Introduction

This article provides an overview of public health policy, a basis for understanding what it is, and key definitions relevant to the subject; the various factors that can be used to explain policy making; how policy is or is not rationalized in practice; how health policy affects health systems, exemplified by analyzing how they are financed and governed; and the politics of health policy in the world today. A conclusion is then provided.

Clearly public health policy is – both in theory and in practice – an application of public policy more generally. It is therefore important to set it in the context of public policy and politics. It is equally important to appreciate that a global review of health policy with potential reference and relevance worldwide must concentrate on generic factors, yet with selective illustrations: principles of analysis, generic global trends, and illustrations of policy making and actual policy in different parts of the world.

Key Definitions

Health

It is crucial to define policy but also to give a brief account of how health is being defined and treated. Doing the latter first, health is defined in terms of its public aspect: The health of the public and therefore the responsibility and role of government and other agencies to meet public objectives for the public health. Public health is sometimes defined in a more specific way, that is, the particular set of programs and activities that seek to make an impact upon the promotion of better health, the prevention of ill health, and also environmental health.

Rather than the latter definition, this article refers to health policy in the broadest sense – affecting the health of the public – ranging, for example, from the effect of policy upon individuals’ access to care, on the one hand, to policy made overtly in pursuit of social goals for both the health-care system and health outcomes for the population, on the other hand. Its focus is upon policy, policy making, and the implementation of policy, but it is as well to be clear at the outset as to policy’s scope in terms of health. Policy can be negative as well as positive; for example, different health and health-care systems may affect health care for – and the health of – individuals, groups, and the whole population by what it omits as well as what it provides. With this in mind, let us turn to policy as the basis for understanding health policy.

Policy

A pragmatic definition of public policy would be what the government does (just as the British Cabinet Minister in the post-war government, Herbert Morrison, defined socialism as what Labour governments do!). This puts the emphasis as much upon public as upon policy: On its own, policy can be used in relation to any organization, public or private (e.g., it is the policy of the firm to specialize in luxury goods). But we need to go beyond such a pragmatic definition in order to unpack and examine the concept.

Politics, Policy, and Administration

Our concern here is indeed with public policy (as the means to understanding health policy). Policy comes from the Greek polis, which meant a city or more relevantly city-state and also gave rise to the term polity, i.e., political unit of self-government or the political part of a society, i.e., (in classical terms) the state. Policy came to mean the statecraft of the (modern) state. Etymologically it is bound up intricately with politics. But this is not just of historical curiosity. For public policy is embedded in politics – the politics embodied by the government, the politics of those who advise the government, the political ideologies that shape one’s political ideas, the political structures required to pass legislation, and the administrative, managerial, and social structures and personnel required to implement policy (that is, to produce social outcomes from policy outputs).

In the French language, for example, la politique can mean either politics or policy; the two are not distinguished (Hill, 1997). In traditional British language referring to the traditional British approach to statecraft, on the other hand, the word was often missing: There was politics, on the one hand, and administration, on the other hand. Hence the salience of the academic subdiscipline, public administration, which persists to this day, even in an age when the real world rather disparages administration, turning first to management and then to leadership. It persists no doubt in part because of convention (see for example the spread from the United States to the rest of the world of MPAs – Masters Degrees in Public Administration – even when the subject matter is modern business, management, and leadership). But it may also persist because there is a healthy skepticism in certain parts of academe about whether or not we should merge (private sector-derived) concepts of management and leadership with the overall terrain of government and its output – which may well be called public administration with some degree of accuracy (Hood and Scott, 2000).

Between these two extremes (French and British) above, there is the domain of public policy, which is different from politics (although intertwined with it) and also different from administration with the connotation of the civil service that takes politics/policy, codifies it, and translates it into systems capable of being implemented in the field. This domain recognizes policy’s intimate relations to other domains but still thinks it worthwhile to give it a domain of its own. That is my perspective, broadly, in this article.

Public Policy

Going beyond the pragmatic definition of public policy as what the government does, it can be defined as the outputs from a process geared to making laws, enactments, and even regulations that are intended to affect society, i.e., produce social outputs and outcomes as a result of the outputs from the political system that we may call policy. Note that, in some countries, systems, and cultures, policy even by this definition may not be handled primarily by the politicians, but this is in itself a (political) characteristic of the political system.

On this approach to the process, the inputs are various (Paton, 2006a). They range from ideas and ideologies, through the political culture, through political movements or parties, through the effect of political institutions and structures generally, through social movements, interests, and pressure groups, through dominant modes of behavior (whether rational or otherwise), to the administrative or bureaucratic culture. Below, I examine the key factors involved.

Meanwhile, selectively, the following section defines some more terms.

General Terms

- Environment/context: The external climate and actual constraints, or pressures, which influence policy. For example: In the economic environment of global capitalism, it is difficult for individual countries to create or maintain progressive taxation systems with high tax rates, and the prospects for expanding public health-care systems are therefore diminished.

- Actors/agents/stakeholders: All those individuals, groups, interests, agencies, and organizations that are involved with, concerned with, or affected by, a specific policy (see Kingdon, 1984; Buse et al., 2005).

- Agenda: The terms of debate on which an issue is developed in the policy process, or the prioritizing of one issue rather than another – or none – in the political process, or in an agent’s schedule (see Kingdon, 1984).

- Problem: Seemingly straightforward (for example, ‘‘the primary problem with the British NHS in the 1990s was long waiting times’’) but useful when considering how agendas are formed (e.g., is there agreement as to what the problem(s) is/are), and how politics, problems, and policies interact (John, 1999; Paton, 2006a).

- Power: The ability of Actor A to win in an overt political battle (Dahl, 1980) (in our case, in the health policy arena) with B; or the ability of A to prevent B from raising an issue (effectively) within the political process (Bachrach and Baratz, 1970); or the ability of A to prevent B from even being aware he has a grievance or should have a grievance (see Crenson, 1971; Lukes, 1974); or the effect of the dominant (or prevailing, or pervasive) discourse upon the perception of issues (in the poststructuralist sense, in terms of the effects of language upon concepts and thought) (Peck and Coyle, 2002: 214–219). Note that the last definition de-centers the actor – power is less a conscious attempt to win, by an agent, than an effect.

Practical Terms for the (Health) Policy World

- Regulation: A framework of rules (e.g., a legally backed code) or practices (e.g., by an inspecting agency) that define permitted activity, or type and mode of activity, in a field, as opposed to planning or management, which intervene directly rather than set a framework for self-action. For example, the new regulation in health care sets out the rules for markets or quasimarkets, in formerly directly managed health-care systems. Day and Klein (1987) argued that a regulator is external (so that, for example, a higher tier within a public health-care system does not regulate but instructs or manages).

- Strategy: Often contrasted with (on the one hand) tactics, it refers to the means of achieving a direction of travel or goal (as in military strategy), e.g., ‘‘the strategy for involving the public more in decision-making is to set up local self-governing units in the healthcare system’’; contrasted (on the other hand) with an operational focus on keeping things running, as in ‘‘the Health Authority’s Director of Strategy will ensure that our plans are consistent with our goal of improving access to the under-served; whereas the Director of Operations will seek to increase throughput in the wards to meet government targets.’’

- Governance: Within public services such as health care, the adoption of an appropriate structure and culture of oversight of the organization (as in corporate governance, which seeks to assure that the organization is run and controlled ethically, soundly, sustainably and appropriately; or clinical governance, which is the corporate governance of the clinical process in particular).

Explaining Public Policy

Through one interpretation, actors (e.g., policy makers) are rational. This might be in the sense of either maximizing their utility (the neoclassical microeconomic viewpoint) or planning a coherent – perhaps evidence-based – route to achievement of objectives, i.e., the tailoring of means to ends.

This latter view is found in political and administrative science, e.g., in Allison (1971). The question is begged as to whether such rationality commands consensus (the unitarist view, or Allison’s Model 1 when applied to policy making within the portals of central government) or whether different interests, elites, structural interests, or economic classes – either in government or across the wider polity and society – have different objectives (respectively, the pluralist, elitist, corporatist, or Marxist views) (Paton, 2006a). These different objectives might be rational on the terms of the individuals and groups who have them, and they may be pursued rationally in terms of the instrumental tailoring of means to needs. Yet the overall effect is not consensual pursuit of universally acknowledged rational outcomes. Instead there may be pluralism, with compromise as the basis for outcome – leading, perhaps, to incremental, small-scale policy changes overall even when each group or interest seeks radical, large-scale change. (Compromise is a very different thing from consensus, although there may be eventual consensus upon the need for, and nature of, compromise.) Or indeed there may be domination by an elite or ruling class, which creates a dominant agenda. This may look like rationalism, not least in terms of the passage of comprehensive policy rather than cautious adjustment, but is a very different thing, once again.

One may also consider actors seeking to achieve their chosen outputs and outcomes (as defined above), but tailoring their behavior in line with the incentives created or enhanced by the institutions’ way of working. This is institutional rational choice (Dunleavy, 1989).

But perhaps the culture created or encouraged by structures, and the behavior they encourage, takes on a life of its own: There is a mobilization of bias (Schattschneider, 1960; Paton, 1990) in policy. This may be due to the effect of external structures upon people’s expectations and ways of thinking (i.e., cognitive structures) rather than (just) upon the calculations of autonomous rational actors whose thought processes and agency are unaffected by structures.

Indeed there is a difficulty with assuming that humans have an unchanging, rational, or maximizing nature – what Archer calls Modernist Man (Archer, 2000).While it has the merit of preventing the agent from being (implausibly) completely subsumed by society, it begs the question as to where this intrinsic nature comes from. Not only are the assumptions behind rational man questionable (an ontological matter), but their origin is too (an epistemological matter).

Structuralism (Peck and Coyle, 2002: 211–214) arguably solves the dualism by going too far in the other direction. It either removes man’s autonomy, positing that deep cognitive or real (natural or social) structures dominate agency. Poststructuralism posits that structures are linguistically determined but variable, indeed arbitrary (Peck and Coyle, 2002: 214–219). On this approach, varying discourses and perspectives that are thus based are constitutive of the individual. The paradox is that the agent is no longer determined by deep or unchanging structures but that there seems no basis for agency other than by changing language. On this basis, agents qua policy makers are neither rational nor irrational: There is no objective basis for evaluating their actions.

Other approaches point to the actor’s autonomy being limited but not eradicated. In public administration, this might provide a useful reminder of the role of cultures, ideologies, and ideas in policy studies.

Particular structures of relevance to health policy are political institutions, governmental and administrative structures, and specific health agencies. We may wish to define culture separately from structure, or to interpret cultures, habits, and beliefs (including ideologies and ideas) as structures for the present purpose – identifying external factors when seeking to explain or influence policy.

The literature concerning the factors that influence, shape, and even cause public policy is now immense. It is necessary to walk the tightrope between theory, on the one hand, and plausible explanation of what is actually happening in the real world, on the other hand. Rhodes (in Stoker, 2000) stated memorably that social science can cope with a lot of hindsight, a little insight, and almost no foresight! Thus it is with explanations of public policy.

The policy process (Hill, 1997) is a phrase that characterizes the story of how policies develop, are implemented, in often unpredictable or even perverse ways, and are amended, in a process that is less linear than (variously) wave-like, stew-like, cyclical, and even circular. It should also be understood to encapsulate how politics both shapes and is shaped by policy and the social outcomes that result from policy outputs.

Explanatory Factors (Illustrated for Health)

The key factors used in political science and public administration to explain outputs and outcomes in public policy are:

- Political economy (generally, and also embracing regime or regulation theory) (Aglietta, 1979; Jessop, 2002): Political economy can be defined as the way in which wealth is produced and distributed. It is a crucial backdrop to understanding the underlying pressures and constraints upon health policy. The global capitalist economy puts significant pressures upon public health systems, as well as (for some countries) generating wealth and income that can be used for both private and public purchasing of health care. Additionally, effects upon health outside the health-care system altogether can affect health both positively and negatively. How public policy generally and health policy in particular interact in this environment is crucial.

For most but not all countries of the world, current international political economy as opposed to purely national political economy is more important than during the period from 1945 to 1975, which was an era of expansion of economies and of the welfare state in what was then called the industrialized West; expansion which had knock-on effects elsewhere around the globe. Subsequent retrenchment, plus a (related) change in dominant type of political economy (or regime), has had significant effects on health-care systems.

The first wave of global health sector reform in the 1940s and 1950s (WHO, 2000a) consisted in the establishment of national health-care systems in many countries. The second wave (1960s and 1970s) consisted in primary health care as a strategy for affordable universal coverage (given already experienced cost pressures) in developing countries. The third wave – moving into the 1980s and beyond – consisted in a move away from statist public systems to either public or mixed systems relying more on market, quasi-market, or new public management mechanisms (WHO, 2000a).

- Socioeconomic factors. These are distinguished from (1), although they are related in that they refer to data and demographics, such as the level of wealth of a country and the distribution of wealth and income. Health and welfare expenditure, for example, has been correlated to the former (see Wilensky, 1974; Maxwell, 1982).

- Institutionalist, new institutionalist, and structural explanations, which give primacy to the effect of political institutions (and the behavior and incentives that they create) in explaining policy outputs (Dowding, 1990; Paton 1990). In health policy, policy may result both from the way institutions operate and also how they create a dependency that constrains future policy or directs it in a particular way.

- Institution-based rational choice. Individuals may act in groups or share interests which influence their behavior, yet have goals and objectives that are determined independently of political structures (institutions) and of cultural factors (for example, a putative dominant ideology). Nevertheless, their behavior is influenced by institutions and the incentives to which the latter give rise, as they seek to achieve their objectives in the most rational manner. This is a version of institutional rational choice (which, as Dowding (1990) points out, need not be methodologically individualist).

Original or pure rational choice theory as applied to politics was individualist. Public choice theory was based on the view that both individuals and agencies (collectivities of individuals) are selfish maximizers. The implications were that bureaux and bureaucracies would seek to maximize their budget beyond the point of efficiency or effectiveness. For example, the chiefs of a health department – or publicly funded hospital system – would use the political process (perhaps in coalition with politicians, civil servants, and doctors, all building their empires) to expand.

This was one of the rationales for the purchaser/ provider split (Osborne and Gaebler, 1993), which has featured significantly in both the theory and practice of health sector reform since the late 1980s and 1990s. The trend started in developed countries, particularly the UK and New Zealand (Paton et al., 2000). Countries with public or publicly regulated insurance in central Europe systems, such as the Bismarckian systems of social insurance (Paton et al., 2000), always had financier/ provider splits in the tautologous sense that payers and insurers were separate entities from providers. But this is merely the traditional system that operated through guilds (self-governing providers, professions, and payers regulated by the state) relating to each other without much competition. It is not the same thing as a deliberately created quasi-market or new public management reform.

The latter has also been used to reform Bismarckian systems by instigating competition between payers and insurers (whether public or private) for subscribers. Providers of services would have to justify their product (effectiveness) and their costs (efficiency) through tendering competitively in order to win a contract, or at least, if competition was not possible, through setting out clearly their services in response to a specification that might be contestable in the longer run if it was unacceptable in cost or quality.

The trouble with this was that purchasing authorities and agencies would also be selfish maximizers if the theory were right. Who would control them? The answer – especially in health care – has often been a system regulator (Saltman et al., 2002). But the same applies to the regulator! So we are driven back to government, as the regulator of regulators. And who controls government? The answer is (idealistically) the people or (realistically) special interests or the ruling class. There is no technical solution – such as purchaser/provider splits – to what is in essence a political problem.

- Issues of power, of how power is distributed in society and within the political system, and how it influences public policy. For example, is power distributed pluralistically, or are decisions taken by – or in the interests of – the ruling elite or a ruling class? Here, it is important to distinguish instrumentalism (arguing that, if politics and policy benefit a group, elite, or class, how this occurs must be actually demonstrated) and functionalism (which implies that means that are functional for ends somehow are realized).

An example of using functionalism to defend Marxism, for example, was found in Cohen (1978) A strong variant of functionalism is evolutionism, which draws an analogy with Darwinism in natural science to imply that the policies that come to dominate are those best suited to surviving in their (political) environment (John, 1999).

Functionalism implies that policies develop because they are functional for the external environment, whereas evolutionism implies that policies develop if the external environment is functional for them. Neither stance is satisfactory, as the how is missing. And evolutionism in particular – in social science and policy studies – is either tautologous or vacuous. This is because, unlike in the natural world, the environment is human-made and mutable and can be made functional for policies. Anything can therefore be explained in this manner.

The classic example of power in health policy has concerned the medical profession and its relationship both with other actors in health-care systems (especially managers) and with the state.

Network theory, whether sociological, political, or managerial, has had prominence recently. To some it is descriptive rather than analytical (Dowding, 1995), although if integrated with power studies (i.e., networks explained in terms of power and influence) it can be useful (Marsh, 1998). At its best, it has the potential to explore how regimes at various levels of government (international, national, and local) are responsible for investment and consumption, and therefore to link political economy with institutional and behavioral analysis.

For example, the corporatist approach – which depicts iron triangles of business, government, and labor in policy decision making (see for example Cawson, 1986) – was extended to depict how national government organizes investment and local government organizes consumption. More recently, in the global and European era, local and regional government and governance are responsible for investment to a greater extent, with national government ironically increasingly controlling or circumscribing consumption. This is related to a (concealed) change in power relations in the economy, with corporatist trilateralism replaced with the bilateralism of business and the state.

- Ideas and ideologies, which are important, but often linked to wider social factors (and political economy), and in complicated ways. An approach emphasizing the primacy of ideas may sound rational. On the other hand, an approach emphasizing ideology may be ambiguous. Ideology can suggest moral goals and a program to achieve them, or it can suggest false consciousness of agents who are cultural dupes. In health, the primary care movement is sometimes seen as ideologically motivated. Equally Navarro (1978) has argued that high-technology medicine is a means of buying off workers given the disadvantages of (and lack of effective public health in) capitalist society.

A Synthesis

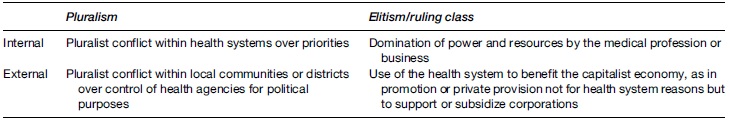

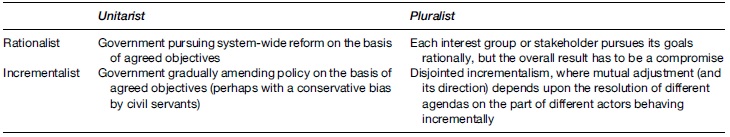

Clearly, different factors can be combined in explaining public (and health) policy. Different typologies are available to aid with this task (see Tables 1 and 2)

Table 1 Power

Table 2 Type and degree of rationality

Two examples are provided:

- Policy may be made for health, or it may be made with other factors in mind (e.g., trade, the economy).We can call these, respectively, internal and external policy. Additionally, power may be distributed widely in making – or implementing – policy, or it may be concentrated. We can call these, respectively, pluralism and elitism (or ruling class theory). Table 1 shows four possibilities, with four health examples. The aim is not to develop grand theory but to provide a checklist or an aide me?moire when examining empirical possibilities.

- Policy may be made from a zero base on the basis of seeking means to achieve ends on which there is agreement (either within government or in wider society). This can be called rationalism. Alternatively, it might be made incrementally, on the basis of minor adjustments to previous policy (see the second paragraph in ‘Explaining public policy’ above).

Additionally, policy may be made consensually (or with only one viewpoint featuring, not the same thing), which variants can all be termed unitarism. This in turn can be contrasted with pluralism (defined as in Example 1). This time, the latter refers more to the breadth of influence upon central government than to the nature of social power more generally.

Table 2 shows four possibilities. As with Table 1, it illustrates and clarifies rather than helps decide, which must be done on a context-specific basis, i.e., empirically rather than a priori.

Explaining Implementation

A framework for explaining implementation can begin simply, analyzing inputs, outputs, and outcomes. Inputs draw on aspects of the explanatory factors described above, translated into concrete terms. It is helpful to categorize these as ideas, institutions, and political behavior (e.g., by political parties). At root the structure versus agency debate in social science (Archer, 2000) is at the heart of the issue: Individuals operating in (structural) contexts, individually or collectively, help to determine outputs and outcomes.

While ideas versus institutions has long been a talking point in policy analysis (King, 1973; Heidenheimer et al., 1975), these inputs produce outputs in the form of public policy. Implementation concerns the process by which such outputs (e.g., laws; an organization’s objectives) are translated into social outcomes. For example, health policy may concern the creation of a publicly funded national health service (NHS). The effect of the NHS upon access to services and health inequalities (for example) occurs as a result of how, where, and when the policy is implemented.

It is possible to have good policy but bad implementation and vice versa (Paton, 2007: Chapter 5). The former may occur when policy is designed (and enacted) rationally, but without taking into account opposition that later is mobilized effectively during the implementation phase. The latter may occur when policy is enacted after significant, possibly debilitating, compromise, but then implemented in a straightforward manner, as all opposition has already been taken into account.

Regulation is a means of seeking to achieve goals and objectives though a process of implementation, which occurs through self-modification of behavior in response to external rules rather than by direct command and control. Clearly, this is a pertinent issue in health policy, where international trends overtly embrace the new governance through regulation rather than direct control. The recent reorganization of the UK Department of Health (Greer, 2007) (which administers the English NHS but not those of Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland) reflects the creation of many quangos (external public agencies) allegedly to replace direct control by government.

There are, broadly, three systems of governance for implementing health policy. Firstly, there is what economists call by the catch- all term of hierarchy (i.e. one word as an alternative to markets) but which may be better described, on examination, as classical bureaucracy or – not the same thing – planning. This is sometimes described as command and control. Often this has pejorative overtones, but it need not: Bureaucracy has advantages in both normative and practical terms. These may include equity, consistency, and transparency (normative) as well as an ability to rationalize systems, reduce inappropriate discretion, and minimize unintended outcomes from local action (practical). Furthermore, the term hierarchy may be inappropriate to describe planning, in health care at least: The latter may eschew the market (see below), but allow considerable devolution of responsibility in meeting goals (Paton, et al., 1998; Paton, 2007).

Secondly, there is the market. Many countries have recently sought to use both market incentives within the public sector (Paton et al., 2000) and private provision to reshape their health-care systems.

Thirdly, there is guild self-regulation. This approach has historically existed in central Europe and also some countries in Latin America as the basis by which the government guarantees access (national health insurance) but providers, payers, and professionals self-regulate to a large extent, often in the context of a corporatism in which quasi-official, nongovernment agencies manage agreement about pay, the prices of services, and market entry.

It has been argued that providers (especially professionals) have knavish as well as knightly tendencies and that guild self-regulation requires both an assumption of altruism (Le Grand, 2003) and the assumption that providers respond to the correct signals in supplying services. Generally policy advocates such as Le Grand (2003) suggest the market as the answer. Yet it is vital to examine what happens when politics meets economics in market-driven health systems, which notoriously produce perverse results (Paton, 2007).

Furthermore, hierarchy, or command, need not be based on the assumption that providers (and managers in health care) only behave in a self-interested (knavish) manner. Planning approaches in health care, with official targets, may be a means of coordinating altruistic public service as well as providing material incentives for compliance.

Clinical networks, bringing together professionals from different institutions, may (for example) require both (internal) coordination and (external) compatibility with wider policy and managerial objectives. To replace these with atomized market incentives may encourage knavish behavior rather than channel it.

In terms of global health policy, we have the paradox that the ideology of the market sometimes continues to be on the ascendant but that its effects upon implementation are complex and often perverse (Segall, 2000; Blas, 2005).

Policy in Practice

The seemingly random interplay of ideas, groups organized around ideas, interests or advocacy (combining both values and interests; Hann, 1995), and opportunities for policy decisions leads us to the garbage can approach (Cohen et al., 1972). Policy now seems an arbitrary mess. And it may be, at one level or for some of the time. Agendas are successful, in this approach, not because of rationality but because of time or timing and chance (Kingdon, 1984). Policy, politics, and problems are separate streams rather than components of a rational process, and only when they flow together is policy created. This might, for example, be when politicians seize an answer (i.e., a policy) because it is available, trendy, and (coincidentally rather than logically) seemingly an answer to a problem that is perceived to be pressing.

The question then arises: If policies emerge haphazardly, one after another, how is policy rationalized, if indeed it is, to ensure that the aims of the state are realized or that policy outputs, at least to a minimal extent, achieve the social outcomes required for both the legitimacy of the state and the requisite stability of institutions? This is a more fundamental question than one about the aims of government. Clearly individual governments’ aims simply may not be realized. Nor should one assume that there is some teleology or functionalism favoring the aims of the state.

My argument is a different one, which can be illustrated from health policy. An institution such as the British NHS is only politically legitimate and economically viable if it satisfies several conditions: Investment in cadres of domestic workers occupying salient niches in the international economy; acceptability to the demanding middle classes, in terms of both quality and financial outlay (i.e., comparable to what they would pay if only insuring themselves); and fulfillment of its egalitarian founding mission at least to the extent that it seems worth the moral bother of protecting in the first place.

How can action by the state or its agents seek to fulfill these conditions? How in other words does the political realm ensure the compatibility of social institutions (such as the NHS) with economic reproduction? This is the crucial question for the sustainability of public health systems in the era of global capitalism.

There is no inevitability here. The state may act effectively to square the circle – not just of competing social demands in the conventional sense, but of the competing agendas listed two paragraphs above. If it does not or cannot – for example, if a country’s public health service does not satisfy employers’ needs and demands for healthy employees – employers will seek to finance their own occupational health. If doctors fail to cooperate at least adequately to prioritize the outputs and outcomes that the state requires, then either they will be coerced into doing so within the NHS or they will be disciplined by market forces outside the NHS, as corporations take responsibility for health care on a sectional basis (perhaps taking advantage of European Union law).

What this does, then, is give governments that are sympathetic to preserving at least publicly financed health care an interest in ensuring that the state coordinates policy at the end of the day, so that a complex amalgam of aims can be furthered. There is in practice a major conflict between the garbage can that produces continual waves of incompatible, media-driven policy, mostly in the developed world (Paton, 2006) or policy distorted by the predatory state (Martinussen, 1994), mostly in the developing world, on the one hand; and the need for effective coordination, on the other hand.

The latter means tight control of resources given the ambitiousness and complexity of aims, which means political centralism against all prevailing rhetoric. Most devolution and decentralization in state-dominated health systems is devolution of responsibility for functions, not devolution of power. Again, we can see that, in order to explain public policy outputs, we have to consider, respectively, the backdrop of political economy; social power; the structure of the state and political institutions; and how individuals, groups, interests, and classes behave in the context of the structures they must use.

For example, Allison’s (1971) Model 1 posits a unified executive pursuing the national good, having been developed empirically to explain the U.S. government’s behavior during the Cuban missile crisis. It is therefore a kind of grounded theory that is context-specific, and therefore the model may be less suitable for wider explanation of social decision making, interest-group politics, and power.

The challenge is to incorporate different explanatory factors at different levels of analysis. These levels can be considered to be a hierarchy in that there is a move from the underlying to the immediate in terms of their causal nature as regards policy outputs, but this is heuristic rather than wholly empirical. It is important not to be too rigid about (for example) what is undoubtedly a two way relationship between political structure and social power: The latter will exert itself, except in exceptional circumstances, through different forms of structure, it is true; but the former’s mode of channeling power may alter the nature of that power in so doing.

For example, the medical profession was powerful, as a stratum within a social and economic elite in the 30 postwar years of the last century, in both the United Kingdom and the United States. It was capable of exerting its power through the then very different political institutions of the United Kingdom and the United States. In the centralized, executive-heavy UK with (then) a political culture of insider networks that were relatively invisible (like all effective power!), an implicit bargain was made through informal channels between the state and the profession (Klein, 1990), which meant a symbiotic relationship in governing the NHS. In the United States, with its decentralized interest-group politics as the stuff of the system, the profession preserved its power using different institutions in different ways, primarily by blocking reform (in the way that the insurance industry did with the Clinton Plan in the 1990s (Mann and Ornstein, 1995; Paton, 1996), by which time it had replaced the now toothless tiger of the American Medical Association (AMA) as the lobby feared by reforming legislators).

The question that arises is: Is power economically rooted at base, with the decline in the AMA’s – and the wider medical profession’s – power caused by a surplus of doctors, on the one hand, by comparison with the 1950s and 1960s (when access to health care was extended by government, and the medical profession’s fears of socialization were shown to be ideological rather than economic), and by new corporate approaches to purchasing and organizing health care for their workers, on the other hand?

There is clearly truth in this. Yet it is not the whole story. The centralist UK political system was capable of more systematic reform – including the creation of the NHS itself – than in the United States, when the UK state was governed by a strong political party with clear and comprehensive aims, in other words, majority rule rather than the passage of policy by the painstaking assemblage of winning coalitions in the legislature. The latter creates a mobilization of bias (Schattschneider, 1960) away from comprehensive or rationalist reform as opposed to incremental reform, which in turn alters mindsets and limit ambitions. That is, structures can have cultural and ideological effects.

It is important to study an issue such as health policy over a long enough period (subjectively, about 20–30 years, in today’s world) to allow different eras to register and therefore the changing salience of different explanatory factors in public policy. In a nutshell, the 1970s was the era of political structures, as the prevailing political economy was nationally based; the 2000s are the era of political economy, as capitalist globalism reduces the salience of nations and their institutions.

In other words, political economy is at the top of the hierarchy of salient factors in delimiting and explaining public policy. It sets the background, environment, and constraints. Depicting a regime in political economy shows how the state and other elements of the polity come together to steer the economy in a particular way. It is Marxist, in that it prioritizes economic production, situates political viability and legitimacy in terms of the political economy and has crisis as the motivation to move from one type of regime to another (for example, from the Keynesian national welfare state to the Schumpeterian workfare state, in the language of Jessop (2002)). It is, however, post-Marxist or non-Marxist in that regimes vary within capitalism, that is, a regime is less than a mode of production in the Marxist sense.

Institutions and political structures shape behavior, partly by channeling rational behavior (i.e., institutional rational choice) but also by changing cultures and expectations, which feed into future ideas for policy, reform, or whatever, as outlined above. For example, in the United States, the failure of successive attempts at federal health reform, foundering on the rocks of established structures and interests inhabiting them, has lowered expectations for future action on the part of many reformers even without them realizing.

Power is exerted, that is, through institutions overtly and covertly, but the latter equates neither to Lukes’ (1974) nor to the poststructuralist vision of dialogues that are enclosed and arbitrary. Loss of ambition in reform ideas is a fatalism, in this sense, rather than a false consciousness, perhaps because elites are systematically lucky (in Dowding’s (1990) arresting oxymoron). In the end, it is just that, an oxymoron, because – with reflexivity of actors and even of passive public(s) – those who are systematically lucky are likely to go beyond luck, i.e., to build on it in a deliberate strategy to maximize their instrumental power.

Political structures and institutions vary between countries (as well as sub- and supranational levels). Thus executives vary in structure, scope, salience, and power, within the political system in general and state in particular. Regimes are more than governments and less than state systems. In health policy, regimes embody the prevailing orthodoxy in ideas (or ideology) as adapted to, and amended by, political institutions and social structures.

Policy for Financing Health Care and Structuring Health Systems

We can illustrate how health policy reflects a variety of different influences by examining how health systems may be financed and governed.

Financing Options

The main options for financing health care (ranged along a continuum from private to public) are as follows:

- private payment (out of pocket), including partial private payment, i.e., co-payments (coinsurance or deductibles) (coinsurance means the consumer paying a proportion of the cost, e.g., 20%; a deductible means the consumer paying a fixed amount on each claim, e.g., $50);

- voluntary private insurance, including partial versions (e.g., supplementary and complementary insurance, to be discussed below);

- statutory private insurance regulated by the state (including partial versions such as substitutive insurance, meaning – in this option – mandatory private contributions by certain categories of citizen (generally the better-off) toward core rather than supplementary or optional health services. That is, everyone is covered, but the better-off pay a form of insurance that is obligatory;

- community pooling;

- public/social insurance;

- hypothecated (earmarked) health taxation;

- general taxation.

Assessment of Options Against Criteria

A specific policy analysis would assess options, one by one, against identified criteria and (perhaps) incorporate a weighting procedure to rank the options. From the viewpoint of understanding how policy is actually made, however, this would only be part of the picture.

It might constitute an attempt at rational policy making, that is, an attempt to provide a basis for scientific consensus among the key actors holding power in either the policy process generally or government in particular. Alternatively, it might seek to build in to the criteria for judging options (or even, to the options themselves) pragmatic or political factors (such as the political feasibility of an option in a particular political context).

Either way, it is important to be explicit about the range of factors likely to affect a policy’s success as regards both enactment and implementation (i.e., outputs and outcome, respectively), as explored in the sections titled ‘Explaining public policy’ and ‘Policy in practice’. Otherwise, there is a divorce in the policy dialogue between what might be termed technocrats (such as economists), on the one hand, and political scientists on the other. The divorce between such worlds is often responsible for extremes of optimism and disillusionment, respectively, in assessing policy ex ante and ex post, as with recent health reform programs in England, for example.

Governance

There are fundamentally three categories of system:

- statist systems;

- market systems (whether private, public, or mixed);

- self-governing systems (with varying degrees of state regulation) (Arts and Gelissen, 2002), in which either guilds or organized functional interests or networks (of providers, financiers, and employees) organize the delivery of care.

Statist systems have replaced the market with public planning, whether it is dominated by politics, the public, or experts. Market systems rely on either private markets that have evolved historically or on the creation of market structures and incentives within (formerly) publicly planned systems. Self-governing systems are systems where central state control is limited or weak or both, but where guild-like relationships rather than market relationships between key actors predominate. For example, physicians’ associations, insurers’ associations, and the state will thrash out deals in a corporatist manner, with corporatism meaning (in this context) the institutionalization of major social interests into a reasonably stable decision-making machinery overseen by – but not dominated by – the state.

Clearly most advanced health-care systems are hybrids in varying degrees. The question is whether the degree of hybridity is dysfunctional or not, i.e., whether cultures and incentives are adequately aligned throughout the system.

Using the language of incentives, it is important to distinguish between macro and micro incentives. Statist systems, for example, are generally good (often too good!) at macro cost control; their record in terms of micro-level allocations (e.g., to providers or clinical teams) to achieve objectives is variable (a statement that should be taken at face-value; some are good at it; others are not). Those systems that allow meso-level planning authorities, such as regions, to avoid the excesses of both central control and local capture by unrepresentative interests, often have the capacity to square the circle in terms of incentives, as long as attention is paid to steering the system to achieve desired outcomes.

While all systems are likely to be hybrids, it is important to ensure that the dominant incentives, geared to achieving the most important objectives agreed by government on behalf of society, are not stymied by crosscutting policies with separate incentives. This has been an occupational hazard of (for example) England in recent years, arguably, with four different policy streams vying for dominance: The purchaser/provider split inherited from the 1990s’ old market and deepened by the creation of Primary Care Trusts; local collaboration as an alleged third-way alternative to state control and markets; central control through myriads of targets; and the new market of patient choice implemented alongside payment by results (Paton, 2005a, 2005b).

In consequence, in considering structures, attention ought to be paid to the central structure, i.e., how the political level is and is not distinguished in terms of governance from the top management, i.e., health executive level. There is no one answer (again, as the United Kingdom and especially England’s volte faces on whether or not health ought to be managed strategically at arm’s length from government or not probably show). Nevertheless, the question ought to be considered in terms of roles and functions of the different levels within a coherent governance structure: Is the system capable of articulating consistent policy?

The Politics of Policy Analysis and Policy Outcomes

Policy studies have evolved the term path dependency to illustrate how historical choices create paths that constrain (although do not necessarily determine) future options. This is sometimes allied with the concept of the new institutionalism, which is actually just a way of emphasizing that agency, ideas, and ideologies are only part of the picture.

For example, policy debates vary from country to country – say, in terms of how to reform health services or with regard to the best type of health-care systems – for reasons that do not involve only the cultural relativism of ideas. There are relatively universal typologies of health-care systems, analyzed along dimensions such as how universal coverage is, how comprehensive services are, and how payment is made. Yet these debates are handled very differently, with different results, in domestic policy communities in different countries, even when these countries might seem fairly similar in global terms (e.g., France, Germany, Switzerland, Sweden, and the countries of the UK). Political institutions and their normal functioning constrain and direct policy (Paton, 1990).

The field of policy studies also analyzes how different policy communities and networks (both insider and outsider) influence policy. Even in an era of globalization and (in particular) global capitalism, ‘‘global policy debates arrive at local conclusions.’’ This observation was made by political scientist Hugh Hedo in commenting on a book by Scott Greer (2004), which explores how – even within the United Kingdom – territorial politics and local policy advocacy after devolution have produced diversity within the UK’s National Health Services. This is such that one can now talk about four distinctive NHSs (England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland).

To make an analogous observation, a rational approach to policy analysis may seek to combine (for example) universalism, comprehensiveness, and prepayment (whether by tax or insurance) in different ways. In the abstract, there may be little to choose, for example, between a rationally designed NHS and a rationally designed social insurance system.

Yet the proof of the pudding is in the political digestion. How viable a system is in practice depends not just on technical factors such as efficiency (which are rarely only technical, in any case), but also upon how the politics of both policy design and policy implementation play out. It could be argued, for example, that England’s confused and overloaded health reform agenda is destabilizing its NHS, unlike, say, in Finland. Or that France’s social insurance system is being adapted to reap the benefits of an NHS-type system. Globalization constrains, but policy and implementation are affected by politics and political structures. As a result, whether or not a system is viable in the global era depends upon practice as well as theory. For example, is an NHS capable of spending money efficiently and effectively enough to make the requisite taxation rates for a comprehensive service viable? The answer, in theory, is yes. The answer, in practice, is we do not know until we have examined if and how different policy objectives, and policy strands, are rendered compatible (Paton, 2006).

The Politics of Health Policy in the World Today

In order to analyze health policy, it is necessary to analyze politics in health, a better phrase than the politics of health. That is, while there may be certain respects in which the politics of health is unique to health, it is generally true that the effect of general political factors upon health, healthcare systems, and the delivery of health care is more significant. In other words, political economy (both national and international), political structures, and political systems condition health-care systems and indeed the prospects for health.

Control and conflict over resources for both health and health care put health at the center of politics. Consider also the role of the state. Moran (1999) has talked of the health-care state, with echoes of the welfare state, and the implication both that the state affects health care (and health) and that health-care systems in turn affect the state and political life more generally. The traditional concerns of political science – ranging from normative political theory (concerning the nature of the good society and the role of the state) to both analytical political theory and public administration analyzing the nature of, distribution, uses, and consequences of power – are fairly and squarely replicated in analyzing the field of health and health care.

Political history is also important. The twentieth century saw the expansion of health systems, often (especially in the developed world, including the communist block, but also in much of South America) into universal systems (i.e., open to all) if not always fully comprehensive (i.e., covering people for everything). (The United States was a notable exception.) This in itself reflected the politics of the twentieth century in which (from a Western perspective) laissez-faire gave way to the interventionism of either social democracy or at least increased government activism. While this may seem like a characterization of the developed world, in the developing world, the expansion of schemes of health insurance in South America and the export to colonies and ex-colonies in Africa and Asia of health-care systems from the developed world make it a broader picture.

Health Sector Reform

The logic of globalization has been transmitted directly to the world of health policy (even if the detail that emerges is politically conditioned). For example, a think tank of leading businessmen from multinational corporations in Europe in the mid-1980s, setting out just this rationale (Warner, 1994), had as one of its members a certain Dekker, from the Phillips group in the Netherlands, who also chaired the Dutch health reform committee leading to the Dekker plan of 1987 (which was partially implemented over the 1990s albeit in a restricted form).

The Dutch model of managed competition became the prototype for reform of Bismarckian social insurance schemes in Europe and beyond (including South America), as well as for the failed Clinton Plan in the US (Paton, 1996). The UK model of internal markets and purchaser/provider splits in tax-funded health systems became the prototype for reform of NHS and government systems both in developed and developing worlds. It was devised by right-wing political advisers and politicians who advocated commercialization in the public sector. This model (shared with health sector reform in New Zealand) even became the prototype, somewhat incredibly, for health system reform in the poorest countries of Asia and Africa. Later in the 1990s and early 2000s, the World Bank sought to broaden the framework by which reform ideas and criteria were assessed, but the watchwords were still competition, market forces, and privatization.

The World Health Organization has sought a broader basis for evaluating (and therefore, implicitly, exporting) health system reform. The WHO (2000b) has sought to evaluate health systems around the world by a variety of criteria, including quality, cost-effectiveness, acceptability to citizens, and good governance. The World Bank’s approach, as stated, is heavily influenced by the neoliberal economic agenda applied to health and welfare, an agenda itself influenced by public choice theory (Dunleavy, 1989), especially purchaser/provider splits between buyers and sellers of health services, managed competition, and quasi-commercial providers.

The assumption is that publicly funded health care has to be delivered more efficiently, or cheaply, and has to be more carefully targeted. In Western countries such as the Netherlands, the latter could be done by advocating publicly funded universal access for a restricted basket of services (i.e., universality but not comprehensiveness).

In the developing world from the 1980s onward, usually under the aegis of multilateral agencies such as the World Bank and bilateral aid departments such as Britain’s Overseas Development Administration (which became the Department for International Development in 1997), Western policies promoting market forces in health care have been advocated and partially implemented. In other developing countries, the watchword has been decentralization, but the political intention has frequently been both to limit the role of the state in health care and to make communities more responsible for their own health (which sounds culturally progressive but is likely to be fiscally regressive).

As for the whole world, the key question for developing countries is: How is better health (care) to be financed? The options range from private payment through private insurance, through community self-help or cooperative activity, through public insurance, to national systems financed from government revenues, whether operated from the political center or from devolved, decentralized or deconcentrated agencies. (The last refers to field agencies of the central government.) In developing countries, the infrastructure for modern tax-based or national insurance systems often does not exist.

Moreover, the decline of tax and spend in the developing as well as developed world means that third-way solutions (meaning neither traditional state or fully public services nor unregulated markets) are also sought in the third world, irrespective of the names or slogans used. In health, the poorest countries have focused upon building social capital (as in the West): Communities, with aid from bilateral and multilateral agencies as well as nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), have sought to create mutual or cooperative local (informed) insurance schemes.

The priorities for investment in health are often set through a mixture of expert-based needs assessment and local choice via rapid appraisal of local people’s needs. Not surprisingly, this offer leads to a focus upon the key determinants of public health such as sanitation, immunization, reproductive and sexual health (embracing maternal and child health), and so on.

Regarding access to more expensive and acute or secondary health services, the key issues are the availability of pharmaceuticals at affordable prices (with both state and market solutions such as parallel imports being attempted); the provision of integrated primary and secondary care, often through actually siting primary care facilities at hospitals; and the charging policy of public hospitals (i.e., should they be free, should they implement user charges, and if so, how can equity be protected?).

Politics is important in all of these areas. For example, if the private sector in hospital provision is encouraged, it may undermine public hospitals’ ability to raise revenue from user charges for better-off patients.

The Changing Capitalist State and Health System Reform

Paradoxically, the capacity of the health-care state (Paton et al., 2000) is increasing in proportion to the complexity of social regulation, while the state’s autonomy from economic interests is diminishing. Either the new managerialism (i.e., business systems to replace public administration (Exworthy and Halford, 1999) or direct politicization of public sector targets (Paton, 2006)) is used is to seek to tailor health services to both economist needs and economically filtered social needs. Use of the central state to extract maximum additional surplus value for private business from health-care provision can reach its apotheosis in the NHS model. Two paradoxes therefore arise. Firstly, the most progressive and egalitarian model for health services (the NHS model) is also the most easily subverted. (The central state can be used and abused.) Secondly, where the NHS model is off the political agenda (as in the United States) because of a pro-business ideology, the surrogate policy for taming health care in the interests of business (i.e., managed care) is much less cost-effective.

Consider the hypothesis that state-funded health services (such as the NHS) are a cheap means of investment in the workforce and the economy. If firms derive extra profit (surplus value) as a result of healthier workers that is due to social spending, then that extra profit can be thought of as the total extra income minus the costs of the social spending (e.g., corporate tax used to contribute to the NHS) that firms make. The residual – the extra profit – is composed of two elements: The contribution that workers make to their own health-care costs and social expenses (e.g., through tax), which increases their productivity and firms’ profits; and the exploitation, i.e., surplus value extracted from, for example, health-care workers. This latter element, if it exists, derives from the incomes of health-care workers being less than the value they create, i.e., the classic Marxist definition of surplus value.

It might be objected that governments do not plot such a scenario or situation. But sociopolitical pressures help to produce such an underlying reality. The changing socioeconomic structure of Western societies, and the international class structure produced under global capitalism, leads to pressures on publicly financed health systems. This is inter alia because more inequality and more complex differentiation of social structures leads to different ability and willingness to pay tax and/or progressive social contributions on the part of different strata. Either private financing of (say) health care will increase or public services will have to please affluent consumers and satisfy corporate expectations for their employees, as well as investing in health on behalf of the economy’s needs. The latter may not be equitable, if equity means equal access to services on the basis of equal need. Put bluntly, health-care consumption demands by the richer and investment in the health of skilled, scarce employees, will conflict with egalitarianism in health services.

Greater social inequality plus the absence of a left-of-center electoral majority thus puts pressure on egalitarian policy and institutions such as an NHS available to all irrespective of ability to pay. Attempts to defend such a service tend to be forced onto the terrain of economic justifications, to the argument that international competitive advantage requires a healthy workforce. But the workforce is not the same as the whole of society. Nor is a post-Fordist workforce (i.e., a national class structure shaped by international capitalism) an undifferentiated structure: Some workers are more equal than others when it comes to prioritizing health for economic reasons. It is here that arguments about social capital are sometimes used: A healthy workforce requires a healthy civil society. But this in turn may be a zero-sum game between regions and communities.

At this point, it is worth bringing in the classic Marxist dispute about the nature of the state: Is it a (crude) committee of the bourgeoisie and does it manage the long-term viability of capitalism; or is it an area of hegemonic struggle. In health and health care, what would the rational capitalist state do?

If the state is the rationalizing executive board of the capitalist class, one can imagine the board’s secret minutes saying, it makes economic sense for us for the state to fund and provide health care. That way, we will pay less than if we directly provide health benefits for our workforce, company by company or industry by industry. It makes sense because taxation is less progressive than it used to be (so workers pay more; we pay less); the state can force hospitals and other providers to do more for less, i.e., exploit the health workforce to produce additional surplus value for most of us; and the said public services can invest in the productive using allegedly technocratic means of rationing.

At this point, however, if the country’s health-care providers were private, for-profit concerns, they might object, on the grounds that the broader interests of (the majority of) capitalists went against their interests, namely, to derive as much profit as possible from a generously funded health system (broadly, the U.S. position). Equally corporate insurers in the United States resist a single payer or statist model. Note that such a situation does not pertain in the United Kingdom, with the commercial sector in health care being less economically and therefore politically salient and essentially content with marginal income from the NHS (important as that is in its own terms). Additionally, leaving investment in the workforce to individual firms means a system whereby there is a problem of collective action: Firms will not do it for fear of simply fattening up workers who then move to another firm; or rather, they will only do it in order to recruit and retain the most valuable workers. Again, this is broadly the U.S. situation.

On the other hand, if the state finances and provides a common basket of health services for all (the European model), mechanisms will have to be put in place to limit that basket and to increase productivity in its production. This will mean that wider benefits will be sought privately by individuals or employers. This, very broadly, is the agenda driving European health system reform.

If the state is more than a committee of capitalists (whether with or without the health-care industry) then ironically the hard-nosed longer-term agenda of competitiveness may be easier to implement; hence the continuing viability of the British NHS on economic as opposed to ethical lines, rather than the messy and expensive U.S. system. (Note how New Labour – in defending the NHS – points to how European social insurance taxes business directly.)

The choice between state health care to promote selective investment rather than equitable consumption is glossed over in the rhetoric of the third way, whereby the former becomes social investment and the latter is downplayed either as old tax and spend or as failing adequately to emphasize health promotion, and so on.

Overall, the state in the developed world balances the claims of individual firms, the overall capitalist system and particular laborist or welfarist claims. But in today’s international capitalism, securing inward investment is the crucial imperative. Health policy is not determined by political economy, but it is influenced and constrained by it. This occurs in two ways: It affects the money available and its distribution, and policy regimes (associated with regimes in political economy) influence governments and policy makers, with policy transfer across ministries.

Conclusion

This article has defined and explored public policy, applying general concepts to ensure that health policy is not treated in too exceptional or parochial a manner. It has gone on to explore some of the complexities in making (and understanding) policy and in implementation.

Policy analysis can be defined in two ways. The first is the systematic but normative examination of situations and options in order to generate choice of policy. The second is the academic analysis of how policies originate and where they come from; who and what shapes them; how power is exerted; and what the consequences or outcomes are.

There is often confusion between those two domains both in theory and in practice, perhaps based on the fact that the two meanings are linked psychologically if not logically. Analysts and advocates who wish to find an analytical basis for policy choice (first domain) often have a subconscious picture of the policy process as rational. That is, they assume there is some basis through which evidence can create consensus as a direction or a decision.

Yet the reality is often that interests, ideologies, or both determine policy choice. These choices (by individuals, groups, or classes) may be rational in that the means are chosen (the policies) for the ends or goals. It is just that there is no scientific basis for adjudicating among ends, especially now that teleologies such as Marxism do not hold sway and would-be universal values such as capitalist liberalism are revealed to be partisan rather than universal.

That is, health policy, like public policy generally, is made as a result of the interplay of powerful actors influencing politicians to make decisions (politics), on the basis of policies that are available and currently salient, either because they are trendy or because they are seen as convenient solutions to those problems that currently dominate agendas. Rationality, in the sense of evidence-based tailoring of means to ends, is only consensual if the key decision makers agree as to ends. This may occur if there is wide and genuine social consensus, or – a very different state of affairs – if those who disagree are excluded from a powerful role in the policy process.

In health policy, as in other spheres, we see – locally, nationally, and globally – that orthodoxies wax and wane over decades. (For example, in what used to be called Western countries, the era of public administration gave way to the new public management in the 1980s, 1990s, and beyond, with the latter subsequently being influenced in a harder market direction by both globalization per se and the mission of supranational block such as the European Union.) We may call these orthodoxies policy regimes. They are regimes because they combine elements of the dominant political economy and the (usually related) current political orthodoxies i.e., they are more than just a policy yet less than an evidence-based certainty.

Bibliography:

- Aglietta M (1979) The Theory of Capitalist Regulation. London: New Left Books.

- Allison G (1971) Essence of Decision. Boston, MA: Little, Brown.

- Altenstetter C and Bjorkman J (eds.) (1997) Health Policy Reform, National Variations and Globalization. London: Macmillan.

- Archer M (2000) Being Human: The Problem of Agency. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Arts W and Gelissen J (2002) Three worlds of welfare capitalism or more? A state of the art report. Journal of European Social Policy 12: 137–158.

- Bachrach P and Baratz M (1970) Power and Poverty. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Bell D (1960) The End of Ideology. Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

- Blas E (2005) 1990–2000: A Decade of Health Sector Reform in Developing Countries. Go? teborg, Sweden: Nordic School of Public Health.

- Buse K, Mays N, and Walt G (2005) Making Health Policy. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press.

- Cawson A (1986) Corporatism and Political Theory. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell.

- Cohen G (1978) Karl Marx’s Theory of History: A Defence. Oxford, UK: Clarendon.

- Cohen M, March JG, and Olsen JP (1972) A garbage can model for rational choice. Administrative Science Quarterly 1: 1–25.

- Crenson M (1971) The Un-politics of Air Pollution. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Dahl R (1980) Dilemmas of Pluralist Democracy. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Day P and Klein R (1987) Accountabilities. Five Public Services. London: Tavistock.

- Dowding K (1990) Power and Rational Choice. London: Edward Elgar.

- Dowding K (1995) Model or metaphor? A critical review of the policy networks approach. Political Studies XLIII: 136–158.

- Dunleavy P (1989) Democracy, Bureaucracy and Public Choice. London: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

- Exworthy M and Halford A (eds.) (1999) Professionals and the New Managerialism in the Public Sector. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press.

- Greer S (2004) Territorial Politics and Health Policy. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

- Greer S (2007) The UK Department of Health: From Whitehall to Department to Delivery to What?. London: Nuffield Trust.

- Hann A (1995) Sharpening up Sabatier. Politics 15: 19–26.

- Heidenheimer A, Heclo H, Adams C, et al. (1975) Comparing Public Policy. London: Macmillan.

- Hill M(1997) The Policy Process in the Modern State. London: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

- Hood C and Scott C (2000) Regulating Government in a ‘Managerial’ Age: Towards a Cross-National Perspective. London: Centre for Analysis of Risk and Regulation, London School of Economics.

- Jessop B (2002) The Future of the Capitalist State. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

- John P (1999) Analysing Public Policy. London: Pinter.

- King A (1973) Ideas, institutions and the policies of governments. British Journal of Political Science 3: 291–313.

- Kingdon J (1984) Agendas, Alternatives and Public Policies. Boston, MA: Little, Brown.

- Klein R (1990) The State and the Profession: The Politics of the Double Bed. British Medical Journal 301: 700–702.

- Le Grand J (2003) Motivation, Agency and Public Policy. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Lukes S (1974) Power: A Radical View. London: Macmillan.

- Mann T and Ornstein NJ (1995) Intensive Care: How Congress Shapes Health Policy. Washington, DC: Brookings Institute.

- Marsh D (ed.) (1998) Comparing Policy Networks. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press.

- Martinussen J (1994) Samfund, stat og marked. Copenhagen, Denmark: Mellemfolkeligt Samvirke.

- Maxwell R (1982) Health and Wealth. London: Kings Fund.

- Moran M (1999) Governing the Health Care State. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

- Navarro V (1978) Class Struggle, the State and Medicine. London: Martin Robertson.

- Osborne D and Gaebler T (1993) Reinventing Government. New York: Plume.

- Paton C (1990) US Health Politics : Public Policy and Political Theory. Aldershot, UK: Avebury.

- Paton C (1996) The Clinton Plan. In: Bailey C, Cain B, Peele G, and Peters BG (eds.) Developments in American Politics. London: Macmillan.

- Paton C (2005a) Open Letter to Patricia Hewitt. Health Service Journal, pp. 21. May 19.

- Paton C (2005b) The State of the Health Care System. In: Dawson S and Sausman C (eds.) Future Health Organisations and Systems. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave.

- Paton C (2006) New Labour’s State of Health: Political Economy, Public Policy and the NHS. Aldershot, UK: Avebury.

- Paton C (2007) Visible hand or invisible fist? Choice in the English NHS. Journal of Health Economics, Policy and Law 2(3).

- Paton C, Birch K, Hunt K, et al. (1998) Competition and Planning in the NHS, The Consequences of the Reforms. 2nd edn. Cheltenham, UK: Stanley Thornes.

- Paton C, et al. (2000) The Impact ofMarket Forces Upon Health Systems. Dublin, Ireland: European Health Management Association.

- Peck J and Coyle M (2002) Literary Terms and Criticism. London: Palgrave.

- Saltman R, Busse R, and Mossialos E (eds.) (2002) Regulating Entrepreneurial Behaviour in European Health Care Systems. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press.

- Schattschneider EE (1995) The Semi-Sovereign People: A Realist’s View of Democracy. London: Holt.

- Segall M (2000) From co-operation to competition in national health systems – and back? Impact on professional ethics and quality of care. International Journal of Health Planning and Management 15: 61–79.

- Stoker G (ed.) (2000) The New Politics of Local Governance. London: Macmillan.

- Taylor-Gooby P (1985) Public Opinion, Ideology and State Welfare. London: Routledge.

- Warner M (1994) In: Lee K (ed.) Health Care Systems: Can They Deliver? Keele, UK: Keele University Press.

- Wilensky H (1974) The Welfare State and Equality. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- World Health Organization (2000a) The World Health Report. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization (2000b) The World Health Report 2000 Health Systems: Improving Performance. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.