Introduction

Mental illness is a common occurrence. Epidemiological evidence reveals that mental disorders are prevalent across more- and less-economically developed countries (WHO World Mental Health Consortium, 2004), and some mental health problems have been understood as being an illness since the time of Hippocrates. Mental disorders are known to have major consequences for longevity, quality of life, and productivity. For instance, the World Health Organization estimates that unipolar depressive disorders account for the third-largest share of lost disability-adjusted life years worldwide. There is a growing recognition that mental health disorders are also associated with reduced life expectancy. Recent estimates from the US suggest that 26% of nonelderly adults experienced a diagnosable mental disorder in the past 12 months (Kessler et al., 2005a). In the US, individuals with a mental health disorder die on average approximately 8 years younger than individuals with no mental health disorder, and 95% of these deaths were from internal causes (i.e., cardiovascular disease, cancer, pulmonary disease). Less than 5% of deaths were from external causes of suicide, homicide, or accidents, similar to the rate in the population reporting no mental health disorder.

A comprehensive multidisciplinary overview of the determinants of mental health, including genetic and other neurological bases for disease, is covered in the landmark Surgeon General’s report on mental health (US DHHS, 1999). Although the authors briefly review some of these concepts, their focus in this article is on the contributions of economists to this literature.

Mental illness includes a broad range of specific disorders, which are distinct from many physical health disorders in that there is no definitive diagnostic test for mental illness. Rather, mental illness is defined by the existence and severity of a set of symptoms that may include inappropriate anxiety, disturbances of thought and perception, dysregulation of mood, and cognitive dysfunction. The authors briefly review some of the more common and prominent examples of mental illness.

Anxiety disorders (including phobias, panic attacks, and generalized anxiety) are characterized by an individual’s anxiety responses to a given situation substantially exceeding what is emotionally and/or physiologically appropriate. Psychotic disorders (such as schizophrenia) involve serious disruptions of perception and thought process, which manifest in symptoms of hallucination, delusion, disorganized thoughts, flat affect, and inability to think abstractly. Mood disorders include depression, which is characterized by persistent symptom of sadness that is often associated with physical symptoms of insomnia, decreased appetite, and low-energy, and bipolar disorder, which is characterized by extreme fluctuation between depressed mood and elated mood. Impulse control disorders include attention-deficit and hyperactivity disorder, and are frequently associated with childhood and adolescence. Cognitive disorders affect the ability to organize, process, and recall information. Perhaps the most prominent example is Alzheimer’s disease which is progressive and generally is associated with aging (often more so than with broader mental illness).

There is an important difference between mental illnesses such as schizophrenia, where there is a clear binary categorization of having versus not having the disease; from other types of mental disorders such as depression, anxiety, or attention-deficit disorder, where the symptoms lie along a continuum from manageable and self-limiting to profoundly and persistently disabling. Analogous physical health conditions are, respectively, cancer, where there is a clear difference between people with and without the disease, and back pain, where many people experience symptoms, but only relatively few have their functioning disrupted by those symptoms. Nevertheless, all categories of mental disorders include conditions that range in severity, from relatively mild to profoundly severe.

Some view mental health status and happiness as lying along a common continuum. This article treats mental illness as a disease. This conceptual distinction is especially important in the context of studying economic issues in mental illness, as the idea of happiness is closely linked with the notion of utility that underlies classical consumer theory. This distinction is made clear by explicitly considering the idea of a mental health production function.

The pioneering work on health production functions (Grossman, 1972) was formulated from the perspective of physical health conditions but one needs to consider how it can be applied to mental health. Individuals are posited to have been born with an initial endowment of health capital. Health capital is a durable capital stock with two types of value: as a consumption good, where good health directly improves current utility, and an investment good, where health status affects other economic activity (such as employment). The stock of health capital at a point in time is determined by the stock of health capital at the previous point in time, health investments (including both behaviors and medical care), random shocks, and a depreciation term.

Physical health and mental health share some similarities in the context of this model, yet have some differences. Similar to the case of physical health, there is evidence of heterogeneity in initial endowment of mental health. For example, economists are beginning to contribute to an existing body of psychology and neuroscience research on the effects of stress in utero. Research finds that stressful conditions during pregnancy (particularly the first trimester) lead to significant increases in subsequent mental health problems. One study finds that maternal stress during pregnancy doubles the risk of schizophrenia in offspring (Malaspina et al., 2008). In addition, similar to physical health, a range of treatment technologies exist which can improve mental health status between time periods.

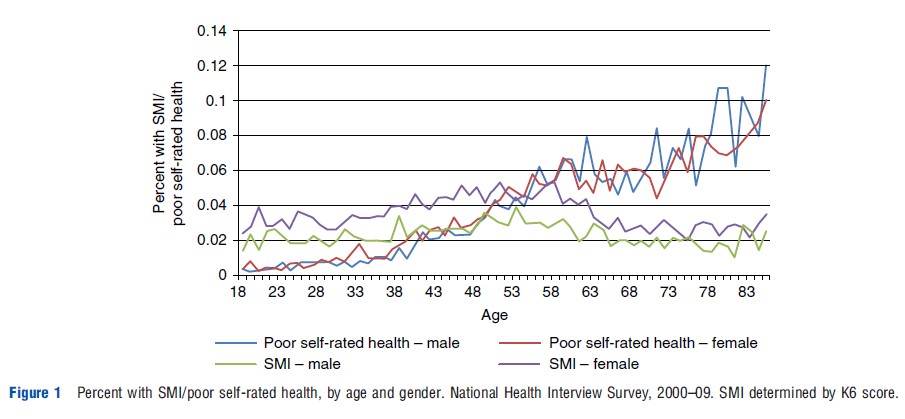

Nevertheless, mental health contrasts in some important ways from physical health in the context of this model. The notion of intertemporal depreciation does not fit neatly with mental health. The Grossman model assumes that health depreciates at an increasing rate with age. This assumption fits the data fairly well for the case of physical health, as illustrated in Figure 1 (measured here as the proportion of the population reporting poor self-rated health). However, mental health (measured here as the proportion of the population with severe mental distress) exhibits a relatively flat, inverse U-shaped pattern in age, consistent with epidemiological studies that find that most mental illnesses first occur early in life. On average mental health depreciates only moderately until the mid-50s, and then improves moderately at older ages.

Another way that mental health departs from the classic health capital model is in the type of health investment inputs. Similar to general health, health care can affect mental health in ways that are broadly similar to physical health with many evidence-based treatments available. For example, pharmaceutical treatments can improve symptoms of anxiety, major depression, and schizophrenia as well as other mental health disorders. Brief psychotherapy is also effective in treating acute cases, as well as extending periods of remission. Also, like general health conditions, health behaviors (e.g., exercise) can affect mental health. Yet, it is believed that psychosocial stress plays a relatively larger role in the production of mental health than of physical health. Psychosocial stress has been studied extensively by research in psychology and sociology, and a review of this literature is outside of the scope of this article. But in brief, these fields have produced striking evidence on the effects of psychosocial stress on mental disorders, and have identified moderators and mediators of this relationship. More recently, some sources of psychosocial stress have been studied by economists, as described below in section Employment.

Finally, it is noteworthy that any economic model of health status that is derived from classical consumer theory is faced with the challenge that in many cases, mental illness represents a break from ‘rational’ behavior. Indeed, the departure from an individual’s normal capacity for decision making (e.g., the compromised perception and thought processing that are common in psychosis) and changes to an individual’s preference (e.g., not caring about the future is a symptom of major depressive disorder and can be interpreted by an economist as a change to one’s discount rate) are hallmarks of mental illness and can violate the axioms of expected utility theory.

Economists have focused most of their interest on three specific (related) determinants of mental health: income, labor market participation, and macroeconomic conditions. In the rest of this article the authors discuss findings related to these inputs. Like other health disorders, although risk factors have been documented, much of the heterogeneity in mental health disorders and outcomes remains unexplained.

Income

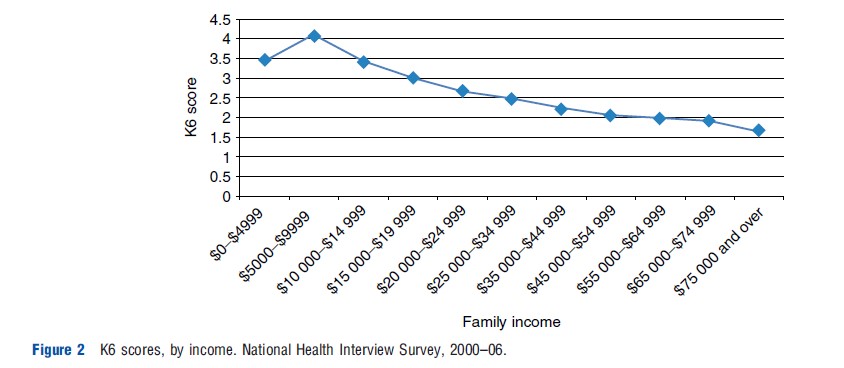

Disentangling the effects of income on mental health from the reverse effect is difficult because mental health disorders, like other health conditions, are also likely to have a direct effect on income through labor market outcomes, and perhaps household formation. Figure 2 uses data from the National Health Interview Survey to examine the correlation between mental health (measured by K6 score) and household income in the US. This figure illustrates the strong correlation between income and mental health. However, epidemiological evidence suggests that although the within country correlation between income and mental health is strong, there is a weaker correlation between income and mental health across countries and some evidence suggests a higher prevalence of mental disorders in higher-income countries. Evidence from quasinatural experiments and randomized experiments suggests a causal relationship with income having a direct effect on mental health. Evans and Garthwaite (2010) examine the effects of the US Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) expansions on maternal mental health. Comparing low-income mothers with two children, who received substantially more in benefits, with mothers with one child, they find that mothers with two children had significantly fewer days with poor mental health over the previous 30 days. In Canada, Milligan and Stabile (2011) find strong evidence that additional income through child benefits has significant positive effects on maternal mental health and children’s mental health. Although these studies suggest an effect, one cannot necessarily extrapolate these findings to other populations, including populations with higher incomes.

Case (2004) finds that members of South African households that include a pensioner are less depressed than members of other households, again suggesting a causal effect of income on mental health. Fernald et al. (2008) find that the effect of giving loans to previously rejected applicants reduced depressive symptoms in men, despite increased perceived stress.

Economic theory has also been applied to suicide, leading to the prediction that as with mental health in general, suicide will decrease with permanent income (Hammermesh and Soss, 1974) and population-level data on suicide rates are generally consistent with that prediction. Recent work suggests that relative income may affect suicide risk. For example, Daly et al. (2012) finds that, holding own income constant, a 10% increase in county income was associated with a 4.5% increase in suicide hazard, suggesting that lower social status increases suicide risk.

Macroeconomic Conditions

A consistent finding from the economic literature on macroeconomic effects on health is that physical health is countercyclical, which is commonly explained by individuals investing greater time in physical-health promoting activities when the opportunity costs of time are lower. Interestingly, the relationship between macroeconomic conditions and mental health appears to be procyclical. The research literature uses unemployment rates (measured at various level of aggregation) as a measure of local macroeconomic conditions. In periods of higher unemployment levels of suicides, various measures of mental distress, and other disabling mental disorders increase, even though measures of physical health (i.e., acute health conditions and disability) improve. For example, Ruhm (2003) finds that a 1% increase in unemployment was associated with a 7.3% decline in nonpsychotic mental disorders. Economists find that Google searches for mental health-related terms increase with unemployment rates, providing further, novel evidence of the procyclicality of mental health. Less is known about how and why macroeconomic conditions affect mental health. Three nonmutually exclusive hypotheses are that poor macroeconomic conditions reduce individuals’ mental health by reducing income, by increasing rates of job loss, and by increasing overall levels of psychosocial stress.

Employment

The direct and indirect effects of unemployment on mental health have been compared with large and significant direct effects found. Although the direct effects of unemployment are much greater than indirect effects, when measuring the consequences of unemployment at a population level, Helliwell and Huang (2011) find that the indirect effects dominate because a much larger population is affected. This work suggests the nonpecuniary effects of being unemployed on mental health are 5.5 times greater than the effects due to loss of income. They also find that higher unemployment benefits (as measured by the benefits replacement rate) do not mitigate the effect of unemployment on mental health. On the other hand, Salm (2009) examines exogenous involuntary job loss, as measured by business closures, and finds little evidence of an effect of job loss on the mental health outcomes studied.

Others have looked specifically at the effect of retirement on mental health outcomes. Dave et al. (2008) find significant negative effects of retirement on mental health. Again, they find that income is not the dominant mechanism by which retirement affects mental health. They explore the mechanisms for this effect and find evidence for the importance of declines in social interactions and physical activity.

Can public programs alleviate life events that affect mental health? Economic studies have failed to find significant effects of declining US welfare caseloads on maternal mental health; though there is some evidence that length of maternity leave may affect the severity of depression. Kling et al. (2007) examined the effect of being offered housing vouchers on health. They find being randomly assigned to receive a housing voucher did lead to lower poverty rates and residence in safer neighborhoods 4–7 years postrandom assignment. Although no significant effects were found on adult physical health outcomes, large positive effects on adult mental health outcomes were found, with a 45% reduction in relative risk of serious mental illness.

The existing literature on determinants of mental health finds that psychosocial stress negatively affects mental health, and that important psychosocial stressors can emerge from individual and societal economic conditions. Experimental research, including animal studies, identifies the causal effect of psychosocial stress on mental health in controlled laboratory settings. Observational research links individual and societal economic conditions to levels of stress, and correlates stress with mental health without identifying a causal effect of stress, per se. Economists have recently bridged the gap between these two broad areas of research by applying the tools of empirical microeconomics to the study of mental health outcomes. This economic research generally suggests that individual and societal economic conditions do affect mental health, in some cases substantially. Yet, few evaluations of policies to affect economic conditions consider these effects when evaluating the costs and benefits of programs. Generally, existing literature suggests including mental health as an outcome measure in these evaluations is likely to increase the benefits of these policies.

Bibliography:

- Case, A. (2004). Does money protect health status? Evidence from South African pensions, NBER Chapters. In Wise, D. A. (ed.) Perspectives on the economics of aging, pp. 287–312. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Daly, M., Wilson, D. J. and Johnson, N. J. (2012). Relative status and well-being: Evidence from US suicide deaths. Review of Economics and Statistics. Available at: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1026351 (accessed 23.08.13).

- Dave, D., Rashad, I. and Spasojevic, J. (2008). The effects of retirement on physical and mental health outcomes. Southern Economic Journal 75(2), 497–523.

- Evans W. N. and Garthwaite C. L. (2010). Giving mom a break: The impact of higher EITC payments on maternal health. NBER Working Paper 16296. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Fernald, L., Hamad, R., Karlan, D., Ozer, E. J. and Zinman, J. (2008). Small individual loans and mental health: A randomized controlled trial among South African adults. BMC Public Health 8(16), 409.

- Grossman, M. (1972). On the concept of health capital and the demand for health. The Journal of Political Economy 80(2), 223–255.

- Hammermesh, D. S. and Soss, N. M. (1974). An economic theory of suicide. Journal of Political Economy 82(1), 83–98.

- Helliwell J. F.and Huang H. (2011). New measures of the costs of unemployment: Evidence from the Subjective Well-Being of 2.3 Million Americans. NBER Working Paper 16829. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., et al. (2005a). Lifetime prevalence and age- of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62, 593–602.

- Kling, J., Liebman, J. and Katz, L. (2007). Experimental analysis of neighborhood effects. Econometrica 75(1), 83–119.

- Malaspina, D., Corcoran, C., Kleinhaus, K. R., et al. (2008). Acute maternal stress in pregnancy and schizophrenia in offspring: A cohort prospective study. BMC Psychiatry 8, 71.

- Milligan, K. and Stabile, M. (2011). Do child tax benefits affect the wellbeing of children? Evidence from Canadian child benefit expansions. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 3(3), 175–205.

- Ruhm, C. (2003). Good times make you sick. Journal of Health Economics 22(4), 637–658.

- Salm, M. (2009). Does job loss cause ill health? Health Economics 18(9), 1075–1089.

- US Department of Health and Human Services (1999). Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health.

- WHO World Mental Health Survey Consortium (2004). Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Journal of the American Medical Association 291(21), 2581–2590.

- Chatterji, P. and Markowitz, S. (2005). Does the length of maternity leave affect maternal health? Southern Economic Journal 72(1), 16–41.

- Kaestner, R. and Tarlov, E. (2006). Changes in the welfare caseload and the health of low-educated mothers. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 25(3), 623–641.

- Kerwin, D. and DeCicca, P. (2008). Local labour market fluctuations and health: Is there a connection and for whom? Journal of Health Economics 27(6), 1332–1350.

- Kessler, R. C., Chiu, W. T., Demler, O. and Walters, E. E. (2005). Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National comorbidity survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62(6), 617–627.

- Ruhm, C. (2000). Are recessions good for your health? Quarterly Journal of Economics 115(2), 617–650.

- World Health Organization (2008). The global burden of disease. Geneva: WHO Press. 2004 Update.