has recommended that most future costs and benefits be discounted at an annual rate of 3.5%. This means that a cost of ₤1000 incurred 30 years from now has a present value of ₤356 [1000/(1+0.035)29]. Before 2003, the UK Treasury recommended a higher discount rate of 6%, which would have resulted in a present value of just ₤174 [1000/(1+0.06)29]. The effect of this compounding is demonstrated in Table 1.

In some cases there are further complications to consider. First, costs and benefits might not be discounted at the same rate. For example, the Dutch Health Care Insurance Board recommends discounting costs at 4% per year and benefits at 1.5% per year. This practice is known as differential discounting, and has recently been the subject of considerable debate. Second, the discount rate itself might be conditional upon the point in time at which costs and benefits occur. For example, the UK Treasury recommends that a lower discount rate be applied to costs and benefits more than 30 years in the future, with this rate falling progressively from 3.5% at 30 years to 1.0% beyond 300 years. This is known as nonconstant discounting, of which hyperbolic discounting is a common form.

Discounting can tip the balance between an intervention appearing desirable or not. It can also impact upon the relative desirability of interventions. Interventions with upfront costs but long term benefits (including many public health activities) generally appear less desirable following discounting, whereas interventions with long-term costs sometimes appear more desirable.

Given the complexities of discounting and its potential importance, it is the subject of considerable controversy. In the following article, the rationales for discounting are explained in greater detail. Some of the more contentious issues in discounting, such as the merits of differential or non-constant discounting, are discussed. Recent papers that have attempted to determine the appropriate discount rates for health policy making are then reviewed. The article ends with some suggested further reading.

Conventional Approaches To Discounting

Discounting is founded on considerations of opportunity cost and time preference. A common way of considering the opportunity cost of an intervention is to estimate the ‘marginal social opportunity cost of capital,’ which represents the amount of private investment foregone by adopting the intervention. Meanwhile, time preference is often considered by estimating the ‘social rate of time preference,’ which represents society’s time preference for consumption.

Opportunity Cost

In cases where the resources used for a publicly funded intervention can otherwise be used in the private sector, the opportunity cost of the intervention is the value of the best possible forgone private investment opportunity. In this case, the intervention should only be funded if its benefits exceed those of the forgone private investment. In technical terms, this requires that the rate of return on the intervention exceeds the marginal pretax rate of return on the forgone private investment, otherwise known as the marginal social opportunity cost of capital.

Many economists have proposed methods for estimating the marginal social opportunity cost of capital. Under strict assumptions, it is equivalent to the marginal pretax rate of return on riskless private investments. This is sometimes approximated by the average real pretax rate of return on toprated corporate bonds. However, this may be an over-estimate if the average rate of return is higher than the marginal rate of return, or if market distortions affect the rate of return.

Time Preference

It has been widely observed that individuals exhibit time preference: they prefer to receive benefits sooner rather than later. Economists have three standard explanations for individual time preference, each of which may be extended to explain time preference at the level of society.

Individual Time Preference

The first explanation for individual time preference is that individuals may expect their incomes to increase over time, allowing them to consume more in the future than they do today. However, the extra utility that individuals receive from any additional consumption tends to decline as consumption increases. As a result, individuals may prefer to consume more today, at the expense of future consumption, in order to smooth their lifetime consumption and increase their lifetime utility.

Second, every individual faces some risk of death or some other catastrophe that would prevent them from consuming in the future. Offered the choice between consumption today and identical consumption in 30 years’ time, many individuals would prefer to consume today on the grounds that they are not guaranteed to be alive for 30 years’ time.

Third, individuals might prefer to consume sooner rather than later regardless of their expectations of future consumption. This is referred to as pure time preference, and reflects the fact that individuals often exhibit myopic or impatient preferences. Individuals might not appreciate that they are forfeiting future consumption by consuming more sooner, or they might regard their future utility as being less important than their utility today.

Societal Time Preference

Extending the first explanation for individual time preference to the societal level is relatively uncontroversial. As the incomes of individuals increase over time, the aggregate consumption of society also increases. Policy makers, acting on behalf of society, may prefer to enact policies which not only smooth the consumption of individuals over their lifetimes but also smooth the aggregate consumption of society over time, so as to maximize aggregate utility (i.e., social welfare) across generations.

Extending the second explanation to the societal level is more problematic. Although individuals face a non-negligible risk of an event, such as death, which prevents them from consuming in future years, the risk of catastrophe faced by society is much smaller. Although every year some members of society will die (or emigrate), others will be born (or immigrate) and society can be expected to carry on regardless. Only a truly catastrophic event would prevent society from consuming in future years. Consequently, society has much less justification than individuals for preferring consumption sooner rather than later.

The final explanation for individual time preference – that individuals often have myopic or impatient preferences – is particularly controversial in a societal context. Although there is considerable empirical evidence that individuals exhibit these preferences, many economists, philosophers, and other thinkers have argued against considering these pure time preferences in societal decision making. This is discussed further in the next section.

The social rate of time preference represents the rate at which society is willing to postpone current consumption in exchange for future consumption.

Under strict assumptions this may be approximated by the after-tax rate of return on risk-free securities (e.g., government bonds). However, these assumptions require that individuals express all their preferences within the market. In addition, the approximation presupposes that individuals do not change preferences when faced with decisions that affect society rather than just themselves. Where these assumptions do not hold, the social rate of time preference is likely to be lower than that implied by market rates.

An alternative means of estimating the social rate of time preference is to use a formula attributed to British mathematician Frank Ramsey. According to the Ramsey formula, the social rate of time preference is given by

The formula assigns a separate rate to each of the three standard explanations for time preference given above – the diminishing marginal utility of consumption (mg), the risk of a catastrophic event (L), and pure time preference (d) – and sums these to give the social rate of time preference. The rate assigned to the diminishing marginal utility of consumption is calculated by multiplying an estimate of the elasticity of the marginal utility of consumption (m) by the growth rate of real per capita consumption (g). The UK Treasury used this methodology in 2003 to derive its current 3.5% discount rate: citing various sources, it estimated that μ=1, g=2%, L=1%, and δ= 0.5%, implying a social rate of time preference of 3.5% per annum.

Deriving A Social Discount Rate

Conventionally, attempts to derive a social discount rate – used to discount future costs and benefits in economic evaluations of public interventions – have focused on reconciling the marginal social opportunity cost of capital with the social rate of time preference. Under very unrealistic assumptions, including complete and undistorted markets, the marginal rate at which present consumption opportunities can be transformed into future consumption opportunities is equal to the marginal rate at which society would choose to substitute present for future consumption. Under such a scenario the marginal social opportunity cost of capital and the social rate of time preference are equivalent. Where these assumptions do not hold, some economists have advocated using one or the other as the social discount rate, whereas others have proposed ways of reconciling the two. These include the ‘weighted average’ and the ‘shadow price of capital’ approaches.

The weighted average approach holds that the social discount rate should be a weighted average of the marginal social opportunity cost of capital, the social rate of time preference, and, in the case of an open economy, the cost of borrowing on international markets. These weights should reflect the proportion of funds obtained from each source, implying a different social discount rate for each intervention. A limitation of the weighted average approach is that the benefits of the intervention are assumed to be consumed immediately. If these benefits are instead reinvested in the private sector, the weighted average approach will overestimate the social discount rate.

The shadow price of capital approach addresses a key limitation of the weighted average approach by recognizing that the benefits of an intervention may be reinvested in the private sector. The benefit of an intervention is given by the sum of the consumption resulting from the intervention and any future consumption generated from reinvestment of the benefit. The cost is given by the sum of the consumption directly displaced by the intervention and any future consumption forgone because of the displacement of private investment. Although this approach is theoretically attractive, it is more difficult to implement than the weighted average approach.

Discounting In The Context Of Health Policy Making

Conventional approaches to deriving a social discount rate can be problematic in the context of health policy making. Health policy makers are often faced with a constrained budget. In this context, the opportunity cost of adopting a specific health intervention is typically not forgone private investment, but rather displaced health care activities elsewhere within the health care system. Furthermore, health policy makers are often concerned specifically with society’s health, rather than society’s consumption. Since society’s time preferences for health typically differ from those for consumption, health policy makers may therefore need to instead consider the ‘social rate of time preference for health.’ Finally, health policy makers may have reason to adopt different discount rates for costs and health benefits, rather than a single ‘social discount rate’ for both (this is returned to in the final section). For clarity, the ‘social rate of time preference’ will hereafter be referred to as the ‘social rate of time preference for consumption,’ to differentiate it from the ‘social rate of time preference for health.’

The Social Rate Of Time Preference For Health

The standard explanations for society’s time preference for consumption also apply to society’s time preference for health. As society’s health improves over time, it may have a preference for earlier health benefits over later health benefits, because of the diminishing marginal utility of health. Society may also prefer earlier health benefits because of catastrophe risk or pure time preference.

The social rate of time preference for health generally differs from the social rate of time preference for consumption. One reason is that the relative value of health and consumption might change over time. Dave Smith and Hugh Gravelle have suggested that the consumption value of health might grow over time, since it is positively correlated with increasing incomes.

The social rate of time preference for health may be estimated using the Ramsey formula. It may also be implicitly revealed by the allocation of health budgets across time (this is returned to in the final section).

Implications For Discounting

Where a health policy maker has a specific concern for society’s health, and is faced with a fixed budget constraint, it follows that the appropriate discount rate(s) to adopt for economic evaluations of health interventions cannot be derived from either the marginal social opportunity cost of capital or the social rate of time preference for consumption, but rather by considering the social rate of time preference for health and the specific opportunity cost of adopting the health intervention in question (i.e., the health forgone elsewhere as a result of displaced health care activities). The final section of this article reviews recent work demonstrating how the discount rate(s) should be derived in this context.

Contentious Issues In Discounting

Should Benefits Be Discounted At All?

Although there is substantial empirical evidence that individuals prefer earlier benefits to later benefits, there is widespread controversy over whether society should display similar time preferences. Some authors have expressed frustration that discounting health benefits causes many interventions (particularly public health activities) to appear much less desirable. Others have raised ethical objections on the grounds that discounting benefits discriminates against future generations.

A popular view among contemporary economists is that social welfare should be determined by aggregating the preferences of individuals, specifically those individuals who are members of the currently living generation. It follows that if these individuals prefer earlier benefits to later benefits then society should too. An exception is sometimes made for those aspects of individual time preference resulting from myopia or impatience. Many economists regard economic evaluation as a means of bringing greater rationality into societal decision making, and so oppose the consideration of these aspects of time preference on the basis that they are ‘irrational.’ This view is not universally shared by economists. For example, the UK Treasury explicitly considered such preferences in the derivation of its 3.5% discount rate.

This focus on the preferences of individuals is a relatively new concept. As Murray Krahn and Amiram Gafni have noted, earlier thinkers, including Jeremy Bentham, David Hume and the early utilitarians, had an objective, interpersonal and intergenerational view of social welfare, in which the subjective preferences of the current generation were given relatively little weight. The time preferences of individuals were viewed as a failing of human reason, as representing intellectual or moral weakness, and potentially harmful to social welfare. According to Arthur Cecil Pigou, the government therefore has a ‘duty’ to ‘‘protect the interests of the future in some degree against the effects of our irrational discounting and of our preference for ourselves over our descendants.’’ More recently, John Rawls argued that the principle of intergenerational justice should guide social decision making, in which the interests of all generations are given equal consideration.

However, there are legitimate reasons for individuals and society to prefer earlier benefits, even if equal regard is given to the welfare of future generations. First, consumption or health may be expected to increase over time. If social welfare is regarded as an aggregation of individual utilities, and if there is diminishing marginal utility to consumption or health, then an equal concern for the welfare of all generations may require that preference be given to improving the consumption or health of earlier generations. Alternatively, if intergenerational justice requires that consumption or health be equalized across generations, then an expectation that consumption or health will increase over time implies that preference should be given to improving the consumption or health of earlier generations. Finally, there is always some risk, however small, of a catastrophe preventing society from enjoying the benefits of consumption or health in the future.

It follows that society’s rate of time preference for either consumption or health is most likely positive but lower than that for individuals. For these reasons, future benefits generally should be discounted, regardless of whether society accounts for myopic or impatient preferences in societal decision making.

Should Costs And Health Benefits Be Discounted At Different Rates?

Although not a new controversy, this debate was reignited in 2004 by the decision of the UK’s National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) to no longer recommend the differential discounting of incremental costs and health benefits (at rates of 6% and 1.5% respectively) but instead recommend that both be discounted at a common rate of 3.5%. In a 2011 paper, Karl Claxton and colleagues brought together the prominent authors from both sides of this debate and clarified the causes of this disagreement.

The authors identified a number of matters of context which must be considered before this question can be answered, including the health policy maker’s perspective on social choice, the specific objective adopted by the policy maker, and whether the policy maker faces a fixed budget constraint.

Where the policy maker faces a fixed budget constraint, differential discounting is justified only if the cost–effectiveness threshold is expected to change over time. Alternatively, if the policy maker does not face a budget constraint, and if the policy maker adopts a welfarist or extra-welfarist perspective on social choice, then differential discounting is only justified if the consumption value of health is expected to change over time.

These issues are described in more detail in the next section.

Is Differential Discounting Logically Inconsistent?

A number of arguments have been made that differential discounting is logically inconsistent, and so common discounting is unavoidable. These include Emmett Keeler and Shan Cretin’s paradox of indefinite delay, Milton Weinstein and William Stason’s chain of logic argument, and William Kip Viscusi’s equivalence argument. Karl Claxton and colleagues also criticized the ‘illogicality’ of differential discounting in a previous paper in the recent debate. In response, Erik Nord has recently argued that all of these ‘consistency arguments’ are themselves logically inconsistent.

The Paradox Of Indefinite Delay

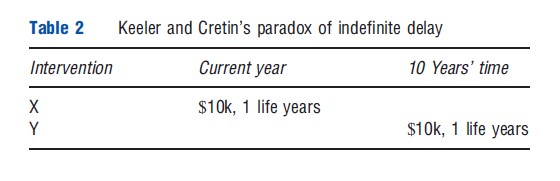

According to Keeler and Cretin’s paradox of indefinite delay, if two alternative interventions, X and Y, are identical in every respect, except that X is implemented today and Y is implemented in 10 years’ time (Table 2), then discounting benefits at a lower rate than costs will result in Y having a more favorable cost–benefit ratio than X. Unless benefits are discounted at a rate at least as high as costs, this implies that policy makers will always prefer to indefinitely delay every intervention.

A problem with this argument, as noted by Michael Parsonage and Henry Neuburger, is that the policy relevant question is not where in time to locate an intervention, but rather how to set priorities within a constrained budget in any given year. There is no reason to discount Y to today’s present value at all: it can simply be appraised in 10 years’ time, when it will have the same cost–benefit ratio as X. Nord argues that a distinction should also be made between start time difference and benefit time difference: policy makers may not wish to indefinitely postpone the start time of an intervention, but they may still have a preference over the timing of benefits in programs with given start times.

The Chain Of Logic Argument

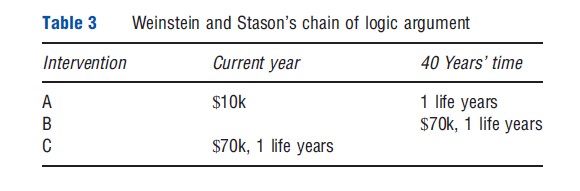

Weinstein and Stason’s chain of logic argument, cited by the Washington Panel as the ‘consistency argument,’ runs as follows. Suppose there are two interventions: A costs $10 000 now and saves 1 life year in 40 years’ time, while B costs $70 000 in 40 years’ time and also saves 1 life year in 40 years’ time. Assuming a discount rate on costs of 5%, A and B are equivalent. A third intervention, C, is then considered which costs $70 000 now and saves 1 life year now (Table 3). Assuming a constant value of a life year, C is equivalent to B and hence equivalent to A. Since C costs seven times as much as A, the benefits of C must also be seven times the value of those of A, implying a discount rate on benefits of 5%. Costs and benefits must therefore be discounted at the same rate.

However, Nord argues that this is true only if the value of a life year is constant, which was presupposed in the argument. Indeed, Weinstein and Stason acknowledged that adopting a non-constant value of a life year may justify differential discounting of costs and benefits.

The Equivalence Argument

Viscusi’s equivalence argument considers an intervention that costs $8 million now and saves two lives in 10 years. The value of a life in year 10 is V. Costs are discounted at r and benefits at d. In present value terms, the intervention is worthwhile if 2V/(1+d)10>8. Viscusi suggested that one could instead look at ‘terminal values,’ with the intervention worthwhile if 2V>8(1+r)10, which can be rearranged to 2V/(1+r)10>8. Since these equations are equivalent only if d=r, it follows that costs and benefits should be discounted at the same rate.

However, as Nord notes, Viscusi made only the trivial arithmetic point that if one uses the same discount rate for both costs and benefits then either present values or terminal values may be used. Viscusi presupposed d = r in his argument. The real issue about whether the discount rates should be the same is not addressed.

Further arguments

An earlier paper by Claxton and colleagues made two further arguments against the ‘illogicality’ of differential discounting: first, that support for differential discounting ‘‘must rest on a claim that health, unlike wealth, is not tradable over time’’; second, that ‘‘the true cost of health gained is health forgone – at whatever date these gains or losses may occur. Put in this fashion, the illogicality of wanting to discount health forgone at a different rate from health gained becomes plain.’’

The first argument is disputed by Nord, who notes that differential discounting can be justified even if health is tradable over time. The second argument is correct in stating that, faced with a fixed health budget constraint, ‘‘the true cost of health gained is health forgone,’’ but does not account for the possibility that the cost–effectiveness threshold might change over time. This possibility was considered in the more recent paper by Claxton and colleagues.

Is Non-Constant Discounting Appropriate?

Conventional discounting is consistent with Paul Samuelson’s discounted utility model, with a key assumption being that the discount rate remains constant over time. For example, if the discount rate is 5% then a benefit today is equivalent to a 5% greater benefit in 1 year, whereas a benefit in 10 years is equivalent to a 5% greater benefit in 11 years. Adopting a constant discount rate results in time consistent decision making. This means that if an intervention with distant costs and benefits appears worthwhile today, then it will also appear worthwhile if reappraised in 10 years’ time.

However, empirical studies have demonstrated that individuals rarely have a constant rate of time preference. Individuals often exhibit strong time preferences for benefits in the near future: offered a choice between $10 now or $15 next year, many will prefer $10 now. But this time preference becomes weaker in the distant future: offered a choice between $10 in 20 years’ time or $15 in 21 years’ time, many of these same individuals will prefer $15 in 21 years. A possible reason is that individuals have difficulty comprehending differences between distant time periods. The result is time inconsistent decision making: although the option of $15 in 21 years appears more attractive today, if asked to reappraise their decision 20 years from now many individuals will regret their decision and, if possible, switch their choice.

The issue of how to deal with time inconsistent decision making remains unresolved. Perhaps as a result, non-constant discounting (including hyperbolic discounting) is rarely adopted in practice. Although constant discounting allows policy makers to avoid this issue, the tradeoff is that society’s time preferences: cannot be fully reflected. An exception is the UK Treasury, which recommends non-constant discounting for very distant costs and benefits. The discount rate falls progressively from 3.0% (between 30 and 75 years), to 2.5% (76–125 years), to 2.0% (126–200 years), to 1.5% (201–300 years), to 1.0% (beyond 300 years). Even with this declining rate, costs and benefits in 300 years are given just 0.14% of the weight of present costs and benefits (under a constant discount rate of 3.5%, this weight would be 0.003%).

Discounting In The Context Of Health Policy Making

Over recent years, health policy makers around the world have made increasing use of cost–effectiveness analysis (CEA) to guide their decision making around the adoption of new health interventions. Typically a CEA compares the costs and health outcomes associated with a health intervention to each of its comparators, and a judgment made as to whether its adoption would be cost-effective. Policy makers, or the agencies which conduct CEAs on their behalf, generally publish guidance as to the discount rates that should be used. For example, NICE currently specifies that costs and health benefits should both be discounted at 3.5% per year, whereas the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology in Health (CADTH) recommends that both be discounted at 5% per year. Such guidance has the advantage of providing consistency and comparability across the variety of CEAs considered by each policy maker. It has also resulted in considerable debate as to the most appropriate discount rates to use, with much of this debate focused on the merits of differential discounting of costs and health benefits.

Recent contributions to this debate have demonstrated that the appropriate discount rates to use depend on the context in which health policy is made. This requires consideration of a number of issues, including the health policy maker’s perspective on social choice, the specific objective adopted by the policy maker, and the existence or otherwise of a fixed budget constraint for health.

The Perspective On Social Choice

In defining the policy context, the first consideration is the perspective on social choice adopted by the health policy maker. This is the subject of a vast literature, and there are many possible perspectives that policy makers may reasonably adopt. These can be usefully characterized into two groups: those that regard the primary purpose of policy making to be to improve social welfare, as defined by welfarist or extra-welfarist economics; and those that regard policy making as a means for satisfying specific and explicit objectives, rather than improving social welfare more generally.

A Welfarist Perspective

Traditional welfarist economics assumes that individuals rationally maximize their utility by ordering the various options available to them and acting according to their preferences. Individuals are regarded as the only judges of what contributes most to their utility. Social welfare is judged to be nothing more than an aggregation of these individual utilities. This notion of social welfare is very restrictive: in particular, it cannot take account of outcomes other than utilities, and it does not permit the use of sources of valuation other than the individuals affected by the policy decision.

An Extra-Welfarist Perspective

Over recent decades, these limitations have resulted in the rise of extra-welfarist economics, in which non-utility information such as the quality of individuals’ utilities, equity weights, and individuals’ characteristics and capabilities are considered alongside individual utilities. This provides substantially more flexibility in the definition of social welfare. Extra-welfarist economics otherwise retains many of the features of welfarist economics: the purpose of policy making is still to improve social welfare, and individual preferences remain an important consideration.

Problems With The Definition Of Social Welfare

To judge whether policy decisions improve social welfare requires the expression of an explicit and complete social welfare function: a ranking over all conceivable social states. However, there are many reasons why the expression of an explicit and complete social welfare function might not be possible or even desirable. The work of Nobel Laureates Kenneth Arrow and Amartya Sen demonstrated that it is impossible to specify an explicit and complete social welfare function that satisfies basic requirements while remaining non-dictatorial and respecting minimal liberty. It is therefore unlikely that any explicit and complete social welfare function could be expressed which would carry social legitimacy. Furthermore, policy makers may express no desire in specifying an explicit social welfare function in any case. This is problematic if improving social welfare is regarded as the primary purpose of policy making.

A Social Decision-Making Perspective

In response, many economists have advocated for an alternative approach. The social decision-making perspective identifies a more modest role for policy making: satisfying specific and explicit objectives rather than improving social welfare more generally. Under this perspective, policy making agencies (such as NICE) are seen as agents of a socially legitimate higher authority (in NICE’s case the UK’s democratically elected parliament). This higher authority does not specify an explicit social welfare function, but nevertheless allocates resources among different sectors (e.g., health, education, etc.) and grants each agent the responsibility to pursue a specific and explicit objective subject to a budget constraint. In NICE’s case, this objective may be to improve society’s health, subject to the budget for health allocated by the UK parliament. Although the higher authority does not specify an explicit social welfare function, the objectives it delegates to the agents, and its allocation of resources between sectors and within sectors across time, represent a partial expression of some unknown latent social welfare function.

The Objective Of The Policy Maker

The second consideration of context is the health policy maker’s objective. This is influenced by the perspective on social choice. A recent paper by Karl Claxton and colleagues considers two possible objectives that a health policy maker might reasonably adopt: the first under a social decision-making perspective, the second under a welfarist or extrawelfarist perspective.

A Social Decision-Making Perspective

Under a social decision-making perspective, the health policy maker may reasonably seek to improve society’s health, subject to the budget constraint set by the higher authority. Society may also have a preference for earlier health benefits, represented by the social rate of time preference for health. The health policy maker’s objective may therefore be to ‘maximize the present value of health.’

A Welfarist Or Extra-Welfarist Perspective

Under a welfarist or extra-welfarist perspective, the health policy maker instead seeks to improve social welfare. Health may be considered in consumption terms by weighting it by the consumption value of health. As Hugh Gravelle and colleagues note, if consumption and health are the only arguments in the social welfare function, or are separable from other arguments, then maximizing the consumption value of health is equivalent to maximizing social welfare. Society’s time preferences are represented by the social rate of time preference for consumption. The health policy maker’s objective may therefore be to ‘maximize the present consumption value of health.’

The Existence Or Otherwise Of A Budget Constraint

The third consideration of context is the existence or otherwise of a fixed budget constraint for health. This has important implications for the opportunity cost of adopting an intervention.

A Constrained Budget

Where the health budget is constrained, any additional costs of adopting an intervention fall within this budget. It is inevitable that one or more other health interventions will then be displaced, resulting in forgone health. This represents the opportunity cost of adopting the intervention. A critical part of appraising the cost–effectiveness of the intervention is estimating this opportunity cost. Unfortunately, health policy makers are usually unaware of the specific health interventions displaced, so the extent of forgone health must be estimated in some other way.

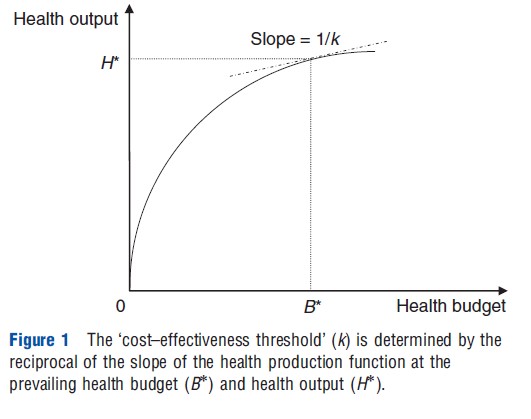

One such approach is to estimate the slope of the health production function. This function describes how changes in the health budget affect the aggregate health output of the health system, with health output usually considered to be a positive but diminishing function of the health budget. The reciprocal of the slope of the health production function at the prevailing health budget and health output represents the ‘cost–effectiveness threshold,’ denoted as k in Figure 1.

The cost–effectiveness threshold reveals how much health output is expected to be forgone following a marginal reduction in the existing health budget. For example, suppose that reducing the health budget by $50 000 reduces aggregate health output by 1 quality-adjusted life-year (QALY). The expected opportunity cost of adopting a new intervention would therefore be 1 QALY for every additional $50 000 spent, implying a cost–effectiveness threshold of $50 000 per QALY.

Since the cost–effectiveness threshold represents a matter of fact – how much health output is forgone, rather than the value of this health output – its estimation is an empirical matter. All else equal, the cost–effectiveness threshold will grow with increases in the health budget and fall with improvements in the marginal productivity of the health system. The possibility of the cost–effectiveness threshold changing over time must therefore be considered by health policy makers.

A Non-Constrained Budget

Where the health budget is not constrained, any additional costs associated with adopting an intervention generally fall on other sectors or taxpayers. Under a welfarist or extrawelfarist perspective, the resulting opportunity cost may be regarded in terms of forgone consumption. To determine the cost–effectiveness of the intervention, the health benefits can be weighted by the consumption value of health so that a comparison may be made in consumption terms. Since adopting interventions in this context does not displace health, the cost–effectiveness threshold is redundant.

The Appropriate Discount Rates To Adopt

Recent work by Karl Claxton and colleagues demonstrated how these matters of context determine the appropriate discount rates for the health policy maker to adopt when appraising the cost–effectiveness of health interventions.

In cases where the health policy maker is faced with a constrained health budget, the authors assume that the policy maker determines whether an intervention is cost-effective by comparing its incremental cost–effectiveness ratio (ICER) to the current estimate of the cost–effectiveness threshold. Alternatively, where the health budget is not constrained, it is assumed that this ICER is compared to the current estimate of the consumption value of health.

According to Claxton and colleagues, where the health budget is constrained and the policy maker adopts a social decision-making perspective on social choice:

- Incremental costs should be discounted at approximately the social rate of time preference for health plus the expected growth rate of the cost–effectiveness threshold.

- Incremental health benefits should be discounted at the social rate of time preference for health.

Alternatively, where the health policy maker adopts a welfarist or extra-welfarist perspective:

- If the health budget is constrained, incremental costs should be discounted at approximately the social rate of time preference for consumption minus the expected growth rate of the consumption value of health plus the expected growth rate of the cost–effectiveness threshold.

- If the health budget is not constrained, incremental costs should be discounted at the social rate of time preference for consumption.

- Regardless of whether or not the health budget is constrained, incremental health benefits should be discounted at approximately the social rate of time preference for consumption minus the expected growth rate of the consumption value of health.

In a subsequent paper, Mike Paulden and Karl Claxton provide an alternative specification for the appropriate discount rates to adopt under a social decision-making perspective. The authors argue that, in societies with a single-payer health system funded by a socially legitimate higher authority (such as a democratically elected parliament), the social rate of time preference for health is implicitly revealed by the allocation of health budgets across time. In this context, the social rate of time preference for health is shown to be approximately equal to the real interest rate faced by the higher authority which finances the health system minus the expected growth rate of the cost–effectiveness threshold.

Combining this result with the findings of Claxton and colleagues, it follows that:

- Incremental costs should be discounted at the real interest rate faced by the higher authority which finances the health system.

- Incremental health benefits should be discounted at approximately the real interest rate faced by the higher authority that finances the health system minus the expected growth rate of the cost–effectiveness threshold.

Intuition And Policy Implications

Where the budget is constrained, expected growth in the cost–effectiveness threshold must be accounted for, since the opportunity cost of adopting interventions also changes (for higher thresholds, incremental costs result in less health forgone, and vice versa). However, when the ICER of the intervention is compared to the current estimate of the cost–effectiveness threshold, this growth is not accounted for. The only practical way to account for this growth is to adjust the discount rate used for incremental costs. This results in differential discounting.

Under a welfarist or extra-welfarist perspective, if the consumption value of health is expected to change over time, an adjustment must be applied to the discount rate for incremental health benefits. If the health budget is not constrained, this results in differential discounting. However, if the health budget is constrained, the same adjustment must also be made to the discount rate used for incremental costs. This is because incremental costs fall on the health budget and result in forgone health, and any change in the consumption value of health also applies to health forgone. Under a constrained budget, change in the consumption value of health does not therefore justify differential discounting, but rather a lower discount rate for both incremental costs and health benefits. In this case, differential discounting is only appropriate if the cost–effectiveness threshold is expected to change over time.

Estimating the growth rate of the cost–effectiveness threshold requires extensive empirical research. With the exception of recent work in the UK, this research has not yet been undertaken in any jurisdiction. Theoretically, the cost–effectiveness threshold should grow with increases in the health budget but shrink with improvements in marginal productivity. As such, it may not be obvious in many jurisdictions whether the cost–effectiveness threshold is growing or shrinking. As Mike Paulden and Karl Claxton note, it may therefore be reasonable to assume that the growth rate of the cost–effectiveness threshold is zero (implying common discounting of incremental costs and health benefits) until a reliable empirical estimate of the growth rate of the cost–effectiveness threshold is available.

The real interest rate faced by a higher authority may be approximated by the real yield on its long term bonds. As of November 2012, the real yield on long term bonds issued by the UK and Canadian governments was in the region of 0.5–1.5% per annum. It follows that, under a social decision-making perspective, health policy making agencies such as NICE and CADTH should discount incremental costs and health benefits at a lower common rate than currently recommended.

References:

- Brouwer, W., Niessen, L., Postma, M. and Rutten, F. (2005). Need for differential discounting of costs and health effects in cost effectiveness analyses. British Medical Journal 331(7514), 446–448.

- Brouwer, W., Culyer, A., Van Exel, N. and Rutten, F. (2008). Welfarism vs. extrawelfarism. Journal of Health Economics 27(2), 325–338.

- Claxton, K., Paulden, M., Gravelle, H., Brouwer, W. and Culyer, A. (2011). Discounting and decision making in the economic evaluation of health-care technologies. Health Economics 20(1), 2–15.

- Claxton, K., Sculpher, M., Culyer, A., et al. (2006). Discounting and cost–effectiveness in NICE – Stepping back to sort out a confusion. Health Economics 15(1), 1–4.

- Frederick, S., Loewenstein, G. and O’Donoghue, T. (2002). Time discounting and time preference: A critical review. Journal of Economic Literature 40(2), 351–401.

- Gravelle, H., Brouwer, W., Niessen, L., Postma, M. and Rutten, F. (2007). Discounting in economic evaluations: Stepping forward towards optimal decision rules. Health Economics 16(3), 307–317.

- Krahn, M. and Gafni, A. (1993). Discounting in the evaluation of health care interventions. Medical Care 31, 403–418.

- Nord, E. (2011). Discounting future health benefits: The poverty of consistency arguments. Health Economics 20(1), 16–26.

- Paulden, M. and Claxton, K. (2012). Budget allocation and the revealed social rate of time preference for health. Health Economics 21(5), 612–618.

- Smith, D. and Gravelle, H. (2001). The practice of discounting in economic evaluations of healthcare interventions. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care 17(2), 236–243.

- Treasury, H. M. (2003). The Green Book: Appraisal and Evaluation in Central Government. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-green-book-appraisal-and-evaluation-in-central-governent

- Zhuang J., Liang, Z. and Lin, T. (2007). Theory and Practice in the Choice of Social Discount Rate for Cost–Benefit Analysis: A Survey. Asian Development Bank, Economics Working Papers Series. Available at: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/28360/wp094.pdf