Introduction

The defining feature of health care markets and the economics of the health care sector is information structure. Kenneth Arrow, in his seminal paper, demonstrates the role that ‘missing markets’ for information play in explaining the existence of the features of health care that distinguish it from other industries and markets (Arrow, 1963). Information structure can explain not-for-profit firms, widespread insurance coverage, and the role of physician agents who both proffer advice on treatments and sell those same services, amongst other unique features. The importance of these missing markets become clear if one considers a ‘simple’ market for health care services. At almost every turn a consumer faces a substantial if not (at least privately) insurmountable level of uncertainty in decision making.

Picking between health insurance plans, in principal, requires a clear sense of the value of a particular plan in the event that a person becomes ill with a specific disease. What hospitals and doctors would be available? At what cost? Even with all of this information in hand the choice of plan requires that each eventuality, and the associated care available, be weighed taking into account the probability that a particular disease occurs. Once equipped with coverage, the individual must then choose a primary care physician. The hope is that this physician will provide preventive care to manage the totality of the patients health, skillfully diagnose the universe of possible ailments and, should the patient require more specialized care, recommend and support the choice of a specialist and the assessment of their treatment plan. A specific physician may differ in skill across each of these margins. As with insurance, the choice is made without knowing precisely which health issues even might occur and, therefore, which skills are most valuable. If the consumer then requires more intensive treatment, they must choose a specialist. To accomplish this they must, under the duress of illness, try to assess the quality of a particular specialist as well the efficacy of a given treatment approach.

This stylized depiction makes clear how health care decisions made by the consumer are potentially rife with information problems. In light of these informational challenges, in health care how do we think about the basic building block of economics: the demand curve? Perhaps more importantly, from an economists perspective, how do we think about welfare and market function in a market where demand is determined in this manner? (Congdon et al. (2011) discuss issues of decision making in an environment with informational constraints and decision makers with nonstandard preference. They demonstrate the importance of these issues with respect to the theory of welfare and social choice as well as their potential role in public policy.)

Moving from theory to practice, information plays a key role in public policy. Many of the policy approaches to address the perceived quality and cost issues in the health care market rely on, either explicitly or implicitly, attempting to address the information asymmetries in the market. The best known and most studied of these efforts are the provision of information directly to consumers. This article focuses on the experience of using direct information provision to overcome market failures in the market for health care services. Specifically, the focus will be on the provision of quality information and its impact on demand.

The author begins by developing a simple, stylized model of supply and demand to demonstrate the role of information in market function in health care. Then some extensions are introduced to allow for insurance and uncertainty. With the simple economics of quality reporting and demand as a framework, the role of quality information and quality reporting in provider choice is then discussed. The choice of primary care physician is distinguished from specialists and hospital choice as they are distinct choice environments, each yielding unique market failures and potential for market based or policy solutions. Rather than review the complete literature on quality reporting and demand for specialists, thefocus is on the experience in the market for coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery. This market is the oldest and most studied of the applications of quality reporting. The main issues and empirical conclusions can be drawn from the experience in this market. Then the experience of quality reporting in the CABG market is compared to similar efforts in education. This comparison demonstrates the similarities between the fields in the information structure, and its associated market failures, as well as the impact of quality reporting.

Quality Information And Quality Of Care

Baseline Model

To frame the discussion of quality information and demand, the author begins by developing a stylized model of the market for healthcare services. Demand is determined by a set of consumers who choose healthcare providers based on their utility from a specific provider relative to another as well as the gain from getting care at all relative to foregoing care. These consumers care about the price they pay for care and the quality of care provided. Quality in this context can be multidimensional. Patients care about the clinical quality of care they receive (e.g., lower chance of getting an infection from hospital care or lower probability of mortality from bypass surgery) and how satisfied they are with their experience and nonhealth amenities (e.g., the comfort of their bed, the quality of food, or the cleanliness of the waiting room).

The supply of healthcare services consists of healthcare providers who determine the quality of care provided by making costly investments to enhance care delivery. For simplicity, assume these investments are a continuous, convex cost function, though the basic intuition holds in different contexts. In the standard model healthcare providers care only about the profit they gain – the price per patient times the number of patients less the cost of supplying healthcare at a given quality level.

This stylized model of the doctor, patient relationship is the workhorse of health economics and adheres closely to the conventional market model that economists rely on in most markets. In this setup the quality and price of healthcare are determined where the supply of care equals demand for care. Importantly, for the present purpose, this model also provides insight into the level of quality selected by the doctor. How this level is determined has both normative and positive implications for the function of healthcare markets and the role of quality reporting in demand.

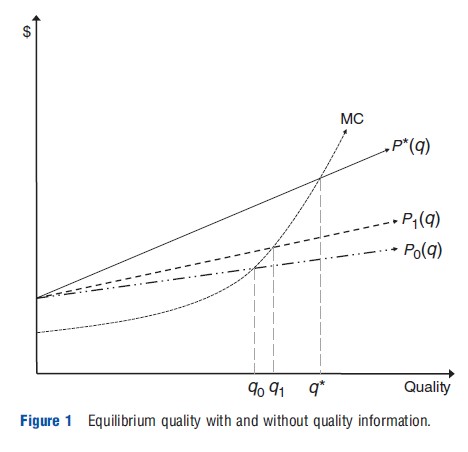

To see this, consider a provider choosing a level of quality. Figure 1 presents this simple example graphically. In the standard model, the profit maximizing provider chooses his optimal quality based on the marginal cost of increasing quality of the good (i.e., time spent with the patient assessing their ailment or additional surgical nurses to support him during surgery) and marginal revenue from the improved quality. This point is q where the baseline marginal revenue curve (P (q)) equals marginal cost. As long as consumers can ascertain each provider’s quality, they choose the provider that provides them the greatest gain in utility – quality less the price of care. The doctors, who observe their own and their competitor’s quality as well as the response of the market to quality, then face a simple optimization; the doctors choose a level of quality investment such that the marginal cost of quality improvement is just equal to the marginal revenue associated with that quality improvement – the additional patients scaled by the profitability of those patients.

This baseline model provides clear positive and normative predictions for the quality and cost of healthcare. Because the competitive supply and demand conditions are met both the first and second welfare theorems hold and the quality and cost of care cannot be improved on without making some individuals worse off (Arrow, 1963). That is, the effort to maximize profit would yield productive and allocative efficiency in the market for healthcare services. Doctors would deploy resources to minimize the cost of supplying quality given the input prices to produce quality (e.g., the wages of additional surgical nurses). Furthermore, the level of healthcare quality supplied would reflect societies underlying preference for healthcare quality, relative to other forms of consumption. (A number of papers have estimated these preference and suggest a relatively high willingness to pay for health improvements (e.g., Cutler, 2003; Murphy and Topel, 2006). With diminishing marginal returns to consumption, this willingness to pay is also increasing in income (Hall and Jones, 2005). These estimates can explain much of the high spending in many developed countries as well the focus on quality of care and technological improvement. The author returns to this issue in considering whether demand with limited information is lower than what the true demand would be expected to be.) That is, the well documented quality issues in healthcare as well as the high cost and reliance on technologically intensive provision of healthcare, particularly in the USA, would not pose a public policy concern.

There are many reasons to doubt the market for healthcare services meets these stringent criteria for market function. One important and pervasive deviation is the presence of adverse selection – another market failure due to information asymmetries. Because consumers differ in profitability (difficulty to treat relative to a fixed payment), even if the respond to quality information providers have an incentive to distort their quality investments to attract relatively more profitable patients. Thus, even with full quality information the equilibrium may not be a first best (Rothschild and Stiglitz, 1976; Glazer and McGuire, 2005). (In practice, enhancing consumer choices can exacerbate adverse selection problems further. Handel (in press) documents this effect empirically in the market for health insurance. Alternatively, appropriately structured information provision can induce first best effort even in the presence of adverse selection (Glazer and McGuire, 2005; Glazer et al., 2008).) Nevertheless, the author starts with this stylized benchmark model because it provides a clear insight into how and why economists and policy makers might expect quality reporting and associated changes in demand to correct market failures in healthcare.

Arguably the single largest violation of the necessary conditions in the benchmark model is the information asymmetry between consumers of healthcare services and producers. In very few cases does an unaided consumer have a good sense of the quality of his or her doctor relative to alternate physicians that might be available or even relative to outside options of a different treatment regime or no treatment at all. Where this is true, a provider who invests in improving the quality of care provided will see few additional patients and, therefore, little additional profit. This is represented by the inverse demand curve (P0(q)) in Figure 1 that maps quality into a price consumers are willing to pay. P0(q) is below the full information benchmark curve, P *(q). Because the provider chooses quality based on trading off the cost of quality improvement compared to the marginal revenue from quality improvement, the equilibrium quality level will be lower than it would otherwise be, q0 in Figure 1. This is not only a positive observation that quality is lower but it also means that the level of quality is suboptimal in a normative sense. The information problems mean that demand does not reflect the true willingness to pay for quality and therefore the market does not supply the socially optimal level of quality. This can be seen by simply comparing the equilibrium quality under P*(q) (q*) to the lower level under P0(q) (q0). This basic concern is, either explicitly or more often implicitly, underlying concerns about quality of care provided in most healthcare markets (IOM, 1999).

Quality Reporting To Address The Missing Market For Information

Because asymmetric information is at the heart of the market failure, a natural approach to improving healthcare quality is to try to supply more information to the market actors who are at a relative disadvantage, in this case consumers. Information provision can occur through market-based intermediaries (e.g., consumer reports for consumer products, Yelp for restaurants, or Angies List for skilled professionals including doctors) or as information-based public policy in which government agencies or public–private partnerships gather and disseminate quality information. In both cases, the hope is that consumers will be able to obtain the necessary information to determine the quality of each available healthcare provider and then determine which doctor to choose, given both the cost and the quality of care they will receive. The effect of an intervention of this type can be seen in Figure 1 if the change in marginal revenue from quality after reporting is taken into consideration, represented by P1(q). Because the information asymmetry has been reduced, it is more profitable to improve quality and the demand curve has rotated upward. As this tracks along the marginal cost of quality improvement a new equilibrium quality level that is higher is reached, q1. Whether the information is sufficient to overcome the universe of information problems depends on the degree to which P1(q) moves toward the social optimum, P*(q). In the example depicted, there remains a large gap both in the incentives (P1(q) versus P*(q)) and, subsequently, the equilibrium quality, (q1 vs. q*).

One appeal of this approach is that changes in quality of care are mediated solely through market incentives, rather than a regulator or payer determining how best to provide high quality healthcare and requiring that physicians practice in a particular manner. Instead, the newly informed consumers will reward the physicians who are best able to provide the quality of care they demand at the minimum cost. (Because demand was relatively unresponsive to quality in the absence of information, such an information intervention is expected to increase the quality of healthcare provided. To the extent that consumers face the true price of care, the improved quality will be unambiguously welfare enhancing.)

Prices And Insurance In Demand

An omnipresent concern in healthcare markets is not merely the information asymmetries in consumer choices but the fact that most consumers seeking care will have access to insurance and, therefore, are unlikely to face the full cost of their care at the margin (Pauly, 1968; Zeckhauser, 1970). The role of moral hazard in demand has important implications for quality reporting for two reasons. First, providing quality information to insured consumers need not enhance welfare even if quality was too low before the information intervention. Because consumers do not face the full cost of their care, they may demand too much quality and this could be exacerbated by the release of quality information. Before quality release the insured consumer was relatively unresponsive to price but could not distinguish high from low quality doctors. Therefore, profit maximizing providers set high prices relative to the cost of their quality, leading to not only inefficiently low quality but excess expenditures given the quality. Once reporting is introduced, the rewards for enhanced quality are greater because higher quality doctors gain more patients. However, because consumers do not face the full price of seeking higher quality care their demand for quality is even greater (they get all of the upside of quality but only pay a fraction of the additional cost). In this case, the introduction of quality information may excessively reward quality improvement relative to the social optimum leading to excessively high investment in quality improvement and, ultimately, quality (Gaynor, 2006; Dranove and Satterthwaite, 2000).

A related issue is the fact that many healthcare providers do not set prices in a standard marketplace. Rather they agree to provide services at an administered set of prices. This is certainly true for doctors and hospitals providing care to patients covered by public programs such as Medicare. Medicare sets prices for hospital services (diagnosis related groups) and physician services (resource based relative value units) based on an estimate for the cost of supplying that particular service. As in any administered price setting, providing appropriate incentives is a challenge (Newhouse, 2002). Because most private payers also base their negotiated price on the Medicare rates these choices not only affect the equilibrium quantity and quality for government paid patients but for the entire market. When prices are more than the marginal cost, the reward for gaining additional patients are large. This leads to the same phenomenon as with moral hazard among consumers. There is a greater reward for additional patients and, therefore, quality improvement. Conversely, when prices are set lower than marginal revenue, administered pricing can lead to inefficiently low quality and reduce incentives for quality improvement associated with shifts in demand. Thus, the introduction of quality reporting in a market with administered prices above cost will yield improve quality of care but may also encourage excess investments beyond the social optimum and vice versa. Clearly there is a relationship here between two policy tools: information provision and the payment rate. If the payer is able to set the appropriate payment such that reimbursement for the marginal patient is just equal to the marginal valuation for quality or care and the marginal cost of quality, the combination of public reporting and payments can provide the first best quality level. (Determining the appropriate marginal patient also poses a challenge. The social planner cares about the average marginal patient but the optimizing provider cares about the marginal patient (Spence, 1980). In this case there can be a further wedge driven between social optimum and competitive equilibrium quality.)

Uncertainty

As with much of healthcare (not to mention other markets), this is easier assumed than done. Distortions to this choice process arise because consumers are typically insured, face uncertain tradeoffs between treatment options and, perhaps most importantly, generally cannot verify the quality of care they received or the quality of different provider options available. Although all of these features contribute to market outcomes in markets for healthcare providers, this article concentrates on the latter: the role of asymmetric quality information and the policy options to address this in determining healthcare quality.

Suppose that consumers (patients) choosing a physician care about three different attributes: price, clinical quality, and amenities. This simplifies the discussion but captures the most salient features of the policy debate regarding cost and quality of healthcare. Dranove and Satterwaite (1992) and Dranove and Satterthwaite (2000) demonstrate the key role that uncertainty plays in determining the level of each attribute and the interaction of consumer preference and knowledge about each. Although both papers develop technical detail necessary to solve the problem, some simple predictions emerge that motivate this discussion of quality information. If patients are uncertain about two attributes, they will tend to overweigh the observation that is more certain and underweigh the less certain attribute. Translating this into the incentives facing suppliers of care, the relatively observed measure is expected to have excessive investments in improvement and the converse for the relatively harder to observe provider attribute.

This finding is of particular concern in healthcare markets where clinical measure of performance are generally characterized by uncertainty but service amenities are far easier to observe. This is true in the absence of report cards; physicians and hospitals will invest in amenities excessively relatively to efforts to improve clinical quality. For example, hospitals have, for a long time, provided well-appointed entryways and valet parking but their attention to regular hand washing and infection control is a far more recent effort (arguably brought about by Medicare payments not demand changes) (Goldman et al., 2010). It is also relevant in the response to report cards. If quality reporting includes satisfaction or service metrics as well as harder to interpret clinical measures, quality reporting might exacerbate the relative focus on service as opposed to clinical quality.

Evidence On Quality Reporting And Demand

Quality And Demand For Primary Care Physicians

For most patients, their first point of contact with the healthcare system is through their primary care physician. The choice of and role for the primary care doctor distinguishes this choice when quality reporting and demand is considered. Specifically, defining high quality primary care is a challenge and determining what information patients might use to choose a primary care doctor also poses an issue.

Choice of a primary care doctor exhibits the universe of choice problems that characterize demand in healthcare. Quality is highly uncertain and depends on the health of the patient. Jointness in production is also key. A primary care doctor is there to treat conditions but, particularly for patients with chronic conditions, the doctor is likely to suggest complementary behaviors by the patient that are as (if not more) important for improving health. A high quality doctor treating a diabetic patient could screen for the level of sugar in the blood (the HBalC test) but this is not, in and of itself, a treatment for any of the ailments of diabetes. Instead, this measure will allow the physician to adjust medications to manage the disease but also to help council the patients on how they should change their eating habits.

Even when there is a reasonable measure of disease, as in the case of a diabetic patient, defining end points the characterize a high quality primary care doctor is a challenge. Ideally, most patients are healthy and remain so. Attributing the fact that a patient becomes ill to low quality primary care though would not produce the right incentives. Everyone will become ill at one point; death along with taxes are certain in this life. Furthermore, a patient who is identified as becoming ill may have received better care from their primary care doctor because the disease was found.

All of these factors make the introduction of quality report cards for primary care doctors a particular challenge. Instead, most quality reporting efforts in the primary care arena have been focused either on identifying high quality production and documenting such process measures or paying for those measures directly (e.g., pay-for-performance). Some forms of quality information on primary care physicians is becoming widely available through market-based information such as Angie’s List. These tools aggregate assessments of physicians quality from customer responses. This form of quality reporting is less studied but presents an important challenge to providing the appropriate social incentives for quality improvement (e.g., whether and how to weigh satisfaction relative to clinical quality depends critically on the form of the production function, consumer tastes and own, and cross quality elasticities with respect to these measures). Recall the results from Dranove and Satterthwaite (2000) discussed above. If people can observe patient satisfaction with relative ease but have a much harder time determining clinical quality or diagnostic ability, these tools may lead to an excess investment in patient satisfaction and an underinvestment in clinical quality. Of course, patients may truly value satisfaction in which case the emphasis on clinical quality could be unfounded. There is, however, ample reason to believe that information problems as well as myriad choice errors documented in behavioral economics are likely to lead to suboptimal choices with respect to clinical quality (Frank, 2004).

Quality Reporting And Specialist Choice

The role of quality information and quality reporting in choice of specialists is the most studied of any of the ways information might impact demand. Specialist choice is also the area in which information-based policy could have the biggest impact on welfare. Specialists perform specific and often measurable tasks. They also encounter patients when they are sick and receiving the most intensive care; precisely where one might expect quality improvement to enhance outcomes. There is a voluminous empirical literature focused on the response to quality information on specialists. Rather than surveying the literature, a task that has been done in a number of other settings (see, e.g., Kolstad and Chernew, 2008 and Dranove and Jin, 2010 for recent reviews), the focus here is on a specific setting: the introduction of quality report cards in the market for CABG surgery. Though quite specific, the CABG case is the most studied quality reporting initiative. Furthermore, the results, methodologies, and issues are, generally, indicative of the broader findings on the role of quality reporting and demand.

Beginning in 1988, New York State gathered and reported hospital-level risk adjusted mortality rates (RAMR) for CABG surgery. Shortly thereafter, following freedom of information request, surgeon-specific RAMR was reported beginning in 1991. Pennsylvania followed suit shortly thereafter, initially introducing quality report cards in 1993, though report cards were not widely available until 1998 when reports based on 1994–95 data were disseminated. Subsequently, many more states and countries have begun to provide CABG quality report cards. As of 2006, 47 states and the UK all offered CABG report cards (Steinbrook, 2006).

There are two broad veins of literature that provide insight in the CABG surgery experience with quality reporting: survey based and actual choice based. Mukamel and Mushlin (1998) find that both hospitals and doctors with better RAMR saw an increase in market share following the release of quality reporting. Culter et al. (2004) also study the New York experience. Their paper extends the basic test for an effect of market share in two important directions. They allow for heterogeneous response to RAMR depending on whether a hospital is above or below expected. They also compare the response of patients who are more likely to be able to switch surgeons, those that are less severe. Their results suggest a significant response to hospitals that are flagged as high mortality (lower quality) than expected. They find a high mortality designation is associated with an average decline of 5 CABG surgeries per month, or approximately 10% of a hospital’s volume. Interestingly, they do not find a commensurate increase in demand for hospitals identified as a lower than expect mortality (high quality). The response to quality information is almost entirely driven by changes among patients who are relatively healthy; presumably the patients who have the time and opportunity to choose between hospitals. Dranove and Sfekas (2008) also study the response to the release of quality report cards. Their model makes an important contribution by accounting for prior beliefs of consumers. That is, if consumers or referring physicians already know a hospital is of high quality, one would not expect much effect of releasing information on market share. As in Culter et al. (2004), they find that demand responds more strongly to quality information after accounting for prior market-based learning. They also find that there is an asymmetric response with patients more responsive to learning a hospital is of lower than expected quality than to learning a hospital is better than expected. Kolstad (2012) also studies the demand response to quality reporting for CABG surgery, in Pennsylvania in this case. The distinction of this model, with respect to understanding demand, is that it allows for taste heterogeneity among consumers. As with the earlier literature, he finds a significant response to quality after the release of quality report cards. This effect varies significantly in the population with a small share of the population responding very strongly to quality after report cards.

Survey-based evidence also suggests an effect of report cards on demand, though these studies generally find little impact on actual patients with more impact on referring cardiologists. Schneider and Epstein (1996) address this question directly by surveying cardiologists in Pennsylvania. They find that roughly 10% of cardiologists found quality information very important. In New York State, Hannan et al. (1996) conducted a similar survey of cardiologists finding a larger response; 38% of cardiologists report that the report card’s their referral pattern. A relatively strong responsive of a minority of referring physicians is consistent with the higher-level empirical results that find a similar observed response.

Taken together, these results are indicative of many of the findings in the literature on quality reporting and demand for specialists. First, quality reporting has a small but significant effect on demand. Second, this effect is convex in quality – consumers seem more willing to pay (travel) to avoid low quality specialists than they are to access high quality specialists, even though the change in quality is the same in both cases. Third, there is substantial heterogeneity in the population in whether and how patients respond to the information. A small minority of patients respond strongly by switching hospitals and surgeons but there is relatively little movement by the bulk of the patient population. Fourth, physician agents and/or existing market-based learning means that higher quality providers tend to have greater demand even before the release of report cards. This has the effect both of muting the estimated response to quality information release and suggesting that the institutions of the healthcare market are able to inform consumers somewhat without intervention.

Quality Information And Supply

The focus of this article is on the role of quality information in demand. However, the process of gathering, analyzing, and synthesizing quality information also has the potential to inform suppliers, in this case physicians and hospitals. If these efforts both provide new information and inform suppliers who care about quality beyond the pecuniary rewards, then quality reporting can impact outcomes without shifting demand. How and why this process occurs is a new and relatively unexplored area of research on quality reporting and outcomes. However, Kolstad (2012) demonstrates that, in the market for CABG surgery in Pennsylvania, the impact of information provided to suppliers had an effect on quality improvement that was four times larger than the impact mediated through changes in demand, the type of impact focused on primarily in this discussion. In this model, new information impacts physicians because they care intrinsically about supplying high quality care and quality reporting allows them to better observe their performance relative to their peers. A detailed case study of the impact of New York State’s CABG reporting program also provides anecdotal evidence for a very similar impact. Dziuban et al. (2008) document the important role that the release of quality report cards had in motivating efforts to improve the process of care to lower mortality at a large community hospital. Interestingly, they find that the new information led to large changes despite the fact that the hospital had a detailed data capture and outcome review process in place beforehand. This underscores potentially important features that usually characterizes quality reporting: volume and scope of observations and risk adjustment. If quality reporting efforts gather data from across settings (e.g., hospitals or health systems) and develop stateof-the-art risk adjustment models they are likely to provide new information to providers, even if those providers have local monitoring tools in place (e.g., electronic health records or ‘morbidity and mortality’ conferences to discuss quality and errors). These issues are key to understanding the aggregate role that quality reporting and quality information might play in market outcomes and quality of care. The precise model of beliefs and preference, however, that leads quality information to affect supplier behavior remains an outstanding question.

Another important supply side response to quality reporting that has been much discussed is the potential for providers to try to select healthier patients to improve their scores. The inclusion of risk-adjustment is intended to address this issue. With sufficiently good risk-adjustment the incentives for selection are eliminated. In practice, however, this is extremely difficult if not impossible. In the absence of perfect risk-adjustment, one must consider the trade-off between selection incentives and the gains in welfare associated with quality improvements due to information. This underscores the fact that the existence of selection against sicker patients does not, in and of itself, eliminate the value of quality reporting efforts. It does, however, raise important welfare tradeoffs and require some consideration of the distributional impacts of quality reporting across the spectrum of patients. Despite a great deal of hypothesizing about selection efforts, there are relatively few empirical studies that document selection in response to report cards. The most prominent is work by Dranove et al. (2003). They study the impact of New York’s and Pennsylvania’s introduction of CABG quality reporting in the Medicare population. They find evidence that quality reporting enhanced patient matching to surgeons and hospitals and that there was selection against sicker patients. The aggregate impact of quality reporting was to reduce welfare – the losses from selection outweighed the gains from reduced information asymmetries. This article raises important issues and also presents a useful methodology for evaluating quality reporting efforts.

Quality Reporting And Demand In Other Markets: Comparing Healthcare To Education

Healthcare is one of a number of important fields in which information-based public policy plays a role. It is informative to compare the experience in other markets as a benchmark for understanding the impact of quality reporting on demand. Education provides a useful comparison. There are a number of similarities between choices of healthcare providers and choices of schools that both rationalize the reliance on information-based public policy and make a comparison between the two fruitful. In both cases, information asymmetries are a defining feature of demand. In both cases, consumers are being asked to choose between different suppliers with difficult to verify differences in skills and quality. Outcomes are also characterized by joint production. How much students learn is affected both by teacher effort and student effort. Similarly, the efficacy of many treatments – particularly those for chronic conditions – rely on physician effort as well as patient’s willingness to follow advice and change behavior. In both cases, there is also an important component of random noise in outcomes and incentives to teach to the test or select healthy patients. Finally, in both markets the externalities associated with providing the good mean that public provision is preferred and, therefore, most consumers face little, if any, price variation.

So how does the experience with quality reporting in education compare to the CABG market? The main findings appear to be similar, though it is noted this is far from a complete review of the education literature. Hastings and Weinstein (2006) study the response of parents and students to the public provision of information on school quality. They find a significant response to the information on school quality, measured by test scores. After information is released parents are more likely to choose a higher quality school by 5.7 percentage points. They also find that attending a higher quality school improves student test scores. Glazerman (1998) studies school choice and finds that consumers are highly responsive to distance. The effect of quality on choice is diminished substantially as higher quality schools are further away. Hanuscheka et al. (2007) study the release of quality information for Texas charter schools. They find that the release of quality information increases the likelihood that low quality schools exit the market significantly.

Although clearly not a comprehensive review, these important papers demonstrate some striking similarities to the role of quality reporting in healthcare markets. First, there appears to be a substantial response to quality reporting, though this effect is relatively small. Consider the main estimate from Hastings and Weinstein (2008). They find that roughly 1 in 20 parents was responsive to quality information. Comparing this to the response in Culter et al. (2004) this is a similar magnitude, though smaller, than the response to quality reporting for CABG in New York State. There hospitals saw a decline in volume in the year following a high mortality flag of 10%. Similarly, the findings that distance seems to weigh very strongly in the choice of schools is quite similar to healthcare demand. Both industries are characterized by local markets but it is striking that the healthcare consumers who generally make far fewer trips to a hospital are so responsive to distance. It is less surprising, given the daily trips to school, that distance has an effect. That said, in both cases one would expect the utility for a good outcome (e.g., lower mortality or morbidity and improved lifetime earnings) to be very high so substantial distance effects are surprising and potentially indicative of information problems that limit the response to high quality.

Conclusion

In this article the basic theoretical underpinnings for quality reporting and demand in healthcare markets have been covered. The rationale for quality reporting is based on the potential for asymmetric information on quality that leads to suboptimal outcomes. It has been seen, in a simple framework, how changes in demand due to information provision can change equilibrium quality. Whether these changes improve welfare depends on a number of features of the market. Ultimately, however, the normative standard is the full information demand curve that would exist. The empirical evidence on the impact of quality reporting on demand suggests small average effects with important heterogeneity in the population. Comparing the estimates to the impact of quality reporting in education suggests the impact of quality reporting in cardiac surgery has been larger.

Despite the many simple empirical studies of quality reporting and demand, the application of econometric tools and field experiments to better understand the precise mechanism by which quality reporting improves quality is an important next step for research. For example, incorporating the supply side response into the evaluation of the policy dramatically alters the way in which quality reporting policies should be evaluated as well as the way in which these interventions should be structured (e.g., should information be simplified to target consumers or made more clinically relevant for physicians?). As health reforms in the USA and the inevitable efforts to address cost and quality in all healthcare systems move forward, there is a key role for addressing information failures. Further understanding of the impact of quality information on demand and on market outcomes should be a key item on the research agenda in economics and health services research and an area of focus for policy makers for many years to come.

Bibliography:

- Arrow, K. (1963). Uncertainty and the welfare economics of medical care. American Economic Review 53, 941–973.

- Congdon, W., Kling, J. and Mullainathan, S. (2011). Policy and choice: Public finance through the lens of behavioral economics. Washington, DC: Brookings Inst Press.

- Cutler, D. (2003). Your money or your life: Strong medicine for America’s health care system. USA: Oxford University Press.

- Culter, D., Huckman, R. and Landrum, M. B. (2004). The role of information in medical markets: An analysis of publicly reported outcomes in cardiac surgery. American Economic Review (Papers and Proceedings) 194(2), 342–346.

- Dranove, D. and Jin, G. (2010). Quality disclosure and certification: Theory and practice. Journal of Economic Literature 48(4), 935–963.

- Dranove, D., Kessler, D., McClellan, M. and Satterthwaite, M. (2003). Is more information better? The effects of ‘report cards’ on health care providers. Journal of Political Economy lll(3), 555–558.

- Dranove, D. and Satterthwaite, M. (1992). Monopolistic competition when price and quality and imperfectly observable. The RAND Journal of Economics 23(4), 518–535.

- Dranove, D. and Satterthwaite, M. (2000). The industrial organization of health care markets, ch 20. North Holland: Elsevier.

- Dranove, D. and Sfekas, A. (2008). Start spreading the news: A structural estimate of the effects of New York hospital report cards. Journal of Health Economics 27(5), 1201–1207.

- Dziuban, S., Mcllduff, J., Miller, S. and Dal Col, R. (2008). Start spreading the news: A structural estimate of the effects of New York hospital report cards. Journal of Health Economics 27(5), 1201–1207.

- Frank, R. (2004). Behavioral economics and health economics. NBER Working

- Paper (10881). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Gaynor, M. (2006). What do we know about competition in health care markets? NBER Working Paper (12031). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Glazer, J. and McGuire, T. (2005). Optimal quality reporting in markets for health plans. Journal of Health Economics 25, 295–310.

- Glazer, J., McGuire, T., Cao, Z. and Zaslavsky, A. (2008). Using global ratings of health plans to improve the quality of health care. Journal of Health Economics 27, 1182–1195.

- Glazerman, S. (1998). School quality and social stratification: The determinants and consequences of parental school choice. San Deigo, CA: ERIC.

- Goldman, D., Vaiana, M. and Romley, J. (2010). The emerging importance of patient amenities in hospital care. New England Journal of Medicine 363, 2185–2187.

- Hall, R. and Jones, C. (2005). The value of life and the rise in health spending. Quarterly Journal of Economics 122(l), 39–72.

- Handel, B. (in press). Adverse selection and inertia in health insurance markets: When nudging hurts. Mimeo, University of California.

- Hannan, E., Stone, C., Theodore, B. and DeBuono, B. (1996). Public release of cardiac surgery outcomes in New York: What do New York state cardiologists think of it? American Heart Journal 134(1), 55–61.

- Hanuscheka, E., Kainb, J. and Steven, G. (2007). Rivkinb an Gregory Branch. Charter school quality and parental decision making with school choice. Journal of Public Economics 91(5–6), 823–848.

- Hastings, J. and Weinstein, J. (2006). Information, school choice and academic achievement: Evidence from two experiments. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 123(4), 1378–1414.

- Hastings, J. and Weinstein, J. (2008). Information, school choice, and academic achievement: Evidence from two experiments. Quarterly Journal of Economics 123(4), 1373–1414.

- IOM (1999). To err is human: Building a safer health system. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine of the National Academics.

- Kolstad, J. (2012). Information and quality when motivation is intrinsic: Evidence from surgeon report cards. NBER Working Paper No. 18804. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Kolstad, J. and Chernew, M. (2008). Consumer decision making in the market for health insurance and health care services. Medical Care Research and Review 66(1), 28S–52S.

- Mukamel, D. and Mushlin, A. (1998). Quality of care information makes a difference: An analysis of market share and price changes after publication of the New York state cardiac surgery mortality reports. Medical Care 36(7), 945–954.

- Murphy, K. and Topel, R. (2006). The value of health and longevity. Journal of Political Economy 114(5), 871–903.

- Newhouse, J. (2002). Pricing the priceless: A health care conundrum. Cambridge MA: The MIT Press.

- Pauly, M. (1968). The economics of moral hazard: Comment. American Economic Review 58, 531–537.

- Rothschild, M. and Stiglitz, J. (1976). Equilibrium in competitive insurance markets: An essay on the economics of imperfect information. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 90(4), 629–649.

- Schneider, E. and Epstein, A. (1996). Influence of cardiac-surgery performance reports on referral practices and access to care – A survey of cardiovascular specialists. Journal of Health Economics 335, 251–256.

- Spence, A. M. (1980). Product selection, fixed cost, and monopolistic competition. Review of Economic Studies 43(2), 217–235.

- Steinbrook, R. (2006). Public report cards – Cardiac surgery and beyond. New England Journal of Medicine 255, 1847–1849.

- Zeckhauser, R. (1970). Medical insurance: A case study in the tradeoff between risk spreading and appropriate incentives. Journal of Economic Theory 2, 10–26.