Poor performance of health care providers plagues the delivery of health services in many low- and middle-income countries. The underlying reasons are complex and incompletely understood, but poor performance is not simply due to inadequate training or deficiencies in provider knowledge.

Instead, a growing body of evidence documents substantial deficits in provider effort. One striking example is the high absenteeism rates (as high as 75%) among health professionals documented in a number of studies. When providers are present, a sizeable ‘know-do’ gap (or failure to do in practice what a provider knows to do in principle) also contributes to low-quality medical care. Provider effort may also not focus directly on improving health – for example, health professionals may provide unnecessary services that are not medically appropriate (e.g., intravenous glucose drips to create the illusion of therapeutic effectiveness). Moreover, even when providers exert appropriate effort during a clinical encounter, they may do little to promote the health of their patients outside of the encounter (e.g., through prevention and outreach activities).

One might expect that given weaker market incentives, these problems would be more prevalent in public sector health service delivery. However, suboptimal provider effort can be sustained in equilibrium in all sectors, including private practice, due to well-known market failures. For example, a well-established literature demonstrates that asymmetric information limits the ability of patients and the lay public to observe provider effort or judge medical care quality. As a result, patients are unable to penalize underperforming providers through their choices. These problems are compounded by market conditions and rigidities common in low and middle-income countries, including inadequate regulatory processes and a relatively large government role in financing and delivering health services (e.g., given the more prevalent infectious diseases and larger positive externalities in service delivery).

To better align provider incentives with patient and population welfare (or health – one argument of welfare), ‘pay-for-performance’ schemes have become increasingly common in developing country health service delivery. In principle, the idea is straightforward: drawing on the logic of performance pay in human resource management, this approach rewards providers directly for achieving prespecified performance targets related to health. Use of performance incentives in wealthy countries began in earnest during the 1990s with programs that rewarded both process indicators and measures of clinical quality. Examples of performance targets include immunization rates; disease screening; adherence to clinical guidelines; and the adoption of case management processes, physician reminder systems, and disease registry systems. The UK went further with the National Health Service’s Quality and Outcomes Framework, tying physician practice bonuses to a comprehensive range of quality indicators. Performance pay in low and middle-income country health programs emerged in the late 1990s, and its use has grown rapidly since then.

In practice, pay-for-performance contracts are complex and fraught both with difficult tradeoffs and with the possibility of ‘multitasking’ and other unintended consequences. This article outlines the key conceptual issues in the design of pay-for-performance contracts and summarizes the existing empirical evidence related to each. In doing so, it focuses on four key conceptual issues: (1) what to reward, (2) who to reward, (3) how to reward, and (4) what perverse incentives might performance rewards create. The article concludes by highlighting important areas for future research and by noting the overall lack of evidence on many key aspects of incentive design in the health sector.

What To Reward

If ‘you get what you pay for,’ then it presumably follows that one should pay for what one ultimately wants. If a health program’s primary objective is good patient or population health outcomes, it would seem natural for performance incentives to reward good health or health improvement directly rather than the use of health services or other health inputs. Rewarding health outcomes rather than health input use not only creates strong incentives for providers to exert effort, but it can also create incentives for providers to innovate in developing new, context-appropriate delivery strategies. Put differently, rather than tying rewards to prescriptive algorithms for service provision (often developed by those unfamiliar with local conditions), rewarding good health outcomes encourages providers to use their local knowledge creatively in designing new delivery approaches to maximize contracted health outcomes.

In practice, however, very few pay-for-performance schemes have rewarded good health. At the time of writing this review, the authors are aware of only two: performance incentives for primary school principals in rural China to reduce student anemia and incentives for Indian day care workers in urban slums to improve anthropometric indicators of malnutrition among enrolled children. In the Chinese study, researchers measured student hemoglobin concentrations at the beginning of an academic year, issued incentive contracts rewarding anemia reduction to principals shortly afterwards, and measured student hemoglobin concentrations again at the end of the school year. School principals responded creatively, persuading parents to change their children’s diets at home as well as providing micronutrient supplementation at school; and anemia prevalence fell by approximately 25%. In the Indian study, researchers measured child anthropometrics at day care facilities, issued incentive contracts rewarding providers for each child with an improved malnutrition score, and repeated anthropometric measurement 3 months later. In response, day care workers visited mothers’ homes and promoted the use of nutritious recipe booklets; malnutrition indicators declined by approximately 6%.

The fact that so few pay-for-performance programs reward health outcomes may reflect important limitations to doing so that arise in practice. Instead, performance incentives generally reward the use of prespecified health inputs. In the following sections, shortcomings and tradeoffs inherent in incentive contracts that reward health outcomes will be discussed.

Share Of Variation In Contracted Outcome Under Provider Control

One drawback to rewarding good health is that even when exerting optimal effort, a relatively small amount of variation in health outcomes may be under the control of providers. For illustration, consider the case of neonatal survival. Maternal health behaviors during pregnancy are key determinants of birth weight, and low birth weight is a leading risk factor for neonatal death. Although rewarding maternity care providers for neonatal survival could in theory motivate them to engage expectant mothers from an early stage of their pregnancy, providers may be unlikely to succeed or may believe a priori that they will be unable to change maternal health behaviors. Patients or community members may also respond to changes in provider behavior caused by performance incentives; in some cases, these responses may undermine provider actions. For example, if educators or health providers take direct action to improve nutrition because of performance incentives, parents may respond by reducing children’s dietary quality at home. In both cases, if providers do not believe that their effort will ultimately be rewarded, they may simply not respond to the performance incentive.

A clear (and common) alternative is to reward the use of health services and inputs, particularly those that are relatively sensitive to provider effort. Providers generally have a greater influence on service use than health outcomes, and even more so on quality of clinical care. In several rigorous studies of pay-for-performance incentives in Rwanda, providers were rewarded for prenatal care visits, immunizations among children and pregnant women, institutional deliveries, HIV testing, and a wide range of service quality indicators. Incentive payments were offered for each service provided and were weighted using overall quality scores. This set of incentives motivated providers both to increase delivery of contracted services and to raise the overall quality of care. Researchers observed that the program increased institutional delivery rates by 23% and preventive service use among children under the age of 4 years by 25–50%, and it also reduced the ‘know- do’ gap by 20%. Although not directly contracted, infant weight-for-age and child (2–4 year old) height-for-age rose by approximately 0.5 and .25 standard deviations, respectively. Researchers also observed that the incentives led to a 15% increase in the rate of HIV testing and counseling among couples, and an 18% increase in the probability that both partners in HIV-discordant households had been tested for HIV at least once.

Interactions With Provider Skill/Human Capital Base

A second limitation to rewarding good health outcomes is that providers may not possess adequate ability to innovate if they lack the necessary skills and human capital. These skills can be both technical and interpersonal. Scholars suggest that providers may be unsuccessful in responding to performance incentives when success requires changing the patient behavior (which requires skills beyond clinical ability). In the Rwandan program, providers were unsuccessful in increasing contraceptive use and in persuading patients to complete the contracted sequence of four prenatal care visits in part because of local patient preference (superstitions about acknowledging pregnancies at an early stage). To address this shortcoming, one program in the Democratic Republic of Congo paired performance incentives with consulting services for community outreach and business planning. Health facility managers were encouraged to submit quarterly business plans detailing their strategies to achieve incentivized targets, and consultants provided them with custom-tailored advice.

Measurement Of Contracted Outcomes

A third obstacle to rewarding good health is that health outcomes can be more difficult and expensive to measure than health service or input use, particularly when physiological health indicators must be measured directly. For example, all else equal, the expense of measuring hemoglobin concentrations would potentially be an important barrier to scaling up the China performance pay program described above. Alternatively, incentives tied to service and input use have successfully relied on combinations of self-reporting and random audits to measure contracted outcomes on a larger scale. Examples of contracted health inputs measured this way include well baby visits and adherence to clinical protocols during medical visits. Finally, measurement of contracted outcomes (either health input use or health outcomes) among patients in clinical settings may pose fewer measurement challenges than in community wide settings section (Perverse incentives and unintended consequences considers tradeoffs between rewards for outcomes among patients vs. population members).

Who To Reward

Another important issue in designing performance incentives is deciding who to reward. Which agents at what organizational level will be most efficient and effective in improving on contracted outcomes? This section describes conceptual issues in contracting at the macro (or organizational) and the micro(individual) level.

Macrolevel Incentives: Organizations And Local Government

At the macrolevel, international organizations (like the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization and the Millennium Challenge Corporation) increasingly use ‘results-based financing’ in providing aid. Central governments in low and middle-income countries also frequently contract with private organizations or transfer resources to local government to deliver health services – and performance incentives are often included in these schemes. As performance pay shifts risk to incentivized agents, the more risk averse the agent, the greater the expected compensation must be (all else equal). One advantage of organizational-level incentives is that collectively, organizational agents may effectively be less risk averse than individual employees. This is because idiosyncratic risk that effort will not result in good performance – and thus not be rewarded – is pooled across individuals within organizations. As a result, overall program costs may be lower when contracting at the organizational level (all else equal). However, contracted organizations must then solve their own internal principal–agent problems, and they may pass the costs of doing so on to the principals contracting with them.

There are many circumstances under which central governments ‘contract-out’ health service delivery to private organizations (typically non-governmental organizations (NGOs)). One is settings in which public sector facilities are largely absent – for example, regions of postconflict Afghanistan and Haiti. Under these conditions, governments and international organizations have contracted with NGOs to open facilities, recruit and train providers, and manage all aspects of service delivery. In the context of Afghanistan and Haiti, achieving performance targets was rewarded with operating budget transfers of up to 10% of the base contract amounts (paid by the World Bank and the US Agency for International Development (USAID), respectively). In Afghanistan, studies found that these contracting strategies were associated with improvements in service availability (measured as the ratio of facilities to population, which increased by approximately 30%, and the share of facilities providing antenatal care, which rose by 45–75%) and institutional delivery rates (which roughly doubled). In Haiti, research suggested that performance pay was associated with 13–24% point increases in full childhood immunization coverage and 17–27% point increases in institutional delivery rates.

Contracting-out also occurs when public sector facilities exist but perform poorly. For example, in 1999, the Cambodian Government began contracting with NGOs to manage health service delivery in five randomly selected districts (eight districts were chosen for contracting, but not all districts had suitable quality proposals from NGOs). Contracts rewarded eight explicit performance indicators (immunization rates, vitamin A supplementation, antenatal care use, medical supervision of deliveries, institutional delivery rates, contraceptive use, and use of public vs. private sector health facilities). Researchers found that after 5 years, performance-based contracting led to a 32% point increase in antenatal care use, a 16% point increase in completion of recommended childhood immunizations, and a 17% point increase in vitamin A supplementation. Cambodia’s contracting strategy also improved the general facility operations (24 h service availability, staff attendance, managerial supervision, and equipment availability).

Macrolevel performance incentives have also become increasingly common in the public sector. In the 1980s, central governments in many low and middle-income countries began transferring funds for service provision to local governments, decentralizing authority over policy design and management. One of the rationales for decentralization is that local governments have superior information about local preference and are therefore better able to satisfy them. However, even if local governments have superior information about local preference, they do not necessarily have strong incentives to satisfy them. Decentralization can therefore include performance-based incentives. For example, a recent initiative in Indonesia gave block grants to village leaders to provide maternal and child health services and to run schools. In a randomly selected subset of villages, the size of subsequent block grants was tied to performance according to 12 performance measures (8 maternal and child health indicators and both enrollment and attendance in primary and secondary schools). Scholars found that with performance incentives, midwives in treatment villages worked longer hours, increasing the availability of health services – and prenatal care visits rose by 37% points. Local administrators in incentivized districts also used central government funds more efficiently, negotiating savings in education (without any apparent decline in school attendance) and reallocating the savings to the health sector.

Under all of these circumstances, organizational autonomy may be critical for the success of incentive programs. The Cambodian program experimented explicitly with the degree of independence given to contracting NGOs, using both more restrictive ‘contracting-in’ and more autonomous ‘contractingout’ arrangements. Management and facility indicators improved more in contracting-out districts, and there is suggestion that health indicators did as well. Other cases illustrate the breadth of responses to performance incentives enabled by autonomy. For example, hospitals in Sao Paulo, Brazil with municipal health delivery contracts that rewarded hospital efficiency, patient volume, and service quality developed creative organizational strategies tailored to their own hospital settings. Hospital spending fell and efficiency indicators rose without measurable declines in service quality; researchers estimate that to produce comparable changes in patient discharges absent performance incentives, hospitals would need to increase spending by approximately 60%.

An important limitation of macrolevel incentives is that they may not translate into private rewards for organizational leaders. Although performance incentives could, in principle, be structured this way, to date they have generally been designed as operating budget transfers and eligibility for future contracts (rewards paid as budget transfers vs. private income is discussed in more detail in Section How to Reward). A related drawback is the possibility that organizational policies and regulations limit organizational or local government ability to solve their own internal principle–agent problems (e.g., if managers are not permitted to use budget transfers for employee bonuses). In Cambodia, contracting NGOs increased the use of many (presumably productive) health inputs, but actual health outcomes (the infant mortality rate and diarrhea incidence among children under 5 years) did not improve. NGOs managing hospitals in Afghanistan and Costa Rica (under similar programs) made improvements in facility management and service provision, but there were no measurable gains in health input use (e.g., immunizations).

Microlevel Incentives

At the microlevel, organizations often use performance incentives to solve principal–agent problems with individual employees. These incentives can target upper-level managers and/or rank-and-file providers that they supervise.

An important virtue of rewarding managers for good performance is that they possess greater flexibility for innovation in service delivery. In contrast, lower-level health workers often must follow detailed, highly prescriptive protocols from which they are not allowed to deviate. For example, a recent study shows that Chinese primary school principals (who manage schools) offered performance rewards for reducing student anemia not only supplemented school meals with vitamins, but they also took the initiative to discuss nutrition with parents, persuading them to increase their children,s consumption of iron-rich foods at home. As a result, anemia prevalence among participating children fell by roughly 25%. In Nicaragua, health facility managers were given performance incentives for offering and providing both prenatal care and well child services to a large share (90%) of local CCT program beneficiaries. In response, managers took the initiative to partner with community organizers (promotoras), school teachers, and the local media to conduct community outreach campaigns encouraging mothers to bring their children for checkups. These managerial efforts were reportedly successful: nearly all providers were judged to have achieved the performance targets, preventive care use increased by 16% points, and vaccination rates rose by 30% points.

In practice, many pay-for-performance schemes to date have rewarded individual providers rather than their managers for good performance. Although rank-and-file health workers may have less flexibility to innovate in service delivery, their effort may ultimately matter most for organizational performance. Additionally, because they have the most direct contact with target populations, individual providers may also have better knowledge about local conditions. For example, day care workers in the Indian program rewarding reductions in malnutrition made more frequent home visits in addition to providing more nutritious meals at day care facilities. Through these home visits, they encouraged mothers to use nutritious recipe booklets, and malnutrition among children at their day care centers declined by 4.2% over a 3-month period. In Rwanda, individual public sector providers responded to incentives for higher prenatal care and institutional delivery rates by partnering with midwives to identify and refer pregnant women for services. The associated increase in institutional deliveries was 10–25% points.

In addition to lacking flexibility to innovate in service delivery, there can be other limitations to incentivizing individual health workers as well. A potentially important one is that rewarding health workers for their own individual performance may create disincentives for teamwork or cooperation. Alternatively, rewarding providers for group performance creates incentives for free-riding because individual health workers do not bear the full cost of shirking – and may be rewarded for good performance among coworkers.

How To Reward

Using performance incentives to increase provider effort necessarily requires assumptions about what motivates providers. It is reasonable to assume the providers care about both financial compensation and patient welfare to varying degrees. However, human motives are complex, and other factors undoubtedly play a role too – professional recognition and the esteem of colleagues, pride in one’s work, opportunities for professional advancement (career concerns), working conditions, and amenities where one lives, for example. From the standpoint of policy or program design, many of these other factors cannot be translated into performance rewards as easily as financial incentives. However, these other motives can interact with financial incentives in important ways.

This section discusses general conceptual issues in the structure of performance incentive contracts.

Balancing Fixed Versus Variable Compensation

As discussed in the literature outside of health (on executive compensation, for example), performance pay should optimally balance fixed (unconditional) and variable (performance-based) pay. On one hand, performance bonuses must be sufficiently large to influence provider behavior, and on the other aligning executive effort with firm interests may require that a large share of total compensation be tied to firm performance through performance pay. Several studies suggest that in health care, performance incentives may be ineffective if they are too small.

However, increasing variable pay as a share of total compensation increases the financial risk borne by providers. As providers are generally risk-averse (to varying degrees), they must be compensated for bearing additional risk inherent in pay-for-performance contracts. Negotiations over a health service delivery contract in Haiti between an NGO (Management Sciences for Health) and USAID illustrates this point. When renegotiating its contract, Management Sciences for Health was only willing to accept the additional risk imposed by performance pay if USAID would increase the total amount that could be earned to exceed contractual payments under the alternative unconditional contract (under the performance pay contract, fixed payments were set to 95% of the unconditional contract amount, and an additional 10% was made conditional on good performance).

The Functional Form Of Provider Rewards

A second issue in the structure of performance pay contracts is the functional form mapping incentive payments onto performance indicators. Absent knowing what the contract theory literature suggests is needed for optimal incentive contract design, a simple approach is to offer rewards that are linear in contracted outcomes. Examples include constant incremental rewards per child reduction in malnutrition, per child reduction in anemia, or per infant delivery supervised by a skilled birth attendant.

Other programs have adopted a step-function approach, offering bonuses for surpassing one or more bright-line performance thresholds. Depending on its specific form, this approach can have theoretical grounding and may also be appropriate when thresholds have clinical significance (e.g., vaccination rates at levels that confer herd immunity). Contract theory suggests that optimal incentive contracts are likely to be nonlinear in contracted outcomes, and step functions could provide a reasonable approximation of these nonlinearities. Some scholars also argue that setting bright-line aspirational goals could change institutional culture to be more results or goal oriented. Although there is little evidence among studies of performance pay, bright-line performance incentives may help to focus attention on contracted outcomes when provider attention is scarce as well.

A drawback to the step-function approach can be a greater risk that provider effort will not be rewarded. Specifically, it creates strong incentives in the neighborhood of a threshold, but it may also be a poor motivator for health workers far below (or above) a threshold. The information required for optimal contract design (including the cost of provider effort, the health productivity of provider effort, and the utility functions of both providers and the contracting principal) is also unlikely to be available in practice.

Salary Versus Operating Budget Rewards

Structuring performance rewards as private income or operational budget revenue also requires assumptions about what motivates providers. In one extreme, if providers were purely motivated by private financial considerations, offering rewards as private income would presumably induce them to exert a greater effort. In the other extreme, if providers were purely philanthropic, incentive payments made as operational revenue could be more effective. Given that preference are mixed in reality (and also include other things such as professional esteem, pride in one’s work, career aspirations, etc.), predictions about the relative effectiveness of different types of financial incentives are ambiguous and may be context specific. One study suggests that NGO employees providing health services in Afghanistan responded markedly to performance incentives even though bonuses accrued to facilities and did not result in personal financial gain. In principle, combinations of the two are possible, although one is unaware of schemes that mixed the two. In practice, macrolevel rewards are often paid as operational revenue, whereas microlevel rewards are typically offered as private income.

Nonfinancial Incentives

Although pay-for-performance contracts strengthen extrinsic incentives, intrinsic motivation is commonly thought to be an important determinant of provider effort as well. Although not focused specifically on health care provider behavior, research on intrinsic motivation in psychology suggests that more altruistic individuals work harder to achieve organizational goals. In the health sector, altruistic individuals are more likely to work for health delivery organizations with explicit charity mandates, suggesting that intrinsic motivation may be heterogeneous across types of health facilities. Health care providers with greater intrinsic motivation may also be more responsive to professional recognition among community members or peers. In such cases, nonfinancial rewards as well as other psychological tools (such as priming, task framing, and cognitive dissonance) may be close substitutes (or may even be more effective) than financial incentives.

Qualitative and anecdotal evidence from field studies support the hypothesis that health care providers are intrinsically motivated. Health workers employed by NGOs in postconflict Afghanistan reportedly felt a great sense of pride and accomplishment after meeting contracted performance targets. A program (not formally evaluated) in Myanmar offered new scales for measuring patient weight to providers who met tuberculosis (TB) case identification and registration goals. In townships with these (essentially) nonfinancial incentives, identification of TB cases rose by 30% points relative to informal comparison townships. Anecdotal reports suggest that Zambian health workers participating in an incentive program (rewarding malaria treatment, infant and maternal care, and childhood immunizations) responded more favorably to trophies than to cash incentives. Finally, case studies suggest that health providers rewarded for good performance with t-shirts, badges and certificates, and recognition photographs may have been successful.

One rigorous quantitative study concurs with this qualitative and anecdotal evidence. In studying Zambian hair stylists with financial and nonfinancial incentives to sell condoms to salon clients, researchers found that public recognition outperforms monetary incentives. These results are heterogeneous across stylists and are largely due to strong behavioral responses among stylists believed to be more committed to the cause of HIV prevention.

Perverse Incentives And Unintended Consequences

The use of incentives to improve health program performance is fraught with the possibility of unintended and potentially perverse consequences. This section discusses some of these concerns and describe the empirical literature related to each.

Noncontracted Outcomes

One type of unintended behavioral response to performance incentives has been studied in the theoretical literature on ‘multitasking.’ When agents are responsible for multiple tasks or multidimensional tasks (some of which are unobservable or noncontractible), rewarding performance on a subset of contractible tasks or outcomes can lead to a reduction in effort devoted to noncontracted outcomes. The degree to which this occurs may depend in part on the extent to which noncontracted outcomes share inputs with contracted outcomes.

Empirically, some studies of performance incentives have found evidence of such behavioral distortions. A Kenyan school meal program rewarding improved pupil malnutrition rates found that subsidized meal preparation crowded out teaching time by 15%. Similarly, providing incentives to Chinese primary school principals for reductions in student anemia may also have displaced teaching effort, leading to lower test scores in some cases. Findings across empirical studies of performance incentives are heterogeneous, however. Several rigorous studies also report no clear evidence of distortionary or detrimental reallocation of effort or other resources in response to performance incentives.

Beyond the standard multitasking framework, performance incentives may lead to other closely related behavioral distortions. For example, although not studied empirically (to the best of our knowledge), performance incentives could lead to reallocation across multiple substitute activities related to the same disease or health outcome – or even the purposeful neglect of one to earn higher rewards for another (rewarding the successful treatment of a disease would undermine incentives to prevent it). Given the growing emphasis on ‘impact evaluation,’ another related example would be distortionary reallocation of effort and resources toward an evaluation’s primary outcomes (and away from outcomes not emphasized by the evaluation). As demonstrating ‘impact’ can lead to new or continued funding, the evaluation process itself may therefore create important behavioral distortions (depending on the beliefs of the evaluated organization).

Heterogeneity In The Return To Effort Across Contracted Outcomes

Among contracted outcomes, providers may also allocate effort to those that yield the largest (net) marginal return. In Rwanda, researchers found that rewards for good performance were most effective in improving outcomes that appear to have the highest marginal return or require the least effort. For example, performance incentives were more effective in increasing institutional delivery rates among pregnant women already in contact with community health workers (a relatively easy task because new patient relationships did not have to be created) than they were in initiating the use of early prenatal care (which the researchers suggest to be a relatively difficult task because doing so requires early identification of pregnant women not yet in contact with the health care system). Moreover, the incremental payment for institutional deliveries was relatively high (US$4.59), whereas the incremental payment for completion of quarterly prenatal care visits was relatively low (US$0.09). Ultimately, institutional delivery rates rose by more than 20% points, but there were no increases in the share of women completing all quarterly prenatal care visits.

Patient/Subpopulation Selection

In addition to altering how providers choose among tasks, performance incentives may also influence how providers allocate effort among patients or community members. Although not the focus of our review, incentives for patient selection are a ubiquitous concern with the use of high-powered incentives that emphasize cost containment (e.g., capitated contracts under managed care in wealthy countries). With performance incentives for good patient outcomes, selection against the sickest or most remote patients (‘cherry picking’) may occur if producing contracted outcomes among them is relatively difficult or costly.

Performance could alternatively be linked to population rather than patient outcomes, but providers could then be discouraged from providing services to individuals outside of the predefined population. Similarly, they may simply focus on the easiest to treat subpopulations within their defined service area. Some pay-for-performance schemes have tried to limit perverse incentive like these by offering larger rewards for services provided in more difficult or remote areas. Although such design features may reduce incentives for selection, eliminating them is a nearly impossible task (as the literature on risk adjustment suggests).

Erosion Of Intrinsic Motivation

Finally, pay-for-performance incentives may have unintended consequences for the institutional culture of health care organizations and for the intrinsic motivation of individual providers. One study develops a model in which effort in the presence of rewards is a function of intrinsic motivation (operationalized as altruism, but which could also include pride in one’s work, etc.), extrinsic motivation (material self-interest), and ‘reputational’ motivation (related to socialor self-image). In the model, monetary rewards undermine ‘reputational’ motivation and can therefore crowd-out effort by changing the perceived meaning of one’s actions (an ‘image-spoiling’ effect). Both laboratory and field evidence lend some empirical support to this prediction. In one experiment asking students to perform an altruistic task (collecting charitable donations), evidence suggests that the net effect of small monetary incentives on prosocial effort is negative – students put more effort into the task when they were not compensated than they did when offered a small incentive.

In low- and middle-income countries, there is similar concern that the use of financial incentives may lead to demoralization (due to perceptions of ‘bureaucratization’), reductions in intrinsic motivation, and less trust between patients and providers. Over time, the quality of individuals entering the public health workforce could also decline if the use of financial incentives selects against intrinsically motivated health care workers.

Even if extrinsic incentives appear to work in the short run, the errosion of intrinsic motivation can still be a longer-run concern. Psychology experiments suggest that individuals offered monetary incentives to perform an otherwise intrinisically rewarding task put substantially less effort into the task (compared with control groups) when the incentives were removed. This has been attributed to the effect of extrinsic rewards on individuals’ perception of themselves, on the value of the rewarded task, and on social perceptions of the task. Although not yet studied in low- and middle-income country health programs, one study of performance pay in the US (at Kaiser Permanente Hospitals) supports these findings.

Conclusion

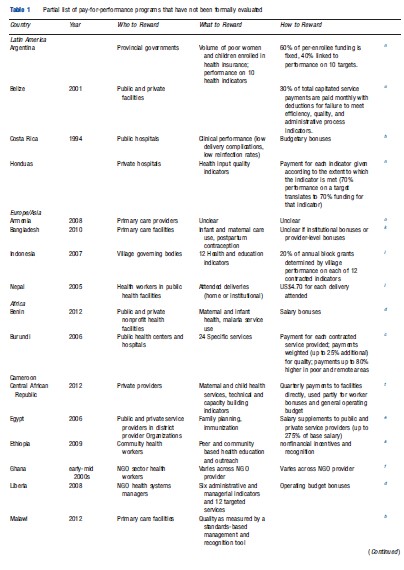

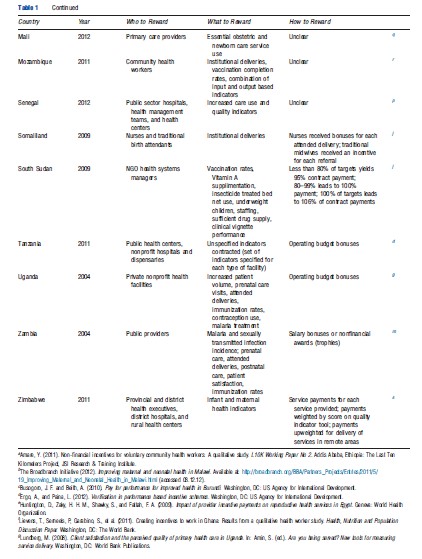

This article summarizes important conceptual issues in the design of pay-for-performance incentive schemes. These include choice of contracted outcomes, the organizational level at which to offer incentives, the structure of incentive contracts, and what the unintended consequences of performance pay might be. In doing so, the existing peer-reviewed evidence related (in varying degrees) to each was also surveyed. The authors highlight that despite the growing body of research on performance incentives, very little of it has studied the underlying conceptual issues that are outlines (which is critical for the design of better performance incentives). It is also noted that evaluation has not kept pace with growth in the use of performance pay: Table 1 lists the programs that have not been studied (or studied rigorously) to the best of our knowledge. Strategically selected empirical research on these unstudied programs may provide a low-cost way of strengthening the body of evidence on foundational issues inherent in the design of performance incentives. In the conclusion, we also raise additional issues about which little is known.

The first is that there is substantial heterogeneity in responses to performance pay both across and within programs. The authors therefore caution against direct comparison of pay-for-performance schemes across different organizational, social, and institutional environments. However, it is also noted that understanding the underlying sources of this heterogeneity may provide insight into the circumstances under which performance pay is more or less effective (or socially desirable) too. For example, lack of autonomy among providers or health care organizations may be a critical obstacle to the effective use of performance pay in the public sector (because it restricts the range of behavioral responses that are possible).

Performance incentives may also interact with the preexisting incentives and social norms in important ways. In one study, the impact of performance pay varied across incentivized agents by a factor of three or more (and the underlying source of heterogeneity was not strongly correlated with demographic and socioeconomic characteristics). Another found that provider responses to performance pay varied significantly by baseline provider quality indicators. More generally, adequate bureaucratic capacity to enforce contracts, collect data, and verify performance is presumably necessary for pay-for-performance schemes to succeed. Analysis of heterogeneous responses to performance incentives is an important area for future research.

Second, pay-for-performance schemes may have important equity implications. Given that the net return to provider effort will undoubtedly vary across activities and subpopulations, performance pay may lead providers to focus on individuals with varying socioeconomic or health characteristics. Pay-for-performance contracts offered to village governments in Indonesia attempted to address this concern by allocating equal performance pay budgets across geographic regions with varying socioeconomic characteristics (to prevent some regions from benefitting disproportionately from the performance scheme). Competition among villages for performance rewards therefore occurred within, but not across, regions.

Finally, there has been surprisingly little rigorous empirical evaluation of the full welfare consequences of performance pay. The necessary building blocks for a cost–benefit analysis include a full understanding of the behavioral responses to performance pay and their magnitudes (including unintended ones) and a method for valuing each in common (typically monetary) units. Such evaluations are critical for understanding the ultimate social desirability of pay-for-performance schemes.

References:

- Ashraf, N., Bandiera, O. and Jack, K. (2012). No margin, no mission? A field experiment on incentives for pro-social tasks. Working Paper. Cambridge: Harvard Business School.

- Basinga, P., Gertler, P. J., Binagwaho, A., et al. (2011). Effect on maternal and child health services in Rwanda of payment to primary health-care providers for performance: An impact evaluation. Lancet 377(9775), 1421–1428.

- Bloom, E., Bhushan, I., Clingingsmith, D., et al. (2006). Contracting for health: Evidence from Cambodia. Cambridge: Harvard University.

- Das, J. and Hammer, J. (2007). Money for nothing: The dire straits of medical practice in Delhi, India. Journal of development economics 83(1), 1–36.

- Eichler, R. and Levine, R. (eds.) (2009). Performance incentives for global health: Potential and pitfalls. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development.

- Ellis, R. P. and McGuire, T. G. (1993). Supply-side and demand-side cost sharing in health care. Journal of Economic Perspectives 7(4), 135–151.

- Gertler, P. and Vermeersch, C. (2012). Using performance incentives to improve health outcomes. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 6100, Impact Evaluation Series No. 60. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Gneezy, U., Meier, S. and Rey-Biel, P. (2011). When and why incentives (don’t) work to modify behavior. Journal of Economic Perspectives 25(4), 191–209.

- Holmstrom, B. and Milgrom, P. (1991). Multitask principal-agent analyses: Incentive contracts, asset ownership, and job design. Journal of Law, Economics & Organization 7, 24–52.

- Loevinsohn, B. and Harding, A. (2005). Buying results? Contracting for health service delivery in developing countries. Lancet 366(9486), 676–681.

- Miller, G., Luo, R., Zhang, L., et al. (2012). Effectiveness of provider incentives for anaemia reduction in rural China: A cluster randomised trial. British Medical Journal 345, e4809.

- Olken, B. A., Onishi, J. and Wong, S. (2012). Should Aid Reward Performance? Evidence from a field experiment on health and education in Indonesia. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper, w17892. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Singh, P. (2011). Performance pay and information: Reducing child malnutrition in urban slums. MPRA Working Paper. Munich: Munich Personal RePEc Archive.

- Soeters, R., Peerenboom, P. B., Mushagalusa, P. and Kimanuka, C. (2011). Performance-based financing experiment improved health care in the democratic republic of Congo. Health Affairs 30(8), 1518–1527.

- Witter, S., Fretheim, A., Kessy, F. L. and Lindahl, A. K. (2012). Paying for performance to improve the delivery of health interventions in low-and middleincome countries. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Issue 2 Art. No.: CD007899. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007899.pub2.