Introduction: What Are Health Inequalities?

Health inequalities are observed in all societies. Although some inequalities may be considered unavoidable, resulting from sociodemographic characteristics such as age, gender, and genes, many of these health inequalities are associated with socioeconomic characteristics that are potentially amenable to policy interventions and could be considered as avoidable. In Europe, measuring and understanding these differences have been the major part of the literature on ‘health inequalities.’ In the US, these types of analyses are often referred to as ‘health disparities.’ For the purpose of this section the term ‘health inequalities’ will be used. It will also be assumed that it is clear what is meant by ‘health.’ Health, in this section could refer to a range of outcomes such as coronary heart disease, remaining expected quality adjusted life-years (QALYs), length of life lived, mortality, morbidity, etc.

Avoidable health inequalities are commonly defined as unfair systematic differences in health outcomes, although whether such inequalities are unfair may depend on the equity criterion applied. Inequalities are not generally considered unjust in cases where genes or the human body’s natural capacity are largely at play, for example, women tend to live longer than men, or 20-year olds in general have better health than 60-year olds. However, the marked differences evident in the populations of some countries in mortality rates (and other health measures) between occupational classes, between regions, between races, and between the rich and the poor are all considered to be examples of avoidable and unfair health inequalities. Researchers across the disciplines of economics, sociology, epidemiology, and psychology have suggested various theories that could explain health inequalities, and among these, theories regarding the influence of material factors – especially income – have been fundamental to the research into health inequalities.

The Link Between Income And Health

The association between levels of income and health is well documented, with research suggesting that income levels and health outcomes are positively correlated. At the individual level (and controlling for other factors such as age, gender, and socioeconomic characteristics), income is often found to be a significant predictor of health. However, the direction of causality is difficult to identify: Does higher (lower) income lead to better (worse) health, or does health affect income? Further, the causality may be direct, or indirect, with income and health affecting each other via mediating factors. It is also possible, although not likely, that there may be a third factor affecting both health and income, giving the impression of a relationship but without any causal link between them.

At the aggregate level, cross-country comparisons have shown that higher average income (gross domestic product (GDP) per capita) correlates with higher average health (in this case, measured as life expectancy). This is often known as the absolute income hypothesis (AIH). This evidence can be found for both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. The way average health has improved along with average income is clearly demonstrated here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v= jbkSRLYSojo

These data give a clear animated illustration of Preston curves that demonstrate a concave relationship between life expectancy and average income (measured as GDP per capita). This means that as average income increases, life expectancy increases at a decreasing rate, or still more simply, a proportionate increase in average income is associated with larger health gains at lower initial levels of average income than at higher initial levels of income.

However, this aggregate-level result does not seem to hold when GDP per capita reaches a certain level. In developed countries that have passed through the ‘epidemiological transition,’ where the main causes of death are chronic conditions rather than contagious diseases, there is little evidence of a relationship between income and health (countries are on the flatter part of the Preston curve). It is worth noting that the flatter part of the Preston curve only implies that there is no difference in average health by average income across societies, but there can still be variations in average health across income groups within societies. Based on this evidence, it has been proposed that absolute income is not the main determinant of health in developed countries.

Relative Income Hypothesis

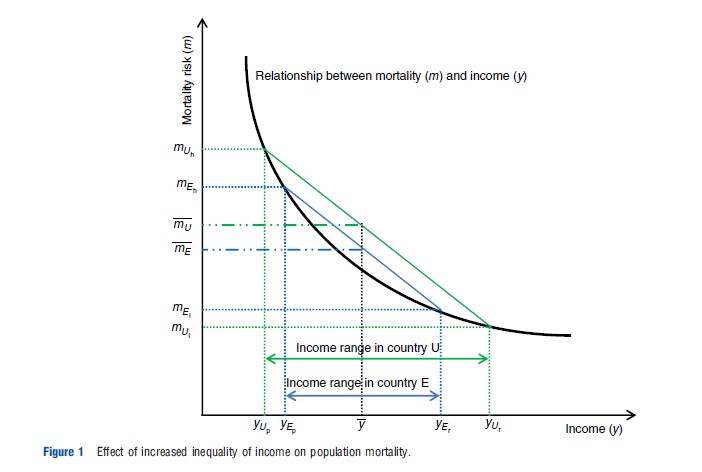

In developing countries, individual absolute income seems to be the main determinant of individual health. If income or material factors are important for health, then continuing growth in income should result in increasing health. Thus, for example, if mortality risk (or any other health outcome) at the individual level is convex (as shown in Figure 1) so that the risk of death decreases at a decreasing rate as income increases, then health inequalities should decrease as countries became richer – for example, ‘as they progress toward becoming developed countries. As income grows, those at the top end of the distribution see their health improve but at a slower rate than that of individuals at the lower end of the distribution (because of the steeper gradient for these individuals). So over time, health inequalities will disappear if all individuals see the benefits of income growth: if the relationship at the individual level becomes completely flat, then even if the income of the most wealthy grows at a faster rate than that of the least wealthy, health inequalities will diminish as long as the least wealthy experience some income growth.

However, this is not what is observed: health inequalities persist in developed countries and are even increasing in some instances. Although this may be explicable by the AIH due to those in the lower socioeconomic groups not benefiting from income growth, it may be that an alternative explanation is more likely. The most influential alternative theory to date is the relative income hypothesis (RIH), which has been developed most notably by Richard Wilkinson. In his groundbreaking work, Wilkinson (1996) identifies the possibility that it is the distribution of income within a country or region rather than the absolute level of income that causes inequalities in health. The essence of the theory is that income inequality negatively affects individual health. In its strongest form, this means that all individuals, even the richest, experience worse health when there is high income inequality. Weaker forms involve only those individuals who are at the lower end of the socioeconomic spectrum experiencing worse health.

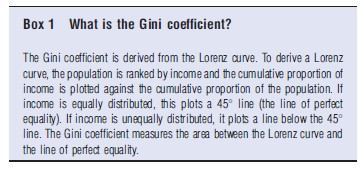

There is a large body of empirical evidence supporting the RIH using aggregate-level data. Measures of income inequality – the Gini coefficient is the most widely used – have been shown to have a significant negative association with health (measured either by life expectancy or by infant mortality): the larger a country’s Gini coefficient, the higher the income inequality and the worse its health outcomes (Box 1).

Studies investigating the relationship between average health and the share of income (by quintiles or percentiles of the study population) or the percentage of the population in relative poverty, all seem to confirm that the wider a country’s income distribution, the worse the average level of health in that country appears to be.

Theories Behind The Relative Income Hypothesis

The RIH has its theoretical basis in, and is supported by, evidence from sociology and epidemiology. From a sociological perspective, social cohesion and social capital (such as trust, participation, and social inclusion) are the bases for the RIH, with income inequality acting as a proxy for either a lack of social cohesion or a lack of social capital. Countries with a wide distribution of income are assumed to have fewer social support mechanisms, thereby leading to higher crime rates and a diminished quality of social environment. As a result, the health of every individual in these unequal societies will be affected directly via disease development or hindered recovery, and indirectly through health-damaging behaviors (such as smoking or substance abuse) when individuals at the lower end of the social scale react to their adverse circumstances. The psychosocial effects of living in an unequal society could also support the RIH, as inequality may cause stress or anger due to either a lack of social support networks or an inability to maintain a socially acceptable standard of living.

Epidemiology provides a large body of evidence of the impact of social status on health. Much of this work is summarized by Marmot in his book, Status Syndrome (2004). Studies suggest that health inequalities reach up the social scale because hierarchy and social regimentation are harmful to health: people at every level of the ‘pecking order’ suffer worse health than those above them. Income or income inequality acts as a proxy for the control in one’s life. In wider hierarchies, those at the bottom suffer more than those at the top. Such a premise is partly based on the flight or fight syndrome – where the body produces a reaction in times of stress of whether to fight or take flight. With the body under stress, there are detrimental impacts on individual health.

Neither of these approaches is without problems. The sociological psychosocial approach looks only at psychological effects and appears to disregard the material, behavioral, or biological factors that may cause ill health. The epidemiological evidence is criticized because it often does not control for income as being part of the study. Without controlling for individual income, it is always possible that this confounds the relationship between health and income inequality.

Aggregate-Level Data Problems

Much of the data used to investigate the relationship between income inequality and health are at the aggregate level, and although these ‘aggregate-level data studies have provided considerable evidence in favor of the RIH, it is important to recognize their limitations. The key limitation of aggregate-level studies is the aggregation problem, which occurs when the existence of a nonlinear relationship between health (e.g. mortality risk) and income at the individual level leads to spurious results at the aggregate level.

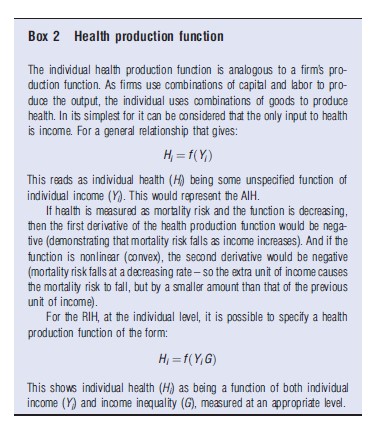

The aggregation problem is best explained by using an example: Assume that absolute income is the only factor affecting individual health (AIH) and the relationship is nonlinear, so the relationship between mortality risk and income is convex – as income increases the risk of death decreases at a decreasing rate. This situation was described earlier and it is illustrated in Figure 1. The framework can be considered as a health production function (see Box 2). In this situation, income inequality has no impact on individual health – it is absolute income and not relative income that matters.

Now imagine that there are two countries (these are illustrated in Figure 1 as Evenland (E) and Unevenland (U)). In each country, there are only two groups: the rich (yr) and the poor (yp). The average level of income is the same in both countries (y), but in Evenland, the difference between the incomes of the rich and the poor is smaller than in Unevenland.

The relationship between income and mortality risk (the graphical version of our convex health production function) is the same for both countries, which is the convex curve in Figure 1. Aggregating individuals and comparing average health in each country, shows that the average risk of mortality is lower in Evenland (mE ) than it is in Unevenland (mU ). From this aggregate-level evidence, it may be concluded that the distribution of income has a negative impact on health at the individual level; nevertheless, in fact, this would be a spurious conclusion because at the individual level, it has been assumed that there is no relationship between income distribution and health – it is only absolute income that matters.

In this example, the result mE <mU can be explained solely by the AIH with no reference to the RIH. This occurs simply because of the nonlinear relationship between health and income at the individual level: the poor individuals in Unevenland are on a steeper part of the production function than those in Evenland. Conversely, the rich individuals in Unevenland are on a flatter portion of the production function than those in Evenland. The aggregation problem is demonstrated in its mathematical form by Gravelle et al. (2002).

Despite the aggregation problem, this example does show that more even distributions of income have better health on average than more unequal distributions. Again consider Figure 1. This time instead of thinking of two countries being compared consider the same country at two different time points – time E and time U. There are still two groups, the poor (p) and the rich (r), and between times E and U, there is a redistribution of income from the poor to the rich that leaves average income unchanged (at y), but the income gap between the rich and the poor widens. Following the redistribution, the income of the poor falls from yEp to yUp , whereas the income of the rich increases from yEr to yUr . This leads to the mortality risk of the poor increasing from mEh to mUh , and the mortality risk of the rich decreasing from mEl to mUl . The increase in mortality risk for the poor outweighs the fall in risk for the rich, so mE <mU and overall mortality risk increases. This result stems purely from the impact of individual income on individual health (as predicted by the AIH) but clearly demonstrates why the distribution of income is important.

The aggregation problem highlights the need for individual-level studies to explore the RIH. Individual-level studies allow the exploration of the link between income inequality and health without having to deal with the aggregation problem. Lynch et al. (2004) have conducted a systematic review of the literature, investigating income inequality and health, and Jones and Wildman (2008) have considered the literature investigating relative deprivation and health. Although many of the results have been mixed – perhaps due to difficulties in a number of methodological and empirical issues, to be discussed in the next section – a recent meta-analysis does suggest a significant, if not causal, relationship between income inequality and health (Kondo et al., 2009). It is likely that income inequality and health are related at the individual level; however, there are many unresolved issues before reaching a more definitive conclusion.

Unresolved Issues

The RIH presents a number of unresolved issues. Firstly, studies often use cross-sectional data that assume a contemporaneous relationship between income, income inequality, and health. This assumption raises an identification problem, which has not been dealt with adequately. When considering the mechanisms by which income inequality may affect health, such as stress generated by being of low social status, lack of social cohesion, or an inability to purchase status goods to ‘keep up with the Joneses,’ then the contemporaneous specification may not be detecting the true nature of the influence of income inequality on health. The impact of all these mechanisms on health takes time to develop; for example, being of low status may have a cumulative detrimental impact over time, so ceteris paribus the impact on health will be greater for older individuals. Longitudinal data are needed to examine the impact of income inequality over an individual’s life course and whether the impact increases in severity over time.

Secondly, health can be measured across many different dimensions (e.g. expected lifetime QALYs, self-assessed health, long-standing limiting illness), but not all of these are sensitive to the effects of income inequality. If the psychosocial theory is correct, one would expect income inequality to have a greater effect on mental health measures than on measures of general health such as self-assessed health or physical health such as mortality or certain chronic illnesses. In addition, one may also expect a link between mental health and physical health, but the transitional effect from mental health to physical health may take time to develop. Furthermore, even though the observation of individuals over time provides the ability to control for unobservable heterogeneity, there are rarely data available that allow for the examination of the impact of inequality over the life course. So, if income inequality affects mental health, it may take even longer for the impacts to be revealed in more general health measures such as chronic illness or self-assessed health that are commonly collected in population surveys. To detect the psychosocial impact of income inequality on health, there is a need for longitudinal data with good measures of mental health.

Thirdly, investigating the RIH requires the construction of a relative income measure, namely, how an individual compares his or her income in society against a particular reference group; therefore, it is inevitable that investigations into the RIH are affected by the choice of a reference group against which individuals compare their income. There is no consensus in the literature on the reference group and there is no empirical solution to the problem – it is not possible to determine reference groups by observing behaviors because the choice of the reference group can itself be endogenous. Individuals may choose to compare their own income either with the average income of the country (region/town) they live in, or with the income of their peers, neighbors, people in the same age group, or any other plausible reference groups. Many of these reference group definitions have been used for research in this area.

A further issue for researchers is the measure of income inequality. The way in which this variable is constructed is yet another key element in understanding how income inequality affects health. The choice of measure can determine how income inequality appears to affect health. As noted above, the Gini coefficient is a commonly used measure of income inequality. Because this measure is an aggregate-level measure, there is only one Gini coefficient for any specific population wherein its use assumes that all individuals in that population are affected by income inequality in the same way. For example, in cross-national studies, each country has one Gini coefficient for any given year, and this means that there is no differential impact of income inequality for individuals within that country. Other methods have tried to create measures of income inequality that vary across individuals, and these measures are often considered to be measuring relative deprivation. Such measures compare an individual’s income to a reference point, which may be the median or the highest income in an area. Such an approach acknowledges that income inequality may affect some individuals more than others as the relative income deprivation measure of someone being further away from, for example, the median income, is larger than that of someone being closer to it. This does raise an issue about the asymmetry of the inequality effect – individuals are negatively affected by having people above them in the income distribution, but they are unaffected by having people below them. It may be possible that individuals gain satisfaction from looking down on people in the income distribution, but this position has not been widely considered in the literature, partly because it is difficult to disentangle the positive effects of being above people from the negative effects of being below them for any given individual in a distribution (except the one at the very bottom end and the one at the top end of the income distribution).

Finally, there are theoretical or modeling issues that may be fundamental to examining the RIH. The measures of income inequality are often functions of individual income, which may cause multicollinearity in a regression while controlling for the effect of income. The income inequality measures may directly enter into the health production function or utility function, or enter indirectly through third factors, or both, and this may require a whole new theoretical framework for constructing the relationship between income inequality and health. It could also be that as relative concerns allow such a broad range of behavior, their inclusion in choice models that theoretically consider individual behaviors may give them little or no predictive power. For these reasons, it is important to research and develop a proper theory underpinning the study of the RIH.

Conclusion

There is a substantial body of evidence linking inequalities in health with material factors, with income being considered as the most important factor. Recently, the RIH has been identified as an alternative explanation of health inequalities in developed nations. Initially, strong support for the RIH was provided by aggregate data studies, but these have been criticized because of the aggregation problem. Individual-level studies that overcome problems of aggregation have reported mixed results.

In recent years, research on income inequalities has widened its focus. Wilkinson and Pickett (2009) have considered the relationship between income inequality and a whole range of outcomes, including health and health behaviors (such as drug and alcohol addiction), social mobility, crime, well-being, and educational performances. This consideration of the relationship between income inequality and a wider range of outcomes suggests the importance of understanding the causal pathways at play.

Among both supporters and critics of the RIH, there appears to be a consensus calling for more research to model the effects of relative income on health from a broader perspective. Individuals live in societies and their behaviors need to be modeled and placed within a macro context in order to fully understand the relationship between income inequality and health; this would include individual-level characteristics and macro-level social factors such as social capital, social support mechanisms, and societal structures that cause inequalities. Developing a model to account for all these factors is the challenge for future research.

References:

- Gravelle, H., Wildman, J. and Sutton, M. (2002). Income, income inequality and health: What can we learn from aggregate data? Social Science and Medicine 54(4), 577–589.

- Jones, A. M. and Wildman, J. (2008). Health, income and relative deprivation: Evidence from the BHPS. Journal of Health Economics 27(304), 308–324.

- Kondo, N., Sembajwe, G., Kawachi, I., et al. (2009). Income inequality, mortality, and self-assessed health. British Medical Journal 339, b4471.

- Lynch, J., Davey Smith, G., Harper, S., et al. (2004). Is income inequality a determinant of population health? Part 1. A systematic review. Millbank Quarterly 82, 5–99.

- Marmot, M. (2004). Status syndrome. London: Bloomsbury.

- Wilkinson, R. (1996). Unhealthy societies: The afflictions of inequality. London: Routledge.

- Wilkinson, R. and Pickett, K. (2009). The spirit level: Why equality is better for everyone. London: Penguin.

- Deaton, A. (2003). Health, inequality, and economic development. Journal of Economic Literature 41(1), 113–158.

- Gravelle, H. (1998). How much of the relationship between population mortality and unequal distribution of income is a statistical artefact? British Medical Journal 314, 382–385.

- Wagstaff, A. and van Doorslaer, E. (2000). Income inequality and health: What does the literature tell us? Annual Review of Public Health 78, 19–29.