There has been considerable debate in recent years regarding globalization of health services and its implications for exporting and importing economies. This debate has been sparked by the growing scope for cross border delivery of health services due to advances in information and communication technology, growing mobility of healthcare providers and patients, and commercialization of health services through foreign direct investment (FDI) and entry of domestic private players. Today, trade in health services takes place through telemedicine, medical value travel, cross border flows of healthcare workers, international capital flows, and transnational corporations in the health sector. There are also emerging opportunities in information technology (IT)enabled delivery of health-related services, such as medical coding, transcriptions, and back-office health support services.

In light of growing healthcare challenges confronting governments worldwide due to rising healthcare costs and strained public sector budgets, aging societies, and growing demand-supply gaps in healthcare, globalization of health services is a potentially important means of providing quality healthcare, of ensuring financial sustainability of health systems, and enabling equitable access. However, given the scant and often anecdotal nature of information on trade in health services and lack of primary evidence or case studies, it is difficult to understand the trends and characteristics in any detailed manner or to draw any concrete conclusions regarding the associated risks and challenges. Hence, the debate on the implications of globalization of health services remains polarized, mostly based on conjectures and opinions rather than factual and empirical analysis. One side stresses the potential to benefit from increased foreign exchange earnings with positive implications for the domestic health systems and another side voices concerns regarding the potential adverse effects on equity and access to healthcare.

The discussion in this article focuses on one form of globalization of health services, namely, international capital flows and foreign commercial presence in the provision of health services. It consolidates the scattered, secondary information that is available on such flows in order to outline the broad trends and characteristics of this mode of health services delivery and highlights the perceived, and where available, realized impact of such flows.

The Section on Overview of Trends provides an overview of trends in foreign financing of healthcare services, highlighting key source and recipient countries as well as major firms providing health services across borders through overseas commercial presence. It also discusses the nature of such capital flows. The Section on Policies Governing Foreign Investment in Health Services highlights the regulatory environment affecting foreign investment in health services for a sample of countries. It also compares national policies with multilateral commitments made by selected countries on foreign commercial presence (mode 3) in health services under the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) (the other three modes of supply in health services, under the GATS are: Mode 1 (cross border supply)). The discussion highlights the regulatory and other concerns characterizing the liberalization of health services. The Section on the Impact of Foreign Investment in Health Services discusses the benefits and challenges associated with the movement of capital in health services, drawing on existing studies and discussions with healthcare providers. Given various classification issues and interdependencies between trade in health services and other related services such as insurance, education, and IT-enabled services, the discussion on impact primarily focuses on capital flows in health services establishments such as hospitals, clinics, and diagnostic facilities. The Section on Concluding Thoughts concludes with the key policy inferences.

Overview Of Trends

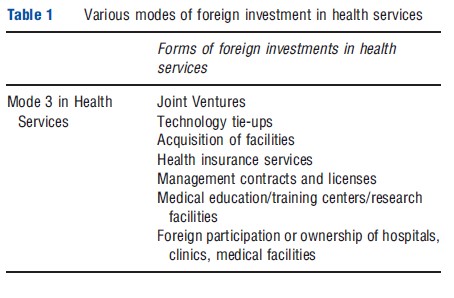

Financing of health services can come from sources within a country such as taxes, insurance funds, and private investment, or from external sources in the form of portfolio and equity investments, commercial loans, FDI, official aid, and nongovernmental financing. As per the GATS, cross border capital flows are also a form of services trade captured under mode 3, which refers to the establishment of any type of business or professional enterprise in the overseas market in order to supply a service (Table 1).

The following discussion provides an overview of recent trends in international capital flows in health services, drawing upon a variety of multilateral and company-level data sources. A few points are worth highlighting. The first relates to the severe data limitations that constrain any efforts to analyze international capital flows in health services. Mode 3 data are not readily available from the Balance of Payments statistics and comprehensive data on measures of health resource flows are lacking. The Foreign Affiliates Trade in Services statistics provide this information, but are available for only a small group of countries. Moreover, such data are not disaggregated by activities and segments within the health services sector and there are potential overlaps with health-related ancillary services and even products. Hence, a comprehensive understanding of the magnitude and breakdown of investment flows in health services is difficult. The second issue concerns the scope of the analysis. This article takes a broad definition of commercial presence and considers any form or level of commercial involvement through greenfield investments, mergers and acquisitions, offices or subsidiaries, or any form of juridical presence as constituting mode 3. The underlying assumption is that there are associated capital flows and authorizations from the host country. Hence, the scope of the analysis is not directly aligned with the GATS definition of mode 3, and terms such as foreign investment, mode 3, and international capital flows are used interchangeably.

The Broad Picture Of Capital Flows In Health Services

Although it is difficult to build a comprehensive picture of foreign investment in health services, the available data indicate that health services play only a marginal role in international capital flows in services. Inward and outward FDI flows and stocks in health services accounted for a meager 0.17% and 0.02% in total services FDI for developed economies, and for only 0.06% of the total inward stock of services FDI in developing countries, in 2005. However, the significance of health services in total services FDI has grown over time. Between 1990 and 2005, inward and outward FDI stocks grew by 762% and 380%, respectively, in developed countries. Data sources for this section include the International Trade Centre (ITC) investment map, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Developments (UNCTAD’s) FDI statistics and Trans-nationality Index online databases, and the Fortune Global 500 index. (UNCTAD World Investment Reports).

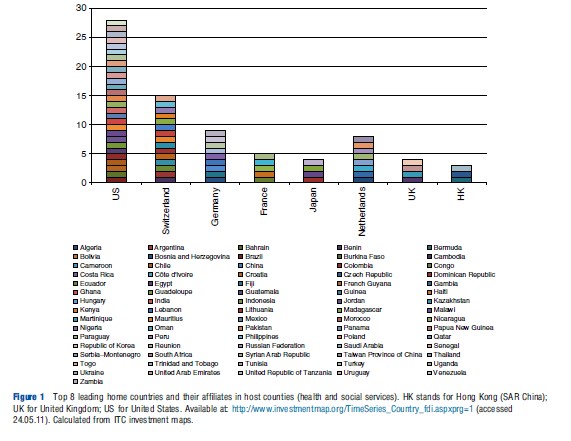

Foreign Affiliates Trade in Services Statistics, which cover a variety of indicators (exports, imports, sales, turnover, and employment) regarding the activities of foreign companies in overseas markets indicate that developed countries have been the leading sources and destinations for FDI in health services. In 2000, the US was the main source as well as destination market in terms of the number of transactions and was the main recipient in terms of the value of transactions. Countries with public sector dominated health systems such as the UK and those with commercially oriented health systems such as the US have featured among the leading exporters and importers of FDI in health services (Waeger, 2007, Table 4, p. 14).

Recent data from the ITC’s investment map confirm that developed countries remain the leading sources for investment in health and social activities, as measured by the number of overseas affiliates. The US is the leading investor, followed by Switzerland (Holden, 2002). However, the range of host countries for health services investment has grown considerably over the past decade. Of the 76 countries, which are host to health investments through affiliates, a large number are developing or least developed nations. Figure 1 shows the leading investor countries along with their corresponding developing country hosts for investment in health services.

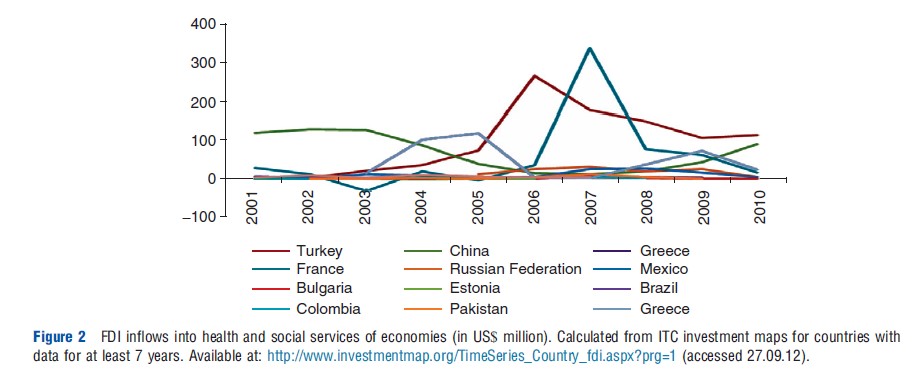

ITC investment maps also provide information on FDI inflows, though this data is available for only a few countries over the 2000–10 period. The US is the leading recipient, with over US$300 million of FDI inflows (in 2010), in health and social services, significantly more than other countries. Figure 2 illustrates the FDI inflows in health services (including net sales of shares and loans to the parent company plus the parent firm’s share of the affiliate’s reinvested earnings plus total net intracompany loans – short and long-term provided by the parent company) for some of the main recipient countries (excluding the US). The data show a sudden significant jump in inward FDI for some countries during this period, though it remains largely stagnant and low for many countries. It must be noted, however, that these FDI statistics pertain to health and social services. Hence, it is difficult to ascertain how much pertains to segments such as hospitals, diagnostics, and clinics directly related to healthcare provision and how much relates to health-related social services or sectors such as health insurance.

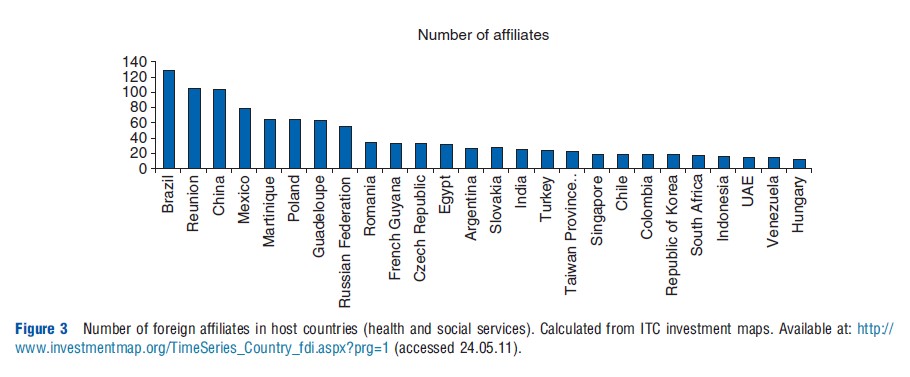

Figure 3 shows the number of foreign affiliates in the health and social services sector of the leading developing country hosts for health services FDI. The countrywise distribution indicates that the extent of foreign participation in the health services sector varies considerably across different developing countries, with Brazil, Reunion (Re´ union is a French island in the Indian Ocean.), China, and Mexico hosting the largest number of such affiliates in 2009.

Transnational Activity In Health Services

Data on mergers and acquisitions in the health and social services sector show a similar upward trend in foreign commercial presence. The number of mergers and acquisitions in health and related social services reached US$14 billion in 2006 in terms of sales transactions, with an annual average value of M&A activity of US$3.9 billion during the 2004–06 period. The largest health services companies were based in and also operated in the developed countries such as the US, UK, and Canada (Cattaneo, 2009).

The growing internationalization of health services firms is also indicated by the Fortune Global 500 internationalization rankings of firms. Based on the Fortune Global 500 list for 2002, Holden (2005) had found that direct health services providers were the least internationalized whereas firms in areas like insurance and pharmaceuticals were the most prominent in internationalization rankings (Holden, 2005). Ten health service companies were listed on the Global 500 List in 205 and nine were ranked in 2006, 2007. The average ranking was 298, 262 and 245, respectively, for each of these years.

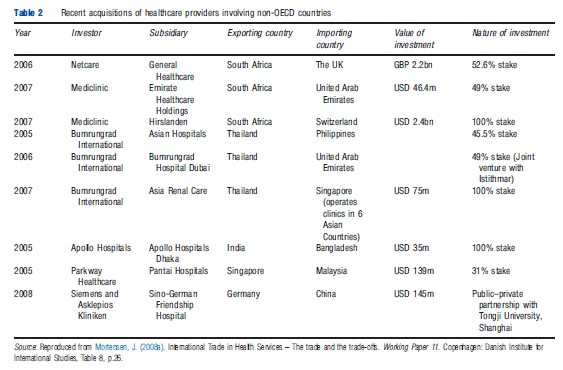

Although the top ranked health services firms are mostly based in and also operate in developed countries (chiefly the US), M&A activity in the hospitals and clinical services segment reflects diversification of source and recipient markets. Table 2 provides information on recent acquisitions of healthcare providers involving developing countries. It reflects the emergence of a small set of transnational hospitals and healthcare providers with both regional and global presence and the entry of several developing country health services firms based in Asia and Africa into foreign markets through M&As. It is also interesting to note the emergence of South–North and South–South flows of capital. The bilateral pattern of M&As indicates the significance of factors such as geographic and cultural proximity, regional markets, growth dynamics, and market size.

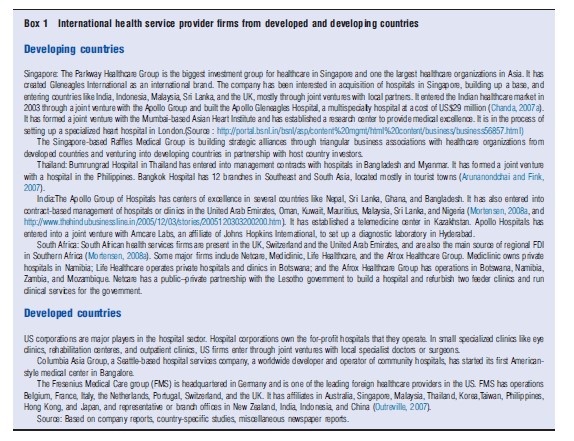

Box 1 highlights the growing regional and global presence of healthcare providers from selected developing and developed countries, and also outlines the formats and strategies adopted by these providers in overseas markets.

Entry into overseas markets is thus occurring through joint ventures, franchises, greenfield investments, acquisitions, tieups, contractual arrangements, and public–private partnerships. Linkages are also evident with other forms of health services trade.

Policies Governing Foreign Investment In Health Services

Increased transnational activity in direct health services reflects FDI liberalization in health services and the incentives given to private players in many developing countries. Since the 1990s, developing countries such as India, Indonesia, Thailand, Sri Lanka, Brazil, and South Africa have opened up their health service sectors to participation by foreign hospitals, diagnostic centers, and clinics. Privatization and deregulation of the healthcare sector in these countries have also contributed to the emergence of private healthcare providers who are globally or regionally competitive. Cambodia, for instance, permits cross border investment in hospital services and foreign ownership. It also permits management of private hospitals and clinics with the condition that at least one director is a national. Foreign firms are allowed to provide dental services through joint ventures with Cambodian legal entities. Similarly, Indonesia is open to foreign healthcare providers, allowing Singaporean, Australian, and Canadian firms to operate in its market. India has permitted automatic approval for 100% FDI in hospitals since 2000. Between 2000 and 2006, there were close to 100 approved FDI projects in hospitals and diagnostic centers for a total of US$53 million from both developed and developing country sources (Chanda, 2007a). Thailand’s open FDI regime for hospital services has resulted in several part foreign-owned hospitals, mainly in the Bangkok area, with investments from Japan, Singapore, China, Europe, and the US.

Box 1 International health service provider firms from developed and developing countries

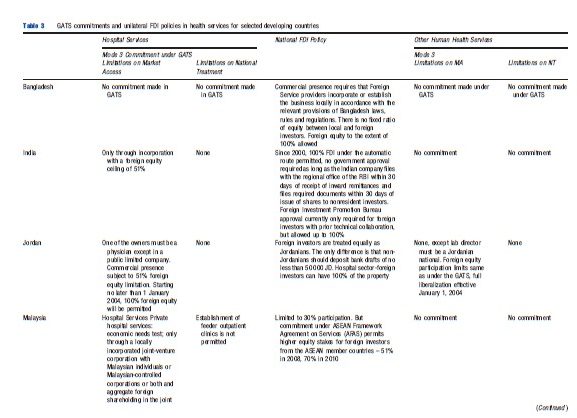

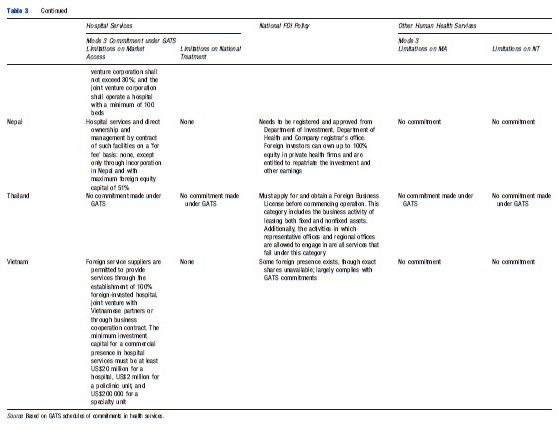

Table 3 summarizes the FDI policies in the health services sector for a representative set of developing countries and their GATS commitments in mode 3. It highlights the extent of liberalization that has been undertaken autonomously in health services and the public policy considerations associated with opening up this sector.

Table 3 indicates that restrictions in the form of limits on foreign equity participation, type of foreign commercial presence, economic needs tests, authorization, certification, and licensing requirements, discriminatory taxes, technology collaboration, and transfer conditions apply in many countries. A comparison of the national policies with the GATS commitments reveals a general unwillingness to legally bind existing FDI regimes or to even undertake GATS commitments in health services.

Countries have also made commitments in health services under bilateral and regional agreements. Obligations of fair and equitable treatment, and pre- and postestablishment national treatment undertaken in Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs), may also have a bearing on foreign investment in health services, to the extent that health services are covered under the BITs. Overall, however, countries tend to leave health services uncommitted and outside the purview of investment obligations under such agreements. Evidence also suggests that liberalization of FDI in health services has not necessarily translated into increased FDI inflows as structural and regulatory factors continue to constrain foreign providers. (High establishment costs, shortage of quality manpower, and low insurance penetration can constrain foreign investors.)

Impact Of Foreign Investment In Health Services

Several studies have discussed the welfare implications of trade in health services, including foreign commercial presence in health services. The effects discussed relate to the resource allocation and accumulation effects of trade liberalization in health services and the likely equity-efficiency tradeoffs. With regard to foreign investment in health services, most authors conclude that the impact on national health systems is shaped by (1) the existing structure of the health system and the extent of commercialization and private sector participation rather than the extent to which the investment is foreign or domestic, and (2) the national regulatory environment. Hence, the consensus is that the costs and benefits may not be related to foreign investment per se but to the existing regulatory environment and the public–private mix characterizing the country’s health system (Chanda, 2001; Smith, 2004; Janjararoen and Supakankunti, 2002).

Overall Cost-Benefit Dynamics

There are three dimensions along which the implications of foreign commercial presence in health services have been assessed. These relate to efficiency, equity, and quality.

Efficiency

Foreign commercial presence can help augment a country’s health resources by bringing in additional financial resources, thereby enabling investment in capacity expansion and economies of scale, potentially alleviating the pressure on government budgets, and allowing public funds to be reallocated more efficiently. At the same time, foreign investment could create inefficiencies by encouraging overinvestment of resources in high-end and highly capital-intensive and specialized treatments and procedures with lower cost-effectiveness, while diverting funding from basic healthcare services. Inefficiencies may also arise, if domestic institutions compete by investing in such technologies and procedures at the expense of broader healthcare needs, and if the country’s import burden increases. There could also be long-term outflows of payments to foreign investors. There may also be direct and indirect subsidization costs for incentives given to foreign investors. However, the efficiency gains or losses are likely to vary across different countries, depending on the regulatory environment governing such inflows and the infrastructural and human resource conditions, which would shape a country’s ability to absorb foreign investment, and the extent to which the private healthcare segment is competitive and dynamic and in a position to derive benefits from the entry of foreign healthcare providers.

Quality

Foreign commercial presence in hospitals and health management may improve the quality of national health systems through the introduction of better management techniques and information systems, better technology, equipment, and infrastructure, and more opportunities for training and skill improvement of medical and management personnel. Foreign-owned or managed healthcare establishments are more likely to follow international standards and to get international certification. There could be positive spillover effects on domestic establishments, which may be incentivized to upgrade their standards, undertake technology investments, and get accredited. Investments in higher end technology and equipment could also provide greater exposure to healthcare professionals, thus helping improve their skills. Better quality small and midsize hospitals, diagnostic labs, and clinics are also likely to tie up with larger hospitals in terms of referral services, thus potentially improving outreach and quality of healthcare for all. Such improvements in the quality of the domestic healthcare system and presence of foreign healthcare providers of global standards could in turn benefit the country by reducing spending on expensive treatments overseas. Once again, these gains would be shaped by the regulatory environment for ensuring quality and standards, the ease with which technology and equipment can be accessed, and the dynamism of the domestic healthcare system.

Equity

Foreign commercial presence may have positive as well as negative implications for equity. Such establishments are more likely to cater to the urban and affluent segments of the population who can afford to pay, potentially aggravating existing inequities in access to healthcare between the rich and poor, between the urban and rural populations. Such establishments are more likely to focus on tertiary care, specialized treatments, and curative and intervention-oriented procedures rather than primary and preventive healthcare needs. There may be cost implications as foreign-owned and managed health providers are likely to be costlier given their higher capital intensity and focus on quality systems and processes and accreditation, which could adversely affect access by the poor out-of-pocket paying population. Foreign investment in health services, particularly in hospitals could also distort the healthcare market by encouraging brain drain of the most qualified and specialized health personnel toward such establishments and away from domestic establishments with offers of better pay and facilities. The latter could adversely affect the quality of medical manpower in competing institutions, particularly, public sector hospitals. Thus foreign commercial presence could accentuate the dualistic structure that often characterizes health systems. Such two-tiering could also weaken the constituency for improving public services.

But there are potential positive implications. The entry of foreign healthcare providers is likely to augment employment opportunities in the healthcare sector at all levels, with better remuneration, especially for specialized and senior medical professionals. Such establishments are also more likely to attract overseas medical professionals and returnees, who are internationally accredited, and could augment human resource capacity and quality in the host country. Some studies have highlighted that foreign healthcare providers may have greater scope to undertake cross-subsidization of poor patients, to do more outreach and extension services, and to establish themselves in second tier cities and towns, given their larger volumes and deeper pockets. Again, the equity implications, positive and negative, are likely to be contingent on factors such as the extent of health insurance penetration, how segmented is the prevailing healthcare system, whether there are regulatory requirements to cross-subsidize the poor and ensure access to the poor in foreign investor hospitals, and the overall quality and availability of human resources.

There are also externalities from foreign commercial presence in health services to other modes of health services trade. Foreign investment in health services can complement medical value travel, telemedicine, and movement of health personnel. Foreign commercial presence and setting up of internationally accredited and recognized hospitals could help attract foreign patients and augment medical value travel exports, reduce imports of health services through outflows of domestic patients, and encourage telemedicine exports. Outward investment in health services through acquisitions, new ventures, and management and other tie-ups can also benefit exporting institutions through increased foreign exchange earnings, inflows of foreign patients, and greater exposure for their professionals.

Evidence From Selected Countries And Firms

The information in this section is based on company reports (Arunanondchai and Fink, 2007; Chanda, 2007a,b, 2010; Timmermans, 2002; Benavides, 2002; Janjararoen and Supakankunti, 2002; Wadiatmoko and Gani, 2002; Mortensen, 2008a,b), and miscellaneous newspaper articles.

Secondary evidence from a sample of transnational health services firms confirms the aforementioned implications of foreign investment in health services.

- South African hospital companies have succeeded in winning healthcare contracts abroad, including the UK’s National Health Service. Netcare established its presence in the UK in 2001. It has helped in reducing wait lists in selected areas of the UK. In 2006, Netcare led a consortium that acquired General Healthcare Group owner of the largest independent hospital operator BMI Healthcare, making it one of the largest healthcare groups with 119 hospitals and almost 11 000 beds. Under this contract, Netcare sends teams of medical personnel from South Africa to its establishments in the UK for fixed periods, thereby enabling its employees to work 4–6 weeks at a time abroad, to get exposure to opportunities overseas, and to supplement their income with fixed term contracts abroad. Such ventures have also helped to reduce staff turnover and improve retention of skilled personnel in South Africa (see, http://www.netcareuk.com).

- Cuba has used joint ventures with Canadian, German, and Spanish companies to attract patients from these countries for specialized treatments. Such investments have helped it to become a hub for teleconsultation and telediagnostic services for the Central American and Caribbean market and have facilitated the establishment of specialized Cuban clinics in Central and Latin America where Cuban physicians and nurses are employed.

- In its bid to become the medical center of the Arab world, Jordan has provided incentives for national and foreign private investment in the health sector. This has led to the establishment of several private hospitals with foreign financing and tie-ups, benefiting the Jordanian health system through state-of-art technology, computerized links with prestigious health centers in Europe and North America, and medical value travel exports to the region.

- India’s Apollo Group of Hospitals highlights the linkages between mode 3 and other forms of trade in health services. Apollo’s mode 2 exports have been facilitated by its overseas marketing offices and management contracts with hospitals in the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Oman, Kuwait, Mauritius, Tanzania, UK, Sri Lanka, Bhutan, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. Apollo Gleneagles, which is a joint venture with the Singapore-based Parkway Group, exports health services to patients from neighboring countries like Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan, and Myanmar. It also provides telemedicine services such as medical consultation, diagnostic, telepathology, teleradiology, and scanning services. Apollo also provides contract research and medical education and training services through its overseas subsidiaries, using a combination of cross border supply (online training and research services) and temporary onsite deployment of professionals at its subsidiaries, thereby benefiting its own professionals and also host country professionals.

- In India, Hindustan Latex Ltd and Acumen Fund (USA) have created a joint venture to develop a small chain of high-quality and affordable (30–50% of regular price) maternity hospitals to serve the low-income population in underserved Indian regions. The aim is to make this a global model for increasing access to qualitative and affordable healthcare for the poor.

- The public and the private sectors in China have jointly developed a strategy to attract foreign health providers to set up commercial presence. Chinese institutions have entered into joint ventures with partners in the medical profession and with local authorities overseas. Traditional Chinese Medicine facilities have been established in more than twenty countries. Such joint ventures help spread Traditional Chinese Medicine overseas, enable the deployment of Chinese health workers and their exposure to other systems under contractual arrangements, and help attract patients to China.

- Evidence from some ASEAN countries shows that foreign investor hospitals can aggravate the existing inequities in the host country’s healthcare system. Most of these hospitals have located in and around the main cities such as Bangkok and Jakarta and target the upper income segment. The Indonesian government has thus imposed fewer regulatory requirements on foreign investors in regions with weak public health infrastructure to attract foreign investors to islands other than Java and to the smaller cities. The Indonesian government has also imposed a requirement to accommodate at least 200 beds in foreign investment hospitals.

Primary Evidence On Impact: Case Study Of India

A survey of 25 hospitals conducted in 2007 across several major cities in India examined the realized or perceived impact of foreign investment in Indian hospitals on quality, affordability, infrastructure, range of services, technology, accessibility, and prices. The survey findings largely corroborate earlier studies (Chanda, 2007a,b).

Services And Infrastructure

Foreign investor hospitals were found to focus on more advanced and specialty services compared to domestic hospitals, indicating a greater emphasis on niche areas and on high revenue generating curative and surgical interventions as opposed to preventive care. The survey also revealed that foreign investor hospitals tend to invest more heavily in high-end technology and state-of-the-art equipment, which in turn leads to a difference in approach to medical care, with more intensive use of medical equipment in order to recover investments. On average, foreign investor hospitals were also found to have more medical facilities, more equipment, and to be larger in terms of the number of beds, rooms, ambulances, and Intensive Care Unit infrastructure. Foreign funded institutions also reported greater availability of postoperative care facilities and critical care services. There was also greater availability of medical staff for critical care and specialized services as opposed to general care.

Human Resources: Remuneration And Quality Issues

The survey findings showed that foreign investor hospitals pay higher salaries to their medical staff at all levels and particularly to senior specialists, suggesting the possibility of internal brain drain from domestic private as well as public sector hospitals to foreign investor hospitals. The findings on remuneration also suggest that there could be positive implications for employment and income opportunities for medical personnel. Hence, there is evidence on a likely two-tiering impact.

Costs Of Services

The data on costs of different procedures and treatments indicated that foreign investor hospitals tended to be more expensive than comparable domestic health providers. Indepth discussions with industry experts revealed that hospitals were on average 15–30% costlier than small and medium size healthcare providers.

Spillover Effects

The study found a strong spillover effect on medical value travel. Increased foreign investor presence in hospitals was seen as facilitating medical value travel to India by enabling tie-ups with foreign health insurance providers and development of customized insurance products for elective surgeries by overseas patients in India with follow-ups abroad. Foreign investment in hospitals was seen as encouraging the entry of multinational insurance companies, which would be more comfortable in dealing with foreign funded corporate hospitals that were accredited and accountable. Respondents also noted that foreign investment in hospitals would spur expansion of activities in other areas such as medical transcriptions, back-office medical outsourcing, and telemedicine as well as promotion of opportunities in other areas such as clinical trials outsourcing, research and development, and medical training and education. Several respondents noted the likely boost to telemedicine from foreign commercial presence, given investments by foreign players in IT systems. Strong positive externalities were also perceived in the form of technology and knowledge transfer through tie-ups for research and development, technology sharing, professional exchange, and continuing medical education.

Concerns

The survey highlighted some areas of concern, along the lines suggested by other studies. Increased foreign investment in hospitals was seen as aggravating the internal brain drain of medical personnel from public to private healthcare establishments and making it more difficult for the public sector to retain doctors and teachers in affiliated medical colleges. It was noted that the increased focus on earning money would mean less focus on teaching and research, especially on issues relevant to local conditions. Several respondents highlighted the fact that small and medium size nursing homes would face greater competition from the large corporate hospitals, have difficulty retaining staff, and would become less attractive as they would not be able to provide many services under one roof. Hence, many would have to close down or would be acquired by the larger players. Similar concerns were expressed for independent pharmacies and diagnostics/labs. It was also felt that as foreign funded hospitals provide better remuneration, their expansion would put upward pressure on wages and salaries of medical personnel and thus increase competition for quality manpower. A third concern was related to costs, affordability, and relevance of healthcare following increased foreign investment in hospitals and possible adverse effects on the poor who might be squeezed out of the system. Several respondents expressed concern that foreign investment in hospitals and the focus on profits and returns for shareholders would lead to increased healthcare costs, increasing the existing income and geographic divide in healthcare delivery.

Concluding Thoughts

Foreign investment in health services has grown over the past decade, taking a variety of forms and involving a growing number of developed and developing countries. Although it is difficult to quantify the impact of foreign investment on national health systems, several general studies highlight the likely pros and cons of such investment. There is broad agreement on the various positive and negative implications. An important conclusion of these studies is that the impact on national health systems is a function of regulatory frameworks, the prevailing market structure, and the extent of commercialization. Although foreign investment may have adverse implications for equity, affordability, and on the public sector, the real underlying cause could be the prevailing distortions in the healthcare system and not foreign investment.

A key policy inference is that it is possible to shape the impact of foreign investment on national health systems and that possible negative fallouts should not lead to a restrictive approach to such investments. The negative effects can be mitigated and prevented. The positive effects can be facilitated through appropriate policies and regulations. For instance, public–private partnerships and facilitation of linkages between the public and private health services segments with regard to medical education, training, staff and information exchange, can be encouraged to reduce the scope for two-tiering. Initiatives to increase insurance penetration and conditions requiring foreign investors to provide medical outreach and extension services in less served areas, could mitigate the negative equity fallouts.

Clearly, more research is required across a mix of countries with different health systems and regulatory environments to draw more definitive, evidence-based conclusions. More dialog is also required between the commerce and health ministries and investment boards to enable an integrated social and economic perspective and to accordingly frame an appropriate mix of investment incentives and conditions to balance the tradeoffs.

References:

- Arunanondchai, J. and Fink, C. (2007). Trade in health services in the ASEAN region. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 147. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Benavides, D. (2002). Trade policies and export of health services: A development perspective. In Drager, N. and Vieira, C. (eds.) Trade in health services: Global, regional and country perspectives, pp. 53–69. Washington, DC: PAHO/WHO.

- Cattaneo, O. (2009). Trade in health1 services: What’s in it for developing countries. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 5115. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Chanda, R. (2001). Trade in health services. Paper No. WG4:5. WHO, Geneva: Commission on Macroeconomics and Health.

- Chanda, R. (2007a). Foreign investment in hospitals in India: Status and implications. New Delhi: WHO Country Office, India and the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare.

- Chanda, R. (2007b). Impact of foreign investment in hospitals: Case study of India.Harvard Health Policy Review 8(2), 121–140.

- Chanda, R. (2010). Constraints to FDI in hospital services in India. Journal of International Commerce, Economics and Policy 1(1), 121–143.

- Holden, C. (2002). The Internationalization of long term care provision. Global Social Policy 2(1), 47–67.

- Holden, C. (2005). The internationalization of corporate healthcare: Extent and emerging trends. Competition & Change 9(2), 185–203.

- Janjararoen, W. and Supakankunti, S. (2002). International trade in health services in the millennium: The case of Thailand. In Drager, N. and Vieira, C. (eds.) Trade in health services: Global, regional and country perspectives, pp. 87–106. Washington, DC: PAHO/WHO.

- Mortensen, J. (2008a). International Trade in Health Services – the trade and the trade-offs. Working Paper 11. Copenhagen: Danish Institute for International Studies.

- Mortensen, J. (2008b). Emerging multinationals: The South African hospital industry overseas. Working Paper 12. Copenhagen: Danish Institute for International Studies, University of Copenhagen.

- Outreville, J. (2007). Foreign direct investment in the health care sector and most-favoured locations in developing countries. European Journal of Health Economics 8, 305–312.

- Smith, R. (2004). Foreign direct investment and trade in health services: A review of the literature. Social Science and Medicine 59, 2313–2323.

- Timmermans, K. (2002). Overview of the South-East Asia region. In Drager, N. and Vieira, C. (eds.) Trade in health services: Global, regional and country perspectives, pp. 83–86. Washington, DC: PAHO/WHO.

- Wadiatmoko, D. and Gani, A. (2002). International relations within Indonesia’s hospital sector. In Drager, N. and Vieira, C. (eds.) Trade in health services: Global, regional and country perspectives, pp. 107–117. Washington, DC: Pan-American Health Organization/WHO.

- Waeger, P. (2007). Trade in health services: An analytical framework. Working Paper No. 441. Kiel, Germany: Kiel Institute for world Economics, Advanced Studies Programme 2005/2006.

- Blouin, C., Drager, N. and Smith, R. (eds.) (2006). International trade in health services and the GATS, current issues and debates. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Chanda, R. (2002). Trade in health services. Bulletin of the World Health Organisation 80, 158–163.

- Fortune Global 500 list. Available at: https://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/global500/2010/index.html.

- Gupta, I. and Goldar, B. (2001). Commercial presence in the hospital sector under GATS: A case study of India. New Delhi: WHO SEARO.

- Investment map. Geneva: ITC. Available at: https://www.investmentmap.org/home.

- Mackintosh, M. (2003). Health care commercialisation and the embedding of inequality. RUIG/UNRISD Health Project Synthesis Paper. Geneva.

- Maskay, N. M., R. K. Panta, and B. P. Sharma (2006). Foreign investment liberalization and incentives in selected Asia-Pacific developing countries: Implications for the health service sector in Nepal. Working Paper Series No. 22. Bangkok: Asia-Pacific Research and Training Network on Trade, ARTNeT.

- Smith, R., Chanda, R. and Tangcharoensathien, V. (2009). Trade in health-related services, Trade and Health Series. The Lancet 29–37.

- UNCTAD, FDI Statistics. online database. http://unctadstat.unctad.org/EN/Index.html

- Woodward, D. (2005). The GATS and trade in health services: Implications for health care in developing countries. Review of International Poliltical Economy 12(3), 511–534.