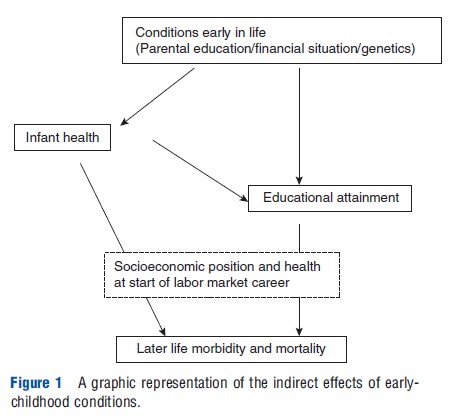

Indirect Effects: Causal Pathways From Early Childhood By Way Of Education To Later-Life Morbidity And Mortality

Figure 1 shows the main causal pathways that are considered. Note that compared to all the previous sections, the setting has been expanded: it is not restricted to the pathways that can be tracked down to the causes early in life, but also other possible determinants of later health are considered. The direct effect that links infant health to later-life morbidity and mortality is not discussed explicitly here (see Section Causal Effects of Early-Life Conditions).

Note that the methodological complications in the case of indirect effects are even larger than in the case of direct effects. In the former case, most studies typically restrict attention to just one of the arrows in the diagram, conditioning on the individual position at the starting point of the arrow. In general, this starting position can be endogenously affected by earlier events in the life of the individual or by unobserved determinants that also have a causal effect on the outcome.

The Effect Of Child Health On Educational Attainment

Quite a few studies in the development literature study the effect of child health or child nutrition on schooling outcomes. Ordinary least squares (OLS) estimates generally suggest a strong association between child health or nutrition and educational attainment. Several studies have tried to assess the causal effect of child health via Instrumental Variable approaches and sibling fixed-effect approaches. These studies seem to confirm the na¨ıve OLS estimates, but the size of the effect is generally larger. Miguel and Kremer (2004) used a randomized experiment to evaluate a program of a school-based treatment with a deworming drug in Kenya and found that absenteeism in treatment schools was substantially lower than in comparison schools, and that deworming increased schooling by approximately 1 month per pupil treated.

The literature for developed countries is small. Case et al. (2005) used British data from the Child Development Study to look at (among other things) the effect of childhood health on educational attainment. They found a strong association between childhood health and later educational attainment. It appears that the presence of chronic conditions in childhood has a stronger impact on educational attainment than does health at puberty. Their conclusion: the negative effect of bad health is cumulative in its effect on education. These results are based on observational data that follow a single cohort, which makes it difficult to make causal statements. Case and Paxson (2006) use adult height as a measure for childhood conditions and childhood health, and find that the height premium in adulthood (i.e., better labor market outcomes for taller people) can be explained by childhood scores on cognitive tests and by the fact that taller children selected into occupations that have higher cognitive skill requirements. Currie and Stabile (2003) examine the relationship between several common health disorders, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), depression, anxiety, and aggression, on future educational outcomes. They conclude that early-childhood mental health problems affect educational outcomes and that there is little evidence that income protects against the negative effects of mental health. A recent and innovative approach of Ding et al. (2006) focuses on a specific set of conditions (ADHD, depression, and obesity), and uses genetic markers that strongly predict these conditions as instruments. They find strong effects of these health conditions on student grade point averages. The larger part of this effect seems to be driven by the effect for females; for males they find no effect.

The Effect Of Education On Later Health And Mortality

Since Cutler and Lleras–Muney (2007) recently provided an excellent review of the literature on education and health, there is no need to fully review the papers discussed in their study, and can be drawn from their findings. Cutler and Lleras Muney performed some analyses of their own that confirm the strong association between education and (later-life) health. There is evidence for a causal effect of education on health. The most convincing evidence comes from studies that use changes in minimum schooling laws. This implies that one can make statements about the effect of additional schooling only regarding those who are at the bottom of the schooling distribution. Identifying which mechanisms generate these causal impacts remains speculative. The better educated have the better jobs and higher incomes, which may lead to better health and lower mortality rates at later ages. Case and Deaton (2003) find that people in manual occupations have worse self-reported health, and that there is a greater rate of health declines in these occupations. Their argument: much of the differences in health are driven by health-related absence from the labor force. Smith (2005) found that current and lagged financial measures of SES have no effect on future health, but that education does. This holds for older and for younger workers, thereby suggesting a potentially important role for factors such as the rank in the social distribution, the ability to process information and health behaviors.

The Whitehall studies of British civil servants show that morbidity and mortality fall with increases in social class. A low position in the social distribution leads to low control and high (job) demands, which in turn lead to stress, which puts workers at risk for cardiovascular disease. There is a strong relation between a measure for control and cardiovascular disease risk and this relationship also holds for non-civil servants. Cutler and Lleras–Muney (2007) argue that social position cannot be the main determinant of SES-related health differences. Life expectancy has increased in the developed world over the past three decades, although income inequality and crime have increased and social networks generally have become smaller. Also, some studies have shown that there are gradients in diseases that are not related to stress.

Schooling provides individuals with skills that help them acquire and process information, which helps them make better decisions. For example, consumer health information has been shown to increase the demand for medical services. More information increases the probability of care use, but conditional on care use, the quantity of care use is not related to information. Apparently, poorly informed consumers tend to underestimate the productivity of medical care in treating disease. However, differences in knowledge by SES create only modest differences in health behaviors by SES. Indeed, as noted by Cutler and Lleras–Muney (2007), although both educated and uneducated people today are well aware of the dangers involved with smoking, smoking is still more prevalent among the uneducated. Of interest is whether this association between smoking and schooling is causal, and if so, what mechanisms drive this effect. This can be addressed using Vietnam draft-avoidance behavior as an instrument for college attendance. The cohort of males born between 1945 and 1950 could avoid the Vietnam draft by enrolling into college, and this can be used as an instrument for college enrolment. The female cohort born between 1945 and 1950 can be used as a control group. It turns out that the level of education does causally affect smoking, and that those who initiated smoking are more likely to stop once they enter college. Peer effects or endogenous time preferences are likely to be important determinants. Improved information-processing capabilities due to increased schooling do not seem to be important. Subjective time discount rates are not related to smoking, but more general measures of time preferences and self-control, such as impulsivity and financial planning, are related to smoking.