The first section of this article reviews the risks associated with cross-border trade as well as legal consequences of trade treaties, focusing on World Trade Organization (WTO) agreements. It also discusses three features of the WTO agreements, which provide space for addressing the tensions between the economic objectives of trade policy and public health objectives. The second section of the article reviews how the WTO has been adjudicating disputes which have had health implications; indeed, the WTO dispute settlement mechanism is a venue whose explicit function is to weigh the objectives of facilitating international trade with other objectives included in these same treaties such as the protection and promotion of human health. The article concludes with some illustrations of ongoing exercises of global health diplomacy where tensions between trade and health policy objectives are being negotiated.

How Can Trade Affect Health?

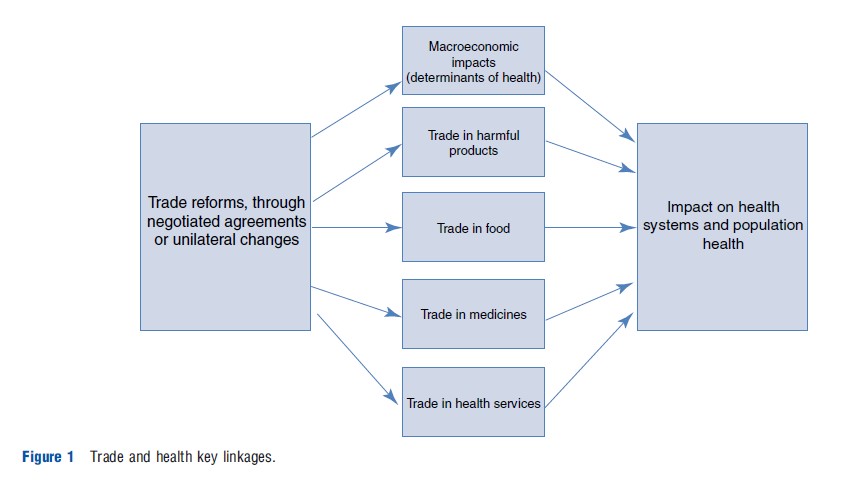

When we examine the impact of trade on health, we are looking at two types of independent variables. First, it can refer to international trade rules as they are embodied in multilateral, regional, and bilateral trade and investment treaties negotiated by national governments. Second, it includes the impact of economic integration, i.e., increased cross-border flows of goods, services, and capital. Trade agreements can increase economic integration and the intensity of these cross-border flows; however, these may take place in the absence of treaties and should be considered as a separate analytical entity. Trade so defined can have impact on health systems and population health through a number of transmission channels. There are five main causal chains (see Figure 1). Trade reforms can have an impact on the macroeconomic conditions of a country to facilitate or hinder population health through changes in characteristics, such as poverty and inequality. Trade reforms can also ease or restrict access to harmful products, such as tobacco, weapons, or toxic waste. Third, trade policy in the agricultural sector can affect population health through its impact on food security, diet, and nutrition. Fourth, trade agreements also influence access to medicines by including patent protection such as we find in the WTO’s Agreement on Trade-related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS). This is the trade-health linkage that has received most attention from academics, policy makers, and civil society organizations in the last 15 years. The final section of the article focuses on a fifth channel, trade in health services.

National health systems can be transformed by the introduction of cross-border suppliers and investors. Trade in health services can take four different forms. First, the services can be provided electronically with both the patients and the providers remaining in their own jurisdictions; telemedicine across border is an example of such a trade. This is called Mode 1 of the General Agreement of Trade in Services (GATS) of the WTO.

Second, patients can travel abroad to receive care; health tourism or medical tourism has received a lot of attention in research and policy circles in recent years. There are good indications that there is a steady increase of health tourism, even though the actual scale is not well measured. Concerns have been raised regarding the quality of care and equity, in terms of the impact of such trade on the health system of the countries to which patients travel. Indeed, health tourism has been presented as an economic opportunity for many middle-income countries that are struggling with relatively weak health systems. The main concern is the risks of reallocation of resources away from local patients toward higher quality care supplied to affluent domestic and foreign patients.

However, Mode 2 trade can become an important source of foreign exchange earnings and add to the multiplier effects of tourism-related activities in the host economy. Promoting health tourism can also lead to efficiency gains for importing countries. According to one estimate, the health care system in the US would save $1.4 bn annually if only one in ten patients were to go abroad for a limited set of 15 highly tradable, low-risk treatments.

Another potential positive contribution is that some of the revenues from health tourism be harnessed to improve access to health care services for the local population. Typically, advocates of health tourism will recommend that governments in developing countries ‘‘put in place universal access policies that require private providers to contribute to a health care fund’’ (Mattoo and Rathintran, 2005). However, a review of the literature and the institutional frameworks related to health tourism failed to identify such a mechanism. Neither in the more established health tourism destinations like India, Jordan, Thailand, nor in countries that are more recently involved in this form of service exports (the Caribbean, Mexico, Costa Rica) has an explicit mechanism to allocate some of the additional income generated from health tourism been used to increase access to health care services for local patients. The only country found to have mentioned a specific tax on health tourism is New Zealand, where the government was considering in 2009 to apply on specific levy on private hospitals catering to foreign patients which would contribute to the Accident Compensation Corporation, a public agency which provides a comprehensive, no-fault injury insurance to all New Zealanders and visitors (reference http://www.imtj.com/ news/EntryId82=166606).

The third mode of cross-border supply of health services according to the GATS relates to the movement of capital, such as foreign investors investing in the establishment or the management of a clinic or a hospital. The potential benefits of Mode 3 trade in health-related services are to generate additional investment in the health care sector, contribute to upgrading health care infrastructure, facilitate employment generation, and provide a broader array of specialized medical services than those available locally. However, the potential downside risks of Mode 3 trade once more include growing inequality in access and the emergence of a two-tiered health care system. This two-tiered system may result from an internal ‘brain drain,’ as foreign commercial ventures may encourage health professionals to migrate from the public to the private health care sector.

Trade in health services can also take place through the temporary movement of natural persons (so-called Mode 4 of the GATS); a nurse, physician, or other health professional practice abroad on a temporary basis. Mode 4 trade is still limited relative to its potential due to a number of regulatory barriers posed by recipient countries. These barriers include immigration rules, discriminatory treatment of foreign providers, and the nonrecognition of foreign qualifications. Virtually all countries impose restrictions on temporary migration and the quotas are usually substantially lower than the actual demand for entry. The cross-border movement of health care professionals may promote the exchange of clinical knowledge among professionals and therefore contribute to upgrading their skills and medical standards. The potential downside risks of Mode 4 trade arise from the danger that such mobility may be of a more permanent nature, such that health care professionals often trained at considerable home country expense are for ever lost, thus reducing the availability and quality of services on offer to home country consumers of health care services.

Trade rules can affect the cross-border supply of health services. Indeed, the main reason national governments agree to sign trade treaties is to increase access to foreign markets and facilitate international trade. Governments make commitments in trade agreements such as GATS, where they guarantee access for foreign investors interested in establishing a new clinic or health insurance company with a view to facilitate and increase cross-border flows of services and capital. Governments can unilaterally adopt reforms where they allow foreign services providers to compete in the domestic markets through one or all of the four modes of supply; however, including this reform into the binding commitments of a trade agreement decrease the likelihood that this policy will be reversed in the future.

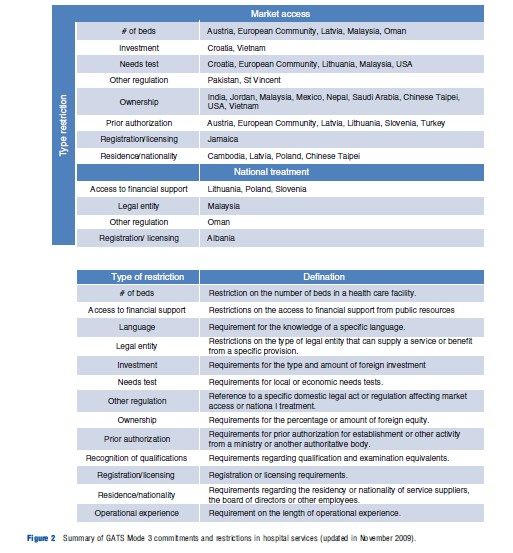

In the case of health-related services, WTO members have made relatively few and limited commitments in the GATS. One can argue that one option for policy makers to address the tensions between trade and health has been to prefer unilateral trade reforms rather than to include liberalization of health-related services into multilateral trade treaties. In that manner, they maintain a greater flexibility to experiment with cross-border health services provision and reverse reforms if they fail to deliver the desired outcomes. The detailed nature of these trade commitments in services provides a second avenue for government to address the tensions between their trade and public health objectives. Indeed, WTO member states can fine-tune their GATS commitments according to which of the four modes and specific health-related services they want to include in their list of commitments. They can also decide whether they want to commit to national treatment (no discrimination against foreign providers vs. domestic ones) or to market access (removing barriers to entry). They can also stipulate specific conditions for entry for foreign providers. For instance, the European Community and Malaysia have stipulated in their commitments that entry of foreign investors in hospital services is subjected to an economic need test and to limits to the number of beds in the hospital (see Figure 2). These provisions can allow health authorities to channel foreign investments in hospitals in regions and of the size required as to their health care system planning.

Given the flexibility built into its design, it can be argued that the GATS provides the margin for maneuver for policy makers to harness the positive impacts of trade in health services, while mitigating the associated risks. However, we should note that other trade agreements do not have the same design and do not offer the same level of flexibility. For instance, governments have become parties to a vast network of investment agreements which aims to offer a predictable environment for foreign investors by protecting them against some kinds of state actions, such as discrimination and expropriation without compensation, and, as a result, to encourage foreign investment. These agreements, whether they are integrated in larger trade agreements or are stand-alone bilateral investment treaties, can exclude some sectors, but they tend to have a broader coverage with fewer exceptions and carve-outs, hence offering less space for addressing potential tensions between trade and health.

A third manner in which tensions between trade and health can be negotiated is at the national level with the adoption of domestic public policies which mitigate the negative impacts and harness the positive consequences. For instance, in Thailand, the increase in health tourism had a negative impact on the human resources for health in the country as nurses and physicians were attracted to work in the large urban hospitals catering to foreign patients, exacerbating the urban–rural gap in terms of access to health care services. To address this problem, the government significantly increased admissions in nursing and medical schools. These ‘flanking’ policies can take many forms, but they all require policy coherence, i.e., national authorities need to make their policy choices and the impacts of these choices explicit, realizing the potential divergence and trade-offs to be made between the realization of economic/trade policy objectives and public health goals, at least in the short term.

How Has The WTO Managed The Tensions Between Trade And Health?

When the agreements of the WTO came into force in 1995, they included a new dispute settlement mechanism which has become, since its creation, a key forum for managing the tensions between trade and health. Indeed, member states of the WTO have brought a number of disputes to the Panel and its Appellate body, which involved measures designed to protect human health, or claiming to do so.

How have these WTO panels and the Appellate body arbitrated disputes where the objectives of trade and the public measures to promote and protect public health clash? First, the WTO has defended the right of national governments to adopt public measures, even if they violate WTO rules, by claiming that these measures were necessary to protect human health under the exception found in General Agreement on

Trade and Tarriffs (GATT) Article XX(b). Thus, when in 1998 Canada challenged France’s ban on asbestos, the Panel estimated that the measure violated the national treatment principle in the GATT (Article III:4) which prevent parties from discriminating foreign products in favor of domestic products. In this case, the Panel judged that the French-made products containing polyvinyl acetate (PVA), cellulose, and glass fibers were similar to foreign products containing asbestos fibers (and therefore were like products as defined by Article III:4 of the GATT). Even though they deemed the measure discriminatory, the Panel agreed that the ban on asbestos was justified, given the health exception in Article XX(b) of the GATT. The Appellate body supported that view but went further and concluded that in determining whether products are similar, health impacts should be considered; hence, considering that products containing asbestos fibers should not be seen as similar to products containing PVA, cellulose, or glass fibers.

The WTO health exception specifies that the measures to protect human health should not be ‘‘applied in a manner which constitutes a means of arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination or a disguised restriction on international trade.’’ In 2007, the WTO concluded that Brazil was applying its ban on import of used tires in a discriminatory manner. The arbitrators did not challenge the right to adopt measures to protect public health, even though they were violating the national treatment principle. In this case, the ban on imports was adopted in order to limit the breeding grounds for diseases-transmitting mosquitoes created by stockpiling of discarded tires. The problem was that Brazil has allowed some imports from South American neighbors, whereas other countries such as the members of the European Union were under the complete import ban.

An earlier case involving an American regulation on gasoline had affirmed the capacity of WTO members to restrict trade to protect human health as long as trade-restricting health measures do not discriminate in violation of the national treatment principle (GATT Article III:4) by treating imported products less favorably than like domestic products. ‘‘Trade-restricting health measures that violate the national treatment principle may still be legitimate under GATT Article XX if such measures (1) fall within one of Article XX’s enumerated exceptions, and (2) are applied in a manner that does not constitute unjustifiable discrimination or a disguised restriction on international trade.’’ (Fidler, forthcoming).

Beyond the health exception, another principle which has been key in guiding WTO arbitrators when they have to manage the tensions between trade rules and public health objectives is the need for scientific risk assessment when adopting a sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measure. Indeed, the SPS Agreement (Article V) requires domestic regulation to be based on a risk assessment which takes into account available scientific evidence. The appropriate level of protection should be determined in consideration of economic factors such as the loss of production, the cost of control or eradication, the cost of alternative approaches, and with a view of minimizing negative trade effects.

The first WTO dispute involving the SPS agreement was initiated in 1996, by the US and Canada who complained that the prohibition enacted by the European Communities (EC) on the importation and sale of meat treated with growth hormones in order to protect human health violated the SPS Agreement. The Panel and the Appellate body agreed with Canada and the US that the EC had violated Article 5.1 of the SPS Agreement and that the evidence presented by the EC’s risk assessment did not support a total ban on meat with growth hormones. The other WTO dispute which related to the SPS agreement, the dispute around the EC de facto moratorium on biotech products such as genetically modified food, did not challenge the European assessment of the risks associated to the products. The European measures were violating procedural requirements of the SPS agreement.

Finally, the TRIPS agreement includes a clause (Article 30) which allows members to adopt policies that contravenes other provisions of the agreement, which has been used in a health related dispute. This exception was tested by the disputes between Canada and the EU on patent protection for pharmaceuticals which began in 1999. With a view to reduce prices and improve access, generic pharmaceutical manufacturers in Canada were allowed to produce a drug under patent without the patent holder’s permission in order to (1) obtain regulatory approval for the generic pharmaceutical product, and (2) produce a stockpile of generic drugs to sell when the patent expired. The government argued that even though these rules were violating some aspects of the TRIPS agreement, they fell within the exceptions provided by Article 30 of TRIPS. The WTO Panel partially agreed with Canada, ruling that allowing stockpiling before the expiration of the patent could not be justified under the public health exception.

Global Health Diplomacy In On-Going Trade Negotiations

Trade negotiations which can have an impact on health systems and population health through the five channels illustrated in Figure 1 are still on-going in a diversity of global and regional contexts. For instance, the European Union has been negotiating economic partnership agreements (EPA) with four regional groups in Africa since 2007. Because the EPAs touch on a wide range of trade-related issues, some have expressed concerns that they can potentially have a negative impact on health in sub-Saharan Africa. Four main areas of concern have been raised in this case: The impact of trade liberalization on public revenues and therefore the public expenditures for health; the risks of increasing patent protection in terms of access to pharmaceutical drugs; the opening of health services to foreign investment; and the impact of agricultural liberalization on food security and poverty.

What are the means of balancing these concerns against the potential economic benefits associated with trade liberalization? One means proposed is the use of health-impact assessments (HIAs) of proposed trade reforms. HIA are a set of procedures for assessing the potential impact of public policies on population health and the distribution of these effects on the population. It has been proposed they can be a useful tool as it can make the linkages between trade and health more visible to policy makers, it can improve the quality of evidence available to them, it can influence how the goals of trade policy are perceived by policy makers, and it can be used by various interest groups as an instrument for advocacy and mobilization. Equipped with the information from an HIA, trade negotiators are better positioned to decide to forgo certain trade commitments, to include some restrictions and limitations on their commitments or again, to adopt domestic policies which will ensure that trade policy does not impede the realization of national health objectives.

Except for the impact of patent protection on access to medicines, the linkages between trade and health are still an underexplored area of research and policy debates. Trade negotiations may be stalled at the WTO, but there are a number of trade and investment treaties being negotiated at the regional and bilateral levels which requires a more explicit approach to address the tensions between trade and health policy objectives.

References:

- Fidler, D. Summary of key GATT and WTO cases with health policy implications. In Blouin, C., Richard S. and Drager N. (eds.) Diagnostic tool on trade and health. Geneva: WHO, forthcoming.

- Mattoo, A. and Rathindran R. (2005) Does health insurance impede trade in health care services? World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, No. 3667, July.

- Blouin, C., Drager, N. and Richard, S. (eds.) (2006). International trade in health services and the GATS: Current issues and debates. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Fairman, D., Diane, C., McClintock, E. and Drager, N. (2012). Negotiating public health in a globalized world: Global health diplomacy in action. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Hopkins, L. R. L., Vivien, R. and Corinne, P. (2010). Medical tourism today: What is the state of existing knowledge? Journal of Public Health Policy 31, 185–198.

- Lee, K., Ingram, A., Lock, K. and McInnes, C. (2007). Bridging health and foreign policy: The role of health impact assessment. Bulletin of the WHO 85, 207–211.

- Pachanee, C. and Wibulpolprasert, S. (2006). Incoherent policies on universal coverage of health insurance and promotion of international trade in health services in Thailand. Health Policy and Planning 21, 310–318.

- World Trade Organisation and World Health Organisation (2002). WTO agreements and public health: A joint study by the WHO and WTO secretariats, Geneva.

- https://www.thelancet.com/series/trade-and-health Lancet on Trade and Health.

- https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/206023 The World Health Organisation.