A total of 7.6 million children and 287 000 mothers (2010 data) die every year, and approximately 95% of these deaths occurred in 75 countries with the highest burden of maternal and child deaths. Of these, more than two-thirds could be avoided if everyone had access to known effective interventions. Making such interventions available is not just a matter of supplying a drug or vaccine; to ensure effective delivery of interventions, health systems need to be strengthened at all levels, from the community up to the national level.

Economists investigating how health systems can be strengthened in lowand middle-income countries have explored a myriad of issues. This article addresses three core questions:

- How are health services financed?

- What payment methods are used to purchase health services?

- Who are the health service providers?

In each case the concern is to establish the evidence and discuss the implications of current arrangements for efficiency and equity.

There is very active debate on some key policy issues relating to reform of financing, payment, and provision. The second part of this article addresses some of the most contentious issues, notably:

- The appropriate mix of financing sources as countries seek to expand financial protection and move toward universal coverage of health care.

- The role and impact of development assistance for health (DAH) in low- and middle-income countries.

- The desirability of incentive-based payments to health service users and health care providers.

- The role of private sector agencies in health system arrangements (insurance, payment, and provision).

In addressing all low- and middle-income countries, this article considers a very wide range of country circumstances. Health systems differ greatly across low- and middle-income countries, influenced not only by the level of national income but also by countries’ colonial history (British, French, Dutch, etc.), political orientation post-independence, degree of openness to market forces both historically and up to the present, income distribution (existence of high income groups with considerable purchasing power), and of course health conditions. To avoid implying that one pattern fits all, it is crucial to recognize this diversity and its implications for appropriate solutions to the many challenging issues facing health systems in these countries.

How Are Health Services Financed?

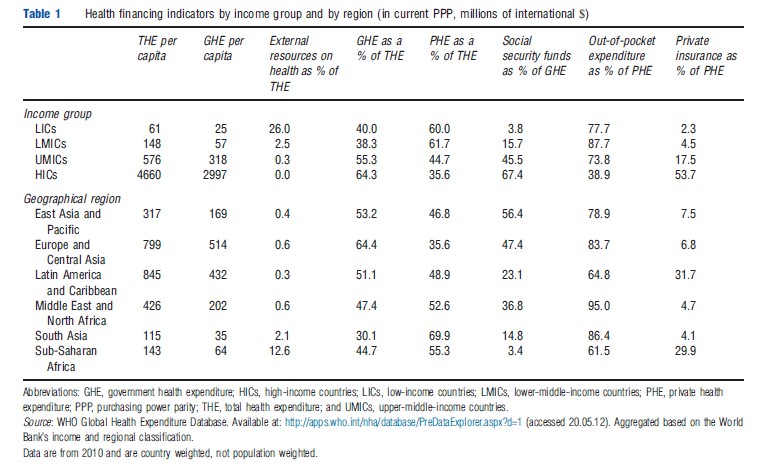

In general, health services in low- and middle-income countries are financed at a much lower level than in high-income countries, and smaller proportion of the total flows through organized sources (i.e., government and insurance intermediaries). Table 1 summarizes health expenditure per capita and the pattern of financing sources and agents by income group and geographical region.

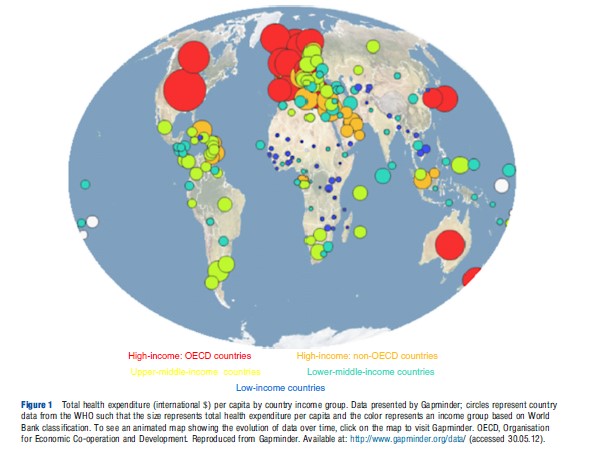

The larger a country’s economy, the more it spends on health – high-income countries spend on average US$4660 on health per person compared to US$356 in lower and uppermiddle-income countries combined and US$61 in low-income countries. The level of health expenditure per capita thus mirrors gross national income per capita and the evolution over time can be displayed on Gapminder. Although spending more on health does not necessarily lead to improved health outcomes, a minimum amount of financial resources is required by a health system to deliver essential interventions. It is estimated that spending of US$60 per capita is needed by 2015 for low-income countries to provide the basic package of essential services required to reach the health-related Millennium Development Goals and strengthen underlying health systems. At present, 15 of the 35 low-income countries spend less than the 2015 mark on all health care, and all but two of these countries (Bangladesh and Afghanistan) are located in Sub-Saharan Africa. These figures highlight the challenges faced by low-income countries, particularly those in Africa, in financing essential services for their citizens.

Lower levels of health expenditure are combined with relatively low shares of financing pooled across population groups, indicative of a lack of organized financing arrangements. Low- and middle-income countries usually lack an adequate tax base or large formal employment sector and/or have weaker infrastructure and management capability; some are also suffering from conflict or are in the midst of a political transition such that they have a weak or nonfunctioning state. In contrast, financing agencies in high-income countries are better established, typically following a model where services are funded primarily from general tax or compulsory social insurance. Some middle-income countries have been more successful than others in expanding pooling arrangements: for example, in East Asia and Europe, social security makes up 56% and 47%, respectively, of general government health expenditure. This particularly reflects China, Indonesia, Philippines, and Vietnam where social health insurance is mandated and countries of the former Soviet Republics, which developed social insurance schemes following independence.

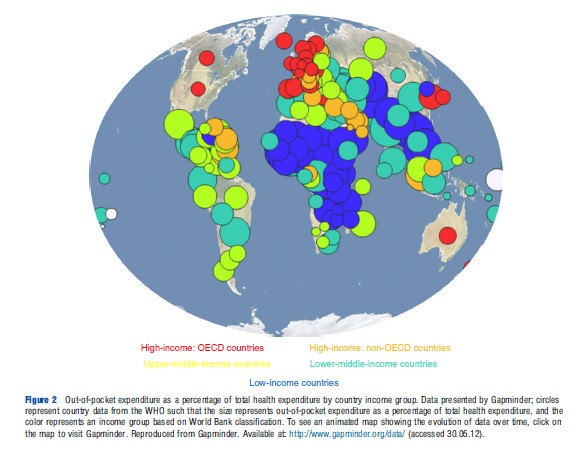

The counterpart to relatively low levels of pooling is that countries rely more heavily on private health expenditures, especially paid out of pocket. Figure 2 shows this reliance to be especially high in low-income countries and in the Sub-Saharan Africa region, and this pattern is also evident over time as displayed in time series data presented in Gapminder. Indeed, private expenditures make up 60% of total spending in low-income countries (compared to 36% in high-income countries) and, within this, out-of-pocket payments represent the majority (i.e., 78% of private health expenditures) and therefore almost half of total health expenditure (Figure 2). High levels of outof-pocket payments reflect the lack of government ability to collect taxes and provide accessible and good quality health care. Some low-income countries rely heavily on external resources to supplement public financing with donors on average contributing more than a quarter of total health spending in low-income countries. Such high reliance on external funding raises concerns for sustainability of services should these contributions decrease, as well as many other concerns discussed in the Section Development Assistance for Health.

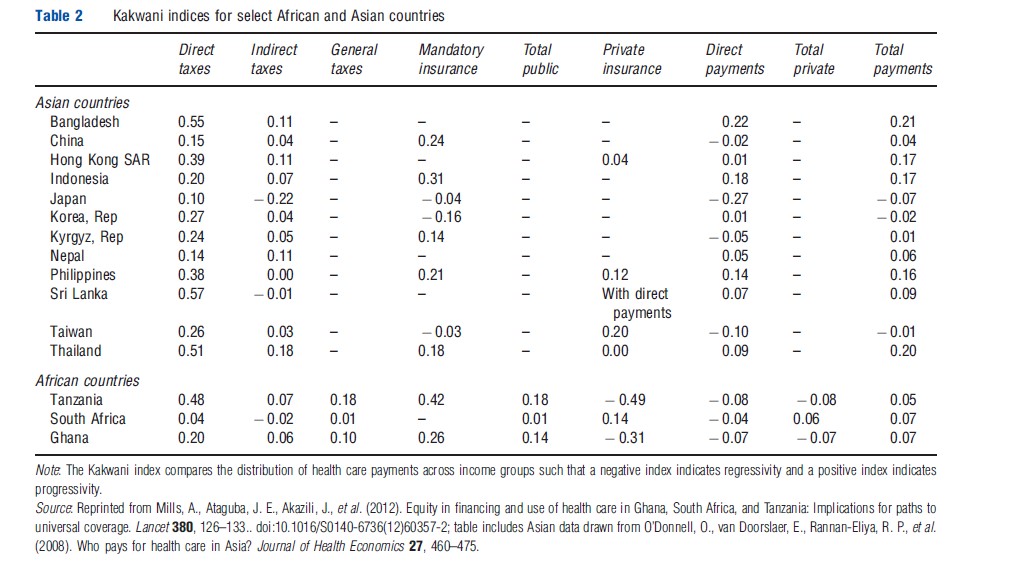

A common criticism of financing patterns in low and middle-income countries is that financing incidence is regressive – i.e., payments for health care weigh more heavily on lower income households. Recent studies have shed light on this question and are summarized in Table 2.

The mix of health financing sources varies substantially across countries, so it is important to consider the incidence of not only overall health care financing but also the main sources: the incidence of a specific type of tax can vary considerably depending on its design and the country context. For example, indirect taxes (e.g., value-added tax (VAT), fuel levies, and excise duties) are regressive in South Africa but progressive in Ghana and Tanzania, a difference likely be explained by the fact that a larger proportion of the South African population are able to purchase goods and services liable to VAT. In addition, although mandatory insurance is progressive in most countries, it is slightly regressive in the three Asian countries studied with universal insurance systems (i.e., Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan). However, such indices need to be interpreted carefully as in systems with less than universal coverage, the progressive insurance schemes may cover only a select population group composed of formal workers or those who are less poor.

Much of the discussion around appropriate financing mechanisms revolves around the need to protect households from catastrophic payments (i.e., levels of expenditures that are high relative to the amount of resources available to the household to pay for their basic needs, which World Health Organization (WHO) defines catastrophic expenditure as equal to or greater than 40% of nonsubsistence spending). The consequences of lack of financial protection against the costs of health care are abundant. Households may forego expenditures on other necessities such as food, clothing, or education, or they may borrow money or sell valuable household assets in order to pay for health services. They may also choose to simply not seek care at all, potentially exacerbating their illness and risking further adverse effects on their earnings. Catastrophic payments can occur in countries at all levels of economic development, but the incidence is higher where out-of-pocket payments are more than 15% of total health expenditures. Households in 18 low and middle-income countries are therefore at especially higher risk of facing such costs, and up to 5% of households in those countries’ risk being pushed into poverty by health care payments.

Low- and middle-income countries thus face major challenges in financing adequate health services and providing financial protection against catastrophic costs. Characterized by low levels of expenditure, fragmentation, and a reliance on out-of-pocket payments, the financing systems suffer from inequities and inefficiencies. Low- and middle-income countries need to expand forms of prepaid financing and reduce fragmentation in the flow and pooling of funds. Doing so will improve equity by cross-subsidizing risks between the rich and poor and the healthy and sick. It will further increase efficiency by decreasing administrative costs and duplicated coordination efforts required for multiple channels and pools.

However, the equity and efficiency of health financing systems are determined also by many other factors affecting both supply and demand. For example, the low status of women may affect their ability to leave the house to seek care; households may not be aware of the benefits of health care; local health services may lack drugs and qualified health workers or be staffed by health workers who are rarely present or who treat patients with disrespect. Equity and efficiency in financing health services further depend on how funds are used to pay for services and providers – issues covered in the following Sections How are Health Services Paid for? and Who are the Health Service Providers?.

How Are Health Services Paid For?

Countries have a choice in deciding how to pay for health services and providers. These choices involve deciding how funding should be channeled from various funding pools (e.g., revenue generated by tax, insurance premiums, and DAH) and payments from individual payers to service providers. There are three principal methods for doing this:

- In relation to inputs (e.g., number of beds, facilities, staff, and items of service).

- In relation to services or outputs (e.g., outpatient numbers and inpatient cases or days).

- In relation to need (e.g., standardized mortality rates).

The payment method used tends to depend on the source of finance. Public funds have traditionally been allocated through hierarchical management structures down to the local service delivery level and are frequently influenced by previous allocations, service or facility volumes and norms, capital developments and associated recurrent expenditure needs, and political influences. Such payment methods tend to assume the historical level of service inputs and outputs is optimal, or at least still appropriate, and does not especially consider efficiency or equity goals. Arrangements may be very inefficient as when more services are purchased than needed, or very fragmented, as in Indonesia where there are multiple channels through which funding flows to the district level. They may also be considered inequitable in that they may not adequately consider health needs, local costs, or income distribution of the recipients for those services.

Following the adoption of similar approaches in richer countries, many low and middle-income countries have sought to introduce approaches that are population- and/or needs based. For example, Brazil, India, South Africa, India, Thailand, and Nigeria have all sought to improve equity in the allocation of public funds (including the health sector) across geographical areas through resource allocation formulae, which account for provincial variances in factors such as population, socioeconomic status, income levels, health needs, and/or membership in insurance schemes. Such approaches recognize that health services are geographically specific and purchasing should therefore be to some extent decentralized. These approaches are still evolving and commonly struggle to overcome both political influences and historical imbalances in the geographical distribution of the capital stock and related inputs. In Thailand, for example, there was a short-lived experiment with per capita allocation of total Ministry of Health funding; subsequently the salary element was removed and allocate separately, thus severely limiting the ability of the funding mechanism to improve inequality in the distribution of health workers.

Within the public health system, health providers are normally salaried and hospitals allocated an annual budget. More recently, contracts that link payments to the performance of health providers or facilities are increasingly found in the public sector and increasingly used to buy the services of private providers or facilities. These approaches, often termed ‘results-based financing,’ aim to increase efficiency in the purchasing of services, equity in access to priority services, and quality of service delivery, but evidence of their performance is sparse. Such issues are discussed further in the section Key Issues.

Insurance agencies (whether public or private) normally pay for health services using activity-related measures such as fee-for-service and case payment. The risk, especially with fee-for-service payment, is that it encourages an unnecessary expansion in the volume of services and a subsequent increase in expenditure. For example, the fee-for-service payment system has been associated with a rapid increase in expenditure in Thailand (for the Civil Service Medical Benefit Scheme), South Africa (for private insurers), and Taiwan and South Korea (both associated with the implementation of universal health care coverage based on social health insurance). Such cost inflation has encouraged the introduction of payment methods, which do better at containing increases in expenditure. In 2002, the South Korean health system introduced a voluntary prospective payment method for inpatient care based on diagnosis-related groups, resulting in costs of care decreasing by an average of 8.3% in participating health facilities. Reform of the payment system, however, has not been comprehensive as plans to mandate the method were prevented by physician opposition. Thailand, in contrast, drawing on its own experience as well as that of other countries in the region, has had a very successful experience of payment reform with its universal coverage scheme. This pays for inpatient care based on diagnosis-related groups within a global budget and for outpatient care based on capitation payment. This has been relatively successful in extending financial protection while restraining costs: public health expenditure has increased steadily to compensate for increasing levels of utilization, but so far, the share of gross domestic product going to the health sector has not increased.

Household direct payments for care are made in response to fee schedules of providers. Although publicly levied fees may be quite simple in structure (e.g., a flat registration fee), private fees may be per item, with drugs charged separately and often with quite substantial markups. Indeed, practices in the procurement, prescribing and dispensing, and pricing of medicines account for three of the top ten causes of inefficiency identified by WHO in the 2010 World Health Report. In particular, drug dispensing is a major source of inefficiency when linked to prescribing functions as it can represent a significant source of income for private providers (and even public providers) – unofficial estimates indicate up to a 50% profit from drug charges in Taiwan. In response, some countries have sought to break the link between drug prescribing and provider income, a measure adopted some time ago in the rich world. These reforms have often been vehemently opposed with varying government responses and impact on expenditure. For example, Taiwan’s 2002 reforms to separate purchasing and dispensing functions were met with strong resistance and a series of protests by the medical profession. To facilitate implementation of the policy, exceptions were made (e.g., rights to dispense were granted to clinics with onsite pharmacists). Such concessions dampened the impact on containment of total health expenditure, although it was successful in reducing drug expenditure. South Korea adopted a different, more rigorous approach in its 2000 pharmaceutical payment reform, breaking the link between prescribing and dispensing, removing all financial incentives, and eliminating profits earned by physicians from drugs. In reaction, however, physicians’ fees increased by up to 44% and a greater proportion of brand-name drugs were prescribed.

Different payment methods thus provide different incentives to health providers and their implementation can sometimes have unexpected effects. Countries need to decide which arrangements to use for purchasing health services. These decisions will affect the efficiency, equity, and quality of services provided. For example, fee-for-service can not only promote responsiveness and productivity but also can lead to inefficiency through supplier-induced demand and cost escalation; capitation and case-based payment can promote efficiency and affordability but may be problematic for quality. The performance of payment systems are determined by the incentives set and how much is being paid, what is being paid for, and who is being paid. In addition, in contexts where capacity to monitor is weak and data limited, there is greater risk of fraud and greater difficulty in fine-tuning payment systems to get the desired results.

Who Are The Health Service Providers?

As countries grow richer, a greater share of total health expenditure is publicly financed, as discussed in the Section How are Health Services Financed?, and hence a greater proportion of health care provision is formally organized. The poorer the country, the greater the diversity of types of provider and greater the fragmentation of health services. In general, health service providers can be categorized into seven main groups:

- Government health services for the general public.

- Services run by social health insurance agencies (in countries where they are direct service providers).

- Services run by nongovernment organizations (NGOs) including church organizations.

- Occupational health service providers, both government (e.g., army) and private (e.g., mines and plantations).

- Private for-profit allopathic providers, both individuals and facilities.

- Traditional medicine providers ranging from the more formal (e.g., Ayurveda) to the somewhat less formal (e.g., traditional healers).

- Informal providers such as drug peddlers and unqualified providers (e.g., known as quacks in India).

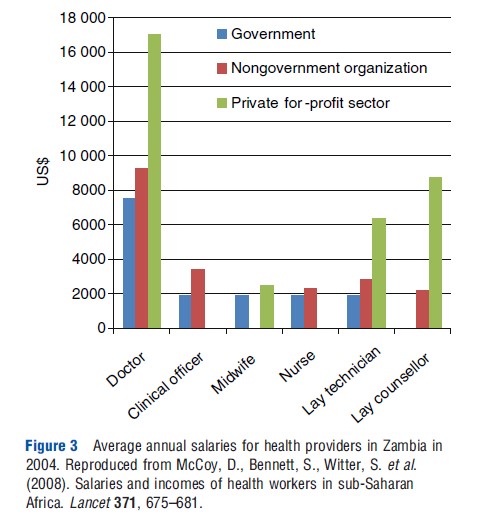

Data on health providers are much more limited than on health financing. In particular, data on private provision are especially scanty, making it difficult to quantify the relative share of public and private provisions. The 2006 World Health Report stated that approximately 70% of physicians and 50% of other health workers cited their employment as within the public sector; however, the report pointed out that the actual distribution in the public sector is likely to be much lower as the data tend to reflect the health worker’s primary employer rather than their main source of income, which in low- and middle-income countries can be significantly higher in the private sector. Evidence on health worker income from Ethiopia and Zambia underscores that the private sector offers much higher remuneration than in the public sector (Figure 3).

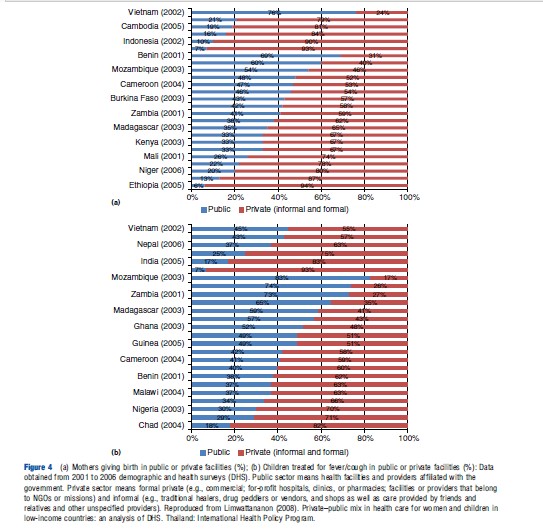

Data on utilization patterns can provide additional information on public and private health service providers. Figures 4(a) and (b) show the relative importance of the two sectors in providing health care to women and children in 25 low-income countries. Although there were high levels of variation across individual countries, the use of public health service providers more than half of the time was reported in only four of the countries for deliveries and in only seven of the countries for child fever/cough. In general, adults, especially men, tend to use private facilities more than children, and the probability of using public facilities is higher for inpatient than outpatient care. For example, other cross-country analyses have found that public hospitals account for 73% of inpatient stays in 39 low- and lower-middle-income countries.

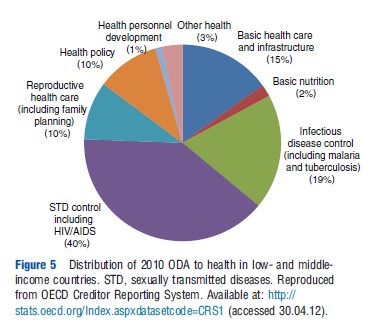

The distribution of health expenditures can also give an indication of balance of service provision. With regards to the level of care, hospitals account for approximately 60% of government health expenditures with tertiary hospitals absorbing as much as 45–69%. Such high levels raise efficiency concerns as hospital care tends not to be the most cost-effective when primary care coverage is incomplete. Indeed, inappropriate hospital admissions and excessive lengths of stay, as well as inappropriate hospital size, represent two of WHO’s top 10 sources of health care inefficiency. The distribution of Official Development Assistance (ODA) for health indicates the priorities of donors: 40% of 2010 ODA disbursement went to providing HIV care and 19% to controlling infectious diseases with only 15% to basic health care and infrastructure (Figure 5).

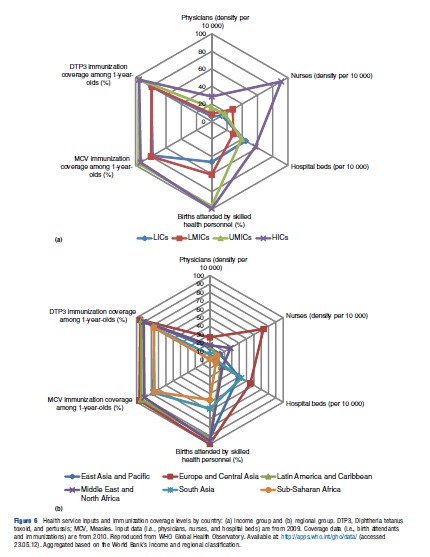

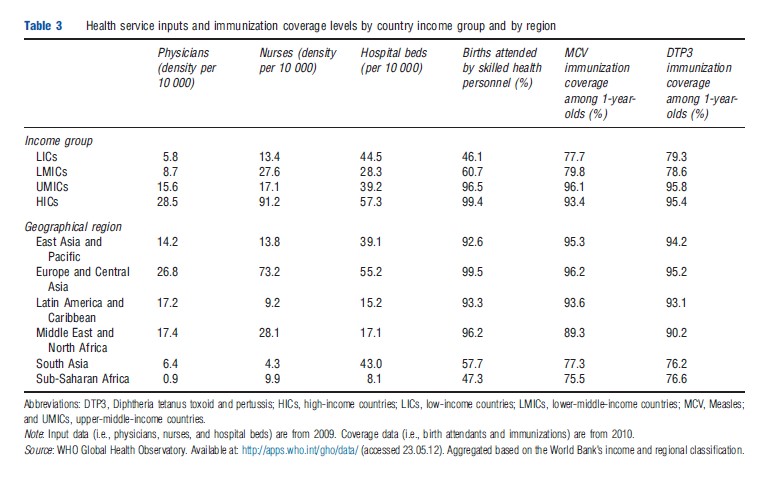

Table 3 and Figures 6(a) and (b) provide data on various other dimensions of health service provision across income groups and regions. These show the relative lack of available service inputs and much lower coverage rates of essential interventions in low- and lower-middle-income countries – all of which carry implications for the equity and efficiency of service provision in developing countries. For example, low-income countries have five times fewer physicians per 10 000 individuals and approximately 50% fewer births attended by skilled health personnel and 16% lower coverage of child immunizations when compared to high-income countries. At the regional level, Sub-Saharan Africa has 30 times fewer physicians per 10 000 individuals and approximately 45% fewer births attended by skilled health personnel and 19% lower coverage of child immunizations when compared to Europe and Central Asia. The health worker shortage in these countries means the insufficient number of providers cannot adequately deliver the care needed in countries with major disease burdens. In the public sector, the mix of doctors and nurses and ratio of health providers to patients are suboptimal, with health workers frequently facing an overwhelming workload and hence delivering low quality of care. It is often for these reasons that the poor seek care in private facilities, which tend to be better staffed and provide more responsive care but often at a higher cost and not necessarily greater effectiveness.

There has been a long-standing debate over the relative efficiency of public and private providers, with claims that private providers are more efficient. However, evidence to support this is scanty and suffers from difficulties in standardizing for type of patients and service models. For example, a study of the provision of primary care in South Africa by various forms of providers (i.e., public clinics, private general practitioners (GPs) contracted to provide free care for poor patients, private GPs practicing privately, a private clinic chain, and company clinic) found that two of the private sector models were delivering services at comparable cost to the public sector – the contracted GP model and clinic chain. However, the two other private sector models (i.e., independent GPs and company clinic) were delivering services at much higher cost, demonstrating the importance of examining the private sector model by model. Contextual influences, such as payment methods, practice styles, and traditions, also affect performance. Regardless of the type of ownership, investing resources in more efficient providers can result in substantial savings and a great potential to provide more health services within a fixed budget. In Namibia, savings from reducing hospital inefficiency could construct 50 clinics and, in South Africa, represent three times the value of user fee revenue.

Another major deficiency is strong evidence on the quality of health services. However, evidence is sufficient to confirm that quality in both public and private sectors is poor, with the private sector tending to perform better in drug availability and aspects of delivery of care, including responsiveness and effort, and possibly being more client orientated. In the case of the South African study referred to above, public clinics tended to offer better technical quality of care than private facilities, but quality as perceived by users was lower due to more crowded facilities and less responsive staff. But there is enormous variation. Many countries, for example, include at one end of the spectrum public and private hospitals offering care of international levels of quality, whereas at the other end of the spectrum are unlicensed and unqualified providers selling drugs, which should be prescription only. Arrangements may be agreed between hospitals and diagnostic laboratories, for example, to refer patients in return for a fee, and regulators may not be independent of the facilities they regulate.

There has been persistent criticism that the use of public services in low- and middle-income countries is inequitable, in that richer groups benefit more than poorer groups. A recent in-depth study of benefit incidence (and financing incidence) in Ghana, South Africa, and Tanzania confirmed this with respect to Ghana and South Africa, although public sector and faith-based organizations’ health service benefits in Tanzania were more evenly distributed across the population. Inclusion of private sector services in this benefit incidence analysis showed even greater disparities in the distribution of benefits. Overall, health services benefited higher income groups despite the greater health needs of lower income groups. The key reasons constraining the access of poorer groups were problems in relation to the availability, affordability, and acceptability of services, particularly health care costs, transport costs, drug stock-outs, insufficient staff numbers, and poor staff attitudes. Such barriers need to be addressed to change the distribution of health services and move toward greater financial protection.

Key Issues

Financing Sources For Universal Coverage

Over the last few years, there has been growing momentum to expand financial protection and set universal coverage as a long-term goal. Evidence has been accumulating from countries such as Thailand that given willingness of governments to support the health care costs of the less well off and design features that constrain cost inflation, universal coverage of a benefit package of reasonable size is possible even for a lower middle-income country. For example, Thailand achieved universal coverage in 2001 (at a per capita income of US$1900) by introducing a new scheme funded from general taxation to cover the 47 million people who fell outside the preexisting schemes for formal sector workers. Vietnam, Philippines, and Indonesia have now adopted universal coverage as a goal with a timetable for achievement. Both South Africa and India are actively debating plans for universal coverage.

It is clear that a mix of financing sources is needed for progress to be made toward universal coverage – general tax revenues are needed for those too poor to contribute; social health insurance arrangements are of value for enrolling formal sector workers; some degree of contributions from user fees is probably inevitable because even with offer of services free at the point of use, some people will still choose to purchase their care from the private sector. The critical question, over which there is considerable disagreement, is whether those in the informal sector who are not the poorest – often a very substantial number of people – should be covered by general tax funding or enrollment in contributory schemes (with or without government subsidy). Thailand, for example, has chosen general tax funding; Philippines and Indonesia have chosen to seek to extend their social health insurance scheme on a voluntary basis to encompass the informal sector; China has rolled out a massive and highly subsidized rural voluntary insurance scheme covering 835 million people by 2011. Key issues are willingness for the share of government funding to health to increase and the feasibility and management costs of encouraging a high proportion of the target population to enroll voluntarily. The latter concerns have led to a plan in Ghana, where a national health insurance scheme was introduced including voluntary enrollment into district insurance schemes, to move to a ‘one time premium,’ a largely nominal payment, thus recognizing the de facto situation that the great majority of funding for universal coverage is coming from direct and indirect taxes.

Development Assistance For Health

As shown in the Section How are Health Services Financed?, DAH is a substantial source of health financing in low-income countries – reaching more than a quarter of total health spending. Trend analysis further shows that the total amount of DAH has substantially increased over the last two decades, from an estimated US$5.8 billion in 1990 to US$27.7 billion in 2011 (in 2009 US$). DAH can have a number of economic consequences as well as political implications.

Development assistance has been criticized for fostering donor dependency and hindering economic growth in recipient countries. Indeed, a high reliance on external funding for health raises concerns over the ability of the government to deliver basic health services. Should these contributions decrease – and some recent estimates are showing a decreasing rate of growth of DAH flows since the global financial crisis – it would threaten the delivery of essential health care. Any gap in health financing would need to be covered by the government or private funding. In low- and middle-income country settings, where there are institutional, economic, and fiscal constraints hampering significant government funding increases, the outcome would most likely be higher out-of-pocket payments, further restricting access to health services by the poor.

However, development assistance has also been promoted as a means to empower countries to lead their own development by providing opportunities for strengthening the role of the state and for economic growth. Development assistance can help to build basic health infrastructure, especially in underserved areas or post conflict settings, which can be a visible and important indicator of a functioning state. It may also stimulate improved sector-level policies and strategies, especially when development assistance is channeled through mechanisms such as Sector-Wide Approaches (SWAps).

There has been controversy over whether DAH displaces domestic spending on health. A recent statistical analysis of expenditure data over the period 1995–2006 suggested that for every US$1 of DAH to governments, there was a decrease in government health expenditures by US$0.43–1.14. The analysis further found that when DAH was given to the nongovernmental sector, government health expenditures increased by US$0.58–1.72. However, the evidence for displacement is still inconclusive, not least because of data limitations. Data at the country level, especially in low-income countries, are often missing and estimates frequently vary across institutions (e.g., the degree of correlation between the WHO and International Monetary Fund estimates for government health expenditure is only 65%). In addition, the probability and extent of displacement is likely to vary greatly across countries. For example, in response to increases in DAH, the Democratic Republic of Congo appears to have decreased its domestic health spending by more than 30%, whereas its neighbor, the Central African Republic, increased spending by more than 30%. Factors specific to individual countries, such as donor behavior and domestic policy choices, are likely to be influential. Thus, firm conclusions cannot be drawn, and it is imperative to understand not only whether such effects are occurring but also why. Moreover, the debate underlines the need to understand broader issues such as how domestic spending responds to the volume and type of development assistance.

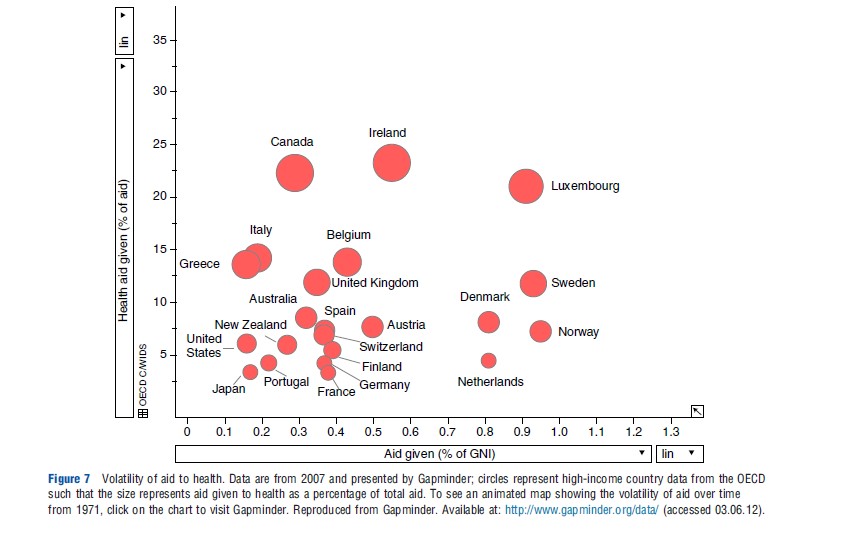

Additional issues relate to other aspects of the effectiveness of aid. There has been very long-standing concern that health aid flows through far too many channels, is fragmented and excessively tied to specific short-term projects rather than longer term programs and strategies, and is unpredictable. For example, the change in flows of funds from 1 year to the next can create difficulties in implementing sustainable health programs in recipient countries. The volatility in aid given to health over time is shown in time series data presented by Gapminder (hyperlink embedded in Figure 7). Furthermore, the individual reporting requirements of numerous development partners put pressure on already weak financing systems in recipient countries. All of these concerns are reflected in harmonization and alignment principles agreed in the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness and subsequent Accra Agenda for Action. However, much remains to be done. For example, the proportion of ODA to maternal, newborn, and child health, which flows to projects (rather than sector-wide support, for example), has consistently stayed approximately 90% over the 2003–10 period. Various joint donor funding arrangements have sought to coordinate donor support, but many funding flows remain outside coordination mechanisms.

Results-Based Financing To Users And Providers

Results-based financing has recently attracted much attention as a way of implementing agreed priorities through stimulating demand, purchasing services, and encouraging improved health worker productivity and service quality. It is defined as ‘a national-level tool for increasing the quantity and quality of health services used or provided based on cash or in-kind payments to providers, payers, and consumers after predetermined health results (outputs or outcomes) have been achieved’ (https://www.rbfhealth.org/). It is a generic term for a number of different approaches, including:

- Provision of vouchers to enable individuals or households to obtain health care.

- Payment of cash to households conditional on use of specific services and other sorts of financial transfers, for example, to cover transport cost.

- Payment of financial incentives to providers (individual health workers, facilities, or organizations) to supply certain types of services or reach certain quantity or quality targets.

- Agreeing contracts for services with associated performance targets.

- Output-based aid where provision of aid is conditional on achievement of certain targets, such as a minimum immunization coverage level.

Interest in such approaches has grown rapidly over the last few years, with dedicated funding for such projects being provided by the World Bank and bilateral aid agencies. Results-based financing has been introduced in a number of developing countries, particularly in the Latin America and South Asia regions, and frequently for maternal and child health interventions. Although positive results have been reported in several schemes, reliable evidence on effectiveness, especially in low-income countries, is still fairly sparse. There is a gap in understanding how such mechanisms can improve performance and what are the necessary factors to ensure intended effects, and there is virtually no evidence on the cost-effectiveness of such approaches relative to other ways of improving provision of services and increasing the uptake of health care.

Proponents of results-based financing point to available evidence suggesting that such incentives have positively influenced various levels of the system – recipients of health care (individuals and households), providers of health care and facilities, as well as resulted in positive outcomes including higher coverage of key interventions, better service quality, increased efficiency, and/or improved health outcomes. Rwanda has often been cited as an example for its pay-for-performance scheme, and reports often identify increases in uptake of maternal and child health interventions. However, results-based financing may also increase inequities and produce undesirable effects (e.g., reducing the intrinsic motivation of health workers, gaming, cherry picking, neglect of other activities, and corruption). The effectiveness of performance contracts with the private sector has also been questioned as, while there is evidence they have improved access to services, little is known about its impact on the equity, efficiency, and quality of care of the wider health system. Finally, output-based aid can not only accelerate achievement of health targets but has also been criticized for being too narrow and short term in focus. The varied results are a function of the range of results-based financing instruments, their individual design, and implementation in diverse country contexts. Scheme design should be based on an understanding of the underlying problems the scheme is intended to address and on the country context (e.g., taking into account local managerial capacity), and performance indicators must be aligned with the goals of the health system. The impact of results-based financing also depends critically on the ability to implement the scheme effectively and monitor performance.

More broadly, results-based financing is not only argued to improve accountability (allowing for regular reviews of performance) and increase equity (in targeting certain population groups) and efficiency (in improving performance) but it also raises questions over the degree of involvement of donors in scheme initiation, design and implementation, and the sustainability of such arrangements beyond the initial donor funding.

The Role Of Private Sector Agencies

Concern about the capacity and performance of governments in both low and middle-income countries has led to considerable interest in how private sector agencies may perform some roles traditionally assigned to the state. Such roles may include:

- The provision of private insurance.

- The administration of insurance arrangements on behalf of the state.

- The management of drug distribution systems and other elements of public health service management.

- The provision of services.

Debates about private insurance mirror those in high-income countries – namely that it is likely to be neither an efficient nor equitable way of providing financial protection to significant numbers of people. Moreover, there are few countries, which have any sizeable private health insurance sector, given the very limited market of those who can afford to pay. The main potential role is to provide additional cover, to relieve the public health system of the pressure to cater for the highest income group.

A different role for private insurers is to administer state sponsored financing arrangements. For example in India, the Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana scheme, launched in 2008, targets households below the poverty line. Parastatal and private insurers bid to administer the scheme, which involves receiving a fixed sum of public money per household recruited to the scheme, providing them with a smart card, which is both the evidence of membership and records health care costs up to the allowable maximum per year, signing up hospitals to provide care, and managing payment arrangements. There is annual retendering of the contract, with competition focusing on the fixed sum per household that is requested. This design has permitted very rapid roll out of the scheme across India, with 40 million people covered by 2012. Concerns have focused on low rates of utilization of care by members in some states (hence increasing the profits for the company), fraudulent claims by providers, and in some states incremental creep year by year in the capitation sum.

The management strengths in the private sector have also been drawn on in other areas of health system management. For example, South Africa, which has some considerable private sector capacity, has experience of contracting out drug distribution to hospitals and clinics and also of contracting a private company to manage public hospitals. Evaluations of such arrangements have identified issues similar to those found in high-income countries – the challenges of managing the principal–agent relationship; difficulties of specifying contracts for clinical care; and difficulties public agencies can face in managing contracts well.

Private agencies can play two main roles in service provision. Private providers can directly be contracted to provide services on behalf of the state. Most experience of this model comes from contracts with NGOs, both the international NGOs and indigenous ones, and there is evidence that NGOs working under contract and managing district services have increased service delivery in underserved areas. A second approach is to use a variety of means to improve the quality and reduce the cost of the less formal part of the private sector that is extensively used by poorer groups. Approaches such as accreditation of clinics, franchizing outlets to provide contraception and sexually transmitted diseases treatment, and training of drug sellers can work successfully, although experience is very varied and most approaches have been tried only on a very small scale.

Effective engagement with the private sector is important, but a strong public primary care system has been shown to be critical in bringing health services to communities and improving health outcomes. For example, the experiences of Ethiopia and Bangladesh in investing in human resources and innovative delivery methods in the public system have resulted in wide reaching and effective primary health care systems.

Conclusions

This article has covered a very wide canvas in terms of both countries and issues. Echoes are apparent with many of the issues facing high-income countries – the best mix of financing sources, role of out-of-pocket payments, best ways to pay providers, desirability of incentive-based arrangements, and relative roles of public and private sectors. However, the context of low and middle-income countries means that policy lessons from high-income countries do not necessarily transfer well to all low- and middle-income country settings. Key features that affect the relevance of policies include the very widespread poverty; high proportion of the population in the informal sector; relative weakness of political; and social institutions including governance structures; limited management capacity in the public sector, and vulnerability to influence by agencies external to the country. Numerous studies show that the detailed ways in which policy reforms are designed and implemented in particular contexts play a key role in how they perform, alerting us to the need to be wary of seeking global solutions to health system challenges.

References:

- Berendes, S., Heywood, P., Oliver, S. and Garner, P. (2011). Quality of private and public ambulatory health care in low and middle income countries: Systematic review of comparative studies. PLoS Medicine 8, e1000433, doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000433.

- Gottret, P. and Schieber, G. (2006a). Financing health in low-income countries. In Gottret, P. and Schieber, G. (eds.) Health financing revisited: A practioner’s guide, pp. 209–248. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Gottret, P. and Schieber, G. (2006b). Financing health in middle-income countries. In Gottret, P. and Schieber, G. (eds.) Health financing revisited: A practioner’s guide, pp. 249–278. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Goudge, J., Russell, S., Gilson, L., Molyneux, C. and Hanson, K. (2009). Household experiences of ill-health and risk protection mechanisms. Journal of International Development 21, 159–168.

- Kalk, A. (2011). The costs of performance-based financing. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 89, 319.

- Lu, C., Schneider, M. T., Gubbins, P., et al. (2010). Public financing of health in developing countries: A cross-national systematic analysis. Lancet 375, 1375–1387, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60233-4.

- Meessen, B., Soucat, A. and Sekabaraga, S. (2011). Performance-based financing: Just a donor fad or a catalyst towards comprehensive health-care reform? Bulletin of the World Health Organization 89, 153–156.

- Mills, A., Ataguba, J. E., Akazili, J., et al. (2012). Equity in financing and use of health care in Ghana, South Africa, and Tanzania: Implications for paths to universal coverage. Lancet 380, 126–133, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60357-2.

- Mills, A. J. and Ranson, M. K. (2005). The design of health systems. In Merson, M. H., Black, R. E. and Mills, A. J. (eds.) International public health: Diseases, programs, systems and policies, 2nd ed., pp. 515–558. Boston: Jones and Bartlett Publishers.

- Ooms, G., Decoster, K., Miti, K., et al. (2010). Crowding out: Are relations between international health aid and government health funding too complex to be captured in averages only? Lancet 375, 1403–1405.

- Tangcharoensathien, V., Patcharanarumol, W., Ir, P., et al. (2011). Health-financing reforms in Southeast Asia: Challenges in achieving universal coverage. Lancet 377, 863–873.

- WHO (2010). The World health report: Health systems financing. The Path to Universal Coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Xu, K., Evans, D. B., Kawabata, K., et al. (2003). Household catastrophic expenditure: A multicountry analysis. Lancet 362, 111–117, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13861-5.

- https://www.gapminder.org/data/ Gapminder.

- https://apps.who.int/nha/database WHO Global Health Expenditure Database.

- https://www.who.int/data/gho WHO Global Health Observatory.