Few subjects are more important to public health than food. One of the major ways in which humans interact with their environment is through our food. The science of nutrition has developed through the study of the components of foods that are required to sustain life and to maintain health. Improper diet can cause disease if important nutrients are missing from the diet, and inappropriate dietary practices can increase the risk of certain diseases.

Essential nutrients are substances that must be in the human diet to support life. These essential nutrients include vitamins, inorganic elements, essential amino acids, essential fatty acids, and a source of energy, and water. A lack of a nutrient or an insufficient amount of a nutrient can result in a deficiency disease that can be life threatening in extreme cases. The essential nutrients are widely distributed in foods and most people can obtain sufficient amounts of them if they consume a varied diet.

Elements Of Human Nutrition

Energy

Most of the food consumed is used by the body to supply energy. The body is able to digest and absorb into the blood stream components of carbohydrates, fats, and protein that can be metabolized by the body to release energy. Energy is used to maintain body temperature, support metabolic processes, and to support physical activity. People are generally in a state of energy balance, that is, they consume as much energy as they use to support their bodies and daily living. They tend to gain weight if they are in positive energy balance, or lose weight if they take in less than they expend. Most excess energy is stored by the body as fat. Energy needs are usually expressed in kilocalories, but in much of the world’s scientific literature, energy expenditure is expressed in joules or kilojoules (1 kilocalorie equals 4.184 kilojoules).

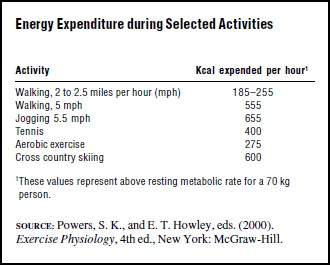

The energy expended by the body when at rest is quite constant between individuals and can be estimated quite closely by prediction equations that take into account age, sex, and body weight. The resting metabolic weight of a 70-kilogram (154-lb.) man, for example, is estimated to be 1750 kilocalories per day, and for a 58-kilogram (128- lb.) woman, 1350 kilocalories per day. The total daily energy needs are related to the amount of physical activity expended in the course of everyday life. A person whose life style involves light amounts of activity may have a total energy expenditure of about one and one-half times their resting metabolic rate, while a person who is engaged in very intense physical activity may expend over twice as much energy as their resting metabolic rate in the course of twenty-four hours. Exercise can increase the metabolic rate considerably, depending on the type and duration of the activity. The amount of energy expended by certain types of physical activity is shown in Table 1.

Table 1

Protein

The principal structural components of body soft tissues are proteins, which are made by the body from amino acids. The amino acids along with the nucleic acids are the principle nitrogen-containing components of the body and of most foods. The enzymes that regulate most body processes are also proteins. The body can synthesize many of the amino acids needed for protein syntheses, but some amino acids must be obtained from the proteins in the diet. The dietary essential amino acids for humans are threonine, valine, leucine, isoleucine, methionine, lysine, histidine, and tryptophan. Two others can only be formed from essential amino acids: tryosine from phenylalanine, and cystine from methionine. Human dietary protein requirements are quite modest. An adult man of average weight is estimated to need about sixty-three grams of protein per day, while an average woman is estimated to need about fifty grams. The protein must supply the essential amino acids required by humans and sufficient total nitrogen to allow syntheses of the other amino acids required for protein synthesis.

Fats

Fats are synthesized from carbohydrates, but the body is unable to make certain fatty acids, which are components of fats. These essential fatty acids, notably linoleic and linolenic acid, must be supplied by dietary fats. Fats that are solid at room temperature, such as butter or lard, usually contain high amounts of saturated fatty acids such as palmitic or stearic acid. Fats that are liquid at room temperature such as vegetable oils are higher in unsaturated fatty acids, which include oleic acid as well as the linoleic and linolenic acid. Fat is the most concentrated source of energy available to humans, supplying about nine kilocalories per gram of dietary fat, compared to four kilocalories per gram of carbohydrate and protein. Fat is also the principal storage form of energy in the body.

Vitamins

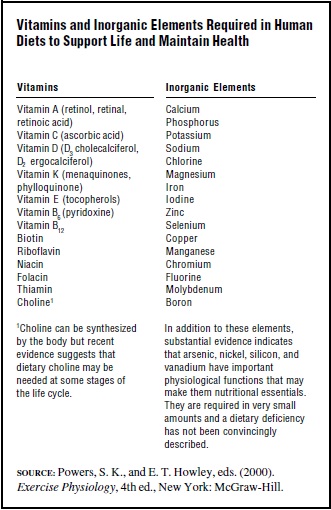

Vitamins are a diverse group of dietary essentials that have important functions in the body. The vitamins known to be required by humans are listed in Table 2. Many of them are components of co-enzymes, molecules that are required for some enzymes to carry out certain metabolic processes. Others, such as vitamin E and vitamin C, act as antioxidants, protecting body components from damage from oxygen needed by the body for metabolism. Some are more like hormones, such as vitamin D, which regulates the absorption of calcium from the intestine and the formation of bones. Vitamin D can actually be formed by the action of ultraviolet light from the sun on vitamin D precursors found in the skin, but since this synthesis may not be sufficient at times, humans need a dietary source of vitamin D. Vitamin A is a component of visual pigments in the eye that respond to light stimuli and are essential for sight.

Table 2

A deficiency of a vitamin may result in a characteristic deficiency disease related to the body function affected by the lack of the vitamin. Vitamin D deficiency can cause soft bones in children, a condition called rickets; vitamin A deficiency may cause night blindness and even blindness in its more severe form. Many of the vitamins have multiple functions in the body, and deficiency diseases can be severely debilitating in severe cases. Vitamins are required in very small amounts by the body. Only a few micrograms of vitamin B12 is required each day, while vitamin C requirements may be from sixty to one hundred milligrams per day.

Inorganic elements

Humans also require several inorganic elements as components of the diet. The inorganic elements known to be required by humans are listed in Table 2. These elements may have a structural function, such as calcium and phosphorus, which are needed for bone synthesis, or they may have a catalytic function similar to some of the vitamins. They are required for the action of many enzymes in the body. Sodium and potassium are essential for fluid balance. Iodine is an essential component of thyroxin, the hormone produced by the thyroid gland. Some of the inorganic elements are required in extremely small quantities, only micrograms per day, while other elements may be needed in higher amounts. Soils vary in their content of some of the trace elements, and plants grown in some areas may be deficient in an essential element. This has been true for iodine, where a deficiency is still observed in many areas of the world, and selenium, where geographically based human deficiency disease has been observed.

Nutrition Recommendations

In the United States, the National Academy of Sciences, through the National Research Council and The Institute of Medicine, has convened expert groups since 1941 to establish nutrition recommendations to be used by individuals and institutions for planning nutritionally adequate diets. These groups have established recommended dietary allowances (RDAs) as the daily dietary intake level for a specific nutrient that is sufficient to meet the nutritional requirements of nearly all (97–98 percent) individuals in the life stage and gender group specified. In the most recent recommendations, dietary reference intakes (DRIs) have been specified that have attempted to estimate average nutrient requirements, RDAs, and an upper limit of safe nutrient intake. Where data are not sufficient to set a precise RDA, new recommendations called adequate intake (AI) define a recommendation for some nutrients.

The RDAs and AIs are used to plan diets for groups in hospitals, the military, large institutions, to set standards for government food programs such as school lunches, to establish nutritional labeling, and for counseling individuals. Similar dietary recommendations have been made by expert groups convened in many countries and also by international organizations such as the World Health Organization and the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. These recommendations are periodically revised to include information from most recent research findings. The latest recommendations for dietary reference intakes can be obtained in the United States from the National Academy Press, 2101 Constitution Avenue, NW, Washington, D.C. 20418.

Recommendations have been established for most nutrients where sufficient research data are available to make reliable estimates. The nutrient recommendations are given for different age groups and are differentiated by sexes because of different nutritional needs at different stages of life. Infants and young children who are growing rapidly have different nutrient needs compared to adults. Women who are menstruating need more iron to replace blood lost in the menstruation compared to postmenopausal women or men. Similarly, there are special needs for pregnant and lactating women. There is increasing evidence accumulating about the needs of the elderly, and nutrition recommendations now include a category for individuals over seventy years of age.

Recent revisions of nutrition recommendations have taken into account public health concerns about osteoporosis, a condition in which bone mineral is lost and older individuals become more vulnerable to bone fractures. New recommendations stress the importance of maintaining a high level (1200 mg/day) of calcium intake by both men and women over fifty years of age in an attempt to reduce loss of bone mineral. Similarly, recommendations for folic acid intake have also been revised to stress the importance of sufficient folic acid consumption by women who may become pregnant. Insufficient folic acid has been associated with a higher incidence of birth defects. The concern for adequate intake of folic acid led to the fortification of enriched grain products with folic acid in the United States beginning in 1998.

Nutrient recommendations also take into consideration the efficiency by which nutrients are digested and absorbed from foods. The form in which iron is ingested has a major influence on how much food iron is absorbed into the body. Iron in animal products is well absorbed because it is found as a component of hemoglobin or muscle pigments, while iron in plants, found as inorganic salts, is poorly absorbed. Some components of plants, such as phytic acid and tannins, also interfere with iron absorption. Therefore, dietary recommendations for iron intake must consider the availability of iron in the foods being consumed.

Public Health Nutrition Issues

In the early part of the twentieth century, nutritional disorders were common. Pellagra, a disease caused by a deficiency of nicotinic acid, was widespread in the southern United States. Rickets, from vitamin D deficiency, was common, and goiters from iodine deficiency were widespread. Iron-deficiency anemia and riboflavin deficiency were frequently observed. In parts of Asia, beriberi, a disease caused by thiamin deficiency, was a public health problem. The discovery and characterization of the vitamins made it possible to produce them in large amounts, and the enrichment of grain products with niacin, riboflavin, thiamine, and iron largely eliminated B-vitamin deficiencies in the United States as a public health problem. Similarly, the addition of vitamins A and D to milk provided protection from deficiency of the nutrients. The use of iodized salt essentially eliminated goiter from the U.S. population.

Unfortunately, nutritional deficiencies have not been eliminated from much of the world even today. A combination of poor diet, poor sanitation, and lack of safe water leading to frequent intestinal infections, causes more than 200 million of the world’s children to be shorter and weigh less than children in good environments at the same age. These malnourished children are often born underweight from mothers who are also underweight and of poor nutritional status. Measures of the degree of malnutrition that are frequently used include a comparison of a child’s weight for age, height for age, and weight for height with norms established by similar measurements on a well-nourished population of children. A usual convention classifies a child whose weight for age is more than two standard deviations below the standard as malnourished, and those three standard deviations below the standard are usually considered severely malnourished. The most vulnerable time for growth faltering in children is the period from six months of age to two years, when breast feeding stops and weaning foods are introduced. A combination of poor weaning foods, exposure to contaminated water, and poor sanitation that results in frequent bouts of diarrhea and the occurrence of other childhood diseases contributes to the poor growth of children after weaning.

The United Nations estimates that more than two-hundred million of the world’s children are stunted, with the largest numbers being found in South Asia and in Africa. Similarly, about 4 percent of the world’s population is considered at risk for iodine deficiency disorders including goiter, cretinism, and mental retardation. Vitamin A deficiency is estimated to affect about 3.3 million children in the world. Iron deficiency anemia is also the most prevalent nutritional deficiency in the world. Over 90 percent of those effected live in developing countries. The United Nations has estimated that severe anemia is a contributing factor to 50 percent of maternal deaths in developing countries.

Nutritional deficiencies are common in the refugees displaced by wars and natural disasters. Assistance is provided by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees to more than 26 million people worldwide, and there are other internally displaced people in the world that may number as many as 31 million. The difficulty of providing food for these displaced groups puts them at risk for nutritional deficiencies.

Nutritional deficiencies are rare in most industrialized nations in Europe, Asia, and the Americas, and among the higher income groups of the developing world. The public health issues related to nutrition in these nations are concerned with over–consumption of energy, inadequate levels of activity, and improper food choices. Dietary practices are known to be risk factors for severe chronic diseases, including hypertension, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, and several types of cancers. The amount and type of fats seem to influence the risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases and to risk of certain forms of cancer. The consumption of saturated fatty acids and trans fatty acids found in certain hydrogenated cooking fats increases the levels of serum total cholesterol and cholesterol associated with serum low density lipoproteins (LDL) and thus increases the risk of artheriosclerosis and coronary heart disease. Diets high in fruits, vegetables, legumes, and cereal products are associated with a lower occurrence of coronary heart disease and certain cancers.

Genetic variations occur among individuals in their response to food. Variations in various blood lipoprotein components can effect an individual’s response to dietary fat and cholesterol, and risk of coronary heart disease. There appears to be a genetic component to susceptibility to obesity. As more information is known about the human genome, it may be possible to predict more accurately individual risks for disease, and the dietary factors that may modify this risk.

Obesity

Dietary patterns that are characterized by the consumption of energy-rich, high-fat foods are considered to be factors contributing to obesity, particularly when the high intake of energy is not accompanied by appropriate physical activity. Obesity in adults is defined by reference to the body mass index (BMI), a relationship that takes into account both height and body weight. The BMI is calculated as weight in kilograms/ height in meters squared. In pounds and inches it is calculated by weight (pounds)/height (inches)2 ? 704.5. A person with a body mass index between 20 to 25 is considered in the normal range, while a body mass index of 25 to 30 is considered overweight, and over 30 is considered obese.

The prevalence of obesity in the United States has increased markedly in recent years. The prevalence of overweight children ages six to eleven in surveys conducted in the early 1970s was 6.5 percent of males and 4.9 percent for females. By 1988–1994, the prevalence of overweight in this age grouping had increased to 11.4 percent and 9.9 percent for males and females respectively. On the basis of surveys carried out between the years 1988 and 1994, more than 50 percent of American adults were considered overweight on the basis of having a BMI greater than 25. In further surveys, 17.9 percent of U.S. adults were considered obese in 1988, compared with 12 percent in 1991. The increasing prevalence of obesity is of considerable public health concern as excess weight is associated with greater risk of mortality, non-insulin dependent Type II diabetes mellitus, hypertension, stroke, osteo-arthritis, and some cancers. The annual number of deaths attributed to obesity in the United States has been estimated at more than 280,000 persons.

The control of obesity is difficult, and weight reduction is difficult to maintain. The most effective weight loss schemes seem to be those that reduce weight slowly, from one-half to one pound per week, and that involve both reduction in energy intake and an increase in physical activity. For overweight individuals, a reduced intake of from 300 to 500 kilocalories per day should result in a loss of one-half to one pound per week, while severely obese individuals may need to reduce energy intake by 500 to 1000 kilocalories per day to achieve a one to two pound per week weight loss.

Dietary guidelines

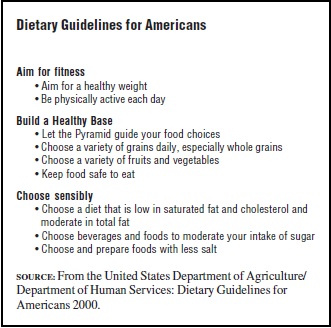

The concern for appropriate food choices have led many countries to issue dietary guidelines that provide advice that goes beyond the recommendations for individual nutrients covered by the recommended dietary allowances. The year 2000 dietary guidelines for Americans are shown in Table 3. These are issued by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and are revised about every five years. This publication represents the only official dietary advice to consumers by the U.S. Government. The full text of the bulletin provides more detailed advice on food choices. Many countries have published similar dietary guidelines to guide food choices to reduce the dietary risk factors associated with chronic disease.

Table 3

To give advice to consumers regarding appropriate food choices to implement dietary guidelines, food guides have been developed. One of the most popular representations of a food guide is the dietary pyramid that has been published by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Department of Human Services. This food guide illustrates the importance of building a healthy diet on a base of cereal-based foods supplemented liberally with fruits and vegetables. Foods high in protein and fat should be consumed sparingly. The pyramid provides the number of recommended daily servings of the food groups.

Food supplies

The world population is projected to increase about 25 percent from the year 2000 to 2020, to about seven and one-half billion people. Most of this increase is projected to be in developing countries located in the tropical zones of the earth. The population of Asia is projected to increase by 800 million, and the population of Africa is projected to double. The International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) has projected that food production will be able to increase such that the world per capita food available will supply about 2,900 kilocalories per person per day in the year 2020, compared to 2,700 kilocalories in 1993. The equitable distribution of food supplies will remain a major problem. The daily food available in sub-Saharan Africa is projected to supply only about 2,300 kilocalories per capita in the year 2020, barely sufficient to support a productive life. IFPRI estimates that one out of every four of the world’s children will be malnourished in the year 2020. To achieve the projected increase in food supplies, continued improvements in crop yields will be necessary.

In contrast to the limited food supplies in many developing nations, developed countries are projected to have a food supply that will provide 3,470 kilocalories per capita per day in the year 2020. The U.S. Department of Agriculture indicates that the available food in the United States in 1994 provided 3,800 kilocalories per capita. This food supply provided annually 193 pounds of red meat, poultry, and fish, 585 pounds of dairy products, 194 pounds of cereal products, 151 pounds of fresh, canned, or dried fruits, 208 pounds of fresh, canned, frozen, dried, or fried vegetables and pulses, and 147 pounds of sugar. These figures represent food availability and do not represent actual consumption or account for wastes and losses in marketing and food preparation. Even with the variety of food available, consumers in the United States do not generally meet the dietary guidelines and food guide recommendations. For example, in food consumption surveys, only 38 percent of those surveyed reported consuming the recommended number of servings per day of cereals, 41 percent of the servings of vegetables (heavily weighted toward potatoes and starchy vegetables), and 23 percent of the servings of fruits. The reported diets provided 33 percent of the energy from fats and 11 percent from saturated fats. Food choices by consumers appear to depend on a variety of factors, such as cost, food preferences, convenience of preparation, and cultural norms, in addition to perception as to effects on health.

Food safety

In addition to providing nutrients, food can also potentially be a source of harm to a consumer. Hazards associated with food include microbiological pathogens, naturally occurring toxins, allergens, intentional and unintentional additives, modified food components, agricultural chemicals, environmental contaminants, and animal drug residues. It has been estimated that more than 80 million cases of food-borne illness occur annually in the United States, resulting in more than 9,000 deaths, primarily from microbiological contamination. The transformation of a safe food into a potentially dangerous one can occur anywhere in a food system that consists of producers, shippers, processors, wholesalers, retailers, and consumers.

An effective food safety system requires regulation, surveillance, consumer education, and continued research to detect and prevent food-borne illnesses. The increase in world trade in food also involves international dimensions in food safety issues. Import regulations dealing with food safety may also have the effect of restricting access to markets, and food safety becomes an issue in world trade.

The United States has a complex system of food-safety regulation. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is responsible for domestic and imported foods in interstate commerce except for poultry and meat products. The FDA has responsibility for standards for food labeling, inspects food-processing plants, and regulates food animal drugs and feed additives and all food additives. The Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) inspects meat and poultry products to ensure they are safe and correctly marked, labeled, and packaged. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) licenses pesticide products and establishes tolerances for pesticide residues in food products and animal feeds. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) are responsible for surveillance of illnesses associated with food consumption in association with the FDA and the USDA. These agencies also collaborate with state and local public health agencies that are concerned with food safety.

The consumption and preparation of food also has great social and cultural significance, contributing to the daily enjoyment of life. Public health concerns about dietary practices often must compete with these values as an individual makes food choices. This makes the issues associated with food and nutrition more complex than the medical and public health issues discussed here.

Bibliography:

- Institute of Medicine, Food and Nutrition Board (1989). Diet and Health: Implications for Reducing Chronic Disease. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

- Institute of Medicine, Food and Nutrition Board (1997). Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium, Phosphorous, Magnesium, Vitamin D, and Fluoride. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

- Institute of Medicine, Food and Nutrition Board (1997). Dietary Reference Intakes: Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6 , Folate, Vitamin B12 , Pantothenic Acid, Biotin, and Choline. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

- Institute of Medicine, National Research Council (1998). Ensuring Safe Food. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

- Mokdad, H. H.; Serdula, M. K.; Dietz, W. H.; Bowman, B. A.; Marks, J. S.; and Koplan, J. P. (1999). “The Spread of the Obesity Epidemic in the United States 1991–1998.” Journal of the American Medical Association 282:1519–1522.

- Must, A.; Spadano, J.; Coakley, A.; Field, E.; Colditz, G.; and Dietz, W. H. (1999). “The Disease Burden Associated with Overweight and Obesity.” Journal of American Medical Association 282:1523–1529.

- National Research Council, Food and Nutrition Board (1989). Recommended Dietary Allowances, 10th edition. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

- Pandya-Lorch, R.; Andersen, P. P.; and Rosegrant, M. (1997). The World Food Situation: Recent Developments, Emerging Issues, and Long Term Prospects. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Shils, M. E.; Olson, J. A.; and Shike, M. (1994). Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease, Vols. 1 and 2, 8th edition. Philadelphia, PA: Lea and Febiger.

- Shils, M. E.; Olson, J. A.; and Shike, M. (1999). Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease, 9th edition. Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins.

- Stipanuk, M. (2000). Biochemical and Physiological Aspects of Human Nutrition. Philadelphia, PA: W. B. Saunders Company.

- Sub-Committee on Nutrition (ACCI/SCN) United Nations Administrative Committee on Coordination (1997). Third Report on the World Nutrition Situation. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Triano, R. P., and Flegal, K. M. (1998). “Overweight Children and Adolescents: Description, Epidemiology, and Demographics.” Pediatrics 101:497–503.

- United Kingdom Department of Health (1991). Dietary Reference Values for Food Energy and Nutrients for the United Kingdom: Report of the Panel on Dietary Reference Values of the Committee on Medical Aspects of Food Policy. London: HMSO.

- United States Department of Agriculture and the United States Department of Health and Human Services (2000). Nutrition and Your Health: Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Home and Garden Bulletin no. 232, 5th edition. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office.

- S. Department of Agriculture (1992). The Food Guide Pyramid. Home and Garden Bulletin no. 252. Washington, DC: Human Nutrition Information Service.

- World Health Organization (1985). Energy and Protein Requirements: Report of a Joint FAO/WHO/UNU Expert Consultation. WHO Technical Report Series 724. Geneva: Author.